Missions Etrangères de Paris

Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris[1] | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Post-nominal letters: MEP[1] |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1658 |

| Founder | Bishop François Pallu, MEP[2] |

| Type | Society of Apostolic Life of Pontifical Right (for Men) |

| Headquarters | 128 Rue du Bac, 75007, Paris, France[1] |

| Membership | 189 members (178 priests) as of 2018[3] |

Superior General | Vincent Sénéchal[3] |

| Affiliations | Catholic Church |

| Website | missionsetrangeres |

The Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (French: Société des Missions Etrangères de Paris, pronounced [sɔsjete de misjɔ̃ etʁɑ̃ʒɛʁ də paʁi], MEP) is a Catholic missionary organization. It is not a religious institute, but an organization of secular priests and lay persons dedicated to missionary work in foreign lands.[4]

The Society of Foreign Missions of Paris was established 1658–63. In 1659, instructions for establishment of the Paris Foreign Missions Society were given by Rome's Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. This marked the creation of a missionary institution that, for the first time, did not depend on the control of the traditional missionary and colonial powers of Spain or Portugal.[5] In the 350 years since its foundation, the institution has sent more than 4,200 missionary priests to Asia and North America. Their mission is to adapt to local customs and languages, develop a native clergy, and keep close contacts with Rome.[6]

In the 19th century, local persecutions of missionary priests of the Paris Foreign Missions Society were often a pretext for French military intervention in Asia.[7] In Vietnam, such persecutions were used by the French government to justify the armed interventions of Jean-Baptiste Cécille and Charles Rigault de Genouilly. In China, the murder of the priest Auguste Chapdelaine became the casus belli for the French involvement in the Second Opium War in 1856. In Korea, persecutions were used to justify the 1866 French campaign against Korea.

Today, the Paris Foreign Missions Society remains an active institution in the evangelization of Asia.

Background

The traditional colonial powers of Spain and Portugal had initially received from the Pope an exclusive agreement to evangelize conquered lands, a system known as Padroado Real in Portuguese and Patronato real in Spanish. After some time however, Rome grew dissatisfied with the Padroado system, due to its limited means, strong involvement with politics, and dependence on the kings of Spain and Portugal for any decision.[8]

From a territorial standpoint also, Portugal had been losing ground against the new colonial powers of England and the Dutch Republic, meaning that it was becoming less capable of evangelizing new territories.[9] In territories that it used to control, Portugal had seen some disasters; for instance, Japanese Christianity was eradicated from around 1620.[10]

Finally, Catholic officials had doubts about the efficacy of religious orders, such as the Dominicans, Franciscans, Jesuits or Barnabites, since they were highly vulnerable in case of persecutions. They did not seem able to develop local clergy, who would be less vulnerable to state persecution. Sending bishops to develop a strong local clergy seemed to be the solution to achieve future expansion:[10]

"We have all reason to fear that what happened to the Church of Japan could also happen to the Church of Annam, because these kings, in Tonkin as well as in Cochinchina, are very powerful and accustomed to war... It is necessary that the Holy See, by its own movement, give pastors to these Oriental regions where Christians multiply in a marvellous way, lest, without bishops, these men die without sacrament and manifestly risk damnation." Alexandre de Rhodes.[10]

As early as 1622, Pope Gregory XV, wishing to take back control of the missionary efforts, had established the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Congregatio de Propaganda Fide, commonly known as Propaganda) with the objective of bringing non-Catholic Christians to the Catholic faith, and also inhabitants of the American continent and Asia.[8] In order to do so, Rome resurrected the system of Apostolic vicars, who would report directly to Rome in their missionary efforts, and would be responsible to create a native clergy.[11]

In the field, violent conflicts would erupt between the Padroado and the Propaganda during the 17th and 18th centuries.[8] (When the first missionaries of the Paris Foreign Missions Society were sent to the Far East, the Portuguese missionaries were ordered to capture them and send them to Lisbon).[12] The creation of the Paris Foreign Missions Society was well-aligned with Rome's efforts to develop the role of the Propaganda.[13]

Establishment

The creation of the Paris Foreign Missions Society was initiated when the Jesuit priest Alexandre de Rhodes, back from Vietnam and asking for the dispatch of numerous missionaries to the Far East, obtained in 1650 an agreement by Pope Innocent X to send secular priests and bishops as missionaries.[14] Alexandre de Rhodes received in Paris in 1653 a strong financial and organizational support from the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement for the establishment of the Paris Foreign Missions Society.[15][16] Alexander de Rhodes found secular clergy volunteers in Paris in the persons of François Pallu and Pierre Lambert de la Motte and later Ignace Cotolendi, the first members of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, who were sent to the Far-East as Apostolic vicariate.[17][18][19]

Due to the strong opposition of Portugal and the death of Pope Innocent X the project was stalled for several years however, until the candidates to the missions decided to go by themselves to Rome in June 1657.[9]

Appointment of missionary bishops

On 29 July 1658, the two chief founders of the Paris Foreign Missions Society were appointed as bishops in the Vatican, becoming Pallu, Bishop of Heliopolis in Augustamnica, Vicar Apostolic of Tonkin, and Lambert de la Motte, Bishop of Berytus, Vicar Apostolic of Cochinchina.[20] On 9 September 1659, the papal bull Super cathedram principis apostolorum by Pope Alexander VII defined the territories they would have to administer: for Pallu, Tonkin, Laos, and five adjacent provinces of southern China (Yunnan, Guizhou, Huguang, Sichuan, Guangxi), for Lambert de la Motte, Cochinchina and five provinces of southeastern China (Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, Jiangxi, Hainan).[20] In 1660 the third founder was appointed as Cotolendi, Bishop of Metellopolis, Vicar Apostolic of Nanjing, with also five provinces of China,[20] namely Beijing, Shanxi, Shandong, Korea and Tartary.

All of them were nominated bishops in partibus infidelium ("In areas of the Infidels", i.e., Heliopolis, Beirut, Metellopolis etc...), receiving long-disappeared bishopric titles from areas that had been lost, in order not to compromise contemporary bishopric titles and avoid conflicts with the bishoprics established through the padroado system.[13] In 1658 also, François de Laval was nominated Vicar Apostolic of Canada,[21] and Bishop of Petra in partibus infidelium, becoming the first Bishop of New France, and in 1663 he would found the Séminaire de Québec with the support of the Paris Foreign Missions Society.[22]

The society itself ("Assemblée des Missions") was formally established by the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement in 1658.[23] The object of the new society was and is still the evangelization of non-Christian countries, by founding churches and raising up a native clergy under the jurisdiction of the bishops. The Society was officially recognized in 1664.[24] The creation of the Paris Foreign Missions Society coincided with the establishment of the French East India Company.

In order to dispatch the three missionaries to Asia, the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement established a trading company (the "Compagnie de Chine", founded 1660). A ship, the Saint-Louis, was built in the Netherlands by the shipowner Fermanel, but the ship foundered soon after being launched.[25] At the same time, the establishment of a trading company and the perceived threat of French missionary efforts to Asia was met with huge opposition by the Jesuits, the Portuguese, the Dutch and even the Propaganda, leading to the issuing of an interdiction of the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement by Cardinal Mazarin in 1660.[26] In spite of these events, the King, the Assembly of the French Clergy, the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement and private donors accepted to finance the effort, and the three bishop managed to depart, although they now had to travel on land.[26]

The three bishops chosen for Asia left France (1660–62) to go to their respective missions, and crossed Persia and India on foot, since Portugal would have refused to take non-Padroado missionaries by ship, and the Dutch and the English refused to take Catholic missionaries.[6] Lambert left Marseilles on 26 November 1660, and reached Mergui in Siam 18 months later, Pallu joined Lambert in the capital of Siam Ayutthaya after 24 months overland, and Cotolendi died upon arrival in India on 6 August 1662.[6] Siam thus became the first country to receive the evangelization efforts of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, to be followed by new missions years later in Cochinchina, Tonkin and parts of China.[6]

Founding principles

The mission had the objective of adapting to local customs, establishing a native clergy, and keeping close contacts with Rome.[6] In 1659, instructions were given by the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (known as the "Propaganda"):

"Here is the principal reason which determined the Sacred Congregation to send you as Bishops in these regions. It is that you endeavour, by all possible means and methods, to educate young people so as to make them capable of receiving priesthood."

— Extract from the 1659 Instructions, given to Pallu and Lambert de la Motte by the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith.[27]

Instructions were also given to the effect that respecting the habits of the countries to be evangelized was paramount, a guiding principle of the missions ever since:

"Do not act with zeal, do not put forward any arguments to convince these peoples to change their rites, their customs or their usages, except if they are evidently contrary to the religion and morality. What would be more absurd than to bring France, Spain, Italy or any other European country to the Chinese? Do not bring to them our countries, but instead bring to them the faith, a faith that does not reject or hurt the rites, nor the usages of any people, provided that these are not distasteful, but that instead keeps and protects them."

— Extract from the 1659 Instructions, given to Pallu and Lambert de la Motte by the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith.[28]

Establishment on Rue du Bac, Paris

The seminary (Séminaire des Missions Étrangères) was created in March 1663. Jean Duval, ordained under the name Bernard de Sainte Thérèse and nominated Bishop of Babylon (modern Iraq) in 1638, offered the deserted buildings of his own Seminary for Missions to Persia, which he had created in 1644 at 128 Rue du Bac.[23] On 10 March 1664, Vincent de Meur was nominated as the first director of the seminary, and officially became superior of the seminary on 11 June 1664.

The seminary was established so that the society might recruit members and administer its property, through the actions of the Compagnie du Saint-Sacrement and by the priests whom the vicars Apostolic had appointed their agents. This house, whose directors were to form young priests to the apostolic life and transmit to the bishops the offerings made by charity, was, and still is situated in Paris in the Rue du Bac.

Known from the beginning as the Seminary of Foreign Missions, it secured the approval of Pope Alexander VII, and the legal recognition of the French government and Louis XIV in 1663. In 1691 the chapel was established, and in 1732 the new, larger, building was completed.[23]

Another wing, perpendicular to the 1732 one, was added in the 19th century to accommodate the great increase in members of the seminary.

1658–1800

The chief events of this period were: the publication of the book Institutions apostoliques, which contains the germ of the principles of the rule, the foundation of the general seminary in Ayutthaya, Siam[29] (the Seminary of Saint Joseph,[30] at the origin of the College General now in Penang, Malaysia), the evangelization of Tonkin, Cochinchina, Cambodia, and Siam, where more than 40,000 Christians were baptized, the creation of an institute of Vietnamese nuns known as "Lovers of the Cross", the establishment of rules among catechists, and the ordination of thirty native priests. Between 1660 and 1700 about 100 missionaries were sent to Asia.[4]

Siam

The Paris Foreign Missions Society started its work in Siam, with the establishment of a base in its capital Ayutthaya. Siam was known to be highly tolerant of other religions and was the only country in Southeast Asia where the Catholic fathers could establish a base safely.[32] With the agreement of the Siamese king Narai, the Seminary of Saint Joseph was established, which could educate Asian candidate priests from all the countries of the Southeast Asian peninsula. A cathedral was also constructed. The college remained in Siam for a century, until the conquest of Siam by Burma in 1766.[31]

The missionary work also had political effects: through their initiative a more active trade was established among Indo-China, the Indies, and France; embassies were sent from place to place; and treaties were signed. In 1681, Jacques-Charles de Brisacier was elected superior of the organization. In 1681 or 1682, the Siamese king Narai, who was seeking to reduce Dutch and English influence, named the French medical missionary Brother René Charbonneau, a member of the Siam mission, as Governor of Phuket . Charbonneau held the position of Governor until 1685.[33] In 1687 a French expedition to Siam took possession of Bangkok, Mergui, and Jonselang. France came close to ruling an Indo-Chinese empire, though it failed following the 1688 Siamese revolution, which adversely affected the missions. Louis Laneau of the society was involved in these events.[6] He was imprisoned by the government for two years, with half of the members of the Seminar, until he was allowed to resume his activities.

In 1702, Artus de Lionne, Bishop of Rosalie, and missionary of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, brought Arcadio Huang to France as one of the first Chinese men there. He established the basis for the study of the Chinese language in France.

In the second half of the 18th century, the society was charged with the missions which the Jesuits had possessed in India prior to suppression of the order in Portugal. Many of the Jesuits remained in Asia. The missions took on a new life, especially in Sichuan (see Catholic Church in Sichuan), under bishops Pottier and Dufresse, and in Cochinchina.

Cochinchina

In Cochinchina, Pigneau de Behaine acted as an agent for Nguyễn Phúc Ánh, a pretender to the throne, in making a treaty with France (the 1787 Treaty of Versailles). Pigneau de Behaine assisted Nguyễn Phúc Ánh in obtaining the support of several French soldiers and officers, modernizing his army, and ultimately gaining victory over the Tây Sơn.

French revolution

At the end of the 18th century, the French Revolution halted the growth of the society, which had previously been very rapid. At that time it had six bishops, a score of missionaries, assisted by 135 native priests; in the various missions there were nine seminaries with 250 students, and 300,000 Christians.[7] Each year the number of baptisms rose on an average of 3000 to 3500; that of infant baptisms in articulo mortis was more than 100,000.

Nineteenth century

On 23 March 1805, Napoleon signed a decree reinstating the Paris Foreign Missions Society.[34] In 1809 however, following a conflict with the Pope, Napoleon cancelled his decision. The Missions would be firmly re-established through a decree by Louis XVIII in March 1815.[35]

Several causes contributed to the rapid growth of the society in the 19th century; chiefly the charity of the Propagation of the Faith and the Society of the Holy Childhood. Each bishop received annually 1200 francs, each mission had its general needs and works allowance, which varied according to its importance, and could amount to from 10,000 to 30,000 francs.

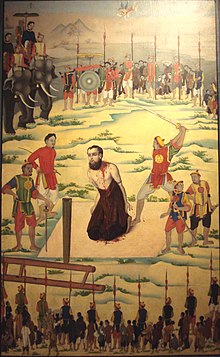

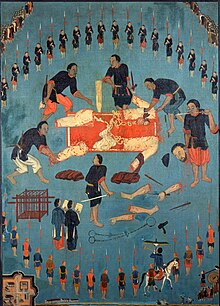

The second cause was persecution. Fifteen missionaries died in prison or were beheaded during the 17th and 18th centuries and the beginning of the 19th century; but after that those killed among the missionaries were very numerous. (See Martyr Saints of China). Altogether, about 200 MEP missionaries died of violent death. Among them 23 were beatified, of whom 20 were canonized,[36] with an additional 3 in 2000.

Authors such as Chateaubriand, with his Génie du christianisme, also contributed to the recovery of the militant spirit of Catholicism, after the troubles of the French Revolution.[37]

By 1820, the territory of the Missions, which included India since the prohition of the Company of Jesus (the Jesuits) in 1776, extended to Korea, Japan, Manchuria, Tibet, Burma, Malaysia etc...[7]

In the 19th century, the local persecutions of missionary priests of the Paris Foreign Missions Society was often a pretext for French military intervention in Asia,[7] based on the doctrine of the Protectorate of missions. These persecutions were described in Europe by books, pamphlets, annals, and journals, inspiring numerous young men either with the desire for martyrdom or that of evangelization. They played a part in inspiring European nations, especially France and England, to intervene in Indochina and China.[7]

Another cause of the progress of the missionaries was the ease and frequency of communication in consequence of the invention of steam and the opening of the Suez Canal. A voyage could be made safely in one month which formerly required eight to ten months amid many dangers. In Vietnam, the persecutions of numerous priests such as Pierre Borie or Augustin Schoeffer was used as a justification for the armed interventions of Jean-Baptiste Cécille and Charles Rigault de Genouilly, ultimately leading to the occupation of Vietnam and the creation of French Indochina. In Korea, the beheading of Siméon-François Berneux and other priests justified the 1866 French Campaign against Korea.

Vietnam

In 1825, emperor Minh Mạng, the son and successor of Gia Long, prohibited foreign missionaries in Vietnam, on the grounds that they perverted the people. The prohibition proved largely ineffective, as missionaries continued their activities in Vietnam, and participated in armed rebellions against Minh Mạng, as in the Lê Văn Khôi revolt (1833–1835). He banned Catholicism completely, as well as French and Vietnamese priests (1833–1836), leading to persecutions of French missionaries.[38] These included the martyrdom of Joseph Marchand in 1835 or Pierre Borie in 1838. These events served in France to stoke a desire among young men to intervene and protect the Catholic faith.

Ming Man's successor, Thiệu Trị, upheld the anti-Catholic policy of his predecessor. In 1843, the French Foreign Minister François Guizot sent a fleet to Vietnam under Admiral Jean-Baptiste Cécille and Captain Charner,.[39] The action also was related to the British successes in China in 1842, and France hoped to be able to establish trade with China from the south. The pretext was to support British efforts in China, and to fight the persecution of French missionaries in Vietnam.[40]

In 1847, Cécille sent two warships (Gloire and Victorieuse) under Captain Lapierre to Da Nang (Tourane) in Vietnam to obtain the release of two imprisoned French missionaries, Bishop Dominique Lefèbvre (imprisoned for a second time as he had re-entered Vietnam illegally) and Duclos, and freedom of worship for Catholics in Vietnam.[39][41] As negotiations drew on without results, on 15 April 1847, a fight named the Bombardment of Đà Nẵng erupted between the French fleet and Vietnamese ships, three of which were sunk as a result. The French fleet sailed away.[41]

Other missionaries were martyred during the reign of Emperor Tự Đức, such as Augustin Schoeffer in 1851 and Jean Louis Bonnard in 1852, prompting the Paris Foreign Missions Society to ask the French government for a diplomatic intervention.[42] In 1858, Charles Rigault de Genouilly attacked Vietnam under the orders of Napoleon III following the failed mission of diplomat Charles de Montigny. His stated mission was to stop the persecution of Catholic missionaries in the country and assure the unimpeded propagation of the faith.[43] Rigault de Genouilly, with 14 French gunships, 3,000 men and 300 Filipino troops provided by the Spanish,[44] attacked the port of Da Nang in 1858, causing significant damage, and occupying the city. After a few months, Rigault had to leave due to problems with supplies and illnesses among many of his troops.[45] Sailing south, De Genouilly captured Saigon, a poorly defended city, on 18 February 1859. This was the beginning of the French conquest of Cochinchina.

Ten martyrs of the M.E.P. were canonized by John-Paul II, 19 June 1988, as part of 117 martyrs of Vietnam, including 11 Dominican priests, 37 Vietnamese priests, and 59 Vietnamese laics:

- François-Isidore Gagelin (1833)

- Joseph Marchand (1835)

- Jean-Charles Cornay (1837)

- François Jaccard (1838)

- Bishop Pierre Borie, vicar apostolic of Western Tonking (1838)

- Augustin Schoeffler (1851)

- Jean-Louis Bonnard (1852)

- Pierre-François Néron (1860)

- Théophane Vénard (1861)

- Bishop Étienne-Théodore Cuenot, vicar apostolic of Eastern Cochinchina (1861)

-

Native priests of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, in western Tonkin.

-

Jules Paspin, of the MEP. Died of malnutrition in Vietnam in 1856.

Korea

In the mid-19th century that the first western Catholic missionaries began to enter Korea. This was done by stealth, either via the Korean border with Manchuria or the Yellow Sea. These French missionaries of the Paris Foreign Missions Society arrived in Korea in the 1840s to proselytize to a growing Korean flock that had in fact independently introduced Catholicism into Korea but needed ordained ministers.

1839 persecutions

On 26 April 1836, Laurent-Joseph-Marius Imbert of the Paris Foreign Missions Society was appointed Vicar Apostolic of Korea and Titular Bishop of Capsa. On 14 May 1837, he was ordained Titular Bishop of Capsa and crossed secretly from Manchuria to Korea the same year. On 10 August 1839, Bishop Imbert, who was secretly going about his missionary work, was betrayed. He was taken to Seoul where he was tortured to reveal the whereabouts of foreign missionaries. He wrote a note to his fellow missionaries, Pierre-Philibert Maubant and Jacques-Honoré Chastan, asking them to surrender to the Korean authorities as well. They were taken before an interrogator and questioned for three days to reveal the names and whereabouts of their converts. As torture failed to break them down, they were sent to another prison and beheaded on 21 September 1839 at Saenamteo. Their bodies remained exposed for several days but were finally buried on Noku Mountain.

1866 persecutions

Bishop Siméon-François Berneux, appointed in 1856 as head of the infant Korean Catholic church, estimated in 1859 that the number of Korean faithful had reached nearly 17,000. At first the Korean court turned a blind eye to such incursions. This attitude changed abruptly, however, with the enthronement of King Gojong in 1864. By the time the Heungseon Daewongun assumed de facto control of the government in 1864 there were twelve French Paris Foreign Missions Society priests living and preaching in Korea and an estimated 23,000 native Korean converts.

In January 1866 Russian ships appeared on the east coast of Korea demanding trading and residency rights in what seemed an echo of the demands made on China by other western powers. Native Korean Christians, with connections at court, saw in this an opportunity to advance their cause and suggested an alliance between France and Korea to repel the Russian advances, suggesting further that this alliance could be negotiated through Bishop Berneux. The Heungseon Daewongun seemed open to this idea, though it is uncertain whether this was ruse to bring the head of the Korean Catholic Church out into the open. Berneux was summoned to the capital, but upon his arrival in February 1866, he was seized and executed. A roundup then began of the other French Catholic priests and native converts.

As a result of the Korean dragnet all but three of the French missionaries were captured and executed: among them were Siméon Berneux, Antoine Daveluy, Just de Bretenières, Louis Beaulieu, Pierre Henri Dorié, Pierre Aumaître, Luc Martin Huin, all of them members of the Paris Foreign Missions Society and canonized by Pope John Paul II on 6 May 1984. An untold number of Korean Catholics also met their end (estimations run around 10,000),[47] many being executed a place called Jeoldu-san in Seoul on the banks of the Han River. In late June 1866 one of the three surviving French missionaries, Felix-Claire Ridel, managed to escape via a fishing vessel and make his way to Tianjin, China in early July 1866. Fortuitously in Tianjin at the time of Ridel's arrival was the commander of the French Far Eastern Squadron, Rear Admiral Pierre-Gustave Roze. Hearing of the massacre and the affront to French national honor, Roze determined to launch a punitive expedition, the French Campaign against Korea, 1866.

Ten martyrs of the M.E.P. were canonized by John-Paul II, 6 May 1984, as part of 103 canonized martyrs of Korea, including André Kim Tegong, the first Korean priest, and 92 Korean laics:

- Bishop Laurent Imbert (21 September 1839)

- Pierre Maubant (21 September 1839)

- Jacques Chastan (21 September 1839)

- Bishop Siméon Berneux (8 March 1866)

- Just de Bretenières (8 March 1866)

- Louis Beaulieu (8 March 1866)

- Pierre-Henri Dorie (8 March 1866)

- Bishop Antoine Daveluy (30 March 1866)

- Pierre Aumaître (30 March 1866)

- Martin-Luc Huin (30 March 1866)

China

Auguste Chapdelaine, who was preaching illegally in China, was imprisoned, tortured and killed by Chinese authorities in 1856. This event, named the "Father Chapdelaine Incident" became the pretext for the French military intervention in the Second Opium War.[48][49][50]

Three missionaries of the M.E.P. were canonized by Pope John-Paul II on 1 October 2000, as part of 120 Martyrs of China, including 9 Franciscans, 6 Dominicans, 7 Franciscan missionary sisters of Mary, 1 Lazarist, 1 Italian priest of the Foreign Missions of Milan, 4 Chinese priests and 83 Chinese laics:

- Bishop Gabriel-Taurin Dufresse, Vicar Apostolic of Szechwan, martyred in Chengdu (1815)

- Auguste Chapdelaine, martyred in Guangxi (29 February 1856)

- Jean-Pierre Néel, martyred in Guizhou (1862)

-

Gabriel-Taurin Dufresse, martyred in Chengdu in 1815.

-

Pierre Dumont, died fleeing a Muslim revolt in Yunnan in 1856.

-

Auguste Chapdelaine, martyred in Guangxi in 1856.

-

Jean-Pierre Néel, martyred in Guizhou in 1862.

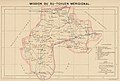

Mission areas

-

Tibetan Mission (part 1)

-

Tibetan Mission (part 2)

Japan

After the suppression of Christianity in Japan from around 1620 and nearly two century of strictly enforced seclusion thereafter, various contacts occurred from the middle of the 19th century as France was trying to expand its influence in Asia. After the signature of the Treaty of Nanking by Great Britain in 1842, both France and the United States tried to increase their efforts in the Orient.

The first attempts at resuming contacts occurred with the Ryūkyū Kingdom (modern Okinawa), a vassal of the Japanese fief of Satsuma since 1609. In 1844, a French naval expedition under Captain Fornier-Duplan onboard Alcmène visited Okinawa on 28 April 1844. Trade was denied, but Father Forcade of the Paris Foreign Missions Society was left behind with a Chinese translator, named Auguste Ko. Forcade and Ko remained in the Temple of Amiku, city of Tomari, under strict surveillance, only able to learn the Japanese language from monks. After a period of one year, on 1 May 1846, the French ship Sabine, commanded by Guérin, arrived, soon followed by La Victorieuse, commanded by Charles Rigault de Genouilly, and Cléopâtre, under Admiral Cécille. They came with the news that Pope Gregory XVI had nominated Forcade Bishop of Samos and Vicar Apostolic of Japan.[51] Cécille offered the kingdom French protection against British expansionism, but in vain, and only obtained that two missionaries could stay.

Forcade and Ko were picked up to be used as translators in Japan, and Leturdu was left in Tomari, soon joined by Mathieu Adnet. On 24 July 1846, Admiral Cécille arrived in Nagasaki, but failed in his negotiations and was denied landing, and Bishop Forcade never set foot in mainland Japan.[52] The Ryu-Kyu court in Naha complained in early 1847 about the presence of the French missionaries, who had to be removed in 1848.

France would have no further contacts with Okinawa for the next 7 years, until news came that Commodore Perry had obtained an agreement with the islands on 11 July 1854, following his treaty with Japan. France sent an embassy under Rear-Admiral Cécille onboard La Virginie in order to obtain similar advantages. A convention was signed on 24 November 1855.

As contacts between France and Japan developed during the Bakumatsu period (on the military side this is the period of the first French military mission to Japan), Japan was formed into a unique Vicariate Apostolic from 1866 until 1876. The Vicariate was administered by Bernard Petitjean, of the Paris Foreign Missions Society (1866–1884).[2]

20th century

The following table shows the state of the missions at the turn of the 20th century:[2]

Missions of Japan and KoreaTotal numbers

|

Missions of China and Tibet

Total numbers

|

Missions of Eastern Indo-China

Total numbers

|

Missions of Western Indo-ChinaTotal numbers

|

Missions of IndiaTotal numbers

|

A sanatorium for sick missionaries was established in Hong Kong (Béthanie);[53][2] another in India among the Nilgiri mountains, and a third in France. In Hong Kong there were also a house of spiritual retreat and a printing establishment (Nazareth) which published works of art of the Far East – dictionaries, grammars, books of theology, piety, Christian doctrine, and pedagogy.[54][55][2] Houses of correspondence, or agencies, were established in the Far East, in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Saigon, Singapore, and one in Marseilles, France.[2]

Exhibits

The crypt at the Paris Foreign Missions Society headquarters located Rue du Bac houses a permanent display called "Salle des Martyrs" ("Room of the Martyrs"). Numerous artifacts are on display, mainly remains and relics of martyred members of the missions, depictions of various martyrdoms endured during the history of the missions, and objects related to the Catholic Faith in the various countries of Asia. Also, historical archives and graphic material are available, regarding the details of the missions. The Salle des Martyrs can be visited for free from Tuesday to Saturday, from 11:00 to 18:30, and on Sundays from 13:00 to 18:00.

Another, much larger, exhibition is located on the ground floor of the main building of the Paris Foreign Missions Society. Established as a temporary exhibition in 2007–2008, it remains in place but is now closed to the general public. It is only opened for visits once a year during the free-access "Journée des Musées Nationaux", although there seem to be plans to make it a permanent exhibition in the near future.

-

Portrait of Vietnamese crown prince Nguyễn Phúc Cảnh.

-

Ashes of Pigneau de Behaine.

-

Pigneau's 1772 Dictionarium Anamitico-Latinum.

-

The Society in 1925.

Park

The park of the Paris Foreign Missions Society is the largest private garden in Paris. It houses various significant artifacts, such as a Chinese bell from Canton brought to France by the French Admiral Charles Rigault de Genouilly, a stela to Korean Martyrs and the list of canonized members of the Paris Foreign Missions Society. The park can be visited every Saturday at 15:30.

The French writer Chateaubriand lived in an apartment 120 Rue du Bac, with a view on the park, a fact he mentions in the last paragraph of his Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe:

"As I write these last words, my window, which looks west over the gardens of the Foreign Mission, is open: it is six in the morning; I can see the pale and swollen moon; it is sinking over the spire of the Invalides, scarcely touched by the first golden glow from the East; one might say that the old world was ending, and the new beginning. I behold the light of a dawn whose sunrise I shall never see. It only remains for me to sit down at the edge of my grave; then I shall descend boldly, crucifix in hand, into eternity."

— Chateaubriand Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe Book XLII: Chapter 18[56]

See also

- Timeline of Christian missions

- Catholic religious order

- Society of Saint-Sulpice

- Catholic Church in Asia

- Christianity in Asia

- Chinese Rites controversy

- Category:Paris Foreign Missions Society

- Former French Mission Building in Hong Kong

- Augustine Périé

- Augustin Bourry

Notes

- ^ a b c "Paris Foreign Missions Society (M.E.P.)". GCatholic.org.

- ^ a b c d e f

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Society of Foreign Missions of Paris". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Society of Foreign Missions of Paris". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b "Paris Foreign Missions Society (M.E.P.)".

- ^ a b Asia in the Making of Europe, p.231

- ^ Missions, p.3

- ^ a b c d e f Missions, p.4

- ^ a b c d e Missions, p.5

- ^ a b c Mantienne, p.22

- ^ a b Les Missions étrangères, p.30

- ^ a b c Les Missions Etrangères, p.25

- ^ Mantienne, p.23

- ^ Asia in the Making of Europe, p.232

- ^ a b Mantienne, p.26

- ^ Missions, p.3-4

- ^ Mantienne, p.26-28

- ^ Asia in the Making of Europe, p.232

- ^ Viet Nam By Nhung Tuyet Tran, Anthony Reid p.222

- ^ An Empire Divided by James Patrick Daughton, p.31

- ^ Asia in the Making of Europe, p.229-230

- ^ a b c Les Missions Etrangeres, p.35

- ^ Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society By Anne Goldgar, Robert I. p.25 Note 77 [1]

- ^ A Bibliography of Canadian Imprints, 1751–1800 by Marie Tremaine p.70 [2]

- ^ a b c Mantienne, p.29

- ^ Tran, Anh Q. (2017). Gods, Heroes, and Ancestors: An Interreligious Encounter in Eighteenth-Century Vietnam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190677602. Page 27.

- ^ Mantienne, p.28

- ^ a b Asia in the Making of Europe, p.232

- ^ Les Missions Etrangères, p.37. Original French "Voici la principale raison qui a déterminé la Sacrée Congrégation à vous envoyer revêtus de l'épiscopat dans ces régions. C'est que vous preniez en main, par tous les moyens et méthodes possibles, l'éducation de jeunes gens, de façon à les rendre capable de recevoir le sacerdoce."

- ^ Missions, p.5. Original French: "Ne mettez aucun zèle, n'avancez aucun argument pour convaincre ces peuples de changer leurs rites, leurs coutumes et leur moeurs, à moins qu'ils ne soient évidemment contraires à la religion et à la morale. Quoi de plus absurde que de transporter chez les Chinois la france, l'Espagne, l'Italie, ou quelque autre pays d'Europe? N'introduisez pas chez eux nos pays, mais la foi, cette foi qui ne repousse ni ne blesse les rites, ni les usages d'aucun peuple, pourvu qu'ils ne soient pas détestables, mais bien au contraire veut qu'on les garde et les protège."

- ^ The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia By Nicholas Tarling, p.191

- ^ Asia in the Making of Europe, p.249

- ^ a b Les Missions Etrangeres, p.54

- ^ Les Missions Etrangeres, p.45

- ^ New Terrains in Southeast Asian History, p.294, Abu Talib

- ^ Les Missions Etrangeres, p.135. Article No1 of the decree: "Les établissements des Missions, connus sous la dénomination des Missions étrangères, et le séminaire du Saint-Esprit sont rétablis".

- ^ Les Missions Etrangeres, p.135

- ^ Website of the College General: [3] Archived 22 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Les Missions Etrangeres, p.137

- ^ Dragon Ascending By Henry Kamm p.86

- ^ a b Chapuis, p.5 Google Books Quote: "Two years later, in 1847, Lefebvre was again captured when he returned to Vietnam. This time Cecille sent captain Lapierre to Da Nang. Whether Lapierre was aware or not that Lefebvre had already been freed and on his way back to Singapore, the French first dismantled masts of some Vietnamese ships. Later on 14 April 1847, in only one hour, the French sank the last five bronze-plated vessels in the bay of Da Nang.

- ^ Tucker, p.27

- ^ a b Tucker, p.28

- ^ Les Missions Etrangeres, p.12

- ^ Tucker, p.29

- ^ A History of Vietnam, Oscar Chapuis p.195

- ^ Tucker, p.29

- ^ Source

- ^ "It is estimated than 10,000 were killed within a few months" Source Archived 10 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Religion Under Socialism in China by Zhufeng Luo, Chu-feng Lo, Luo Zhufeng p.42: "France started the second Opium War under the pretext of the "Father Chapdelaine Incident." [4]

- ^ Taiwan in Modern Times by Paul Kwang Tsien Sih p.105: "The two incidents that eventually caused a war were the Arrow incident and the murder of the French Catholic priest, Abbe Auguste Chapdelaine"

- ^ A History of Christian Missions in China p.273 by Kenneth Scott Latourette: "A casus belli was found in an unfortunate incident which had occurred before the Arrow affair, the judicial murder of a French priest, Auguste Chapdelaine" [5]

- ^ The Dublin Review, Nicholas Patrick Wiseman [6]

- ^ Religion in Japan: Arrows to Heaven and Earth By Peter Francis Kornicki, James McMullen (1996) Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55028-9, p.162

- ^ Restoration of Béthanie: now the home of Emmanuel Church - Pokfulam, Hong Kong

- ^ Béthanie and Nazareth: French Secrets from a British Colony. Alain Le Pichon. Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts. 15 December 2006. ISBN 988-99438-0-8. ISBN 978-988-99438-0-6

- ^ "The history of Nazareth which was previously known as Douglas Castle and is now University Hall". Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Chateaubriand Mémoires d'Outre-Tombe Book XLII: Chapter 18

References

- Mantienne, Frédéric (1999) Monseigneur Pigneau de Béhaine (Eglises d'Asie, Série Histoire, ISSN 1275-6865) ISBN 2-914402-20-1

- Missions étrangères de Paris. 350 ans au service du Christ 2008 Editeurs Malesherbes Publications, Paris ISBN 978-2-916828-10-7

- Les Missions Etrangères. Trois siècles et demi d'histoire et d'aventure en Asie Editions Perrin, 2008, ISBN 978-2-262-02571-7

Further reading

- Adrien Launay (1898), Histoire des missions de l'Inde, 5 vols.