Mauritania Tingitana

| Provincia Mauretania Tingitana | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of the Roman Empire | |||||||||||||

| 42 AD–Early 8th century | |||||||||||||

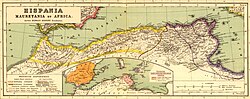

The province of Mauretania Tingitana within the Roman Empire, c. 125 AD | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Tingis, Septem | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical Antiquity, Late Antiquity | ||||||||||||

• Incorporated into the Roman Empire as a full province | 42 AD | ||||||||||||

• Vandal Conquest | 430s AD | ||||||||||||

• Byzantine partial reconquest by Vandalic War | 534 AD | ||||||||||||

| Early 8th century | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Morocco Spain: Ceuta Melilla Plazas de soberanía | ||||||||||||

| History of Morocco |

|---|

|

Mauretania Tingitana (Latin for "Tangerine Mauretania") was a Roman province, coinciding roughly with the northern part of present-day Morocco.[1][2] The territory stretched from the northern peninsula opposite Gibraltar, to Sala Colonia (or Chellah) and Volubilis to the south,[3] and as far east as the Mulucha (or Malva) river. Its capital city was Tingis, which is the modern Tangier. Other major cities of the province were Iulia Valentia Banasa, Septem, Rusadir, Lixus and Tamuda.[4]

History

After the death in 40 AD of Ptolemy of Mauretania, the last Ptolemaic ruler of the Kingdom of Mauretania, in about 44 AD Roman Emperor Claudius annexed the kingdom to the Roman Empire and partitioned it into two Roman provinces: Mauretania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis.[1] The Mulucha (Moulouya River), located around 60 km west of modern Oran, Algeria, became the border separating them.[1][5]

The Roman occupation did not extend very far into the continent. In the far west, the southern limit of imperial rule was Volubilis, which was ringed with military camps such as Tocolosida slightly to the south east and Ain Chkour to the north-west, and a fossatum or defensive ditch, or commonly known as a trench. On the Atlantic coast Sala Colonia was protected by another ditch and a rampart and a line of watchtowers.

This was not a continuous line of fortifications: there is no evidence of a defensive wall like the one that protected the turbulent frontier in Britain at the other extremity of the Roman Empire. Rather, it was a network of forts and ditches that seems to have functioned as a filter. The limes – the word from which the English word “limit” is derived – protected the areas that were under direct Roman control by funnelling contacts with the interior through the major settlements, regulating the links between the nomads and transhumants with the towns and farms of the occupied areas.

The same people lived on both sides of these limes, although the population was quite small. Volubilis had perhaps twenty thousand inhabitants at most in the second century. On the evidence of inscriptions, only around ten to twenty per cent of them were of European origin, mainly Spanish; the rest were local.

Roman historians (like Ptolemy) considered all of Morocco north of the Atlas Mountains part of the Roman Empire, because in the times of Augustus, Mauretania was a vassal state and its rulers (like Juba II) controlled all the areas south of Volubilis. The effective control of Roman legionaries, however, was up to the area of Sala Colonia (the castra "Exploratio Ad Mercurios", south of Sala Colonia, is the southernmost Roman settlement discovered until now). Some historians, like Leo Africanus, believe the Roman frontier reached the area of Casablanca, founded by the Romans as a port named "Anfa". Indeed, the modern city of Azemmour in central Morocco lies on the ancient Azama, a trading port of Phoenician and later Roman origins. Still today can be seen the remains of a Roman deposit for grain in the so-called "Portuguese cisterns".[6]

Pliny the Elder described in some detail the area south of the Atlas Mountains, when Gaius Suetonius Paulinus undertook a military expedition in 41:

Suetonius Paulinus, whom we have seen Consul in our own time, was the first Roman general who advanced a distance of some miles beyond Mount Atlas. He has given us the same information as we have received from other sources with reference to the extraordinary height of this mountain, and at the same time he has stated that all the lower parts about the foot of it are covered with dense and lofty forests composed of trees of species hitherto unknown. The height of these trees, he says, is remarkable; the trunks are without knots, and of a smooth and glossy surface; the foliage is like that of the cypress, and besides sending forth a powerful odour, they are covered with a flossy down, from which, by the aid of art, a fine cloth might easily be manufactured, similar to the textures made from the produce of the silk-worm. He informs us that the summit of this mountain is covered with snow even in summer, and says that having arrived there after a march of ten days, he proceeded some distance beyond it as far as a river which bears the name of Ger (a northern affluent of the Niger river?); the road being through deserts covered with a black sand, from which rocks that bore the appearance of having been exposed to the action of fire, projected every here and there; localities rendered quite uninhabitable by the intensity of the heat, as he himself experienced, although it was in the winter season that he visited them.[7]

Roman province

During the reign of the Numidian King Juba II, Emperor Augustus had already founded three colonias (with Roman citizens) in Mauretania close to the Atlantic coast: Iulia Constantia Zilil, Iulia Valentia Banasa and Iulia Campestris Babba.

This western part of Mauretania was to become the province called Mauretania Tingitana shortly afterwards. The region remained a part of the Roman Empire until 429, when the Vandals overran the area and Roman administrative presence came to an end.

The most important city of Mauretania Tingitana was Volubilis. This city was the administrative and economic center of the province in western Roman Africa. The fertile lands of the province produced many commodities such as grain and olive oil, which were exported to Rome, contributing to the province's wealth and prosperity. Archaeology has documented the presence of a Jewish community in the Roman period.[8]

The principal exports from Mauretania Tingitana were purple dyes and valuable timber. Tingitana also supplied Rome with agricultural goods and animals, such as lions and leopards. The native Mauri were highly regarded and recruited by the Romans as soldiers, especially as light cavalry. Clementius Valerius Marcellinus is recorded as the governor (praeses) between 24 October 277 and 13 April 280.[9]

According to tradition, the martyrdom of St Marcellus took place on 28 July 298 at Tingis (Tangier). During the Tetrarchy (Emperor Diocletian's reform of Roman governmental structures in 297), Mauretania Tingitana became part of the Diocese of Hispaniae, 'the Spains', and, by extension, part of the Praetorian prefecture of Gaul, thus it was across the sea from the European territory of Diocese and Prefecture it belonged to. Mauretania Caesariensis was in the Diocese of Africa. Lucilius Constantius is recorded as governor (praeses) in the late fourth century.

The Notitia Dignitatum shows also, in its military organisation, a Comes Tingitaniae with a field army composed of two legions, three vexillations, and two auxilia palatina. Flavius Memorius held this office (comes) at some point during the middle of the fourth century. However, it is implicit in the source material that there was a single military command for both of the Mauretanian provinces, with a Dux Mauretaniae (a lower rank) controlling seven cohorts and one ala.

The Germanic Vandals established themselves in the province of Baetica in 422 AD under their king, Gunderic, and, from there, they carried out raids on Mauretania Tingitana. In 427 AD, the Comes Africae, Bonifacius, rejected an order of recall from the Emperor Valentinian III, and he defeated an army sent against him. He was less fortunate when a second force was sent in 428 AD. In that year, Gunderic was succeeded by Gaiseric, and Bonifacius invited Gaiseric into Africa, providing a fleet to enable the passage of the Vandals to Tingis and Septem (Ceuta). Bonifacius intended to confine the Vandals to Mauretania, but, once they had crossed the straits, they rejected any control and marched on Carthage.

Byzantines

In 533 AD, the Byzantine general Belisarius reconquered the former Diocese of Africa from the Vandals on behalf of the Emperor Justinian I. All the territory west of Caesarea had already been lost by the Vandals to the Berber "Mauri", but a re-established Dux Mauretaniae kept a military unit at Septem (modern Ceuta). This was the last Byzantine outpost in Mauretania Tingitana; the rest of what had been the Roman province was united with the Byzantine part of Andalusia under the name of the Praetorian prefecture of Africa, with Septem as administrative capital.

Most of the Maghreb littoral was later organised as the Exarchate of Africa, a special status in view of the outpost defense needs.

There was also an indigenous principality in Tingitana which existed in the 6th and 7th centuries, attested for by inscriptions at Volubilis and the Mausoleum at Souk El Gour.[10]

When the Umayyad Caliphate conquered all of Northern Africa, it brought Islam to the local adherents of the traditional Berber religion and Christianity. The two Mauretania provinces were consolidated as the territory of al-Maghrib (Arabic for 'the West', and still the official name of the Sharifian Kingdom of Morocco). This larger province also included over half of modern Algeria.

Stone ruins dating from the Roman era exist at various archaeological sites, including the Capitoline Temple at Volubilis, the palace of Gordius, Sala Colonia, Tingis and Iulia Constantia Zilil.

See also

- List of Roman governors of Mauretania Tingitana

- Mauretania Sitifensis

- Mauretania Caesariensis

- Roman roads in Morocco

- Tabula Banasitana

References

- ^ a b c Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 908.

- ^ Sigman, Marlene C. (1977). "The Romans and the Indigenous Tribes of Mauritania Tingitana". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 26 (4): 415–439. ISSN 0018-2311.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan, Chellah, The Megalithic Portal, ed. Andy Burnham

- ^ University of Granada: Mauretania Tingitana (in Spanish)

- ^ Richard J.A. Talberts, Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World - p. 457

- ^ Roman Azama

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History 5.1

- ^ Two Thousand Years of Jewish Life in Morocco, Haim Zafrani, Ktav, 2005, p. 2

- ^ J.E.H. Spaul, "Governors of Tingitana", Antiquités africaines 30 (1994), p. 253

- ^ Mahjoubi, Ammar; Salama, Pierre (1981). "The Roman and post-Roman period in North Africa". General History of Africa: Volume 2. UNESCO Publishing. p. 508. Archived from the original on 2023-04-06. Retrieved 2024-02-21.

Further reading

- J. B. Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire (online)

- Fentress, "Tribe and faction: the case of the Gaetuli", MEFRA, 94 (1982), pp. 325-34.

- A. H. M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire, Blackwell, Oxford 1964. ISBN 0-631-15076-5

- Mugnai, N. (2018). Architectural Decoration and Urban History in Mauretania Tingitana. Quasar. ISBN 978-88-7140-853-8.

- Pauly-Wissowa (in German).

- M. C. Sigman, "The Romans and the indigenous tribes of Mauretania Tingitana", Historia, 26 (1977), pp. 415-439.

- Westermann, Großer Atlass zur Weltgeschichte (in German).