Olympian Games

| Olympic Games |

|---|

|

| Main topics |

| Games |

| Regional games |

| Defunct games |

The ancient Olympic Games (Ancient Greek: τὰ Ὀλύμπια, ta Olympia[1]), or the ancient Olympics, were a series of athletic competitions among representatives of city-states and one of the Panhellenic Games of ancient Greece. They were held at the Panhellenic religious sanctuary of Olympia, in honor of Zeus, and the Greeks gave them a mythological origin. The originating Olympic Games are traditionally dated to 776 BC.[2] The games were held every four years, or Olympiad, which became a unit of time in historical chronologies. These Olympiads were referred to based on the winner of their stadion sprint, e.g., "the third year of the eighteenth Olympiad when Ladas of Argos won the stadion".[3] They continued to be celebrated when Greece came under Roman rule in the 2nd century BC. Their last recorded celebration was in AD 393, under the emperor Theodosius I, but archaeological evidence indicates that some games were still held after this date.[4][5] The games likely came to an end under Theodosius II, possibly in connection with a fire that burned down the temple of the Olympian Zeus during his reign.[6]

During the celebration of the games, the Olympic truce (ekecheiría) was announced so that athletes and religious pilgrims could travel from their cities to the games in safety. The prizes for the victors were olive leaf wreaths or crowns. The games became a political tool used by city-states to assert dominance over their rival city states. Politicians would announce political alliances at the games, and in times of war, priests would offer sacrifices to the gods for victory. The games were also used to help spread Hellenistic culture throughout the Mediterranean. The Olympics also featured religious celebrations. The statue of Zeus at Olympia was counted as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Sculptors and poets would congregate each Olympiad to display their works of art to would-be patrons.

The ancient Olympics had fewer events than the modern games, and for many years only freeborn Greek men were allowed to participate,[7] although there were victorious women chariot owners. Moreover, throughout their history, the Olympics, both ancient and modern, have occasionally become arenas where political expressions, such as demonstrations, boycotts, and embargoes, have been employed by nations and individuals to exert influence over these sporting events.[8] As long as they met the entrance criteria, athletes from any Greek city-state and kingdom were allowed to participate. The games were always held at Olympia rather than moving between different locations like the modern Olympic Games.[9] Victors at the Olympics were honored, and their feats chronicled for future generations.

Origin myths

To the ancient Greeks, it was important to root the Olympic Games in mythology.[10] During the time of the ancient games their origins were attributed to the gods, and competing legends persisted as to who actually was responsible for the genesis of the games.[11] The patterns that emerge from these legends are that the Greeks believed the games had their roots in religion, that athletic competition was tied to worship of the gods, and the revival of the ancient games was intended to bring peace, harmony and a return to the origins of Greek life.[12]

These origin traditions have become nearly impossible to untangle, yet a chronology and patterns have arisen that help people understand the story behind the games.[13] Greek historian Pausanias provides a story about the dactyl Heracles (not to be confused with the Hercules who was the son of Zeus and joined the Roman pantheon) and four of his brothers, Paeonaeus, Epimedes, Iasius and Idas, who raced at Olympia to entertain the newborn Zeus. He crowned the victor with an olive wreath (which thus became a peace symbol), which also explains the four-year interval, bringing the games around every fifth year (counting inclusively).[14][15] The other Olympian gods (so named because they lived permanently on Mount Olympus) would also engage in wrestling, jumping and running contests.[16]

Another myth of the origin of the games is the story of Pelops, a local Olympian hero. Oenomaus, the king of Pisa, had a daughter named Hippodamia, and according to an oracle, the king would be killed by her husband. Therefore, he decreed that any young man who wanted to marry his daughter was required to drive away with her in his chariot, and Oenomaus would follow in another chariot, and spear the suitor if he caught up with them. Now, the king's chariot horses were a present from the god Poseidon and therefore supernaturally fast. The king's daughter fell in love with a man called Pelops. Before the race however, Pelops persuaded Oenomaus' charioteer Myrtilus to replace the bronze axle pins of the king's chariot with wax ones. Naturally, during the race, the wax melted and the king fell from his chariot and was killed. After his victory, Pelops organized chariot races as a thanksgiving to the gods and as funeral games in honor of King Oenomaus, in order to be purified of his death. It was from this funeral race held at Olympia that the beginnings of the Olympic Games were inspired. Pelops became a great king, a local hero, and he gave his name to the Peloponnese.

One (later) myth, attributed to Pindar, states that the festival at Olympia involved Heracles, the son of Zeus: According to Pindar, Heracles established an athletic festival to honor his father, Zeus, after he had completed his labors.

History

Prehistory

Areas around the Mediterranean had a long tradition of physical activities, even though they did not seem to hold regular competitions, with the events being probably the preserve of kings and upper classes.[17] The earliest evidence of athletic tradition in Greece come from late Bronze Age artistic representations, such as from the island of Crete and Thera, and Archaic literary texts.[18] The Minoan culture centered on Crete engaged in gymnastics, with bull-leaping, tumbling, running, wrestling and boxing shown on their frescoes. The Mycenaeans adopted Minoan games and also raced chariots in religious or funerary ceremonies.[19][20] The exact relation between the early Minoan and Mycenaean sporting activities and the later Greek practicies remains elusive.[21] The heroes of Homer's epics, composed around 750 BC and held to represent a late Bronze Age society, participate in athletic competitions to honor the dead. In the Iliad there are chariot races, boxing, wrestling, a foot race, as well as fencing, archery, and spear throwing. The Odyssey adds to these a long jump and discus throw.[22][23]

First games

Aristotle reckoned the date of the first Olympics to be 776 BC, a date largely accepted by most, though not all, subsequent ancient historians.[25] To this day, this is the conventional given date for the inception of the ancient Olympics and, while this specific date of origin cannot be verified, it is generally accepted that the games date from some time in the eighth century BC.[26] Archaeological finds confirm, approximately, the Olympics starting at or soon after this time.[27]

Archaeology suggests that major games at Olympia arose probably around 700. Christesen's important work on the Olympic victor lists shows that victors' names and details were unreliable until the sixth century. Elis's independent state administered it, and while the Eleans managed the games well, there sometimes was bias and interference. Also, despite modern illusions, the famous Olympic truce only mandated safe passage for visitors; it did not stop all wars in Greece or even at Olympia.[28]

Olympiad calendar

The historian Ephorus, who lived in the fourth century BC, is one potential candidate for establishing the use of Olympiads to count years, although credit for codifying this particular epoch usually falls to Hippias of Elis, to Eratosthenes, or even to Timaeus, whom Eratosthenes may have imitated.[29][30][31] The Olympic Games were held at four-year intervals, and later, the ancient historians' method of counting the years even referred to these games, using Olympiad for the period between two games. Previously, the local dating systems of the Greek states were used (they continued to be used by everyone except historians), which led to confusion when trying to determine dates. For example, Diodorus states that there was a solar eclipse in the third year of the 113th Olympiad, which must be the eclipse of 316 BC. This gives a date of (mid-summer) 765 BC for the first year of the first Olympiad.[32] Nevertheless, there is disagreement among scholars as to when the games began.[33]

According to the later Greek traveler Pausanias, who wrote in 175 AD, the only competition held at first was the stadion, a race over about 190 metres (620 feet).[34] The word stadium is derived from this event.

Early history

Several groups fought over control of the sanctuary at Olympia, and hence the games, for prestige and political advantage. Pausanias later writes that in 668 BC, Pheidon of Argos was commissioned by the town of Pisa to capture the sanctuary from the town of Elis, which he did and then personally controlled the games for that year. The next year, Elis regained control.

Greek sports also derived its origins from the concept that physical energy was being expended in a ritualistic manner, in which Paleolithic age hunting practices were turned into a more socially and glamorized function, thus becoming sport. The Greeks in particular were unique in the regard that their competitions were often held in grand facilities, with prizes and nudity that stressed the Greek idealisms of training one's body to be as fit as their mind. It is this ideology and athletic exceptionalism that resulted in theories claiming the Greeks were the inventors of sport.[35]

In the first 200 years of the games' existence, they only had regional religious importance. Only Greeks in proximity to Olympia competed in these early games. This is evidenced by the dominance of Peloponnesian athletes in the victors' roles.[36] Over time, the Olympic Games gained increasing recognition and became part of the Panhellenic Games, four separate games held at two- or four-year intervals, but arranged so that there was at least one set of games every year. The other Panhellenic Games were the Pythian, Nemean, and Isthmian Games, though the Olympic Games, being the oldest among the rest, were considered the most prestigious.[37] The Olympic games were held to be one of the two central rituals in ancient Greece, the other being the much older religious festival, the Eleusinian Mysteries.[38]

Participation in the Olympic Games was reserved for freeborn Greek men, although there were also Greek women who were victorious as chariot owners. Authorities differ as to whether females were allowed to attend the competitions. Some say all females were excluded from the sacred precinct where the games took place,[39] while others cite Pausanias who indicated that parthenoi (maidens) could view the competitions, but not gynaikes (married women), who had to remain on the south side of the river Alpheios.[40] The evidence regarding the attendance of women in the Olympics is inconclusive. Nevertheless, there is no specific evidence suggesting that women were excluded from attending the other Panhellenic or Panathenaic contests.[41]

Imperial period

Roman conquest of Greece

After the Roman conquest of Greece the Olympics continued but the event declined in popularity throughout the pre-Augustan era. During this period, Romans largely concentrated on domestic problems, and paid less attention to their provinces. The fact that all equestrian victors were from the immediate locality and that there is a "paucity of victor statues in the Altis" from this period suggests the games were somewhat neglected.[42]

In 86 BC the Roman general Sulla robbed Olympia and other Greek treasuries to finance a war. He was the only Roman to commit violence against Olympia.[42] Sulla hosted the games in 80 BC (the 175th Olympiad) as a celebration of his victories over Mithridates. Supposedly the only contest held was the stadion race because all the athletes had been called to Rome.[43]

Augustus

Under the rule of emperor Augustus the Olympics underwent a revival. Before he came to full power, Augustus' right-hand man Marcus Agrippa restored the damaged temple of Zeus and in 12 BC Augustus asked King Herod of Judea to subsidize the games.

After Augustus was declared a god by the Senate after his death, a statue of his likeness was commissioned at Olympia.[44] Subsequent divine emperors also had statues erected within the sacred Altis. The stadium was renovated at his command and Greek athletics in general were subsidized.[45]

Nero

One of the most infamous events of Olympic history occurred under the rule of Nero. He desired victory in all chariot races of the Panhellenic Games in a single year, so he ordered the four main hosts to hold their games in AD 67, and therefore the scheduled Olympics of 65, in the 211th Olympiad, were postponed. At Olympia he was thrown from his chariot, but still claimed victory. Nero also considered himself a talented musician, so he added contests in music and singing to those festivals that lacked them, including the Olympics. Nero won all of those contests, no doubt because judges were afraid to award victory to anyone else. After his suicide, the Olympic judges had to repay the bribes he had bestowed and declared the "Neronian Olympiad" to be void.[45]

Renaissance

In the first half of the second century, the Philhellenic emperors, Hadrian and Antoninus Pius oversaw a new and successful phase in the history of the games. The Olympics attracted a great number of spectators and competitors and the victors' fame spread across the Roman Empire. The renaissance endured for most of the second century. Once again, "philosophers, orators, artists, religious proselytizers, singers, and all kinds of performers went to the festival of Zeus."[46]

Decline

The 3rd century saw a decline in the popularity of the games. The victory list of Africanus ends at the 249th Olympiad (217), though Moses of Chorene's History of Armenia lists a boxing winner from as late as 369 (the 287th Olympiad).[47] Excavated inscriptions also show the games continued past 217. Until recently the last securely datable winner was Publius Asclepiades of Corinth who won the pentathlon in 241 (the 255th Olympiad). In 1994, a bronze plaque was found inscribed with victors of the combative events hailing from the mainland and Asia Minor; proof that an international Olympic Games continued until at least 385 (the 291st Olympiad).[48]

The games continued past 385, by which time flooding and earthquakes had damaged the buildings and invasions by barbarians had reached Olympia.[49] The last recorded games were held under Theodosius I in 393 (at the start of the 293rd Olympiad), but archeological evidence indicates that some games were still held.[4][5]

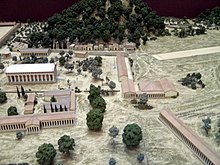

Location

Areas of note: 2: Prytaneion, 4: Temple of Hera, 5: Pelopion, 10: Stadium, 15: Temple of Zeus, 20: Gymnasium, 21: Palaestra, 26: Greek Baths, 29: Leonidaion, 31: Bouleuterion

Olympia lies in the valley of the Alfeiós River (Romanized as Alpheus) in the western part of the Peloponnese, today around 18 km (11 mi) away from the Ionian Sea but perhaps, in antiquity, half that distance.[50] The Altis, as the sanctuary as was originally known, was an irregular quadrangular area more than 180 meters (590.5 feet) on each side and walled except to the North where it was bounded by the Mount Kronos.[51] It consisted of a somewhat disordered arrangement of buildings, the most important of which are the Temple of Hera, the Temple of Zeus, the Pelopion and the area of the great altar of Zeus, where the largest sacrifices were made. The name Altis was derived from a corruption of the Elean word also meaning "the grove" because the area was wooded, olive and plane trees in particular.[52]

Uninhabited throughout the year, when the games were held the site became over congested. There were no permanent living structures for spectators, who, rich or poor, made do with tents. Ancient visitors recall being plagued by summer heat and flies; such a problem that sacrifices were made to Zeus Averter of Flies. The site's water supply and sanitation were finally improved after nearly a thousand years, by the mid-second century AD.[53]

But you may say, there are some things disagreeable and troublesome in life. And are there none at Olympia? Are you not scorched? Are you not pressed by a crowd? Are you not without comfortable means of bathing? Are you not wet when it rains? Have you not abundance of noise, clamour, and other disagreeable things? But I suppose that setting all these things off against the magnificence of the spectacle, you bear and endure.

— Epictetus, 1st century AD

Culture

The ancient Olympics were as much a religious festival as an athletic event. The games were held in honor of the Greek god Zeus, and on the middle day of the games, 100 oxen would be sacrificed to him.[9] Over time, Olympia, the site of the games, became a central spot for the worship of the head of the Greek pantheon and a temple, built by the Greek architect Libon, was erected on the mountaintop. The temple was one of the largest Doric temples in Greece.[9] The sculptor Pheidias created a statue of Zeus made of gold and ivory. It stood 42 feet (13 m) tall. It was placed on a throne in the temple. The statue became one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.[9] As the historian Strabo put it,

... the glory of the temple persisted ... on account both of the festal assembly and of the Olympian Games, in which the prize was a crown and which were regarded as sacred, the greatest games in the world. The temple was adorned by its numerous offerings, which were dedicated there from all parts of Greece.[9]

Artistic expression was a major part of the games. Sculptors, poets, painters and other artisans would come to the games to display their works in what became an artistic competition. Poets would be commissioned to write poems in praise of the Olympic victors. Such victory songs or epinicians, were passed on from generation to generation and many of them have lasted far longer than any other honor made for the same purpose.[54] Pausanias claimed that the destroyed Sicilian polis of Naxos would have been completely forgotten if not for its four-time Olympic champion, Tisandros.[55] Pierre de Coubertin, one of the founders of the modern Olympic Games, wanted to fully imitate the ancient Olympics in every way. Included in his vision was an artistic competition modeled on the ancient Olympics and held every four years, during the celebration of the Olympic Games.[56] His desire came to fruition at the Olympics held in Athens in 1896.[57]

Politics

Establishment

Power in ancient Greece became centered on the city-state (polis) in the 8th century BC.[58] The city-state was a population center organized into a self-contained political entity.[59] Every city-state worshiped the same pantheon of gods, although each one often gave more emphasis on a limited group of deities and celebrated religious festivals based on various calendars.[37] These city-states often lived in close proximity to each other, which created competition for limited resources. Though conflict between the city-states was ubiquitous, it was also in their self-interest to engage in trade, military alliances, and cultural interaction.[60] The city-states had a dichotomous relationship with each other: on one hand, they relied on their neighbors for political and military alliances, while on the other they competed fiercely with those same neighbors for vital resources.[61] In this political context the Olympic Games served as a venue for representatives of the city-states to peacefully compete against each other.[62]

From the 8th century BC onwards, the city-states expanded with the establishment of colonies in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. While their cults and sanctuaries provided a sense of identity, those local identities as well as the increasing contacts with non-Greek populations presented the Greeks with the need to define themselves not only as members of a certain polis but also as Hellenes. That was made possible on the basis of a common language, a body of shared myths and legends, their religious observance and fondness in athletic festivals, which functioned as important factors for the Greek self-definition. As a result, a small number of religious festivals assumed a panhellenic character and were reserved for members of all Greek city-states; the oldest of them being the Olympic Games. A body of officials, known as Hellanodikai, was responsible for determining the city-state of origin and the Greek identity of the competitors.[63]

The spread of Greek colonies in the 6th and 5th centuries BC is repeatedly linked to successful Olympic athletes. For example, Pausanias recounts that Cyrene was founded c. 630 BC by settlers from Thera with Spartan support. The support Sparta gave was primarily the loan of three-time Olympic champion Chionis. The appeal of settling with an Olympic champion helped to populate the colonies and maintain cultural and political ties with the city-states near Olympia. Thus, Hellenic culture and the games spread while the primacy of Olympia persisted.[64]

Olympic truce

During the Olympic Games, a truce, or ekecheiria was observed. Three runners, known as spondophoroi, were sent from Elis to the participant cities at each set of games to announce the beginning of the truce.[65] During this period, armies were forbidden from entering Olympia. Legal disputes and the use of the death penalty were forbidden. The truce — primarily designed to allow athletes and visitors to travel safely to the games — was, for the most part, observed.[65] Thucydides wrote of a situation when the Spartans were forbidden from attending the games, and the violators of the truce were fined 2,000 minae for assaulting the city of Lepreum during the period of the ekecheiria. The Spartans disputed the fine and claimed that the truce had not yet taken hold.[66][67]

The games faced a serious challenge during the Peloponnesian War, which primarily pitted Athens against Sparta, but in reality touched nearly every Hellenic city-state.[68] The Olympics were used during this time to announce alliances and offer sacrifices to the gods for victory.[9][66]

While a martial truce was observed by all participating city-states, no such reprieve from conflict existed in the political arena. The Olympic Games evolved the most influential athletic and cultural stage in ancient Greece, and arguably in the ancient world.[69] As such the games became a vehicle for city-states to promote themselves. The result was political intrigue and controversy. For example, Pausanias, a Greek historian, explains the situation of the athlete Sotades,

Sotades at the ninety-ninth Festival was victorious in the long race and proclaimed a Cretan, as in fact he was. But at the next Festival he made himself an Ephesian, being bribed to do so by the Ephesian people. For this act he was banished by the Cretans.[9]

Events

| Olympiad | Year | Event first introduced |

|---|---|---|

| 1st | 776 BC | Stade |

| 14th | 724 BC | Diaulos |

| 15th | 720 BC | Long-distance race (Dolichos) |

| 18th | 708 BC | Pentathlon, wrestling |

| 23rd | 688 BC | Boxing (pygmachia) |

| 25th | 680 BC | Four horse chariot race (tethrippon) |

| 33rd | 648 BC | Horse race (keles), pankration |

| 37th | 632 BC | Boys' stade and wrestling |

| 38th | 628 BC | Boys' pentathlon (discontinued same year) |

| 41st | 616 BC | Boys' boxing |

| 65th | 520 BC | Hoplite race (hoplitodromos) |

| 70th | 500 BC | Mule-cart race (apene) |

| 71st | 496 BC | Mare horse race (calpe) |

| 84th | 444 BC | Mule-cart race (apene) and mare horse race (calpe), both discontinued |

| 93rd | 408 BC | Two-horse chariot race (synoris) |

| 96th | 396 BC | Competition for heralds and trumpeters |

| 99th | 384 BC | Tethrippon for horse over one year |

| 128th | 268 BC | Chariot for horse over one year |

| 131st | 256 BC | Race for horses older than one year |

| 145th | 200 BC | Pankration for boys |

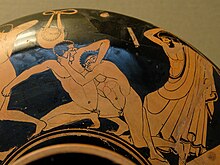

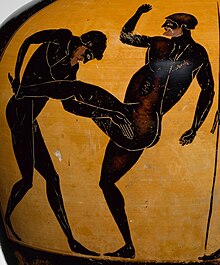

Apparently starting with just a single foot race, the program gradually increased to twenty-three contests, although no more than twenty featured at any one Olympiad.[71] Participation in most events was limited to male athletes, except for women who were allowed to take part by entering horses in the equestrian events. Youth events are recorded as starting in 632 BC. Our knowledge of how the events were performed primarily derives from the paintings of athletes found on many vases, particularly those of the Archaic and Classical periods.[72] Competitors had access to two gymnasiums for training purposes: the Xystos (meaning 'scraped'), an open colonnade or running track,[73] for the runners and pentathletes, and the Tetragono for wrestlers and boxers.[74]

A loincloth known as the perizoma was initially worn by athletes at the ancient Olympic Games.[75] Archaeological evidence from late sixth-century BC reveals athletes sporting this garment during competitions.[75] For most of its history, Olympic events were performed in the nude,[76] a habit which the Greeks felt distinguished them from non-Greeks.[26] Pausanias says that the first naked runner was Orsippus, winner of the stadion race in 720 BC, who simply lost his garment on purpose because running without it was easier.[77] The 5th-century BC historian Thucydides credits the Spartans with introducing the custom of "publicly stripping and anointing themselves with oil in their gymnastic exercises". He continues saying that "formerly, even in the Olympic contests, the athletes who contended wore belts across their middles; and it is but a few years since that the practice ceased."[78]

Running

The only event recorded at the first thirteen games was the stade, a straight-line sprint of just over 192 metres (630 feet).[79] The diaulos (lit. "double pipe"), or two-stade race, is recorded as being introduced at the 14th Olympiad in 724 BC. It is thought that competitors ran in lanes marked out with lime or gypsum for the length of a stade then turned around separate posts (kampteres), before returning to the start line.[80] Xenophanes wrote that "Victory by speed of foot is honored above all."

A third foot race, the dolichos ("long race"), was introduced in the next Olympiad. Accounts of the race's distance differ; it seems to have been from twenty to twenty-four laps of the track, around 7.5 km to 9 km (4.6 to 5.6 mi), although it may have been lengths rather than laps and thus half as far.[81][82]

The last running event added to the Olympic program was the hoplitodromos, or "hoplite race", introduced in 520 BC and traditionally run as the last race of the games. Competitors ran either a single or double diaulos (approximately 400 or 800 metres, 0.25 or 0.5 miles) in full military armour.[83] The hoplitodromos was based on a war tactic of soldiers running in full armor to surprise the enemy.

Combat

Wrestling (pale) is recorded as being introduced at the 18th Olympiad. Three throws were necessary for a win. A throw was counted if the body, hip, back or shoulder (and possibly knee) touched the ground. If both competitors fell nothing was counted. Unlike its modern counterpart Greco-Roman wrestling, it is likely that tripping was allowed.[84]

Boxing (pygmachia) was first listed in 688 BC,[85] the boys' event sixty years later. The laws of boxing were ascribed to the first Olympic champion Onomastus of Smyrna.[84] It appears that body-blows were either not permitted or not practised.[84][86] The Spartans, who claimed to have invented boxing, quickly abandoned it and did not take part in boxing competitions.[84] At first the boxers wore himantes (sing. himas), long leather strips which were wrapped around their hands.[85]

The pankration was one of the most popular sports in the ancient Olympic Games.[87] The pankration was introduced in the 33rd Olympiad (648 BC).[88] Boys' pankration became an Olympic event in 200 BC, in the 145th Olympiad.[89] As well as techniques from boxing and wrestling, athletes also used kicks,[90] locks, and chokes on the ground. Although the only prohibitions were against biting and gouging, the pankration was regarded as less dangerous than boxing.[91]

It was one of the most popular events: Pindar wrote eight odes praising victors of the pankration.[84] A famous event in the sport was the posthumous victory of Arrhichion of Phigalia who "expired at the very moment when his opponent acknowledged himself beaten".[84]

Discus

The discus (diskos) event was similar to the modern competition. Stone and iron diskoi have been found, although the most commonly used material appears to be bronze. To what extent the diskos was standardized is unclear, but the most common weight seems to be 2 kg (4.4 lbs) size with a diameter of approximately 21 cm (8 in), roughly equivalent to the modern discus.[92]

Long jump

In the long jump (halma) competitors swung a pair of weights called halteres. There was no set design; jumpers tended to use either spherical weights made of stone carved to fit the hand or longer lead weights.[93][94] It is debated whether the jump was performed from a standing start or after a run-up. In his analysis of the event based on vase paintings, Hugh Lee concluded that there was probably a short run-up.[95]

Pentathlon

The pentathlon was a competition made up of five events: running, long jump, discus throw, javelin throw, and wrestling.[84] The pentathlon is said to have first appeared at the 18th Olympiad in 708 BC.[96] The competition was held on a single day,[97] but it is not known how the victor was decided,[98][99] or in what order the events occurred,[84] except that it finished with the wrestling.[100]

Equestrian events

Horse racing and chariot racing were the most prestigious competitions in the games, due to only the wealthy being able to afford the maintenance and transportation of horses. These races consisted of different events: the four-horse chariot race, the two-horse chariot race, and the horse with rider race, the rider being hand picked by the owner. The four-horse chariot race was the first equestrian event to feature in the Olympics, being introduced in 680 BC. It consisted of two horses that were harnessed under a yoke in the middle, and two outer horses that were attached with a rope.[101] The two-horse chariot was introduced in 408 BC.[102] The horse with rider competition, on the other hand, was introduced in 648 BC. In this race, Greeks did not use saddles or stirrups (the latter was unknown in Europe until about the 6th century AD), so they required good grip and balance.[103]

Pausanias reports that a race for carts drawn by a pair of mules, and a trotting race, were instituted respectively at the seventieth Festival and the seventy-first, but were both abolished by proclamation at the eighty-fourth. The trotting race was for mares, and in the last part of the course the riders jumped off and ran beside the mares.[104]

The chariot races also saw the first woman to win an Olympic event, as the winner was deemed to be the wealthy benefactor or trainer that funded the team rather than those controlling the chariot (who could only be male). This allowed for horse trainer and spartan princess Cynisca to be the first female Olympic victor.[105]

Due to the winner being the benefactor, it was also possible for a particularly wealthy person to improve their odds by bringing multiple teams to the races; according to Plutarch, the record belongs to Alcibiades, who brought seven chariots to a single competition, winning the first, second, and either the third or fourth place at once.[106]

In 67, the Roman Emperor Nero competed in the chariot race at Olympia. He was thrown from his chariot and was thus unable to finish the race. Nevertheless, he was declared the winner on the basis that he would have won if he had finished the race.[107]

Famous athletes

- Running:

- Koroibos of Elis (stadion, traditionally declared first Olympic champion)

- Orsippus (diaulos, first to compete naked)

- Leonidas of Rhodes (stadion, diaulos and hoplitodromos)

- Chionis of Sparta (three-time stadion/diaulos winner and champion jumper)

- Astylos of Croton (stadion, diaulos and hoplitodromos)

- Alexander I of Macedon (stadion)[108]

- Combat:

- Arrhichion (pankratiast, died while successfully defending his championship in the 54th Olympiad (564 BC). Described as "the most famous of all pankratiasts".)

- Milo of Croton (wrestling, legendary six-time victor: once as youth, the rest in the men's event)

- Diagoras of Rhodes (boxing 79th Olympiad, 464 BC) and his sons Akusilaos and Damagetos (boxing and pankration)

- Timasitheos of Croton (wrestling)[109]

- Theagenes of Thasos (boxer, pankratiast and runner)

- Sostratus of Sicyon (pankratiast, notorious for his finger-breaking technique)

- Dioxippus (pankratiast, crowned champion by default in 336 BC when no other pankratiast dared compete. Such a victory was called akoniti (lit. without getting dusted) and remains the only one ever recorded in the Olympics in this discipline.)

- Varastades (boxing, Prince and future King of Armenia, last known ancient Olympic victor (boxing) during the 291st Olympic Games in the 4th century[110])

- Equestrian:

- Cynisca of Sparta (owner of a four-horse chariot) (first woman to be listed as an Olympic victor)

- Pherenikos ("the most famous racehorse in antiquity", 470s BC)

- Tiberius (steerer of a four-horse chariot)[111]

- Nero (steerer of a ten-horse chariot)

- Other:

- Herodorus of Megara (ten-time trumpet champ)

Olympic festivals in other places

Athletic festivals under the name of "Olympic games", named in imitation of the original festival at Olympia, were established over time in various places all over the Greek world. Some of these are only known to us by inscriptions and coins; but others, as the Olympic festival at Antioch, obtained great celebrity. After these Olympic festivals had been established in several places, the great Olympic festival itself was sometimes designated in inscriptions by the addition of Pisa.[112]

See also

- Archaeological Museum of Olympia

- Epinikion

- Athletes and athletics in ancient Greek art

- Ludi, the Roman games influenced by Greek traditions

- New Testament athletic metaphors

- Olympic Games ceremony

- Panathenaic Games

- History of physical training and fitness

- Tailteann Games (ancient), a similar tradition of legendary pre-Christian Ireland

- Running in Ancient Greece

- Olympic winners of the Stadion race

References

- ^ Ὀλύμπια. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; An Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ "History". Olympic Games. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ^ Tony Parrottet, The Naked Olympics (2004) at 145. Pausinias uses such references frequently in Description of Greece. E.g., "I found that the combat took pace when Pisistratus was archon at Athens in the 4th year . . . of the Olympiad in which Eurybotus, the Athenian, won the footrace." Pausinias, Description of Greece 2.24.7.

- ^ a b Tony Perrottet (8 June 2004). The Naked Olympics: The True Story of the Ancient Games. Random House Digital, Inc. pp. 190–. ISBN 978-1-58836-382-4. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ a b Hamlet, Ingomar. "Theodosius I. And The Olympic Games". Nikephoros 17 (2004): pp. 53–75. See also M.I. Finley & H.W. Pleket, The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years (1976) p. 13.

- ^ Remijsen, Sofie (2015). The End of Greek Athletics in Late Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. p. 49.

- ^ David Sansone, Ancient Greek civilization, Wiley-Blackwell, 2003, p.32

- ^ Mark Golden, Greece & Rome, Second Series, Vol. 58, No. 1 (APRIL 2011) pp. 1–13

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Ancient Olympics". The Perseus Project. Tufts University. Archived from the original on 10 February 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- ^ Kyle, 1999, p.101

- ^ Kyle, 1999, pp.101–102

- ^ Kyle, 1999, p.102–104

- ^ Kyle, 1999, p.102

- ^ Spivey, 2005, pp.225–226

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece, 5.7.6–9

- ^ Spivey, 2005, p.226

- ^ Young 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Beale 2011, pp. 9–12.

- ^ Young 2004, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Wendy J. Raschke (15 June 1988). Archaeology Of The Olympics: The Olympics & Other Festivals In Antiquity. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-0-299-11334-6. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ Beale 2011, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Young 2004, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Beale 2011, p. 12 writes that, while the Bronze Age visual images are typically hard to interpret due to their lack of context and poor condition, Homeric epics provide a detailed description of athletic competitions and the events involved, although, per Young 2004, p. 8, the question is how much of this "is an authentic memory of Mycenaean times, and how much comes from life in eighth-century Greece."

- ^ Early, Gerald (24 January 2019). The Cambridge Companion to Boxing. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-108-65103-5.

- ^ Nelson, Max. (2006) "The First Olympic Games" in Gerald P. Schaus and Stephen R. Wenn, eds. Onward to the Olympics: Historical Perspectives on the Olympic Games (Waterloo), pp. 47–58. See also, for example, "Olympic Games, in The Classical Tradition (2010) p.654.

- ^ a b Sansone 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Young 2004, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Edelman, Edelman (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Sports History. Oxford University Press. p. 85. ISBN 9780199984749.. See also Finley & Pleket, pp.98-99.

- ^ Plutarch, Numa Pompilius 1.4

- ^ Dionysius, 1.74–1–3. Little remains of Eratosthenes' Chronographiae, but its academic influence is clearly demonstrated here in the Roman Antiquities by Dionysius of Halicarnassus.

- ^ Denis Feeney in Caesar's Calendar: Ancient Time and the Beginnings of History. (Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: the University of California Press, 2007), 84.

- ^ "The Athletics of the Ancient Olympics: A Summary and Research Tool" by Kotynski, p.3 (Quote used with permission). For the calculation of the date, see Kotynski footnote 6.

- ^ See, for example, Alfred Mallwitz's article "Cult and Competition Locations at Olympia" p.101 in which he argues that the games may not have started until about 704 BC. Hugh Lee, on the other hand, in his article "The 'First' Olympic Games of 776 B.C.E" p.112, follows an ancient source that claims that there were twenty-seven Olympiads before the first one was recorded in 776. There are no records of Olympic victors extant from earlier than the fifth century BC.

- ^ See Perrott, p.138, and "Olympic Games" in The Oxford Classical Dictionary (2003), p.1066.

- ^ Kyle, Donald (2020). "Ancient Greek and Roman Sport". In Edelman, Robert; Wilson, Wayne (eds.). Oxford Handbook of Sports History. Oxford Univ Press US. pp. 83–86. ISBN 978-0-19-752095-6.

- ^ Spivey, 2005, p.172

- ^ a b Sansone 2004, p. 31.

- ^ "The Ancient Olympic Games". HickokSports. 4 February 2005. Archived from the original on 22 February 2002. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- ^ Finley & Pleket pp. 17, 26, 45–46,

- ^ Perrottet, pp.155–156; Pausinias, Description of Greece 5.6.7 & 6.20.9. For a lengthy examination of the issue, see Matthew Dillon, "Did Parthenoi Attend the Olympic Games? Girls and Women Competing, Spectating, and Carrying Out Cult Roles at Greek Religious Festivals," Hermes vol.128, no. 4 (2000), pp.457–480.

- ^ Dillon (2000), pp.457–458

- ^ a b Young, p. 131

- ^ Newby, Zahra (2005). Greek Athletics in the Roman World: Victory and Virtue. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-19-927930-2.

- ^ Drees, p. 119

- ^ a b Young, p. 132

- ^ Young, p. 133

- ^ Moses of Chorene. History of Armenia. p. 3.40.

- ^ Young, p. 135

- ^ David C. Young (15 April 2008). A Brief History of the Olympic Games. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 135–. ISBN 978-0-470-77775-6. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ "Olympia Hypothesis: Tsunamis Buried the Cult Site On the Peloponnese". Science Daily. 11 July 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ "Altis | ancient site, Greece".

- ^ Wilson; Perseus Archived 11 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Young, p. 134

"A very wealthy Greek, Herodes Atticus, and his very wealthy Roman wife, Regilla, funded an elaborate fountain which was both a practical solution and a work of art. Water, piped in from a tributary of the Alpheus, entered into a large semi-circular basin. Emerging from 83 gargoyle fountains, it was then channeled all around the site. Behind the basin rose a semi-circular colonnade more than 100 feet high, with a series of niches built into its upper level."

- ^ Golden, Mark, p. 77 Archived 4 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Description of Greece 6.13.8

- ^ Stanton, 2000, pp.3–4

- ^ Stanton, 2000, p. 17

- ^ Hansen, 2006, p. 9

- ^ Hansen, 2006, pp.9–10

- ^ Hansen, 2006, p.10

- ^ Hansen, 2006, p.114

- ^ Raschke, 1988, p. 23

- ^ Sansone 2004, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Spivey, 2005, pp.182–183

- ^ a b Swaddling, 1999, p.11

- ^ a b Thucydides (1971). The History of the Peloponnesian War. Vol. 5. Translated by Richard Crawley. The Internet Classics Archive. ISBN 978-0-525-26035-6.

- ^ Strassler & Hanson, 1996, pp. 332–333

- ^ Lendering, Jona. "Peloponnesian War". Livius, Articles on Ancient History. Archived from the original on 13 February 2010.

- ^ Kyle, 2007, p. 8

- ^ Young 2004, pp. 20–21.

- ^ See also "Olympic Games" in The Classical Tradition p.654 and Finley & Peket, p.43.

- ^ Young, p. 18

- ^ Beale 2011, pp. 49, 160.

- ^ "Preparing and organizing the games" Archived 26 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine Foundation of the Hellenic World

- ^ a b Poliakoff, Michael B. (1 January 1987). Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture. Yale University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-300-06312-7.

- ^ See Perrottet, pp.6–7 and "Olympic Games" in The Classical Tradition p.654.

- ^ Pausanias Description of Greece Archived 4 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine 1.44.1. Trans. W. H. S. Jones

- ^ Thucydides (431 BC) The History of the Peloponnesian War Archived 7 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine 1.1 (Trans. R. Crawley)

- ^ Miller, Stephen G. (8 January 2006). Ancient Greek Athletics. Yale University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0300115291. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017 – via Google Books. See also Finley & Pleket, p. 43.

- ^ Miller, Stephen G. (8 January 2006). Ancient Greek Athletics. Yale University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0300115291. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017 – via Google Books. There is uncertainty about this. See, for example, Finley & Pleket, pp.35-37.

- ^ Golden, p. 55. "The dolichos" varied in length from seven to twenty-four lengths of the stadium – from 1,400 to 4,800 Greek feet."

- ^ Miller, p. 32 Archived 15 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine "The sources are not unanimous about the length of this race: some claim that it was twenty laps of the stadium track, others that it was twenty-four. It may have differed from site to site, but it was in the range of 7.5 to 9 kilometers."

- ^ Miller, Stephen G. (8 January 2006). Ancient Greek Athletics. Yale University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-300-11529-1. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gardiner, Edward Norman (15 November 2017). "Greek athletic sports and festivals". London : Macmillan. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Miller, Stephen G. (8 January 2006). Ancient Greek Athletics. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300115291. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ To judge from the story of Damoxenos and Kreugas who boxed at the Nemean Games, after a long battle with no result combatants could agree to a free exchange of hits. (Gardiner, p. 432 Archived 17 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Dunning, Eric (1999). Sport Matters: Sociological Studies of Sport, Violence, and Civilization. Psychology Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-415-06413-2.

- ^ Gardiner, Edward Norman (15 November 2017). "Greek athletic sports and festivals". London: Macmillan. p. 435. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Miller, Stephen G. (8 January 2006). Ancient Greek Athletics. Yale University Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0300115291. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gardiner, p. 445–46 Archived 17 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine "Galen, in his skit on the Olympic games, awards the prize [in the pakration] to the donkey, as the best of all animals in kicking."

- ^ Finley, M. I.; Pleket, H. W. (24 May 2012). The Olympic Games: The First Thousand Years. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486149417. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Miller, p. 60

- ^ Miller, p. 63

- ^ Gardiner, p. 295

- ^ Lee, Hugh M. (2009) "The Halma: A Running or Standing Jump?" Archived 26 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine in Onward to the Olympics: Historical Perspectives on the Olympic Games

- ^ Miller, Stephen G. (8 January 2006). Ancient Greek Athletics. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300115291. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Young, p. 32

- ^ Young, p. 19

- ^ Gardiner, Edward Norman (15 November 2017). "Greek athletic sports and festivals". London: Macmillan. pp. 362–365. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Gardiner, Edward Norman (15 November 2017). "Greek athletic sports and festivals". London: Macmillan. p. 363. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Ancient Olympics". Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017. "Four-horse chariot"

- ^ "Ancient Olympics". Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017. "Two-horse chariot"

- ^ "Ancient Olympics". Archived from the original on 23 October 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2017. "Horse with rider"

- ^ Pausanias, Description of Greece 5.9.1–2 Archived 25 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Millender, Ellen G., "Spartan Women" p. 500–525. In A Companion to Sparta, edited by Anton Powell, Vol. 1 of A Companion to Sparta. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell, 2018.

- ^ Plutarch, The Life of Alcibiades

- ^ "Olympic Games We No Longer Play". 4 August 2016. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ "The History of Herodotus, parallel English/Greek: Book 5: Terpsichore: 20". www.sacred-texts.com. p. 22. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ Young, David C. (15 April 2008). A Brief History of the Olympic Games. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470777756. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ 369 according to Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece by Nigel Wilson, 2006, Routledge (UK) or 385 according to Classical Weekly by Classical Association of the Atlantic States

- ^ Tiberius, AD 1 (or earlier) – cf. Ehrenberg & Jones, Documents Illustrating the Reigns of Augustus and Tiberius [Oxford 1955] p. 73 (n.78)

- ^ William Smith, A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 1875 – ancientlibrary.com Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- Beale, Allan (2011). Greek Athletics and the Olympics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521138208.

- Gardiner, E. N. (1910). Greek athletic sports and festivals. London : Macmillan.

- Gardiner, E. Norman, Athletics of the Ancient World, 246 pages, 200+ illustrations, with new material, Oxford University Press, 1930

- Young, David C. (2004). A Brief History of the Olympic Games (PDF). Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-1130-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2016.

- Miller, Stephen G. (2006). Ancient Greek Athletics. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11529-1.

- Golden, Mark, Sport and Society in Ancient Greece, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Hansen, Mogens Herman (2006). Polis, an Introduction to the Ancient Greek City-State. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920849-4. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- Hanson, Victor Davis; Strassler, Robert B. (1996). The Landmark Thucydides. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-9087-3. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- Kotynski, Edward J. The Athletics of the Ancient Olympics: A Summary and Research Tool. 2006.( 2009-10-25); new link Archived 2 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Kyle, Donald G. (2007). Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22970-4. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- Mallowitz, Alfred. Cult and Competition Locations at Olympia. Raschke 79–109.

- Miller, Stephen. "The Date of Olympic Festivals". Mitteilungen: Des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung. Vol. 90 (1975): 215–237.

- Patay-Horváth, András (2015). The Origins of the Olympic Games. Budapest: Archaeolingua Foundation. ISBN 978-963-9911-72-7.

- Raschke, Wendy J. (1988). The Archaeology of the Olympics: the Olympics and Other Festivals in Antiquity. Madison, Wisconsin: Wisconsin University Press. ISBN 978-0-299-11334-6. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

- Remijsen, Sofie. The End of Greek Athletics in Late Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Sansone, David (2004). Ancient Greek civilization. Wiley. ISBN 9780631232360.

- Spivey, Nigel (2005). The Ancient Olympics. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280433-4. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

origins of the ancient olympics.

- Stanton, Richard (2000). The Forgotten Olympic Art Competitions:The story of the Olympic art competitions of the 20th century. Victoria, Canada: Trafford. ISBN 978-1-55212-606-6. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- Swaddling, Judith (1999). The ancient Olympic Games. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-292-77751-4. Retrieved 12 February 2010.

announcing olympic truce.

- Tufts – "Women and the Games"

- Ancient Olympics. Research by K. U. Leuven and Peking University **Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Christesen, Paul. 2007. Olympic Victor Lists and Ancient Greek History. Cambridge, UK, and New York: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Lee, Hugh M. 2001. The Program and Schedule of the Ancient Olympic Games. Nikephoros Beihefte 6. Hildesheim, Germany: Weidmann.

- Nielsen, Thomas Heine. 2007. Olympia and the Classical Hellenic City-State Culture. Historisk-filosofiske Meddeleser 96. Copenhagen: Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters.

- Sinn, Ulrich. 2000. Olympia: Cult, Sport, and Ancient Festival. Princeton, NJ: M. Wiener.

- Valavanis, Panos. 2004. Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece: Olympia, Delphi, Isthmia, Nemea, Athens. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Swaddling, Judith. 1984. The Ancient Olympic Games. Austin: University of Texas.

External links

- The Ancient Olympic Games virtual museum (requires registration)

- Ancient Olympics: General and detailed information

- The Ancient Olympics: A special exhibit

- The story of the Ancient Olympic Games Archived 1 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- The origin of the Olympics

- Olympia and Macedonia: Games, Gymnasia and Politics. Thomas F. Scanlon, professor of Classics, University of California

- List of Macedonian Olympic winners (in Greek)

- Webquest The ancient and modern Olympic Games

- Goddess Nike and the Olympic Games: Excellence, Glory and Strife

- Ancient Olympic Games: Ancient Events Archived 12 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Storr, Francis (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 443–445.

- The Games Odyssey podcast: The OG Olympic Games, Pt. 1: Ancient Origins

- The Games Odyssey podcast: The OG Olympic Games, Pt. 2: Eternal Glory