Placename glosses in the Samguk sagi

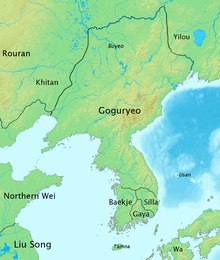

Chapter 37 of the Samguk sagi ('History of the Three Kingdoms', 1145) contains a list of place names and their meanings, from part of central Korea captured by Silla from the former state of Goguryeo (Koguryŏ). Some of the vocabulary extracted from these names provides the principal evidence that Japonic languages were formerly spoken in central and southern parts of the Korean peninsula. Other words resemble Korean or Tungusic words.

Some scholars have ascribed the extracted vocabulary to an Old Koguryŏ language. Others, pointing out that the area concerned had been part of Goguryeo for less than 200 years, argue that these names represent the languages of earlier inhabitants of the area, and call them pseudo-Koguryŏ or Early Paekche (Baekje).

Place name glosses

The Samguk sagi is a history, written in Classical Chinese, of the Korean Three Kingdoms period, which ended in 668. The work was compiled in 1145 from records of the kingdoms of Silla, Goguryeo and Baekje that are no longer extant.[1] Four chapters survey the geography of the former kingdoms. Chapters 34, 35 and 36 describe the territories of Silla, Goguryeo and Baekje respectively. They also cover the administrative re-organization after unification as Later Silla in 668, including former place names and the standardized two-character Sino-Korean names assigned under King Gyeongdeok in the 8th century.[2] Chapter 37, dealing mostly with places in the Goguryeo lands seized by Silla, has a different format, with a series of items of the form

A一云B (A 'one [source] calls' B)

These formulas were first studied by Naitō Konan (1907), Miyazaki Michizaburō (1907) and Shinmura Izuru (1916).[3][4] Substantial analysis began with a series of articles by Lee Ki-Moon in the 1960s, with further contributions by Shichirō Murayama.[5] These scholars interpreted such formulas as giving place names and their meanings.[6] For example, the following entry refers to the city now known as Suwon:[2]

買忽一云水城

Since 水城 is a Chinese phrase meaning 'water city', while 買忽 cannot be read as Chinese, scholars deduce that the characters 買忽 are used to record the sound of the name, while the characters 水城 represent its meaning.[2] From this, they infer that 買 and 忽 represent a local words for 'water' and 'city' respectively.[7] In other cases, the two forms of a name are given in the opposite order or annotated in inconsistent ways. For example, another entry is:

七重縣一云難隱別

In this case, the first part, 七重縣, can be read in Chinese as 'seven-fold county', while 難隱別 is meaningless, and hence seems to represent the sound of the name.[8] From other examples, we infer that 難隱 means 'seven' and 別 means '-fold, layer', while the 'county' part of the gloss is not represented.[9] Such inconsistencies suggest that the names were collated by someone unsure of how they were originally intended to be read.[10]

In this way, a vocabulary of 80 to 100 words has been extracted from these place names.[11][12] Characters like 買 and 忽 presumably represented pronunciations based on some local version of the Chinese reading tradition, but there is no agreement on what this sounded like.[12] Korean scholars tend to use the Sino-Korean readings of 15th century dictionaries of Middle Korean, in which 買 is pronounced may.[13] Another approximation is to use the Middle Chinese reading pronunciations recorded in such dictionaries as the Qieyun (compiled in 601), yielding a pronunciation of mɛ for the same character. In some cases, the same word is represented by several characters with similar pronunciations.[12]

Vocabulary

Several of the words extracted from these names, including all four of the attested numerals, resemble Japonic languages, and are accepted by many authors as evidence that now-extinct Peninsular Japonic languages were once spoken in central and southern parts of the Korean peninsula.[14] Others resemble Korean or Tungusic languages.[15][16]

| Native word | Gloss | Possible cognate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Script | Middle Chinese[a] | Sino-Korean[b] | ||

| 密 | mit | mil | 三 'three' | Old Japanese mi1 'three'[17][18] |

| 于次 | hju-tshijH | wucha | 五 'five' | Old Japanese itu 'five'[17][19] |

| 難隱 | nan-ʔɨnX | nanun | 七 'seven' | Old Japanese nana 'seven'[17][20] |

| 德 | tok | tek | 十 'ten' | Old Japanese to2wo 'ten'[17][21] |

| 旦 | tanH | tan | 谷 'valley' | Old Japanese tani 'valley'[22][23] |

| 頓 | twon | twon | ||

| 吞 | then | thon | ||

| 烏斯含 | ʔu-sje-hom | wosaham | 兎 'rabbit' | Old Japanese usagi1 'rabbit'[24][25] |

| 那勿 | na-mjut | namwul | 鉛 'lead' | Old Japanese namari 'lead'[18][24] |

| 買 | mɛX | may | 川 'river', 水 'water' | Old Japanese mi1(du) 'water'[22][26] |

| 也次 | yæX-tshijH | yacho | 母 'mother' | Middle Korean ezi 'mother, parent'[17][19] |

| 波兮 | pa-hej | phahyey | 巖/峴 'cliff' | Middle Korean pahwoy 'boulder'[17][27] |

| 波衣 | pa-ʔjɨj | phauy | ||

| 巴衣 | pæ-ʔjɨj | phauy | ||

| 別 | pjet | pyel | 重 '-fold, layer' | Middle Korean pol 'pile, layer'[17][28] |

| 首 | syuwH | sywu | 牛 'ox' | Middle Korean sywo 'ox'[17][29] |

| 內米 | nwojH-mejX | naymi | 池 'pool' | Tungusic *namu, *lamu 'lake, sea'[24] |

| 内 | nwojH | nay | 壌 'earth' | Manchu na 'earth'[24] |

| 那 | na | na | ||

| 奴 | nu | no | ||

| 波旦 | pa-tanH | padan | 海 'Sea' | Middle Korean padah /parʌl 'Sea'[30] |

| 古斯 | kuX-sje | kuseul | 玉 'Jade' | Middle Korean kuseul /guseul 'Jade'[30] |

| 加支 | kæ-tsye | kaji | 菁→茄 'Eggplant' | Middle Korean kaji /gaji 'Eggplant'[30] |

| 忽 | xwot | hol | 城 'Castle' | Middle Korean kol /hol 'Castle, City'[30] |

| 達 | dat | dal | 山, 高 'Mountain, High' | Middle Korean tal /dar 'Mountain, high'[30] |

| 皆(次) | keaj(-tshijH) | kesi | 王 'King' | Middle Korean kesi, kuija 'King'[30] |

| 居尸 | kjo-syij | kasi | 心 'Heart, Breast' | Middle Korean kasam, kaseum 'Heart, Breast'[30] |

| 功木 | kuwŋ-muwk | gongmog | 熊 'Bear' | Middle Korean koma, kom, gom 'Bear'[30] |

| 伐力 | bjot-lik | pallyeok | 綠 'Green' | Middle Korean paraha, puru, parak 'Green'[30] |

| 今勿 | kim-mjut | geummul | 黑 'Black' | Middle Korean keom, geom 'Black'[30] |

Interpretations

The first authors to study these words assumed that, because these place names came from the territory of Goguryeo, they must have represented the language of that state.[31] Lee and Ramsey offer the additional argument that the dual use of Chinese characters to represent the sound and meaning of the place names must have been done by scribes of Goguryeo, which would have borrowed written Chinese earlier than the southern kingdoms.[32] They argue that the Goguryeo language formed a link between Japanese and Korean.[33]

Christopher I. Beckwith, assuming that the characters represented a form of northeast Chinese, for which he offers his own reconstruction, claims a much larger proportion of Japonic cognates.[34] Beckwith's linguistic analysis has been criticized for the ad hoc nature of his Chinese reconstructions, for his handling of Japonic material and for hasty rejection of possible cognates in other languages.[35][36]

Other authors point out that most of the place names come from central Korea, an area captured by Goguryeo from Baekje and other states in the 5th century, and none from the historical homeland of Goguryeo north of the Taedong River.[32] These authors suggest that the place names reflect the languages of those states rather than that of Goguryeo.[37] This would explain why they seem to reflect multiple language groups.[38] Kim Bang-han proposes that the place names reflect the original language of the Korean peninsula and a component in the formation of both Korean and Japanese.[39] Toh Soo Hee argues that they reflect the original language of Baekje.[40] Kōno Rokurō argues that two languages were used by different social classes in Baekje, with the glossed placenames coming from the language of the common people.[41]

Notes

- ^ Middle Chinese forms are given using Baxter's transcription for Middle Chinese. The letters H and X denote Middle Chinese tone categories.

- ^ Korean forms are cited using the Yale romanization of Korean.

References

- ^ Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 37.

- ^ a b c Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 37–38.

- ^ Toh (2005), p. 12.

- ^ Beckwith (2004), p. 9.

- ^ Beckwith (2004), p. 10.

- ^ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 37–40.

- ^ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 38–39.

- ^ Unger (2009), p. 73.

- ^ Itabashi (2003), pp. 139, 148.

- ^ Whitman (2013), p. 252.

- ^ Lewin (1976), p. 408.

- ^ a b c Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 39.

- ^ Whitman (2011), p. 154, n. 9.

- ^ Whitman (2011), pp. 153–154.

- ^ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 41, 43.

- ^ Lewin (1973), pp. 24–27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 43.

- ^ a b Itabashi (2003), p. 147.

- ^ a b Itabashi (2003), p. 154.

- ^ Itabashi (2003), p. 148.

- ^ Itabashi (2003), pp. 152–153.

- ^ a b Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 39, 41.

- ^ Itabashi (2003), p. 155.

- ^ a b c d Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 41.

- ^ Itabashi (2003), p. 153.

- ^ Itabashi (2003), p. 146.

- ^ Itabashi (2003), p. 149.

- ^ Itabashi (2003), p. 139.

- ^ Itabashi (2003), p. 151.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lim (2000), pp. 40–64.

- ^ Whitman (2011), p. 154.

- ^ a b Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 40–41.

- ^ Lee & Ramsey (2011), pp. 43–44.

- ^ Beckwith (2004), pp. 252–254.

- ^ Pellard (2005), pp. 168–169.

- ^ Unger (2009), pp. 74–80.

- ^ Lee & Ramsey (2011), p. 40.

- ^ Whitman (2013), pp. 251–252.

- ^ Beckwith (2004), pp. 18–20.

- ^ Toh (2005), pp. 23–26.

- ^ Beckwith (2004), pp. 20–21.

Works cited

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2004), Koguryo, the Language of Japan's Continental Relatives, Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-13949-7.

- Itabashi, Yoshizo (2003), "Kōkuri no chimei kara Kōkurigo to Chōsengo/Nihongo to no shiteki kankei wo saguru" 高句麗の地名から高句麗語と朝鮮語・日本語との史的関係をさぐる [A study of the historical relationship of the Koguryo language, the Old Japanese language, and the Middle Korean language on the basis of fragmentary glosses preserved as place names in the Samguk sagi], in Vovin, Alexander; Osada, Toshiki (eds.), Nihongo keitoron no genzai 日本語系統論の現在 [Perspectives on the Origins of the Japanese Language] (in Japanese), vol. 31, Kyoto: International Center for Japanese Studies, pp. 131–185, doi:10.15055/00005276.

- Lee, Ki-Moon; Ramsey, S. Robert (2011), A History of the Korean Language, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-49448-9.

- Lewin, Bruno (1973), "Japanese and the language of Koguryŏ", Papers of the C.I.C. Far Eastern Languages Institute 4, pp. 19–33.

- ——— (1976), "Japanese and Korean: The Problems and History of a Linguistic Comparison", The Journal of Japanese Studies, 2 (2): 389–412, doi:10.2307/132059, JSTOR 132059.

- Pellard, Thomas (2005), "Koguryo, the Language of Japan's Continental Relatives: An Introduction to the Historical-Comparative Study of the Japanese-Koguryoic Languages with a Preliminary Description of Archaic Northeastern Middle Chinese By Christopher I. Beckwith", Korean Studies, 29: 167–170, doi:10.1353/ks.2006.0008.

- Toh, Soo Hee (2005), "About Early Paekche language mistaken as being Koguryŏ language", Journal of Inner and East Asian Studies, 2 (2): 13–31.

- Unger, J. Marshall (2009), The Role of Contact in the Origins of the Japanese and Korean Languages, Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-3279-7.

- Whitman, John (2011), "Northeast Asian Linguistic Ecology and the Advent of Rice Agriculture in Korea and Japan", Rice, 4 (3–4): 149–158, Bibcode:2011Rice....4..149W, doi:10.1007/s12284-011-9080-0.

- ——— (2013), "A History of the Korean Language, by Ki-Moon Lee and Robert Ramsey", Korean Linguistics, 15 (2): 246–260, doi:10.1075/kl.15.2.05whi.

- Lim, Byungjun, Study on the borrowed writings of the dialect of Koguryo Dynasty in Ancient Korean, by Lim Byung-jun.

Further reading

- Endo, Mitsuaki (2021), "Geographical distribution of certain toponyms in the Samguk Sagi", Anthropological Science, 129 (1): 35–44, doi:10.1537/ase.201229.

- Shinmura, Izuru (1916), "Kokugo oyobi Chōsen-go no sūshi ni tsuite" 國語及び朝鮮語の數詞について [Regarding numerals in Japanese and Korean], Geibun (in Japanese), 7: 2–4.

- Ulman, Vít (2016), "The Language of the Koguryo State: A Critical Reexamination" (PDF), Silva Iaponicarum, 47/48: 64–78, doi:10.14746/sijp.2017.47/48.4.