Philippine Navy

| Philippine Navy | |

|---|---|

| Hukbong Dagat ng Pilipinas | |

Seal of the Philippine Navy | |

| Founded | May 20, 1898[1] |

| Country | |

| Type | Navy |

| Role | Naval Warfare |

| Size | 24,500 active personnel[2] (including 10,300 Marines)[2] 15,000 reserve personnel[2] 90 combat vessels 16 auxiliary vessels 25 manned aircraft 8 unmanned aircraft |

| Part of | |

| Headquarters | Naval Station Jose Andrada, Roxas Boulevard, Malate, Manila, Philippines |

| Patron | Our Lady of La Naval de Manila |

| Motto(s) | "Protecting the Seas, Securing our Future" |

| Colors | Navy Blue |

| Equipment | List of Philippine Navy equipment |

| Engagements | |

| Website | navy |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-Chief | |

| Secretary of National Defense | |

| Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines | |

| Flag Officer-in-Command of the Philippine Navy | RADM Jose Ma. Ambrosio Q. Ezpeleta, PN |

| Vice Commander of the Philippine Navy | RADM Jose Ma. Ambrosio Q. Ezpeleta, PN |

| Chief of Naval Staff | RADM Alan M. Javier, PN |

| Command Master Chief of the Navy | MCPO Rosimalu D. Galgao, PN |

| Insignia | |

| Ensign and Jack |  |

| Pennant | |

| Flag |  |

| Patch |  |

The Philippine Navy (PN) (Tagalog: Hukbong Dagat ng Pilipinas, lit. 'Army of [the] Sea of [the] Philippines') is the naval warfare service branch of the Armed Forces of the Philippines. It has an estimated strength of 24,500 active service personnel, including the 10,300-strong Philippine Marine Corps.[2] It operates 90 combat vessels, 16 auxiliary vessels, 25 manned aircraft and 8 unmanned aerial vehicles. Tracing its roots from the Philippine Revolutionary Navy on May 20, 1898, while its modern foundations were created during the creation of the Offshore Patrol on February 9, 1939, the PN is currently responsible for naval warfare operations and maritime patrol missions within the Philippine Waters, as well as ensuring the protection of the Philippine's maritime interests, including the South China Sea and Benham Rise.

It shares the responsibility of patrolling the maritime borders with the Philippine Coast Guard, a formerly attached unit which became a separate maritime law enforcement agency in 1998. The PN is also responsible for anti-piracy missions on the Sulu Sea also deploys naval assets during humanitarian assistance operations in the aftermath of disasters.[3] The PN's headquarters is located in Naval Station Jose Andrada in Manila, and is currently led by the Flag Officer-in-Command of the Philippine Navy, who holds the rank of Vice Admiral.

It has two type Commands under it, namely the Philippine Fleet and the Philippine Marine Corps. The Philippine Fleet is responsible in its naval platforms while the Philippine Marine Corps provides it with amphibious forces.

History

Pre-colonial period

Before the Spaniards arrived in the Philippines the ancient native people were already engaging in naval warfare, raiding, trade, piracy, travel and communication using various vessels including balangay.[4] A flotilla of balangay was discovered in the late 1970s in Butuan, Agusan del Norte.[5]

Native Visayan warships, such as the Karakoa or Korkoa, were of excellent quality and some of them were used by the Spaniards in expeditions against rebellious tribes and Dutch and British forces. Some of the larger rowed vessels held up to a hundred rowers on each side besides a contingent of armed troops. Generally, the larger vessels held at least one lantaka at the front of the vessel or another one placed at the stern. Philippine sailing ships called praos had double sails that seemed to rise well over a hundred feet from the surface of the water. Despite their large size, these ships had double outriggers. Some of the larger sailing ships, however, did not have outriggers.[6]

Antecedent to these raids, sometime between A.D. 1174 and 1190, a traveling Chinese government bureaucrat Chau Ju-Kua reported that a certain group of "ferocious raiders of China's Fukien coast" which he called the "Pi-sho-ye," believed to have lived on the southern part of Formosa. In A.D. 1273, another work written by Ma Tuan Lin, which came to the knowledge of non-Chinese readers through a translation made by the Marquis D’Hervey de Saint-Denys, gave reference to the Pi-sho-ye raiders, thought to have originated from the southern portion of Formosa. However, the author observed that these readers spoke a different language and had an entirely different appearance (presumably when compared to the inhabitants of Formosa).

In the Battle of Manila in 1365 is an unspecified and disputed battle occurring somewhere in the vicinity of Manila between the forces of the Kingdoms in Luzon and the Empire of Majapahit.[citation needed]

Even though the exact dates and details of this battle remain in dispute, there are claims of the conquest of the area around Saludong (Majapahit term[citation needed] for Luzon and Manila) according to the text Nagarakretagama[7]

Nevertheless, there may have been a battle for Manila that occurred during that time but it was likely a victory for Luzon's kingdoms considering that the Kingdom of Tondo had maintained its independence and was not enslaved under another ruler. Alternatively, Luzon may have been successfully invaded but was able to regain its independence later.[8][9]

The Luzones people, coming from Luzon and its kingdoms eventually came to become naval powers in Southeast Asia, as Luzones mercenaries where used in wars across Southeast Asia. The former sultan of Malacca decided to retake his city from the Portuguese with a fleet of ships from Lusung in 1525 AD.[10] One famous Luzones was Regimo de Raja, who had been appointed by the Portuguese at Malacca as Temenggung (Jawi: تمڠݢوڠ[11]) or Governor and General. Pires noted that Luzones and Malays (natives of Malacca) had settled in Mjmjam (Perak) and lived in two separate settlements and were "often at variance" or in rivalry with each other.[12]

Pinto noted that there were a number of Luzones in the Islamic fleets that went to battle with the Portuguese in the Philippines during the 16th century. In 1539 Filipinos (Luções) formed part of a Batak-Menangkabau army which besieged Aceh, as well as of the Acehnese fleet which raised the siege under command of Turkish Heredim Mafamede sent out from Suez by his uncle, Suleiman, Viceroy of Cairo. When this fleet later took Aru on the Strait of Malacca, it contained 4,000 Muslims from Turkey, Abyssinia, Malabar, Gujarat and Luzon, and following his victory, Heredim left a hand-picked garrison there under the command of a Filipino by the name of Sapetu Diraja. Sapetu Diraja, was then assigned by the Sultan of Aceh the task of holding Aru (northeast Sumatra) in 1540.

Pinto also says one was named leader of the Malays remaining in the Moluccas Islands after the Portuguese conquest in 1511.[13] Pigafetta notes that one of them was in command of the Brunei fleet in 1521.[citation needed]

However, the Luzones did not only fight on the side of the Muslims. Pinto says they were also apparently among the natives of the Philippines who fought the Muslims in 1538.[13]

On Mainland Southeast Asia, Luzones aided the Burmese king in his invasion of Siam in 1547 AD. At the same time, Luzones fought alongside the Siamese king and faced the same elephant army of the Burmese king in the defence of the Siamese capital at Ayuthaya.[14] Luções military and trade activity reached as far as Sri Lanka in South Asia where Lungshanoid pottery made in Luzon were discovered in burials.[15]

The Battle of Bangkusay, on June 3, 1571, was a naval engagement that marked the last resistance by locals to the Spanish Empire's occupation and colonization of the Pasig River Delta, which had been the site of the indigenous polities of Rajahnate of Maynila and Tondo. Tarik Sulayman, the chief of Macabebes, refused to ally with the Spanish and decided to mount an attack at Bangkusay Channel on Spanish forces, led by Miguel López de Legazpi. Tarik Sulayman's forces were defeated, and Sulayman himself was killed. The Spanish victory in Bangkusay and Legazpi's alliance with Lakandula of Tondo, enabled the Spaniards to establish themselves throughout the city and its neighboring towns.

Spanish period

During the Spanish period, the Spanish forces were entirely responsible for the defense and general order of the archipelago, the Spanish naval forces conducts maritime policing in the seas as well as providing naval logistics to the Army. In the early years of Spanish era, most of the formations of the naval forces were composed of conquistadors backed with native auxiliaries.

Aside from Spanish Navy galleons, brigantines, galleys and other vessels, locally built Manila galleons were among the ships that composed the fleet tasked of protecting the archipelago from foreign and local invaders. Most of the personnel manning the ships are Filipinos while the officers are of Spanish descent.[citation needed]

The Battles of La Naval de Manila were among the earliest naval conflict in the Spanish Philippines. It was a series of five naval battles fought in the waters of the Spanish East Indies in the year 1646, in which the forces of the Spanish Empire repelled various attempts by forces of the Dutch Republic to invade Manila, during the Eighty Years' War. The Spanish forces, consisted of two, and later, three Manila galleons, a galley and four brigantines. They neutralized a Dutch fleet of nineteen warships, divided into three separate squadrons. Heavy damage was inflicted upon the Dutch squadrons by the Spanish forces, forcing the Dutch to abandon their invasion of the Philippines.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, the sailors were already composed of mixed Spanish and Filipino personnel, as well as volunteer battalions composed of all-Filipino volunteers. Filipinos made up a large part of Spain's overseas forces including the Royal Spanish Navy.

Philippine revolution

At the outbreak of the Philippine Revolution, the Filipino members of the Spanish Army and Navy mutinied and switched allegiance from Spain to the Philippines.

The Republic's need for a naval force was first provided for by Filipino revolutionaries when they included a provision in the Biák-na-Bató Constitution. This authorised the government to permit privateers to engage foreign enemy vessels.[16]

(w)hen the necessary army is organized … for the protection of the coasts of the Philippine archipelago and its seas; then a secretary of the navy shall be appointed and the duties of his office added to this Constitution.

— Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo on the Biák-na-Bató Constitution[16]

On May 1, 1898, the first ship handed by Admiral George Dewey to the Revolutionary Navy is a small pinnace from the Reina Cristina of Admiral Patricio Montojo, which was named Magdalo.[16]

The Philippine Navy was established during the second phase of the Philippine Revolution when General Emilio Aguinaldo formed the Revolutionary Navy which was initially composed of a small fleet of eight Spanish steam launches captured from the Spaniards. The ships were refitted with 9-centimeter guns. The rich, namely Leon Apacible, Manuel Lopez and Gliceria Marella de Villavicencio, later donated five other vessels of greater tonnage, the Taaleño, the Balayan, the Bulusan, the Taal and the Purísima Concepción. The 900-ton inter-island tobacco steamer further reinforced the fleet, Compania de Filipinas (renamed as the navy flagship Filipinas), captained by Cuban-Filipino Vicente Catalan who was proclaimed an admiral of the Philippine Navy, this was joined by steam launches purchased from China and other watercraft donated by wealthy patriots.[16][17]

Naval stations were later established to serve as ships' home bases in the following:[17]

- Ports of Aparri

- Ports of Legazpi

- Ports of Balayan

- Ports of Calapan

- Ports of San Roque, Cavite

On September 26, 1898, Aguinaldo appointed Captain Pascual Ledesma (a merchant ship captain) as Director of the Bureau of the Navy, assisted by Captain Angel Pabie (another merchant ship captain). After the passing of the Malolos Constitution the Navy was transferred from the Ministry of Foreign Relations to the Department of War (thereafter known as the Department of War and the Navy) headed by Gen. Mariano Trías.[16][17]

As the tensions between Filipinos and Americans erupted in the 1899 and a blockade on naval forces by the Americans continued, the Philippine naval forces started to be decimated.[16]

American colonial period

The American colonial government in the Philippines created the Bureau of the Coast Guard and Transportation, which aimed to maintain peace and order, transport Philippine Constabulary troops throughout the archipelago, and guard against smuggling and piracy. The Americans employed many Filipino sailors in this bureau and in the Bureaus of Customs and Immigration, Island and Inter-Island Transportation, Coast and Geodetic Survey, and Lighthouses. They also reopened the former Spanish colonial Escuela Nautica de Manila, which was renamed the Philippine Nautical School, adopting the methods of the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis. The U.S. Naval Academy accepted its first Filipino midshipman in 1919, and Filipinos were able to enlist in the U.S. Navy, just as they were formerly able to do in the Spanish Navy.[16]

World War II and Japanese occupation (1941–1945)

In 1935, the Commonwealth Government passed the National Defense Act, which aimed to ensure the security of the country. This was criticized because it placed the burden of the defense of the Philippines on ground forces, which in turn, was formed from reservists. It discounted the need for a Commonwealth air force and navy, and naval protection was provided by the United States Asiatic Fleet.[16]

"A relatively small fleet of such vessels, ...will have distinct effect in compelling any hostile force to approach cautiously and by small detachments."

— Gen. Douglas MacArthur, Military Advisor to the Philippines regarding the newest Offshore Patrol (OSP) PT boats[18]

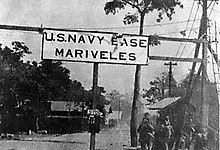

When World War II began, the Philippines had no significant naval forces after the United States withdrew the Asiatic Fleet following the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Imperial Japanese Navy. The Philippines had to rely on its Offshore Patrol (OSP) Force with headquarters located at Muelle Del Codo, Port Area, Manila, composed of five high-speed Thorneycroft Coast Motor Boat (CMB) 55-foot (17 m) and 65-foot (20 m) PT boats, also known as Q-boats, to repel Japanese attacks from the sea.[16][17]

During the course of the war, the OSP were undaunted by the enemy's superiority which they fought with zeal, courage and heroism. For its intrepid and successful missions and raids on enemy ships, the unit was dubbed the "Mosquito Fleet" mainly because of its minuscule size, speed and surprise, it showed its capability to attack with a deadly sting. The unit was cited for gallantry in action when its Q-boats Squadron shot three of nine Japanese dive bombers as they were flying towards shore installations in Bataan.[19] The OSP participated in the evacuation of high Philippine and U.S. government officials from Manila to Corregidor when Manila was declared an open city.[20] Surviving personnel of the Offshore Patrol that didn't surrender after April 9, 1942, to the Japanese, conducted the recognized guerrilla and local military troops of the Philippine Commonwealth Army were hit-and-run attacks against the occupying Japanese forces until the return of U.S. Forces.[16] By the end of the war, 66 percent of its men were awarded the Silver Star Medal and other decorations for gallantry in action.

Post-war period (1945–1992)

Pre-Martial Law administrations (1945-1965)

In 1945, after the liberation of the Philippines, the OSP was reactivated and led by Major Jose Andrada, to reorganize and rebuild from a core of surviving OSP veterans, plus additional recruits. The OSP was strengthened in 1947 after President of the Philippines Manuel Roxas issued Executive Order No. 94. This order elevated the Patrol to a major command that was equal with the Philippine Army, Constabulary, and Air Force. The OSP was renamed the Philippine Naval Patrol, later on changed its name again to the Philippine Navy on January 5, 1951. The first commanding officer of the Navy, Jose Andrada, became its first Commodore and Chief.[16][17] This was also the year when the naval aviation arm of the Navy was formed, now the Naval Air Group.

In 1950, Secretary of Defense Ramon Magsaysay created a marine battalion with which to carry out amphibious attacks against the Communist Hukbalahap movement. The next year, President Elpidio Quirino issued Executive Order No. 389, re-designating the Philippine Naval Patrol as the Philippine Navy. It was to be composed of all naval and marine forces, combat vessels, auxiliary craft, naval aircraft, shore installations, and supporting units that were necessary to carry out all functions of the service.[16]

The Philippine Navy participated in the Korean War, providing Combat Service Support and Escort Operations and in the Vietnam War Transporting the Philippine Contingent In January 1958, the Navy conducted its first US-Philippine naval exercise since the country's 1946 liberation. The exercise was known as Operation "Bulwark One" or Exercise "Bulwark", a harbor defense exercise commanded by a Philippine naval officer. By the 1960s, the Philippine Navy was one of the best-equipped navies in Southeast Asia.

The Ferdinand Marcos administration (1965-1986)

In 1967 during the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos, the maritime law enforcement functions of the Navy were transferred to the Philippine Coast Guard. The duties would stay with the coast guard after 1998 when it became an independent service under the Office of the President and later on the Department of Transportation.[16]

Beginning in the 1970s, the government had to shift its attention towards the Communist insurgency, and this led to the strengthening of the Philippine Army and the Philippine Air Force while naval operations were confined to troop transport, naval gunfire support, and blockade.[16]

One major engagement during this period was the 1974 Battle of Jolo, a confrontation with the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) which ended with the destruction of a large part of the Municipality of Jolo.[21][22] Navy Rear Admiral Romulo Espaldon would later be commended by the municipality for sending naval ships to the Jolo Pier to bring stranded Joloanos to safety, and for playing a big part in the later efforts to rehabilitate Jolo.[23][24]

The Corazon Aquino administration (1986-1992)

The fate of the US military bases in the country was greatly affected by the end of the Cold War, and by the catastrophic eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991 which engulfed the installations with ash and lava flows. The nearby Clark Air Base was eventually abandoned afterwards, while the Philippine Senate voted to reject a new treaty for Subic Naval Complex, its sister American installation in Zambales. This occurrence had effectively ended the century-old US military presence in the country, even as President Corazon Aquino tried to extend the lease agreement by calling for a national referendum. This left a security vacuum in the region and terminated the flow of economic and military aid into the Philippines. [25] [26]

Contemporary period (1992–present)

Concerns about the Chinese incursion to the sea features claimed by the Philippines and other Southeast Asian states were arises after the Chinese construction of a military outpost at the Mischief Reef on 1995. As a response, the Philippine Navy dispatched the BRP Sierra Madre and deliberately ran it aground in the Second Thomas Shoal, 5 miles from the Chinese facility and south of the rumored oil-rich Reed Bank, which it maintains as its own station today.[27][28]

The importance of territorial defense capability was highlighted in the public eye in 1995 when the AFP published photographs of Chinese structures on Mischief Reef in the Spratlys. Initial attempts to improve the capabilities of the armed forces happened when a law was passed in the same year for the sale of redundant military installations and devote 35% of the proceeds for the AFP upgrades. Subsequently, the legislature passed the AFP Modernization Act. The law sought to modernize the AFP over a 15-year period, with minimum appropriation of 10-billion pesos per year for the first five years, subject to increase in subsequent years of the program. The modernization fund was to be separate and distinct from the rest of the AFP budget. The Asian Financial Crisis which struck the region on 1997, greatly affected the AFP Modernization Program due to the government's austerity measures meant to turn the economy around after suffering from losses incurred during the financial crisis.[29]

In 1998, following the closure of US bases, the Philippines-US Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) was signed which contained guidelines for the conduct and protection of American troops visiting the Philippines and stipulated the terms and conditions for the American military to enter Philippine territory. The VFA is a reciprocal agreement that also outlines the requirements for Philippine troops visiting the United States. The Visiting Forces Agreement led to the establishment of the Balikatan exercises, an annual US-Philippine military exercise, as well as a variety of other cooperative measures including the Philippine Bilateral Exercises (PHIBLEX) between the naval forces of the two countries.[30]

The next decade ushered in a cordial relationship between China and its maritime neighbours including the Philippines until 2011 when tensions rose again after consecutive incidents occurred in the disputed territories. In 2012, a Philippine surveillance aircraft identified Chinese fishing vessels at the then Philippine-controlled Scarborough Shoal, causing the Philippine Navy to deploy the BRP Gregorio del Pilar to the area. In response, China sent surveillance ships to warn the Navy to leave the area claimed by both countries, prompting a standoff. The two nations eventually agreed to withdraw their deployed vessels as the arrival of the typhoon season drew near.[31][32] Following a 3-month standoff between Philippine and Chinese vessels around Scarborough Shoal, China informed the Philippines that Chinese coast guard vessels will remain permanently on the shoal as an integral part of their 'Sansha City' in the Woody island of the Paracels, a separate archipelago disputed by China and Vietnam. Under the control of Hainan Province. the Chinese government plans the island-city to have administrative control over a region that encompasses not only the Paracels, but Macclesfield Bank, a largely sunken atoll to the east, and the Spratly Islands to the south.[33]

The incidents with the Chinese presence in the South China Sea prompted the Philippines to proceed with formal measures while challenging the Chinese activities in some of the sea features in the disputed island chain. Hence, the South China Sea Arbitration Case was filed by the Philippines in 2013 at the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS).[34] Reminiscent to what occurred on 1995, the Congress passed the Revised AFP Modernization Act of 2012, this was meant to replace the older AFP Modernization Act of 1995, when the 15-year program expired in 2010. Major naval assets for acquisition under the new AFP modernization program include: 2 frigates, 2 corvettes, 2 strategic sealift vessels (SSV), 6 offshore patrol vessels, missile and other weapon systems upgrade, among others.[35] However, the Navy remains unable to protect other Philippine Reefs that have been claimed by the Chinese.[36] In March 2020, the navy decommissioned four ships, including two vessels that had served with the US Navy in World War II.[37]

Organization

The Philippine Navy is administered through the Department of National Defense (DND). Under the AFP structure, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, AFP, a four-star general/admiral (if the officer is a member of the Philippine Navy), is the most senior military officer. The senior naval officer is the Chief of the Navy, who usually holds the rank of vice admiral. He, along with his or her air force and army counterparts, is junior only to the chairman. The CoN is solely responsible for the administration and operational status of the Navy. His counterpart in the U.S. Navy is the Chief of Naval Operations.[17][38]

Currently, the navy establishment is actually composed of two type commands, the Philippine Fleet and Philippine Marine Corps (PMC). It is further organized into seven naval operational commands, five naval support commands, and seven naval support units.[38] Considering the vastness of the territorial waters that the Navy has to protect and defend, optimal deployment of naval resources is achieved through identification of suitable locations where the presence of these units are capable of delivering responsive services.[17][38]

The Philippine Fleet, or simply the "Fleet", is under the direct command of the Commander, Philippine Fleet while the Marine Corps is answerable to the Commandant, PMC (CPMC). The Chief of the Navy has administrative and operational control over both commands.[17]

Leadership

- Commander-in-Chief: President Bongbong Marcos

- Secretary of National Defense: Secretary Gilberto C. Teodoro

- National Security Adviser: Secretary Eduardo M. Año

- Presidential Adviser for Military Affairs: Secretary Roman A. Felix

- Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines: General Romeo Brawner Jr., PA

- Flag Officer-in-Command of the Philippine Navy: Rear Admiral Jose Ma. Ambrosio Q. Ezpeleta, PN

Type Commands

- Philippine Fleet (PHILFLEET or PF)

- Offshore Combat Force (OCF) - responsible for the overall offshore combat, maritime patrol and territorial defense missions.

- Littoral Combat Force (LCF)- responsible for the overall coastal defense, littoral patrol and interdiction missions.

- Sealift Amphibious Force (SAF) - responsible for the overall naval sealift, amphibious deployment, and transport missions.

- Naval Meteorological and Oceanographic Center (NMOC or NAVMETOC) - responsible for the overall maritime research, hydrographical surveys and meteorological missions.

- Fleet Support Group (FSG) - responsible for the overall fleet support missions.

- Naval Air Wing (NAW) - responsible for overall aerial reconnaissance and maritime patrol operations, as well as air support and future anti-submarine operations.

- Submarine Group (SG) - responsible for future submarine and underwater operations, including training, doctrine development, and overall maritime submarine strategies of the navy.

- Fleet Training and Doctrines Center (FTDC) - responsible for the overall training, education and doctrine development for the newly enlisted and ranked members of the navy.

- Philippine Marine Corps (PMC) - the primary naval infantry, combined arms, and amphibious landing force of the navy.

- Naval Special Operations Command (NAVSOCOM) (formerly the Naval Special Operations Group) - responsible for naval special operations. The unit was recently separated from the Philippine Fleet, and is now a separate command as of 2020.[39]

Naval Air Wing Units

Flying Units:

- 30th Naval Fixed Wing Air Group 30

- 31st Light Utility Patrol Squadron

- 32nd Maritime Patrol & Reconnaissance Squadron

- 40th Naval Helicopter Air Group 40

- 41st Maritime Strike Helicopter Squadron

- 42nd Anti Submarine Helicopter Squadron

- 71st Maritime Unmanned Aerial Reconnaissance Squadron

Non-Flying Units:

- 21st Group Support Squadron

- Naval Air Warfare Training and Doctrine Center

- Aircraft Inspection & Maintenance Squadron

- 62nd Air Combat Systems Squadron

- 63rd Ordnance and Material Supply Squadron

Naval Operational Commands

The Naval Operation Commands are responsible for overall naval and maritime operations, which are divided into seven commands throughout the country, and as follows:[38]

- Naval Forces Northern Luzon (NAVFORNOL)

- Naval Forces Southern Luzon (NAVFORSOL)

- Naval Forces West (NAVFORWEST)

- Naval Forces Central (NAVFORCEN)

- Naval Forces Western Mindanao (NAVFORWESM)

- Naval Forces Eastern Mindanao (NAVFOREASTM)

- Fleet Marine Ready Force

NAVFORWEM and NAVFOREM were formed in August 2006 when Southern Command was split to allow more effective operations against Islamist and Communist rebels within the region.[citation needed]

Naval Support Commands

The Naval Support Commands are responsible for the sustainability of naval and maritime operations, which are divided into five commands, and as follows:[38]

- Naval Sea Systems Command (NSSC)

- Naval Education, Training and Doctrine Command (NETDC)

- Naval Reserve Command (NAVRESCOM)

- Naval Combat Engineer Brigade (NCEBde)

- Naval Installation Command (NIC)

Naval Sea Systems Command

The Naval Sea Systems Command (NSSC), formerly known as Naval Support Command (NASCOM), provides quality and integrated naval system support and services in order to sustain the conduct of naval operations. It is the biggest industrial complex of the Armed Forces of the Philippines. It operates the country's military shipyards, develops new technologies for the Navy, and conducts maintenance on all the Navy's ships. NSSC's principal facilities are at the offshore operating base at Muelle de Codo and at Fort San Felipe in Cavite City.[citation needed]

Naval Education, Training and Doctrine Command

The Naval Education, Training & Doctrine Command (NETDC) is the Philippine Navy's institution of learning. Its mission is to provide education and training to naval personnel so that they may be able to pursue progressive naval careers. NETDC is located in Naval Station Leovigildo Gantioqui, San Antonio, Zambales.[40]

Naval Reserve Command

The Naval Reserve Command (NAVRESCOM) organizes, trains, and administers all naval reservists (which includes the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps Units midshipmen and midshipwomen). It is responsible for recalling reservists to provide the PN the base for expansion to meet sudden spikes in military manpower demand, as for war, rebellion or natural disaster/calamities and to assist in the socio-economic development of the country. The NAVRESCOM is presently based at Fort Santiago, Manila. It was formerly known as the Home Defense Command.[citation needed]

Naval Combat Engineer Brigade

The Naval Combat Engineer Brigade (NCEBde), more popularly known as the Seabees, is tasked with combat engineering and amphibious construction in support of Fleet-Marine operations. Naval combat engineers perform tasks such as mobility, counter-mobility, assault, survivability and construction in the conduct of ground combat and amphibious operations. It executes under combat conditions the construction of roads, bridges and other vital infrastructures; the rehabilitation of piers, harbors and beach facilities; and harbor clearing and salvage works. Alongside the Philippine Marine Corps, the NCEBde is charged with the manning and security of naval garrisons in the contested shoals and islands claimed by the Philippines in the South China Sea. The motto of the Seabees is "We build, We fight!"

Naval Installation Command

The Naval Installation Command (NIC), formerly Naval Base Cavite, provides support services to the Philippine Navy and other AFP tenant units in the base complex, such as refueling, re-watering, shore power connections, berthing, ferry services, tugboat assistance, sludge disposal services and housing.

Naval Support Units

The Naval Support Units are responsible for the overall support of the navy, which includes logistics, personnel, financial, management, civil-military operations, and health care services, which are divided into nine groups and as follows:[38]

- Bonifacio Naval Station

- Civil Military Operations Group-Philippine Navy

- Naval Information and Communication Technology Center

- Fleet-Marine Warfare Center

- Headquarters Philippine Navy & Headquarters Support Group

- Naval Intelligence and Security Force

- Philippine Navy Finance Center

- Naval Logistics Center

- Navy Personnel Management Center

Rank structure

Officers

| Rank group | General / flag officers | Senior officers | Junior officers | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Admiral | Vice admiral | Rear admiral | Commodore | Captain | Commander | Lieutenant commander | Lieutenant | Lieutenant junior grade | Ensign | |||||||||||||||

Enlisted

Equipment

Vessels

The names of commissioned ships of the Philippine Navy are prefixed with the letters "BRP", designating "Barko ng Republika ng Pilipinas" (Ship of the Republic of the Philippines). The names of ships are often selected to honor important people and places. The Philippine Navy is currently operating 90 combat vessels and 16 auxiliary vessels as listed per category below:

Offshore Combatants

Littoral Combatants (coastal-sea defense, marine land-assault boat-operations)

- Missile boats: 10[Nb 2]

- Fast attack craft: 41[Nb 3] (+1)[45]

- Patrol boats: 4[Nb 4] (+4)[46][47]

Amphibious Combatants

- Landing Platforms, Dock: 2 (+2)

- Landing ships, tank / Logistics support vessels: 5

- Landing craft utility: 20

Support Vessels

- Auxiliary ships: 16

- Miscellaneous vessels: 5

Aircraft

The Naval Air Wing has 33 naval air assets consisting of 25 manned aircraft and 8 unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). It prepares and provides these forces for naval operations with assets mainly for maritime reconnaissance and support missions. Its headquarters is located at Danilo Atienza Air Base, Cavite City. It has four units which operate several variants of aircraft:

- 32nd Maritime Patrol and Reconnaissance Squadron (Beechcraft King Air C-90),

- Naval Aviation Squadron MF-30 (BN-2A Islander),

- Naval Aviation Squadron MH-40 (Leonardo AW159 Wildcat, AgustaWestland AW109E Power, and MBB Bo 105C),

- 71st Maritime Unmanned Aerial Reconnaissance Squadron (Boeing Insitu ScanEagle), and

- Naval Air School Center NATS-50 (Cessna Skyhawk 172M and Robinson R22 Beta II).

Logs of Vessels Acquisition

- 2021 Feb 9 : contract signed for 8+1 Shaldag Mk.V orders.[45])

- +2 Cyclone-class fast attack patrol coastal vessels in 2023[48])

- Commissioning 2023[49]

- 2024 Sept 17, two more Acero-class FAICs (hulls 8 & 9) batch-4 were delivered by Israel to the Philippines. They are the 3rd & 4th boats preinstalled with 8 Spike NLOS antiship missiles.[50]

Bases

| Name | Location | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naval Bases | |||

| Naval Base Heracleo Alano (Naval Base Cavite) |

Cavite City | Luzon | Headquarters of the Philippine Fleet |

| Naval Base Camilo Osias (Naval Base San Vicente) |

Santa Ana, Cagayan | Luzon | |

| Naval Base Subic | Subic, Zambales | Luzon | |

| Naval Base Rafael Ramos

(Naval Base Mactan) |

Lapu-Lapu City | Visayas | |

| Naval Station | |||

| Naval Station Jose Andrada (Fort San Antonio Abad) |

Manila | NCR | Headquarters of the Philippine Navy. |

| Naval Station Jose Francisco (Bonifacio Naval Station) |

Taguig | NCR | Part of it was developed as Bonifacio Global City |

| Naval Station Heracleo Alano (Sangley Point) |

Cavite City | Luzon | Headquarters of Naval Air Group |

| Naval Station Pascual Ledesma (Fort San Felipe) |

|||

| Naval Station Ernesto Ogbinar (Naval Station Poro Point) |

San Fernando, La Union | Luzon | Headquarters of Naval Forces Northern Luzon |

| Naval Station Leovigildo Gantioqui (Naval Station San Miguel) |

San Antonio, Zambales | Luzon | Headquarters, Naval Education, Training and Doctrine Command |

| Naval Station Narciso Del Rosario (Naval Station Balabac) |

Balabac Island, Palawan | Luzon | |

| Naval Station Emilio Liwanag (Naval Station Pag-asa) |

Kalayaan Islands, Palawan | Luzon | |

| Naval Station Apolinario Jalandoon (Naval Station Puerto Princesa) |

Puerto Princesa, Palawan | Luzon | |

| Naval Station Carlito Cunanan (Naval Station Ulugan) |

Puerto Princesa, Palawan | Luzon | |

| Naval Station Julhasan Arasain (Naval Station Legazpi) |

Legazpi, Albay | Luzon | Headquarters of Naval Forces Southern Luzon |

| Naval Station Alfonso Palencia (Naval Station Guimaras) |

Guimaras | Visayas | |

| Naval Station Dioscoro Papa (Naval Station Tacloban) |

Tacloban, Leyte | Visayas | |

| Naval Station Felix Apolinario (Naval Station Davao) |

Davao City | Mindanao | Headquarters of Naval Forces Eastern Mindanao |

| Naval Station Romulo Espaldon (Naval Station Zamboanga) |

Zamboanga City | Mindanao | Headquarters of Naval Forces Western Mindanao |

| Naval Station Rio Hondo | Zamboanga City | Mindanao | |

| Naval Station Juan Magluyan (Naval Operating Base Batu-Batu) |

Panglima Sugala, Tawi-Tawi | Mindanao | |

| Marine Bases | |||

| Marine Barracks Rudiardo Brown (Marine Base Manila) |

Taguig | Luzon | Headquarters of the Philippine Marine Corps |

| Marine Barracks Gregorio Lim (Marine Base Ternate) |

Ternate, Cavite | Luzon | Contains the Marine Basic School Campus |

| Marine Barracks Arturo Asuncion (Marine Base Zamboanga) |

Zamboanga City | Mindanao | |

| Marine Barracks Domingo Deluana (Marine Base Tawi-Tawi) |

Tawi-Tawi | Mindanao | |

| Camp Gen. Teodulfo Bautista | Jolo, Sulu | Mindanao | |

Gallery

-

BRP Ramon Alcaraz (PS-16) and BRP Tarlac (LD-601) sail in formation during the at-sea portion of Maritime Training Activity (MTA) Sama Sama 2018.

-

BRP Jose Rizal (FF-150) is the lead ship of her class of guided missile frigates of the Philippine Navy

-

BRP Juan Magluyan (PC 392), a Jose Andrada-class patrol craft.

-

BRP Tarlac (LD-601) is the lead ship of landing platform docks of the Philippine Navy meant for amphibious operations and transport duties

-

BRP Jose Rizal accompanied by a Philippine Navy AW159 Wildcat ASW Helicopter

-

An MPAC Mk. III Missile boat of the Philippine Navy

-

Frigate BRP Antonio Luna (FF-151) of the Philippine Navy

-

BRP Nestor Acero Fast Attack Interdiction Craft

-

Landing craft, BRP Tausug

See also

- Philippine Navy Sea Lions (men's volleyball club)

- Philippine Navy F.C.

Notes

- ^ Frigate official redesignation via their pennant code "FF".

- ^ 4 Acero-class FAIC-M + 6 Mk.3 MPAC. Assault-range SSMs.

- ^ 3 Alvarez-class + 4 Acero-class FAIC (FFBNW SSMs) + 3 Mk.1 MPAC + 3 Mk.2 MPAC + 22 Andrada-class + 2 ex-USN PCF Mk.3 Swift Boats + 4 Type-966Y. FACs are usually 25+ knots. Here, MPAC Mk.2 is the fastest at 45kn / 83kph, while slowest is Andrada-class at 28kn / 52 kph. Their speed also makes them as PBFs (patrol boats fast), chasing armed civilian boats, among other speedy law-enforcement work; and as marine corps fast-transport and fast-response vessels in nearshore and riverine ops.

- ^ 2 Kagitingan-class + 2 Navarette-class (ex-Point-class cutters). They are 21kn and 17kn respectively, used mainly on harbor security, among other non-speed tasks.

References

- Citations

- ^ "PGMA's Speech during the 105th Founding Anniversary of the Philippine Navy". Archived from the original on October 8, 2007. Retrieved June 6, 2008.

- ^ a b c d International Institute for Strategic Studies (February 25, 2021). The Military Balance 2021. London: Routledge. p. 294. ISBN 9781032012278.

- ^ "What is the Balangay?". balangay-voyage.com. Kaya ng Pinoy Inc. Archived from the original on February 27, 2012. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ Roperos, Robert E. (May 28, 2012). "Archeologists to resume excavation of remaining Balangay boats in Butuan". Philippine Information Agency (PIA). Archived from the original on December 21, 2012. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ It was integrated to the Spanish Empire through pacts and treaties (c.1569) by Miguel López de Legazpi and his grandson Juan de Salcedo. During the time of their Hispanization, the principalities of the Confederation have already developed settlements with distinct social structures, cultures, customs, and religions.

- ^ Malkiel-Jirmounsky, Myron (1939). "The Study of The Artistic Antiquities of Dutch India". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 4 (1). Harvard-Yenching Institute: 59–68. doi:10.2307/2717905. JSTOR 2717905.

- ^ Tiongson, Jaime (November 29, 2006). "Pailah is Pila, Laguna". Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2008.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Santos, Hector (October 26, 1996). "The Laguna Copperplate Inscription". Archived from the original on November 21, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ^ Barros, Joao de, Decada terciera de Asia de Ioano de Barros dos feitos que os Portugueses fezarao no descubrimiento dos mares e terras de Oriente [1628], Lisbon, 1777, courtesy of William Henry Scott, Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994, page 194.

- ^ Turnbull, C. M. (1977). A History of Singapore: 1819–1975. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-580354-X.

- ^ The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires: An Account of the East, from the Red Sea to Japan, Volume 2

- ^ a b Pinto, Fernão Mendes (1989) [1578]. The Travels of Mendes Pinto. Translated by Rebecca Catz. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Ibidem, page 195.

- ^ "Quest of the Dragon and Bird Clan; The Golden Age (Volume III)" -Lungshanoid (Glossary)- By Paul Kekai Manansala

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Zulueta, Joselito. "History of the Philippine Navy". Philippine Navy. Archived from the original on February 17, 2010. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "THE PHILIPPINE NAVY" (PDF). dlsu.edu.ph. De La Salle University-Manila (ROTC). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ Morton, Louis. The War in the Pacific: Fall of the Philippines. p.11, 1953. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing House, 1993.

- ^ "Remembering the Battle for Bataan, 1942" Archived March 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Bataan Campaign Website, February 22, 2014, Retrieved February 13, 2016.

- ^ Davis, David, LT, USMC, Page 14, "Introducing: The Philippine Navy" Archived September 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, All Hands: The Bureau of Naval Personnel Career Publication, Number 558, Issue: July 1963, Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ^ Aliman, Agnes (May 8, 2017). "Lesson from '70s Jolo: War and martial law won't solve the problem". Rappler. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ "ARMM gov: Martial Law killings a 'painful part of our history as Moros'". The Philippine Star. September 24, 2018. Archived from the original on September 24, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- ^ Sadain Jr., Said (February 8, 2016). "THAT WE MAY REMEMBER: February 7, 1974: The Jolo-caust". MindaNews. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Tan, Michael L. (May 26, 2017). "From Jolo to Marawi". INQUIRER.net. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- ^ Shenon, Philip (September 16, 1991). "PHILIPPINE SENATE VOTES TO REJECT U.S. BASE RENEWAL". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 19, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "CLOSURE OF U.S. MILITARY BASES IN THE PHILIPPINES: IMPACT AND IMPLICATIONS" (PDF). dtic.mil. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 29, 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ "A Game of Shark and Minnow". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ "Manila Sees China Threat On Coral Reef". The New York Times. February 19, 1995. Archived from the original on March 22, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "Flashback: The AFP's modernization plans in 1995". Philippine Defense Today (Adroth.ph). October 15, 2011. Archived from the original on March 21, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ "Agreement Between the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and the PHILIPPINES" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ "TIMELINE: The Philippines-China maritime dispute". Rappler. July 12, 2016. Archived from the original on March 22, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Perlez, Jane (June 18, 2012). "Philippines and China Ease Tensions in Rift at Sea". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 25, 2024. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ "China to ramp up development on disputed island". Agence France-Presse. Rappler. November 11, 2012. Archived from the original on March 25, 2024. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ McDorman, Ted L. (November 18, 2016). "The South China Sea Arbitration". The American Society of International Law. Archived from the original on March 25, 2024. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ Mogato, Manuel (December 17, 2014). "Philippines to get frigates, gunboats, helicopters as tension simmers". Reuters. Archived from the original on March 25, 2024. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- ^ Mangosing, Frances G. "China military planes land on PH reef". Archived from the original on April 18, 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ Dominguez, Gabriel. "Philippine Navy decommissions two legacy corvettes, two fast attack craft". Janes. Archived from the original on August 12, 2022. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- ^ Philippine Navy Naval Special Operations Command

- ^ "Naval Education and Training Command". netc-navy.edu.ph. Archived from the original on April 22, 2009. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ "Philippines to buy two new South Korean warships for P28B". INQUIRER.net. December 28, 2021. Archived from the original on June 20, 2024. Retrieved December 28, 2021.

- ^ Lee, Daehan (November 24, 2021). "Philippine Navy To Acquire 2nd Pohang-Class Corvette From South Korea". Naval News. Archived from the original on June 11, 2022. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ Nepomuceno, Priam (December 7, 2021). "Gov't allots P62-B for more 'choppers, offshore vessels". Philippine News Agency. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Nepomuceno, Priam (May 14, 2021). "Missile boats to boost PH Navy's capability to defend key waters". Philippine News Agency. Archived from the original on May 14, 2021. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ Valmonte, Kaycee. "US to transfer patrol boats, airplanes to Philippine military". Philstar.com. Archived from the original on May 3, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Nepomuceno, Priam. "4 US patrol boats to beef up PH Navy's defense capabilities". Philippine News Agency. Archived from the original on May 8, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. To Transfer Cyclone-Class Patrol Ships To Philippine Navy". navalnews.com. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ^ Mangosing, Frances (August 2, 2023). "Navy to commission 2 US-donated vessels". INQUIRER.net. Archived from the original on September 8, 2023.

- ^ Nepomuceno, Priam (September 23, 2024). "PH gets 2 more Israeli-made missile boats". Philippine News Agency. Archived from the original on September 23, 2024. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- Bibliography

- Philippine Navy. (1998). Tides of change. Manila: Philippine Navy.

- Philippine Navy. (2007). The Philippine Navy Strategic Sail Plan 2020 Book 1 2007. Manila: Philippine Navy

- Philippine Navy. (2014). "Rough Deck Log: 2014 Philippine Navy Anniversary Issue: To The Shores of Pusan: Combat Service Support and Escort Operations of the Philippine Navy in the Korean War (1950–1953)" by CDR Mark R Condeno