Petar Preradović

Petar Preradović | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 19 March 1818 Grabrovnica, Croatian Military Frontier, Austrian Empire |

| Died | 18 August 1872 (aged 54) Fahrafeld, Archduchy of Austria, Austria-Hungary |

| Resting place | Mirogoj, Zagreb, Croatia |

| Occupation | Poet, military officer |

| Language | Croatian[1] |

| Citizenship | Austro-Hungarian |

| Period | Romanticism |

| Genre | Poetry |

| Subject | Patriotism |

| Literary movement | Illyrian movement |

| Children | 8 |

| Relatives | Paula von Preradović (granddaughter) Otto Molden (great-grandson) |

Petar Preradović (Croatian pronunciation: [pětar prerǎːdoʋit͡ɕ]; 19 March 1818 – 18 August 1872) was a Croatian[2][3] poet, writer, and military general. He was one of the most important Croatian poets of the 19th century Illyrian movement and the main representative of romanticism in Croatia.

He was also the paternal grandfather of the Austrian writer and poet Paula Preradović, who is best known for composing the lyrics of the Austrian national anthem.

Early life and education

Petar Preradović was born to a family of Serb origin[4][5] in the village of Grabrovnica near the town of Pitomača in modern-day Croatia, which was a part of the Croatian Military Frontier at the time. He was born to Ivan and Pelagija (née Ivančić) Preradović,[1][6][7] and spent his childhood in his fathers' hometown of Grubišno Polje and Đurđevac.[8] In autobiography Crtice moga života, Preradović wrote of himself as a Croat.[9] He had two sisters, Marija (20 December 1812 – 25 February 1867) and Ana (11 February 1820 – 5 April 1822).[10]

Following his fathers' death in 1828, Preradović, like many from the Military Frontier area, chose to become a professional soldier. He enrolled at the military academy in Bjelovar and later Wiener Neustadt where he converted from Eastern Orthodox Church to Catholicism and went on to excel as one of the school's best students.[11] During the training, all Academy students were conducted as Roman Catholics, which could have been changed at the express request of the soldier.[clarification needed] However, this has rarely occurred. Thus Preradović, tacitly signed as a Roman Catholic convert from the Orthodox Christianity which was legitimized by a formal act of conversion. His loyalty to the Roman Catholic Church was later increased since both he and his wife were Roman Catholics.[12] While at the Academy, he began writing his first poems in German with distinctive features of romanticism.[13]

Career

After graduation, he was stationed in Milan where he met Ivan Kukuljević Sakcinski, a fellow officer from Croatia, who inspired him to start writing in Croatian.[11] This stimulated his interest in Croatian culture and Croatia's political and economic situation. After Milan, Preradović was posted to Zadar where he wrote his first song in Croatian, Poslanica Špiri Dimitroviću (Epistle to Špiro Dimitrović).[14] His writings were published in the local Croatian-language newspaper Zora dalmatinska in 1846.[13] He then went to Zagreb where he met the leading figures of the Illyrian movement. At the request of Ante Kuzmanić, who was then-editor of the Zora dalmatinska, Preradović wrote the song "Zora puca, biche dana" ("Dawn breaks, the day is coming") for the first issue of the paper, published on 1 January 1844. Like most of his songs, this one speaks of the emergence of Croatian national consciousness and suggests a new, prosperous era for the Croatian people.[14][15] Since then, he had systematically continued his poetry in Croatian and has also advocated official acceptance of Ljudevit Gaj's grammar in southern Croatia.[14]

In 1848, he was again stationed in Italy where he took part in the Wars of Italian Unification.[13] In September 1848, he traveled to Dubrovnik, where a month later he married Zadar native Pavica de Ponte. In 1849, he was transferred to Zagreb where he was assigned to the military department of the Ban's Court (Government of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia). In 1851, Ban Josip Jelačić appointed him deputy commander of the military department and Ban's adjutant. At the end of 1852, he moved to Cremona, in 1853 to Verona, in September of that same year to Pančevo, and afterward to Kovin, Arad and Transylvania. In 1854, he was assigned to the Supreme Command in Vienna. In 1855, his wife Pavica committed suicide which sparked his interest in spiritism in his later years. In 1865, he married Emma Regner and was sent to Verona to fight in a war with Italy.[14]

On 24 February 1864, Emperor Franz Joseph I awarded Preradović with the nobility, and also gave him a part of his personal treasury as Preradović was at the time in a bad financial situation. Preradović wrote a song in his honor.[16] In 1866, he became a general.[13] In mid-1871, he participated in the military exercises at Bruck[clarification needed] and was in the same year suggested for the position of Croatian ban, but he was very sick and wrote in a letter that he was not interested.

As his health continued to deteriorate at the end of 1871, he was sent to treatment in Mariabrunn near Munich and then in the Austrian town of Fahrafeld. Petar Preradović died on 18 August 1872 from dropsy. He was buried on 21 August 1872 in Vienna. Viennese youth organization Velebit, proposed that his remains should be transferred to Zagreb. On 11 July 1879, his remains were removed from the Vienna cemetery and transferred to the arcades of Mirogoj cemetery[17] where he was buried on 14 July 1879.[18][19] Mayor of Zagreb August Šenoa held an inspired speech and stirred up the hymn to Preradović, which was inaugurated by Ivan Zajc. The gravestone monument to Petar Preradović, depicting Croatia in a form of a woman that lays flowers on his grave, was made by sculptor Ivan Rendić.[20][21]

He had eight children: Čedomil (8 July 1849 – 24 September 1849), Milica (b. 24 September 1850), Slavica (17 August 1852 – 23 March 1854), Dušan (18 September 1854 – 30 September 1920), Radovan Josip Petar (24 August 1858 – 11 February 1908), Milan (5 February 1866 – 6 August 1879), Zora (13 December 1867 – 10 May 1927) and Jelica (13 June 1870 – 27 December 1870). One of his grandchildren was Paula von Preradović, Austrian poet and the author of the Austrian national anthem.

Lyrical poetry

While attending the military academy in Vienna, Preradović began writing his first poems (Der Brand von Neustadt, 1834) in German. In 1840, he met Ivan Kukuljević Sakcinski, who awoke his interest in Croatian culture and encouraged him to write in his native Croatian. In 1841, in Zagreb's German magazine Croatia he published the song Das Uskoken-Mädchen. On the initiative of Špiro Dmitrović, in 1843, Preradović wrote the first poem in Croatian, Poslanica Špiri Dimitroviću. His first published song written in Croatian Zora puca, bit će dana was published in 1844 in the first issue of Zora dalmatinska.[22] Preradović remained one of the constants of Croatian romanticism by its very nature.[23]

Translator

Preradović translated during schooling the song Máy by Czech poet Karel Hynek Mácha to German. He published in Prevenci his translations of works by Lanau, Scmidt, Lübeck, Gleim, Wieland, Goethe and Bürger. Under Kukuljević's advisement, he translated part of Ivan Gundulić's Osman to German. Preradović translated from French to Croatian Allan Kardec's L’Évangile selon le Spiritisme (Zagreb, 1865).[24] He also translated works by V. J. Pick, George Gordon Byron, Dante Alighieri and Alessandro Manzoni. Preradović translated from Croatian to German Franjo Rački's Rieka prema Hrvatskoj (Fiume gegenüber von Croatien, Dr Franz Rački, Aus dem kroatischen übers von X.Y., Zagreb, 1869). He spoke German, Italian, French, English and almost all Slavic languages.[20]

Works

- Pervenci: različne piesme od P. Preradovića, Zadar, 1846.

- Nove pjesme, Zagreb, 1851.

- Proslov k svečanom otvorenju Narodnoga kazališta dne 29. siječnja 1852. Od P. P. Brzotiskom dra. Ljudevita Gaja., Zagreb, 1852.

- Prvi ljudi, 1862.

- Poesie di Pietro Preradović., Traduzione di Giovanni Nikolić. Tip. Demarchi-Rougier. Zadar, 1866.

- Opera libreto Vladimir i Kosara (in 4 acts)[25]

- Lopudska sirotica[26]

- Pustinjak

Published posthumously

Incomplete list :

- Pjesnička djela Petra Preradovića, Izdana troškom naroda, Zagreb, 1873

- Gedichte / Peter Preradović; treu nach dem Kroatischen übersetzt von H. [Herman] S. [Sommer], Druck von I. Franck , Osijek, 1875

- Izabrane pjesme, Intro by Milivoj Šrepel, Matica hrvatska, Zagreb, 1890

- Izabrane pjesme Petra Preradovića / ed. Franjo Bartuš, Zagreb, 1896

- Básně / Petr Preradović; z chorvatštiny přeložil Frant. Veverka, J. Otto, Prag, 1904

- Život i pjesme Petra Preradovića, ed. Rudolfo Franjin Magjer, Klub hrvatskih književnika Osijek, Osijek, 1916

- Djela Petra Preradovića / ed. Branko Vodnik, volume 2, Zagreb, 1918–1919

- Pesme / Petar Preradović [ed. Andra Žeželj], Beograd, 1940

- Preradovićeva pisma Vatroslavu Bertiću / ed. Ivan Esih, HAZU, Zagreb, 1950

- Izabrane pjesme / Petar Preradović, ed. Dragutin Tadijanović, Matica hrvatska, Zagreb, 1956

- Petar Preradović. Pozdrav domovini: izabrane pjesme, ed. Dragutin Tadijanović, Matica hrvatska, Zagreb, 1968

- Rodu o jeziku / Petar Preradović, ed. Dragutin Tadijanović), Preradovićev muzej u Grabrovnici, Grabrovnica, 1972

- Izabrane pjesme / Petar Preradović,ed. Mirko Tomasović, Erasmus, Zagreb, 1994

- Izabrana djela, ed.Cvjetko Milanja, Matica hrvatska, Zagreb, 1997

- Petar Preradović. Izabrane pjesme, Matica hrvatska, Zagreb, 1999

- Putnik, izabrane pjesme, Kršćanska sadašnjost, Zagreb, 2004

Gallery

-

A statue of Petar Preradović at the Preradović square in Zagreb

-

A view of Preradović square in Zagreb with the Serbian Orthodox Cathedral in the background

-

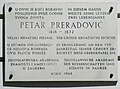

Commemorative Plaque in Vienna

-

The Petar Preradović Library in Bjelovar

See also

References

- ^ a b "Preradović, Petar – Hrvatska enciklopedija". Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ Wachtel, Andrew (1998). Making a Nation, Breaking a Nation: Literature and Cultural Politics in Yugoslavia. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3181-2.

- ^ Furness, Raymond; Humble, Malcolm (1997). A Companion to Twentieth-century German Literature. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-15057-6.

- ^ "Srpsko Narodno Vijeće :: Petar Preradović". snv.hr. Retrieved 2019-12-14.

- ^ "General i pjesnik". portalnovosti.com. Retrieved 2019-12-14.

- ^ "Preradović, Petar – Proleksis enciklopedija". Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ "Preradović, Petar – enciklopedija.lzmk.hr – Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža". Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- ^ Petar Preradović, Milivoj Šrepel, Izabrane pjesme, Izd. Matice hrvatske, Zagreb, 1890., Crtice moga života, p. (I)

- ^ Petar Preradović, Milivoj Šrepel, Izabrane pjesme: uvod napisao Milivoj Šrepel: sa slikom pjesnikovom , Izd. Matice Hrvatske, Zagreb, 1890., p. 3, 16, 366-367

- ^ Petar Preradović. Pozdrav domovini: izabrane pjesme, (izbor i redakcija Dragutin Tadijanović), Matica hrvatska, Zagreb, 1968., p. 203

- ^ a b Fališevac, Dunja; Krešimir Nemec; Darko Novaković (2000). Leksikon hrvatskih pisaca. Zagreb: Školska knjiga d.d. ISBN 953-0-61107-2.

- ^ [Eminent Serbs XIX century, year 2, Volume II, edited by Andra Gavrilovic, Serbian edition printing (deon. Company) in Zagreb. 1903. pp. 14th]

- ^ a b c d biografije.org. "Petar Preradović". Biografije. Archived from the original on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 20 Feb 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Metelgrad – Detalji o Autoru". library.foi.hr. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ "dLib.si – Slovan". www.dlib.si.

- ^ "Život i pjesme Petra Preradovića" (PDF). 1916. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ www.globaldizajn.hr, Globaldizajn. "Gradska groblja Zagreb – P". www.gradskagroblja.hr. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Petar Preradović, Milivoj Šrepel, Izabrane pjesme, Izd. Matice hrvatske, Zagreb, 1890., p. 19

- ^ "Rođen Petar Preradović". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ a b "Petar Preradovic". www.knjiznica-bjelovar.hr. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ "mirogoj". www.hkz-kkv.ch. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Petar Preradović, Milivoj Šrepel, Izabrane pjesme, Izd. Matice hrvatske, Zagreb, 1890., p. 21-22

- ^ Dubravko Jelčić, Povijest hrvatske književnosti, Naklada P.I.P. Pavičić, Zagreb, 2004., II. edition, ISBN 953-6308-56-8, p. 182

- ^ "Katalog Knjižnica grada Zagreba – Detalji". katalog.kgz.hr. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Đuro Šurmin, Povjest književnosti hrvatske i srpske, Tisak i naklada knjižare L. Hartmana, Kugli i Deutsch, 1898., Google Books, p. 182

- ^ Đuro Šurmin, Povjest književnosti hrvatske i srpske, Tisak i naklada knjižare L. Hartmana, Kugli i Deutsch, 1898., Google Books, p. 182-183