Religion in the Achaemenid era

Religion in the Achaemenid Empire (Persian: دین در دوران هخامنشی ), continues to be a source of debate among academics. The available knowledge about the religious orientation of many of the early Achaemenid kings is incomplete, and the issue of Zoroastrianism of the Achaemenids has been a very controversial issue.

Belief in religions other than Zoroastrianism

Mazdaism religions

It is often thought that the dominant religion of the Achaemenid Empire was Zoroastrianism, but scholars believe that this was not true. For example, 20th-century French linguist Émile Benveniste points out that Ahura Mazda is a very old god and the Zoroastrians used this name to designate the Zoroastrian god. Even the main role assigned to this god in Mazdasim is not a Zoroastrian innovation. The epithet Mazdasene (Mazda worshipper) found in Aramaic papyri from the Achaemenid era cannot be evidence that the Achaemenids were Zoroastrians, and the mention of the name Ahura Mazda in stone inscriptions is not evidence of this either. In the Achaemenid inscriptions, not only is Zoroastrianism not mentioned, but also nothing else is mentioned that could give these inscriptions a Zoroastrian color.[1]

Long before Zoroaster, the Iranians had specific religious beliefs and worshipped Ahura Mazda as a great god.[2] In the Behistun Inscription, Darius only mentions Ahura Mazda as "the greatest of the gods." Ahura Mazda's name appears 69 times in Behistun, and Darius claims to be under Ahura Mazda's protection 34 times. Darius did not claim that Ahura Mazda was the only existing god. Darius also did not mention Ahura Mazda's great rival Angremenu.[3]

Weshparkar

Weshparkar, was the Sogdian god of the Atmosphere and the Wind.[4] He corresponds to the Avestan god Vayu.[5] In Central Asia, Weshparkar has also been associated to the Indian god Shiva.[6]

Anahita

Since the reign of Artaxerxes II the name of the goddess Anahita is mentioned in inscriptions alongside Ahura Mazda and Mitra, and it is mentioned that the palace of Apadana was built at the request of Ahura Mazda, Nahed and Mitra. In this regard, Roman Ghershman writes that Anahita was worshipped by the Achaemenid Ardashir II and by his order, the figure of Anahita was worshipped in the temples of Shush, Iran, Takht-e Jamshid, Hegmatane, Babylon (Dawlatshahr), Damascus and Balkh.[7]

Oxus

The earliest textual evidence of the worship of Oxus, dated to the Achaemenid period, are personal names attested in Aramaic texts from Bactria from the fourth century BCE, such as Vaxšu-bandaka ("slave of Oxus" or "servant of Oxus"), Vaxšu-data ("created by Oxus")[8] and Vaxšu-abra-data ("given by the clouds of Oxus").[9] Further examples occur in Hellenistic sources, for example Oxybazos ("strong through Oxus"), Oxydates ("given by Oxus"), Mithroaxos ("[given by] Mithra and Oxus") and possibly Oxyartes (if the translation "protected by Oxus" is accepted).[10]

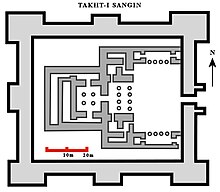

In Takht-i Sangin a temple dedicated to Oxus has been discovered.[11] According to a number of Muslim geographers from the ninth and tenth centuries, this area was customarily considered the beginning of Jayhun (Oxus), which might constitute a survival of an originally Bactrian tradition responsible for the selection of this location as a cult center of the related river god.[12] Excavations indicate that the temple was originally founded in the early Seleucid period, and remained in use until the reign of the Kushan king Huvishka.[13] One of the objects from this site is a stone altar following Greek artistic conventions inscribed with a dedication of a certain Atrosokes to Oxus.[8] His name is Bactrian and can be translated as "burning with sacred fire", and it is possible that he was a priest.[11] Further excavations revealed three more similar Greek inscriptions, seemingly left behind by Bactrian worshipers of Oxus.[14]

A seal with a human-headed bull from the Oxus Treasure is inscribed with Oxus' name written in the Aramaic script.[8] It has been pointed out that the objects found in the temple of Oxus in Takht-i Sangin have close parallels among these belonging to the Oxus Treasure, which might indicate the latter was originally found in the same location.[15] It has been suggested that priests of Oxus hid a number of objects out of fear of looting during a period of increased activity of the Yuezhi in the second half of the second century BCE, but failed to recover them, leaving the Oxus Treasure to only be discovered some two thousand years later.[16]

Other deities

The Persepolis tablets indicate that the royal palace was dedicated in the heart of Persia to the worship of various deities, some of which may have been identified as Iranian (Nariasanga, perhaps Zurvan) and others as Elamite deities still venerated in the same places where they had been for centuries before the arrival of the Persians (Humban, Napirisha).[17][18]

Zoroastrianism in the Achaemenid Empire

Swedish Iranologist Henrik Samuel Nyberg believes that none of the essential characteristics of the Zoroastrian religion can be seen in the basic constructions of the Achaemenid religion.[19]: 372–373 Nyberg writes that there is no clear evidence as to when Zoroastrianism began to spread in Ray, the central base of Mughan. He believes that the latest time for this event was when the Achaemenid state was founded. He considered discussions and opinions on Achaemenid Zoroastrianism to be full of partisan prejudice and superstition among scholars of his time.[19]: 374

Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin wrote: “It seems easier to believe that the Achaemenids had never heard of Zoroaster, nor of his religious reforms".[3] Abdolhossein Zarrinkoob wrote: "In the Achaemenid era, the Magis did not have a Zoroastrian religion, nor did they have a royal family, considering the role that the Mongols played in performing Persian religious ceremonies, and considering that the Achaemenid and dynastic religion could not conflict with the beliefs of the common classes of the Persian clans. It is clear that the Zoroastrian religion had not yet had an influence among the Persians during these periods".[20]

References

- ^ Benveniste, Émile. دین ایرانی بر پایهٔ متنهای مهم یونانی [Iranian Religion: Based on important Greek texts]. Translated by سرکاراتی, بهمن. Tehran: انتشارات بنیاد فرهنگ ایران. pp. 31–36.

- ^ کاشانی. مجموعهٔ سخنرانیهای دومین کنگرهٔ تحقیقات ایرانی [Collection of Lectures of the Second Iranian Research Congress]. p. 224.

- ^ a b Yamauchi, Edwin Masao. ایران و ادیان باستانی [Iran and Ancient Religions]. Translated by Pezez, Manouchehr. Tehran: Atharan Qoqnoos.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (18 April 2018). History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-83860-868-2.

- ^ Li, Xiao (10 September 2020). Studies on the History and Culture Along the Continental Silk Road. Springer Nature. p. 94. ISBN 978-981-15-7602-7.

- ^ Li, Xiao (10 September 2020). Studies on the History and Culture Along the Continental Silk Road. Springer Nature. p. 96. ISBN 978-981-15-7602-7.

- ^ «جلوه های باروری در هنر دوره ساسانی با تاکید بر نقوش ظروف فلزی» (PDF). ۲۰۱۷-۰۳-۱۷. دریافتشده در ۲۰۲۲-۱۱-۱۱.

- ^ a b c Shenkar 2014, p. 128.

- ^ Francfort 2012, p. 129.

- ^ Boyce & Grenet 1991, pp. 179–180.

- ^ a b Litvinskii & Pichikian 1994, p. 57.

- ^ Boyce & Grenet 1991, p. 173.

- ^ Boyce & Grenet 1991, p. 174.

- ^ Shenkar 2014, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Litvinskii & Pichikian 1994, p. 47.

- ^ Litvinskii & Pichikian 1994, p. 55.

- ^ (en) H. Koch, « Theology and Worship in Elam and Achaemenid Iran », dans J. M. Sasson (dir.), Civilizations of the Ancient Near East, New York, 1995, p. 1967-1969

- ^ S. Razmijou, « Religion and Burial Customs », dans Curtis et Tallis (dir.) 2005, p. 150-151.

- ^ a b Nyberg, Henrik Samuel (1359). Religions of ancient Iran. Translated by Najmabadi, Saif al-Din. Tehran: Iranian Center for the Study of Cultures.

- ^ Zarrinkoob, Abdolhossein. تاریخ مردم ایران، ایران قبل از اسلام. pp. 195–196.