Rerum novarum

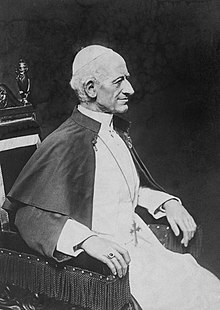

| Rerum novarum Latin for 'of revolutionary change in the world' Encyclical of Pope Leo XIII | |

|---|---|

| |

| Signature date | 15 May 1891 |

| Subject | On capital and labor |

| Number | 38 of 88 of the pontificate |

| Text | |

Rerum novarum (from its incipit, with the direct translation of the Latin meaning "of revolutionary change"[n 1]), or Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor, is an encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII on 15 May 1891. It is an open letter, passed to all Catholic patriarchs, primates, archbishops and bishops, that addressed the condition of the working classes.

It discusses the relationships and mutual duties between labor and capital, as well as government and its citizens. Of primary concern is the need for some amelioration of "the misery and wretchedness pressing so unjustly on the majority of the working class".[5] It supports the rights of labor to form unions, rejects both atheistic socialism and unrestricted capitalism, while affirming the right to private property.

Rerum Novarum is considered a foundational text of modern Catholic social teaching.[6] Many of the positions in Rerum novarum are supplemented by later encyclicals, in particular Pius XI's Quadragesimo anno (1931), John XXIII's Mater et magistra (1961) and John Paul II's Centesimus annus (1991), each of which commemorates an anniversary of the publication of Rerum novarum.

Composition

| Part of a series on |

| Catholic social teaching |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

The first draft and content of the encyclical was written by Tommaso Maria Zigliara, professor from 1870 to 1879 at the College of Saint Thomas (rector after 1873), a member of seven Roman congregations including the Congregation for Studies, and co-founder of the Academia Romano di San Tommaso in 1870. Zigliara's fame as a scholar at the forefront of the Thomist revival was widespread in Rome and elsewhere.[7][8] "Zigliara also helped prepare the great encyclicals Aeterni Patris and Rerum novarum and strongly opposed traditionalism and ontologism in favor of the moderate realism of Aquinas."[9]

The German theologian Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler and the British Cardinal Henry Edward Manning were also influential in its composition.

Message

Rerum novarum is subtitled "On the Conditions of Labor". In this document, Pope Leo XIII articulates the Catholic Church's response to the social conflict in the wake of capitalism and industrialization which had provoked socialist and communist movements and ideologies.

The pope declared that the role of the state is to promote justice through the protection of rights, while the church must speak out on social issues to teach correct social principles and ensure class harmony, calming class conflict. He restated the church's long-standing teaching regarding the crucial importance of private property rights, but recognized, in one of the best-known passages of the encyclical, that the free operation of market forces must be tempered by moral considerations:

Let the working man and the employer make free agreements, and in particular let them agree freely as to the wages; nevertheless, there underlies a dictate of natural justice more imperious and ancient than any bargain between man and man, namely, that wages ought not to be insufficient to support a frugal and well-behaved wage-earner. If through necessity or fear of a worse evil the workman accept harder conditions because an employer or contractor will afford him no better, he is made the victim of force and injustice.[10]

Rerum novarum is remarkable for its vivid depiction of the plight of the nineteenth-century urban poor and for its condemnation of unrestricted capitalism. Among the remedies it prescribes are the formation of trade unions and the introduction of collective bargaining, particularly as an alternative to state intervention.

Although the encyclical follows traditional teaching concerning the rights and duties of property and the relations of employer and employee, it applies the old doctrines specifically to modern conditions (hence the title).[11] Leo first quotes Thomas Aquinas in affirming that private property is a fundamental principle of natural law. He then quotes Gregory the Great regarding its proper use: "He that hath a talent, let him see that he hide it not; he that hath abundance, let him quicken himself to mercy and generosity; he that hath art and skill, let him do his best to share the use and the utility hereof with his neighbor."[12] Liberalism also affirms the right to private property, but communism greatly restricts or eliminates this right.

Rerum novarum also recognizes the special status of the poor in relation to social issues, expressing God's compassion and favor for them: this is elaborated in the modern Catholic principle of the "preferential option for the poor".[13]

Criticism of Socialism

Pope Leo XIII saw socialism as fundamentally flawed, seeking to replace rights and Catholic moral teaching with the ideology of state power. He believed that this would lead to the destruction of the family unit, where moral, productive individuals were taught and raised most successfully.[14]

In the encyclical, the Pope says:

4. To remedy these wrongs the socialists, working on the poor man's envy of the rich, are striving to do away with private property, and contend that individual possessions should become the common property of all, to be administered by the State or by municipal bodies. They hold that by thus transferring property from private individuals to the community, the present mischievous state of things will be set to rights, inasmuch as each citizen will then get his fair share of whatever there is to enjoy. But their contentions are so clearly powerless to end the controversy that were they carried into effect the working man himself would be among the first to suffer. They are, moreover, emphatically unjust, for they would rob the lawful possessor, distort the functions of the State, and create utter confusion in the community[15]

Rights and duties

To build social harmony, the Pope proposes a framework of reciprocal rights and duties between workers and employers. Some of the duties of workers are:

- "fully and faithfully" to perform their agreed-upon tasks

- individually, to refrain from vandalism or personal violence

- collectively, to refrain from rioting and insurrection

Some of the duties of employers are:

- to provide work suited to each person's strength, gender, and age

- to respect the dignity of workers and not treat them as bondsmen

By reminding workers and employers of their rights and duties, the church can form and awaken their conscience. However, the pope also recommended that civil authorities act to protect workers' rights and to keep the peace. The law should intervene no further than necessary to stop abuses.[16] In many cases, governments had acted solely to support the interests of businesses, while suppressing workers unions attempting to bargain for better working conditions.

Principles

The encyclical mentions several fundamental principles to guide relationships between capital and labor.

Dignity of the person

Leo states that "...according to natural reason and Christian philosophy, working for gain is creditable, not shameful, to a man, since it enables him to earn an honorable livelihood."[17] He asserts that God has given human dignity to each person, creating them in God's image and endowing them with free will and immortal souls.[18]

To respect their workers' dignity in the workplace, employers should:

- give time off from work to worship God, and to fulfill family obligations;

- give periods of rest, not expecting work for long hours that preclude adequate sleep;

- not require work under unsafe conditions with danger of bodily harm;

- not require work under immoral conditions that endanger the soul;

- pay a fair daily wage, for which employees should give a full day's work.[18]

The pope specifically mentions work in the mines, and outdoor work in certain seasons, as dangerous to health and requiring additional protections. He condemns the use of child labor as interfering with education and the development of children.

Fair wages are defined in Rerum novarum as at least a living wage, but Leo recommends paying enough to support the worker, his wife and family, with a little savings left over for the worker to improve his condition over time.[19] He also prefers that women work at home.[20]

Common good

Without recommending one form of government over another, Pope Leo puts forth principles for the appropriate role of the state. The primary purpose of a state is to provide for the common good. All people have equal dignity regardless of social class, and a good government protects the rights and cares for the needs of all its members, rich and poor. Everyone can contribute to the common good in some important way.

Leo asserts no one should be forced to share his goods; however, when one is blessed with material wealth, one has a duty to use this to benefit as many others as possible. The Catechism of the Catholic Church lists three principal aspects of the common good: 1) respect for the human person and his rights; 2) social well-being and development; and 3) peace, "the stability and security of a just order."[21]

Subsidiarity

Pope Leo strongly criticizes socialism for seeking to replace the rights and duties of parents, families and communities with the central supervision of the state. The civil government should not intrude into the family, the basic building block of society. However, if a family finds itself in exceeding distress due to illness, injury, or natural disaster, this extreme necessity should be met with public aid, since each family is a part of the commonwealth. By the same token, if there occur a grave disturbance of mutual rights within a household, public authority should intervene to give each party its proper due. Authorities should only intervene when a family or community is unable or unwilling to fulfill its mutual rights and duties.[18]

Rights and duties of property ownership

Private ownership, as we have seen, is the natural right of man, and to exercise that right, especially as members of society, is not only lawful, but absolutely necessary. "It is lawful," says St. Thomas Aquinas, "for a man to hold private property; and it is also necessary for the carrying on of human existence."[22]

Whoever has received from the divine bounty a large share of temporal blessings, whether they be external and material, or gifts of the mind, has received them for the purpose of using them for the perfecting of his own nature, and, at the same time, that he may employ them, as the steward of God's providence, for the benefit of others.[22]

Preferential option for the poor

Leo emphasizes the dignity of the poor and working classes.

As for those who possess not the gifts of fortune, they are taught by the Church that in God's sight poverty is no disgrace, and that there is nothing to be ashamed of in earning their bread by labor.[23]

God Himself seems to incline rather to those who suffer misfortune; for Jesus Christ calls the poor "blessed"; (Matt.5:3) He lovingly invites those in labor and grief to come to Him for solace; (Matt. 11:28) and He displays the tenderest charity toward the lowly and the oppressed.[24]

The richer class have many ways of shielding themselves, and stand less in need of help from the State; whereas the mass of the poor have no resources of their own to fall back upon, and must chiefly depend upon the assistance of the State. And it is for this reason that wage-earners, since they mostly belong in the mass of the needy, should be specially cared for and protected by the government.[25]

This principle of the preferential option for the poor, however, does not appear in Rerum Novarum and was developed more fully, in radically different ways, by later theologians and popes.

This phrase, "option for the poor," is not without its controversy within contemporary CST. Although regularly used today, the phrase came into common use only in the 1970s, largely among Latin American Liberation Theologians, and has accrued little papal rearticulation within the encyclical tradition. In 1968, in response to Paul VI's Populorum Progessio, the Latin American bishops met in Medellín, Colombia, and issued a series of documents condemning "structural injustice" (e.g. 1:2, 2:16, 10:2, and 15:1), calling for a "struggle for liberation," and insisting that "in many instances Latin America finds itself faced with a situation of injustice that can be called institutional violence" (2:16). The bishops in Medellín then insist on giving "effective preference to the poorest and most needy sectors of society," thus giving the first voice to what is now concretized as "the preferential option for the poor." Here, "at Medellín in 1968 the Latin American bishops took the single most decisive step toward an 'option for the poor."[26]

Right of association

Leo distinguished the larger, civil society (the commonwealth, public society), and smaller, private societies within it. Civil society exists to protect the common good and preserve the rights of all equally. Private societies serve various special purposes within civil society. Trade unions are one type of private society, and a special focus of the encyclical: "The most important of all are workingmen's unions, for these virtually include all the rest.... [I]t were greatly to be desired that they should become more numerous and more efficient."[27] Other private societies are families, business partnerships, and religious orders.

Leo strongly supported the right of private societies to exist and govern themselves:

Private societies, then, although they exist within the body politic, and are severally part of the commonwealth, cannot nevertheless be absolutely, and as such, prohibited by public authority. For, to enter into a "society" of this kind is the natural right of man; and the State has for its office to protect natural rights, not to destroy them....[28]

The State should watch over these societies of citizens banded together in accordance with their rights, but it should not thrust itself into their peculiar concerns and their organization, for things move and live by the spirit inspiring them, and may be killed by the rough grasp of a hand from without.[29]

Leo supported unions, yet opposed at least some parts of the then emerging labor movement. He urged workers, if their union seemed on the wrong track, to form alternative associations.

Now, there is a good deal of evidence in favor of the opinion that many of these societies are in the hands of secret leaders, and are managed on principles ill-according with Christianity and the public well-being; and that they do their utmost to get within their grasp the whole field of labor, and force working men either to join them or to starve.[30]

He deplored government suppression of religious orders and other Catholic organizations.

Influence and legacy

Rerum novarum has been interpreted as both a criticism of the illusions of socialism[31] and a primer of the Catholic response to the exploitation of workers.[32] The encyclical also contains a proposal for a living wage, although the text does not use this term: “Wages ought not to be insufficient to support a frugal and well-behaved wage-earner.” The U.S. theologian Msgr. John A. Ryan, a trained economist, elaborated the idea in his book A Living Wage (1906).[33]

The Catholic Encyclopedia (1911), states that the document "has inspired a vast Catholic social literature, while many non-Catholics have acclaimed it as one of the most definite and reasonable productions ever written on the subject."[11]

In 2016, the left-wing periodical Jacobin judged that, from a socialist perspective, Rerum novarum was "uncomfortably" situated between laborers and industrialists, and that "it both opened up space for anticapitalist critique and severely restricted its horizons..."[34]

Influence in Portugal

With the regime established in Portugal under António de Oliveira Salazar in the 1930s, many key ideas from the encyclical were incorporated into Portuguese law. The Estado Novo ("New State") promulgated by Salazar accepted the idea of corporatism as an economic model, especially in labor relations. According to historian Howard J. Wiarda, its basic policies were deeply rooted in European Catholic social thought, especially those deriving from Rerum Novarum. Portuguese intellectuals, workers organizations and trade unions and other study groups were everywhere present after 1890 in many Portuguese Republican circles, as well as the conservative circles that produced Salazar. Wiarda concludes that the Catholic social movement was not only powerful in its own right but it also resonated with an older Portuguese political culture which emphasized a natural law tradition, patrimonialism, centralized direction and control, and the natural orders and hierarchies of society.[35]

See also

- Class collaboration

- Corporatism

- Distributism

- Integralism

- List of encyclicals of Pope Leo XIII

- Political Catholicism

Footnotes

- ^ The opening words in Latin are "Rerum novarum semel excitata cupidine",[1] which in the official English translation is rendered "the spirit of revolutionary change".[2][3] Rerum novarum is the genitive case of res novae, which literally means "new things" but idiomatically has meant "political innovations" or "revolution" since at least the days of Cicero.[3][4] John Molony argues that the word "revolution" is misleading in the context, and that a more appropriate rendering of the Latin would be "the burning desire for change".[3]

Sources

- Rerum novarum, official English translation from the Vatican’s official website

- Brady, Bernard V. (2008). Essential Catholic Social Thought. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-57075-756-3.

References

- ^ "Rerum novarum". The Tablet. 77 (2663): 5. 23 May 1891. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ Rerum novarum, p. 1

- ^ a b c Molony, John (2006). "10: Christian social thought; A: Catholic social teaching". In Gilley, Sheridan; Stanley, Brian (eds.). World Christianities c. 1815–c. 1914. Cambridge History of Christianity. Vol. 8. Cambridge University Press. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-0-521-81456-0. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Lewis, Charlton T.; Short, Charles (1879). "novus". A Latin Dictionary. Founded on Andrews' edition of Freund's Latin dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

But, in gen., novae res signifies political innovations, a revolution

- ^ Rerum novarum, §3

- ^ "'Rerum Novarum' (The Condition of Labor), Berkley Center, Georgetown University". Archived from the original on 2016-04-14. Retrieved 2015-03-03.

- ^ McInerny, Ralph (1968). New Themes in Christian Philosophy. Ardent Media. p. 177.

- ^ "Ite ad Thomam: "Go to Thomas!": There Was Thomism Before Aeterni Patris". 30 January 2010. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ^ Ashley, Benedict. "The Age of Compromise (1800s): Revival and Expansion". The Dominicans. Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2013-08-20.

- ^ Rerum novarum, p. 45

- ^ a b Ryan, John Augustine. "Rerum Novarum." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 5 October 2016

- ^ Gregory the Great. Hom. in Evang., 9, n. 7 (PL 76, 1109B)

- ^ The Busy Christian’s Guide to Social Teaching.

- ^ ""Rerum Novarum" and Seven Principles of Catholic Social Doctrine | Barbara Lanari | Ignatius Insight". www.ignatiusinsight.com. Archived from the original on 2021-01-18. Retrieved 2020-09-08.

- ^ "Rerum Novarum (May 15, 1891) | LEO XIII". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- ^ Rerum novarum, p. 36

- ^ Rerum novarum §20

- ^ a b c Lanari, Barbara. "Rerum Novarum and Seven Principles of Catholic Social Doctrine" Archived 2016-10-09 at the Wayback Machine, Homiletic & Pastoral Review, December 2009

- ^ Rerum novarum, p. 46

- ^ Rerum novarum, p. 42

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church, §§1907–1909

- ^ a b Rerum novarum, p. 22

- ^ Rerum novarum, p. 21

- ^ Rerum novarum, p. 24

- ^ Rerum novarum, p. 37

- ^ See Donal Dorr, Option for the Poor: A Hundred Years of Vatican Social Teaching (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1992), 226.

- ^ Rerum novarum, p. 49

- ^ Rerum novarum, p. 51

- ^ Rerum novarum, p. 55

- ^ Rerum novarum, p. 54

- ^ Uzawa, Hirofumi (1993), Baldassarri, Mario; Mundell, Robert (eds.), ""Rerum Novarum" Inverted: Abuses of Socialism and Illusions of Capitalism", Building a New Europe: Volume 2: Eastern Europe’s Transition to a Market Economy, Central Issues in Contemporary Economic Theory and Policy, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 19–31, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-22922-2_1, ISBN 978-1-349-22922-2, retrieved 2020-09-02

- ^ Brady 2008, p. 60.

- ^ Brady 2008, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Puirseil, Niamh (May 2016). "Labour in Name Only". Jacobin. New York: Jacobin Foundation. p. 67. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- ^ Howard J. Wiarda, "The Portuguese Corporative System: Basic Structures and Current Functions." Iberian studies 2#2 1973) pp 73–80, quoting page 74.

Further reading

- Catholic Social Teaching by Anthony Cooney, John, C. Medaille, Patrick Harrington (Editor). ISBN 0-9535077-6-9

- Catholic Social Teaching, 1891–Present: A Historical, Theological, and Ethical Analysis by Charles E. Curran. Georgetown University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-87840-881-9

- A Living Wage by Rev. John A. Ryan. Macmillan, NY, 1906.

- The Condition of Labor. Open letter to Pope Leo XIII Archived 2010-11-13 at the Wayback Machine by Henry George. 1891.

External links

- Full text of Rerum novarum English translation from the Vatican’s official website

- Exposition of Rerum novarum with guided readings – see 4.2. At VPlater Project: online modules on Catholic Social Teaching