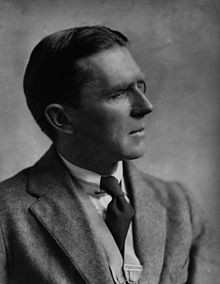

Patrick Abercrombie

Sir Patrick Abercrombie | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Leslie Patrick Abercrombie 6 June 1879 Ashton upon Mersey, Cheshire, England |

| Died | 23 March 1957 (aged 77) Aston Tirrold, Oxfordshire, England |

| Occupation(s) | Architect, Planner, Professor, Theorist. |

| Known for | Creating London |

| Spouse |

Emily Maud Gordon

(m. 1908; died 1942) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | RIBA Royal Gold Medal 1946, AIA Gold Medal 1950 |

| Honours | Knighted in 1945 |

Sir Leslie Patrick Abercrombie FRIBA (/ˈæbərkrʌmbi, -krɒmbi/ AB-ər-krum-bee, -krom-bee;[1] 6 June 1879 – 23 March 1957) was an English architect, urban designer and town planner.[2] Abercrombie was an academic during most of his career, and prepared one city plan and several regional studies prior to the Second World War. He came to prominence in the 1940s for his urban plans of the cities of Plymouth, Hull, Bath, Bournemouth, Hong Kong, Addis Ababa, Cyprus, Edinburgh, Clyde Valley and Greater London.

Early life

Patrick Abercrombie was born in Ashton-upon-Mersey, seventh of nine children of Sarah and William Abercrombie, a stockbroker and businessman who had wide artistic interests, particularly of the Arts and Crafts school. In 1887, the family moved to a new home in Sale, designed by a Leicester architect, Joseph Goddard, with interiors influenced by designer John Aldam Heaton. He spent a year at the Realschule in Lucerne, Switzerland.[3]

Career

In 1897, he was articled to the architect Charles Heathcote, while studying at the Manchester School of Art. After four years, he started work under Arnold Thornely in Liverpool, and set up home in Birkenhead, which remained his home until 1936. After a year working in Chester with architect Philip Lockwood, son of renowned architect T.M Lockwood, in 1907 he was offered a post as junior lecturer and studio instructor at the University of Liverpool School of Architecture. In 1915 year was appointed as Lever Professor of Civic Design at Liverpool, soon becoming a nationally-known authority on town planning and the garden city movement.[4][3] In 1920 he went into partnership with architect Philip Lockwood and F.C. Saxon, as Lockwood Abercrombie and Saxon,[5][6] a firm which still operates in Chester as Lovelock Mitchell, one of the world's oldest architecture firms.

He was later appointed as Professor of Town Planning at University College London, and gradually asserted his dominance as an architect of international renown, which came about through the replanning of Plymouth,[7] Hull, Bath, Edinburgh and Bournemouth, among others. Of his post-war replanning of Plymouth, Sir Simon Jenkins has written:

- Poor Plymouth. It was badly blitzed in the Second World War and then subjected to slash and burn by its city fathers. The modern visitor will find it a maze of concrete blocks, ill-sited towers and ruthless road schemes. Most of this damage was done by one man, Patrick Abercrombie, in the 1950s. The old Barbican district would, in France or Germany, have had its façades restored or rebuilt. Here new buildings were inserted with no feeling for the texture of the old lanes and alleys.[8]

Throughout his life, he devoted his time to civic bodies. He was a founding member of the Town Planning Institute (TPI) formed in 1914 and became its president in 1925.[9] In the 1920s and 1930s, Abercrombie developed a specialty in regional planning. He became chairman of the Council for the Preservation of Rural England in 1926, and was on the Council of the Town and Country Planning Association.[10]

In 1937, he served as President of the Geographical Association. His Presidential Address was entitled 'Geography - the Basis of Planning'.

Greater London planning

He is best known for the post-Second World War replanning of London. In 1943 he created the County of London Plan,[11] and in 1944 the Greater London Plan, together commonly referred to as the Abercrombie Plan.[12] The latter document was an extended and more thorough product than the 1943 publication. Abercrombie conceived the Ringways scheme of London in 1944, proposing four ringroads around Greater London.[13][11]

In 1945 he published A Plan for the City & County of Kingston upon Hull, with the assistance of Sir Edwin Lutyens. Lutyens had died the year before publication whilst much of the plan was being finalised, and the plan was ultimately rejected by the Councillors of Hull.

New towns movement

From the Abercrombie Plan came the New Towns movement[14] which included the building of Harlow and Crawley and the largest 'out-county' estate, Harold Hill in north-east London. He produced the Clyde Valley Regional Plan in 1946 with Robert Matthew that proposed the new towns of East Kilbride and Cumbernauld.[15] In 1949 he published with Richard Nickson a plan for the redevelopment of Warwick, which proposed demolition of almost all the town's Victorian housing stock and construction of a large inner ring road.[16]

International projects

During the postwar years, Abercrombie was commissioned by the British government to redesign Hong Kong, for which he submitted plans in 1947.[17][18] In 1956 he was commissioned by Haile Selassie to draw up plans for the capital of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa; he submitted the plan in 1957 but its major aspects were not carried out.[19]

Awards

Abercrombie was appointed a Knight Bachelor in the 1945 New Year Honours.[20][21][22] He was the most celebrated British planner of his generation.[10] In 1946 he received the RIBA Royal Gold Medal - the highest honour awarded by the Royal Institute of British Architects.[23] In 1948 he became the first president of the newly formed group the International Union of Architects, or the UIA (Union Internationale des Architectes). The group now annually awards the Sir Patrick Abercrombie Prize, for excellence in town planning. In 1950 he received the AIA Gold Medal, the highest architectural honour in America,[24] making him one of the few architects who have won both the prestigious RIBA Gold Medal and AIA Gold Medal, alongside renowned names such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Frank Gehry, Richard Rogers, and Norman Foster.

Legacy

The Abercrombie Building at Oxford Brookes University is home to the Faculty of Technology, Design and Environment.[25] He appears in the film The Proud City presenting his plan to the public.[citation needed]

He died in 1957. A blue plaque has been erected at a house where he lived from 1915 to 1935, on Village Road, Oxton, Merseyside.[26] In July 2023, a blue plaque was erected at a house in Aston Upthorpe, where he lived from 1945 to 1957.[27]

He was the architect of the North East Wales Institute of Higher Education (NEWI) in Wrexham.

Family

Abercrombie married Emily Maud Gordon in 1908; they had one son and one daughter. He was widowed in 1942.[28] Abercrombie was the brother of the poet and critic Lascelles Abercrombie, and uncle to Michael Abercrombie.

Publications

- Patrick Abercrombie, Sydney Kelly and Arthur Kelly, Dublin of the future: the new town plan, being the scheme awarded first prize in the international competition, University Press of Liverpool, Liverpool, 1922.

- Patrick Abercrombie and John Archibald, East Kent Regional Planning Scheme Survey, Kent County Council, Maidstone, 1925.

- Patrick Abercrombie, The Preservation of Rural England, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1926.[29] The book that lead to the foundation of the CPRE.

- The Earl of Mayo, S. D. Adshead and Patrick Abercrombie, The Thames Valley from Cricklade to Staines: A survey of its existing state and some suggestions for its future preservation, University of London Press, London, 1929

- The Earl of Mayo, S. D. Adshead and Patrick Abercrombie, Regional Planning Report on Oxfordshire, Oxford University Press, 1931

- Patrick Abercrombie and Sydney A. Kelly, East Suffolk Regional Scheme, University of Liverpool, Liverpool and Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1935 (prepared for the East Suffolk Joint Regional Planning Committee).

- Patrick Abercrombie (ed), The Book of the Modern House: A Panoramic Survey of Contemporary Domestic Design, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1939

- J. H. Forshaw and Patrick Abercrombie, County of London Plan, Macmillan & Co. 1943.

- J. Paton Watson and Patrick Abercrombie, A Plan for Plymouth, Underhill, (Plymouth). Ltd., 1943.

- Edwin Lutyens & Patrick Abercrombie, A Plan for the City & County of Kingston upon Hull, Brown (London & Hull), 1945.

- Sir Patrick Abercrombie, John Owens & H. Anthony Mealand, A Plan for Bath, Sir Isaac Pitman (London) 1945

- Sir Patrick Abercrombie & R. H. Matthew, Clyde Valley Regional Plan, His Majesty's Stationery Office, Edinburgh, 1946.

- Patrick Abercrombie, Hong Kong Preliminary Planning Report, Government Printer, Hong Kong, 1948.

- Patrick Abercrombie and Richard Nickson, Warwick: Its preservation and redevelopment, Architectural Press, 1949.

- Sir Patrick Abercrombie, Revised by D. Rigby Childs, Town and Country Planning, Third Edition, Oxford University Press, 1959, Reprinted 1961 and 1967.

References

- ^ G.M. Miller, BBC Pronouncing Dictionary of British Names (Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 1.

- ^ Allen, Kate (3 October 2014). "The man who created London – and other urban master planners". Financial Times. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ a b "(Sir) Leslie Patrick Abercrombie". A Biographical Dictionary of the Architects of Greater Manchester, 1800 – 1940. The Victorian Society. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ https://sca-archives.liverpool.ac.uk/Record/13918

- ^ "Obituary for P. H. LOCKWOOD (Aged 74)". Chester Chronicle, and Cheshire and North Wales General Advertiser. 4 February 1939. p. 16. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ "Practice & Values". LMA. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ "RIBA Journal". Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- ^ Jenkins, p. 203

- ^ Yang, Wei (24 January 2024). "Spatial planning reimagined: rekindling the founding spirit for the future". Town Planning Review. 95 (1): 21–44. doi:10.3828/tpr.2023.28 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b Caves, R.W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 1.

- ^ a b Hannikainen, Matti O. (2017). The Greening of London, 1920–2000. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781134807475.

- ^ Abercrombie, Patrick. Greater London Plan, London: University of London Press, 1944.

- ^ Hall, Peter (1982). Great Planning Disasters. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520046023.

- ^ Curl, James Stevens (1999). Oxford Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- ^ Patrick Abercrombie and Robert H. Matthew, The Clyde Valley Regional Plan 1946, a report prepared for the Clyde Valley Regional Planning Committee, Edinburgh, HMS0, 1949

- ^ Patrick Abercrombie and Richard Nickson, WARWICK: Its preservation and redevelopment, Architectural Press, 1949.

- ^ Xue, Charlie Qiuli (2019). Grand Theater Urbanism: Chinese Cities in the 21st Century. Springer. ISBN 9789811378683.

- ^ "Third World Planning Review". 1993.

- ^ "Housing in Ethiopia". 1966.

- ^ Chambers Biographical Dictionary, ISBN 0-550-18022-2, page 4

- ^ "No. 36866". The London Gazette (Supplement). 29 December 1944. p. 1.

- ^ "No. 36943". The London Gazette. 16 February 1945. p. 943.

- ^ "Abercrombie, Leslie Patrick 1879 - 1957 | AHRnet". architecture.arthistoryresearch.net. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ "Gold Medal". www.aia.org. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ "Abercrombie complete — Oxford Brookes University". Archived from the original on 28 June 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ^ "Blue Plaque commemorating Patrick Abercrombie". 24 March 2013.

- ^ "Blue plaque honours the planning pioneer whose name adorns two schools at Oxford Brookes University". 18 July 2023. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ^ "Abercrombie, Sir (Leslie) Patrick, (1879–23 March 1957), Professor Emeritus of Town Planning in the University of London; Hon. Fellow of St Catharine's College, Cambridge; Officer de la Couronne, of Belgium; Member of Royal Commission on the Location of Industry; Chairman of CPRE; CHM. Of Housing Centre; Pres., International Union of Architects; Pres. Franco-British Union of Architects". Who Was Who. 2007. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U233869.

- ^ "Campaign for the Preservation of Rural England (CPRE)". Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

Sources

- Jenkins, Simon (2009). England's Thousand Best Houses. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-103929-9.

External links

- Portraits of Patrick Abercrombie at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- RIBA: Royal Inst. of British Architects

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Patrick Abercrombie

- Department of Civic Design, Liverpool

- Warwick Town History, including description of Abercrombie's 1949 redevelopment plan

- GA Presidential Lecture