Minbar of the Kutubiyya Mosque

The Minbar of the Kutubiyya Mosque is a minbar (Arabic: منبر; a mosque furnishing similar to a pulpit) produced in Cordoba, Spain (al-Andalus at the time), in the early 12th century by order of the Almoravid amir Ali ibn Yusuf. The minbar was commissioned for the main mosque of Marrakesh, the Almoravid capital in Morocco. After the Almohad conquest of Marrakesh in 1147, the minbar was moved to the new Kutubiyya Mosque built by Abd al-Mu'min. It remained there until 1962, when it was moved into storage and then to the El Badi Palace for public display, where it remains today. Made primarily of wood and decorated with a variety of techniques, the minbar is considered one of the high points of Moorish, Moroccan, and Islamic art.[1][2][3][4] It was enormously influential in the design of subsequent minbars produced across Morocco and the surrounding region.[1][3]

History

The Kutubiyya Mosque's historic minbar (pulpit) was commissioned by Ali ibn Yusuf, one of the last Almoravid rulers, and created by a workshop in Cordoba, Spain (al-Andalus).[1][5] Prior to this, one of the most celebrated minbars in the region was the minbar of the Great Mosque of Cordoba, commissioned by Caliph al-Hakam II during his expansion of the mosque between 961 and 976. Like the later Almoravid-commissioned minbar, it was made using precious woods and inlaid with ivory, but it has not survived to the present day.[6] The Kutubiyya minbar is thus one of the only historical artifacts which gives us an idea of what this Cordoban craftsmanship may have looked like.[6][1]

The production of Ali ibn Yusuf's minbar started in 1137 and is estimated to have taken seven years.[4]: 302 The minbar was shipped in pieces from Cordoba and reassembled in Marrakesh.[1] It is believed that the minbar was originally placed in the grand mosque of the Almoravid city, the first Ben Youssef Mosque (named after Ali ibn Yusuf, but entirely rebuilt in later centuries).[1]

In 1147 the Almohad ruler Abd al-Mu'min conquered Marrakesh from the Almoravids and began construction of the Kutubiyya Mosque that same year.[7][8] This new mosque was to replace the Ben Youssef Mosque as the main mosque of the city, as Abd al-Mu'min is reported to have demolished all the mosques in the city built under the Almoravids, purportedly due to their erroneous qibla alignment.[4] It is not certain when the mosque was completed, but it may have been around 1157.[8][9] Abd al-Mu'min ordered the Almoravid minbar of Ali ibn Yusuf to be transferred to his new mosque, possibly an indication of the high esteem in which the minbar was already held at the time.[4] A hidden specially designed mechanism integrated into the new mosque allowed for the minbar to advance and retract, seemingly on its own, from its storage room next to the mihrab; a feature at which contemporary observers marvelled.[1]

For reasons which are no longer well understood, Abd al-Mu'min decided to rebuild a second Kutubiyya Mosque right next to the first and nearly identical to it. The minbar was then moved to this second mosque while the first mosque was abandoned and eventually demolished.[7] The minbar remained in use here until 1962, when it was moved into storage for protection.[5][10][11] By then its wooden structure and decoration had deteriorated significantly from centuries of use.[1] In 1996-97 the minbar was partially restored by an international team of experts from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Ministry of Cultural Affairs of the Kingdom of Morocco.[1] The minbar was then moved to a room in the El Badi Palace in Marrakesh for public display, where it remains today.[1][5]

Design and decoration

The minbar is essentially a triangular structure with the hypotenuse side occupied by a staircase with nine steps.[2] It is 3.46 metres (11.4 ft) long, 0.87 metres (2 ft 10 in) wide, and 3.86 metres (12.7 ft) tall.[11][1] The main structure is made in North African cedar wood, although the steps were made of walnut tree wood and the minbar's base was made with fir tree wood.[1] The surfaces are decorated through a mix of marquetry and inlaid sculpted pieces.

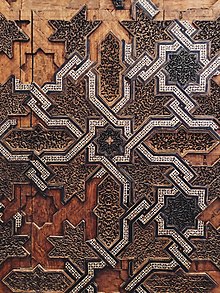

The large triangular faces of the minbar on either side are covered in an elaborate and creative motif centered around eight-pointed stars, from which decorative bands inlaid with bone and coloured woods then interweave and repeat the same pattern across the rest of the surface.[1] The spaces between these bands form other geometric shapes which are filled with panels of deeply carved arabesques. These panels are made from different coloured woods including boxwood (for lighter shades), jujube (originally of reddish colour), and, for the central star-shaped panels, dark acacia wood (previously assumed to be ebony but identified by recent closer studies as African blackwood).[1] There is a 6 centimetres (2.4 in) wide band of Qur'anic inscriptions in Kufic Arabic script on blackwood and bone running along the top edge of the balustrades.[1]

The other surfaces of the minbar feature a variety of different motifs. The steps of the minbar are decorated with images of an arcade of Moorish (horseshoe) arches inside which are curving plant motifs, all made entirely in marquetry with different colored woods.[1] The inside of the staircase's balustrades were originally covered in panels of carved arabesques, but only one of these has survived.[1] The bottom of the minbar's staircase is flanked by two much taller balustrades pierced with a horseshoe-arch frame. Its surfaces are covered with more highly elaborate ornamentation including carvings and bands of fine wooden mosaics, forming somewhat different motifs from the rest of the minbar. The outer sides of these balustrades feature curved interlacing bands around quatrefoil and dodecagonal forms, while the inner sides feature an eight-pointed star composition (an abridged version of the pattern on the main flanks of the minbar) which is framed by a band of blackwood deeply carved with a Qur'anic inscription of Kufic Arabic letters on an arabesque background.[1] The top of the staircase is framed by similar but much shorter balustrades pierced with horseshoe arches. These in turn have their own set of curving motifs, mosaics, and arabesque panel decoration.[1]

The backrest at the top of the minbar was probably one of the most lavishly decorated parts of it but unfortunately it has lost most of this surface decoration, with only outlines and fragments still visible.[1] Another Kufic inscription, smaller and simpler than the ones found around the sides of the minbar, is carved around the top edge of the backrest but is now incomplete. It states that the minbar was fabricated in Cordoba for a "great venerated mosque" (probably the Mosque of Ali ibn Yusuf in Marrakesh).[1]

Mechanism moving the minbar in the Kutubiyya Mosque

Historical accounts describe a mysterious and invisible semi-automated mechanism in the Kutubiyya Mosque by which the minbar would emerge, seemingly on its own, from its storage chamber next to the mihrab and move forward into position for the imam's sermon.[1][7]: 176–177 Likewise, the maqsura of the mosque (a wooden screen that separated the caliph and his entourage from the general public during prayers) was also retractable in the same manner and would emerge from the ground when the caliph attended prayers at the mosque, and then retract once he left.[1] This mechanism, which elicited great curiosity and wonder from contemporary observers, was designed by an engineer from Malaga named Hajj al-Ya'ish, who also completed other projects for the caliph.[7][4]: 314 Modern archaeological excavations carried out on the first Kutubiyya Mosque have found evidence confirming the existence of such a mechanism under the floor of the mosque, though its exact workings are not fully established. One theory, which appears plausible from the physical evidence, is that it was powered by a hidden system of pulleys and counterweights.[1][12]

Legacy and influence

The minbar was already widely praised and appreciated among observers and scholars soon after its creation.[2] The fact that the Almohad leader Abd al-Mu'min, who is reputed to have destroyed all Almoravid religious buildings in Marrakesh after he took the city, selected the minbar to be transferred and used at his newly built great mosque (the Kutubiyya) suggests that he saw it as a trophy and a significant artistic object in its own right.[2][1]

The minbar's artistic style and quality was hugely influential and set a standard which was repeatedly imitated, but never surpassed, in subsequent minbars across Morocco and parts of Algeria.[1] The only other minbar produced in the same period and considered to be of similar quality is the Almoravid minbar of the Qarawiyyin Mosque in Fes, produced in 1144.[2][3] The Almohad minbar of the Kasbah Mosque in Marrakesh, produced in 1189-1195, marks another high mark of minbar artistry which presented a slight variation on the same model and also proved influential in subsequent designs.[7][1][13][14] Later minbars are seen by scholars as lesser imitations of these earlier models, though still in some cases accomplished works of art in their own right.[1] Notable examples include the Almohad renovation to the minbar of the Andalusi Mosque in Fes (1203-1209),[1] the Marinid minbar of the Great Mosque of Taza (circa 1290-1300),[1] the Marinid minbar of the Bou Inania Madrasa (1350-1355),[1][13]: 481 and the Saadian minbar of the Mouassine Mosque (1562-1573).[1][14]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Bloom, Jonathan; Toufiq, Ahmed; Carboni, Stefano; Soultanian, Jack; Wilmering, Antoine M.; Minor, Mark D.; Zawacki, Andrew; Hbibi, El Mostafa (1998). The Minbar from the Kutubiyya Mosque. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Ediciones El Viso, S.A., Madrid; Ministère des Affaires Culturelles, Royaume du Maroc.

- ^ a b c d e Dodds, Jerrilynn D., ed. (1992). Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 362–367. ISBN 0870996371.

- ^ a b c Terrasse, Henri (1957). "Minbars anciens du Maroc". Mélanges d'histoire et d'archéologies de l'occident musulman: Tome II: Hommage à Georges Marçais. Imprimerie Officielle du Gouvernment Général de l'Algérie. pp. 159–167.

- ^ a b c d e Bennison, Amira K. (2016). The Almoravid and Almohad Empires. Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ a b c Kimmelman, Michael (1998-08-25). "From Mosque To Museum; Restoring an Object's Surface May Petrify Its Heart". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-10-16.

- ^ a b M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Minbar". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b c d e Deverdun, Gaston (1959). Marrakech: Des origines à 1912. Rabat: Éditions Techniques Nord-Africaines.

- ^ a b Wilbaux, Quentin (2001). La médina de Marrakech: Formation des espaces urbains d'une ancienne capitale du Maroc. Paris: L'Harmattan. ISBN 2747523888.

- ^ Salmon, Xavier (2018). Maroc Almoravide et Almohade: Architecture et décors au temps des conquérants, 1055-1269. Paris: LienArt.

- ^ "Jami' al-Kutubiyya". ArchNet. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ a b El Khatib-Boujibar, Naima. "Minbar". Discover Islamic Art, Museum With No Frontiers. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ Parker, Richard (1981). A practical guide to Islamic Monuments in Morocco. Charlottesville, VA: The Baraka Press.

- ^ a b Lintz, Yannick; Déléry, Claire; Tuil Leonetti, Bulle (2014). Maroc médiéval: Un empire de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. Paris: Louvre éditions. ISBN 9782350314907.

- ^ a b Salmon, Xavier (2016). Marrakech: Splendeurs saadiennes: 1550-1650. Paris: LienArt. ISBN 9782359061826.

External links

- Full copy of The Minbar from the Kutubiyya Mosque, published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Includes extensive analysis and detailed images.