Pythagorean comma

In musical tuning, the Pythagorean comma (or ditonic comma[a]), named after the ancient mathematician and philosopher Pythagoras, is the small interval (or comma) existing in Pythagorean tuning between two enharmonically equivalent notes such as C and B♯, or D♭ and C♯.[1] It is equal to the frequency ratio (1.5)12⁄27 = 531441⁄524288 ≈ 1.01364, or about 23.46 cents, roughly a quarter of a semitone (in between 75:74 and 74:73[2]). The comma that musical temperaments often "temper" is the Pythagorean comma.[3]

The Pythagorean comma can be also defined as the difference between a Pythagorean apotome and a Pythagorean limma[4] (i.e., between a chromatic and a diatonic semitone, as determined in Pythagorean tuning); the difference between 12 just perfect fifths and seven octaves; or the difference between three Pythagorean ditones and one octave. (This is why the Pythagorean comma is also called a ditonic comma.)

The diminished second, in Pythagorean tuning, is defined as the difference between limma and apotome. It coincides, therefore, with the opposite of a Pythagorean comma, and can be viewed as a descending Pythagorean comma (e.g. from C♯ to D♭), equal to about −23.46 cents.

Derivation

As described in the introduction, the Pythagorean comma may be derived in multiple ways:

- Difference between two enharmonically equivalent notes in a Pythagorean scale, such as C and B♯, or D♭ and C♯ (see below).

- Difference between Pythagorean apotome and Pythagorean limma.

- Difference between 12 just perfect fifths and seven octaves.

- Difference between three Pythagorean ditones (major thirds) and one octave.

A just perfect fifth has a frequency ratio of 3:2. It is used in Pythagorean tuning, together with the octave, as a yardstick to define, with respect to a given initial note, the frequency of any other note.

Apotome and limma are the two kinds of semitones defined in Pythagorean tuning. Namely, the apotome (about 113.69 cents, e.g. from C to C♯) is the chromatic semitone, or augmented unison (A1), while the limma (about 90.23 cents, e.g. from C to D♭) is the diatonic semitone, or minor second (m2).

A ditone (or major third) is an interval formed by two major tones. In Pythagorean tuning, a major tone has a size of about 203.9 cents (frequency ratio 9:8), thus a Pythagorean ditone is about 407.8 cents.

Size

The size of a Pythagorean comma, measured in cents, is

or more exactly, in terms of frequency ratios:

Circle of fifths and enharmonic change

The Pythagorean comma can also be thought of as the discrepancy between 12 justly tuned perfect fifths (ratio 3:2) and seven octaves (ratio 2:1):

|

|

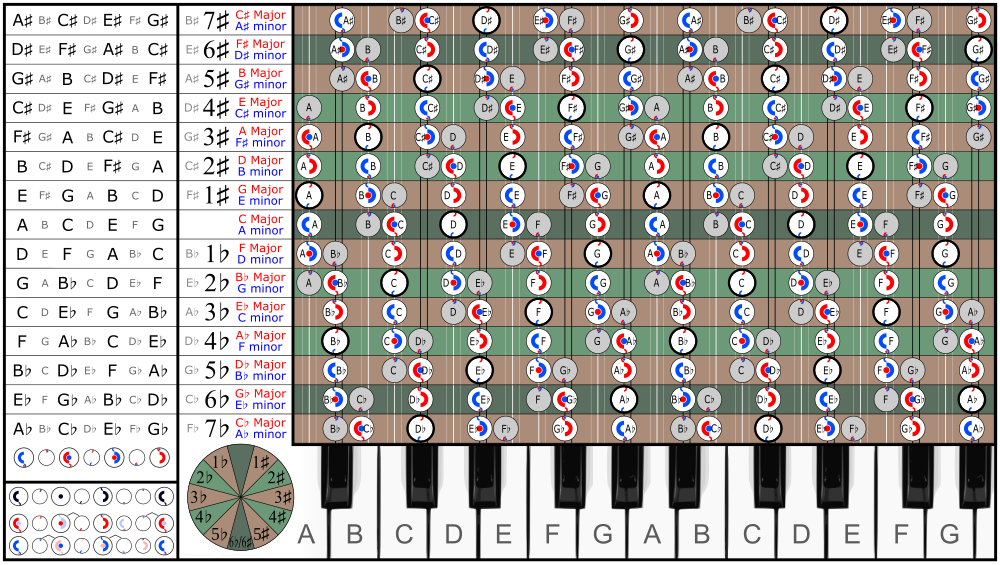

In the following table of musical scales in the circle of fifths, the Pythagorean comma is visible as the small interval between, e.g., F♯ and G♭. Going around the circle of fifths with just intervals results in a comma pump by the Pythagorean comma.

The 6♭ and the 6♯ scales[i] are not identical—even though they are on the piano keyboard—but the ♭ scales are one Pythagorean comma lower. Disregarding this difference leads to enharmonic change.

This interval has serious implications for the various tuning schemes of the chromatic scale, because in Western music, 12 perfect fifths and seven octaves are treated as the same interval. Equal temperament, today the most common tuning system in the West, reconciled this by flattening each fifth by a twelfth of a Pythagorean comma (approximately 2 cents), thus producing perfect octaves.

Another way to express this is that the just fifth has a frequency ratio (compared to the tonic) of 3:2 or 1.5 to 1, whereas the seventh semitone (based on 12 equal logarithmic divisions of an octave) is the seventh power of the twelfth root of two or 1.4983... to 1, which is not quite the same (a difference of about 0.1%). Take the just fifth to the 12th power, then subtract seven octaves, and you get the Pythagorean comma (about a 1.4% difference).

History

The first to mention the comma's proportion of 531441:524288 was Euclid, who takes as a basis the whole tone of Pythagorean tuning with the ratio of 9:8, the octave with the ratio of 2:1, and a number A = 262144. He concludes that raising this number by six whole tones yields a value, G, that is larger than that yielded by raising it by an octave (two times A). He gives G to be 531441.[6] The necessary calculations read:

Calculation of G:

Calculation of the double of A:

Chinese mathematicians were aware of the Pythagorean comma as early as 122 BC (its calculation is detailed in the Huainanzi), and circa 50 BC, Ching Fang discovered that if the cycle of perfect fifths were continued beyond 12 all the way to 53, the difference between this 53rd pitch and the starting pitch would be much smaller than the Pythagorean comma. This much smaller interval was later named Mercator's comma (see: history of 53 equal temperament).

In George Russell's Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization (1953), the half step between the Lydian Tonic and ♭2 in his Altered Major and Minor Auxiliary Diminished Blues scales is theoretically based on the Pythagorean comma.[7]

See also

Notes

- ^ not to be confused with the diatonic comma, better known as syntonic comma, equal to the frequency ratio 81:80, or around 21.51 cents. See: Johnston, Ben (2006). "Maximum Clarity" and Other Writings on Music, edited by Bob Gilmore. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-03098-2.

References

- ^ Apel, Willi (1969). Harvard Dictionary of Music, p. 188. ISBN 978-0-674-37501-7. "...the difference between the two semitones of the Pythagorean scale..."

- ^ Ginsburg, Jekuthiel (2003). Scripta Mathematica, p. 287. ISBN 978-0-7661-3835-3.

- ^ Coyne, Richard (2010). The Tuning of Place: Sociable Spaces and Pervasive Digital Media, p. 45. ISBN 978-0-262-01391-8.

- ^ Kottick, Edward L. (1992). The Harpsichord Owner's Guide, p. 151. ISBN 0-8078-4388-1.

- ^ "Complete Overview of Compositions with Seven Accidentals", Ulrich Reinhardt

- ^ Euclid: Katatome kanonos (lat. Sectio canonis). Engl. transl. in: Andrew Barker (ed.): Greek Musical Writings. Vol. 2: Harmonic and Acoustic Theory, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 190–208, here: p. 199.

- ^ Russell, George (2001) [1953]. George Russell's Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization. Volume One: The art and science of tonal gravity (Fourth (Second printing, corrected, 2008) ed.). Brookline, Massachusetts: Concept Publishing Company. pp. 17, 57–59. ISBN 0-9703739-0-2.