Castleshaw Roman fort

| Castleshaw Roman fort | |

|---|---|

A ditch of Castleshaw Roman fort | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Roman fort |

| Town or city | Castleshaw Saddleworth Greater Manchester |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 53°34′59″N 2°00′11″W / 53.583°N 2.003°W |

| Completed | 79 |

Castleshaw Roman fort was a castellum in the Roman province of Britannia. Although there is no evidence to substantiate the claim, it has been suggested that Castleshaw Roman fort is the site of Rigodunum, a Brigantian settlement. The remains of the fort are located on Castle Hill on the eastern side of Castleshaw Valley at the foot of Standedge but overlooking the valley.[1] The hill is on the edge of Castleshaw in Greater Manchester. The fort was constructed in c. AD 79, but fell out of use at some time during the 90s. It was replaced by a smaller fortlet, built in c. 105, around which a civilian settlement grew. It may have served as a logistical and administrative centre, although it was abandoned in the 120s.

The site has been the subject of antiquarian and archaeological investigation since the 18th century, but the civilian settlement lay undiscovered until the 1990s. The fort, fortlet, and civilian settlement are all protected as a Scheduled Ancient Monument,[2] recognising its importance as a "nationally important" archaeological site or historic building, and protecting it against unauthorised change.[3]

Location

The fort and fortlet at Castleshaw are situated on a step of Grindslow shale on the eastern side of Castleshaw Valley below Standedge, part of the Pennine ridge in northern England.[4] From the site there are clear views up and down the valley, although it is overshadowed by higher ground on all sides. It is remote and exposed and lies along the Deva Victrix (Chester) to Eboracum (York) Roman road. The road crosses the Pennines at Standedge where the area dips and narrows, creating a traversable pass which would have been guarded by the Castleshaw fort.[4] The nearest forts are Mamucium (Manchester) 16 miles (26 km) to the west and one at Slack 8 miles (13 km) to the east, both on the line of the Roman road.[5] There was also a small Roman military installation, possibly a fortlet or signal station at Worlow, between Slack and Castleshaw.[5][6] The later fortlet is on the same site as the fort (grid reference SD99880965).[4]

History

Roman

The fort at Castleshaw, constructed from turf and timber, was built around AD 79 and guarded the York to Chester Roman road.[1] Due to the site's protected status as a Scheduled Ancient Monument it has not been possible to excavate the fort, however previous trenches have demonstrated that the fort had two phases to its construction.[7] The location of the fort's granary, stables, the principia (headquarters), the praetorium (commander's tent), and six long narrow buildings which are possibly workshops or storerooms are all known.[7] The fort was small, would probably have been home to around 500 soldiers of an auxiliary cohort,[7] and fell out of use during the mid AD 90s.[1] Rather than allow the defences to fall into potentially hostile hands or be used against Rome, the fort was slighted.

The fort was replaced by a fortlet, also built using turf and timber, in AD 105. Although the fortlet was built on the same site as the fort, it did not use the same foundation trenches.[7] There were two construction phases of the fortlet, the second – dating to c. 120 – featured gates, an oven, a well, a granary, a hypocaust a workshop, barracks, a commanders house, a courtyard building, and possibly a latrine.[8] The barracks were built to accommodate 48 soldiers and even with administrative staff and officers, the garrison of the fortlet would have numbered less than 100.[9] The first phase was laid out along the same lines as the second phase.[8] The fortlet defences – as with most other fortlets – were designed to withstand attacks from brigands or hold off an enemy until reinforcements from the main army could arrive rather than withstand a determined attack.[10] A civilian settlement or vicus grew around the fortlet in the early 2nd century.[9] It probably would have been home to those who benefited from trade with the garrison or hangers on of the soldiers. Since it is unlikely that a garrison of under 100 could have supported a vicus, it has been suggested that the fortlet was a commissary fortlet, one which was the administrative and logistical centre of part of the Roman army.[9][11] With soldiers regularly arriving to collect pay and orders, a vicus could have been supported.[9] The fortlet fell out of use in the mid 120s. The fort and fortlet of Castleshaw were superseded by the neighbouring forts at Manchester and Slack.[12] The vicus was abandoned around the same time as the fortlet fell out of use.[13]

According to Ptolemy, there was a polis called Rigodunum belonging to the Brigantes near the position of Castleshaw.[14] Rigodunum means "royal fort".[15] Although it has been suggested that Castleshaw is the location of the Brigantine settlement, there is no evidence to support this.[14] Stamps on two tegulae, produced at the Roman tilery at Grimescar Wood near Huddersfield, suggest the fortlet was supplied by the Cohors III Bracaraugustanorum from Pannonia, maybe even garrisoned by them at one stage.[16] Similar stamps have been found in the forts at Manchester, Slack, and Ebchester, indicating these forts were linked.[16]

Post-Roman

After being abandoned by the Romans, Castleshaw was rediscovered by antiquarian Thomas Percival in 1752. The remains were in good enough condition for him to draw a plan and he commented that he was "pleased to find a double Roman camp". He also remarked that the Roman road from Manchester running east to the Pennines was "the finest remain of a Roman road in England that I ever saw".[4] The site has suffered damage from ploughing in the 18th and 19th centuries as it is situated in one of the best draining areas of the valley.[4] In 1897, a local antiquarian and poet, Ammon Wrigley, dug several trenches on the site. He did not record the results of his digging and unrecorded digs continued on and off until 1907.[17] In 1907, the site was bought for the purpose of organised excavation and survey which continued from 1907 to 1908 under the supervision of Francis Bruton who had recently been involved with the excavation of Mamucium.[18] The spoil heaps from the 1907–08 dig were never levelled, leaving a series of misleading modern earthworks on the interior of the site.[19]

Under the supervision of the University of Manchester, further excavation was undertaken on the site in 1957–61 and 1963–64.[19] Between 1984 and 1988, Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit undertook excavations and restoration of the site. A group led by Professor Barri Jones – an expert on Roman Britain – was set up to co-ordinate the work.[20] North West Water, then the owners of the site, ensured the area would not be used for agriculture. In an attempt to make the site accessible to the public, the outline of the fort and fortlet was marked out in low mounds and an education centre was set up nearby.[20] The area beyond the fort was investigated for the first time in 1995–96; archaeologists were searching for a civilian settlement or vicus associated with the fort.[21] Surveys revealed a settlement triangular in shape and to the south of the fort.[21] The vicus is listed as a Scheduled Ancient Monument with the fort and fortlet.[22]

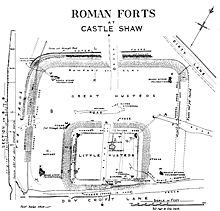

Layout

The fort was rectangular in shape and had sides of 115 metres (377 ft) and 100 metres (330 ft), covering an area of approximately 1.2 hectares (3.0 acres).[1][2] The fortlet was built over the south of the fort, making it difficult to discover what lay beneath.[19] It has been possible, however, to ascertain that barrack buildings lay on the east side of the fort, a granary on the north, and the principia and praetorium to the south west.[7][23]

The fortlet was rectangular, with sides of 50 metres (160 ft) by 40 metres (130 ft), and covered 1,950 square metres (0.48 acres).[1][2] It was originally thought to be surrounded by a single Punic ditch but investigation revealed there to be two Punic ditches separated by a 2 metres (6.6 ft) wide berm.[24] The inner ditch was 3.9 metres (13 ft) wide and 1.3 metres (4.3 ft) deep while the outer ditch was 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) wide and 0.9 metres (3.0 ft) deep.[25] A Punic ditch is a defensive v-shaped ditch with one side much steeper than the other; the ditches surrounding the fortlet had an outer face at 27 degrees and the inner face at 69 degrees.[25] The rampart behind the ditches only survives to 0.5 metres (1.6 ft) at its highest point.[10] It was built from turf on top of sandy clay with a rubble foundation.[10] The fortlet ramparts to the south lay on top of the slighted fort ramparts.[26] Whether corner towers were a feature of the fortlet is unknown, no evidence remains aside from a single posthole, although only the north and east corners survive in good condition.[27] There were two gateways, one to the north and one to the south.[28]

A civilian settlement is located to the south of the fortlet's defences.[29] The extent of the vicus is uncertain,[30] however, test pits have indicated that it probably extends 12 metres (39 ft) west to east and between 25 metres (82 ft) and 35 metres (115 ft) to south.[29]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e Redhead (1999), pp. 74–81.

- ^ a b c Historic England. "Castle Shaw (45891)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- ^ "The Schedule of Monuments". PastScape. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Walker (1989), p. 5.

- ^ a b Walker (1989), p. 15.

- ^ The Romans came this way : the story of the discovery and excavation of a Roman military way across the Yorkshire Pennines. Norman Lunn. Huddersfield: Huddersfield & District Archaeological Society. 2008. pp. 13–19. ISBN 978-0-905747-03-3. OCLC 268619222.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c d e Walker (1989), p. 20.

- ^ a b Walker (1989), p. 21.

- ^ a b c d Redhead (1999), p. 81.

- ^ a b c Walker (1989), p. 25.

- ^ Walker (1989), p. 79.

- ^ Nevell and Redhead (2005), p. 59.

- ^ Brennaud (2006), p. 65.

- ^ a b Walker (1989), p. 13.

- ^ Rivet (1980), p. 18.

- ^ a b Walker (1989), p. 78.

- ^ Walker (1989), pp. 5–6.

- ^ Walker (1989), p. 6.

- ^ a b c Walker (1989), p. 7.

- ^ a b Walker (1989), p. 2.

- ^ a b Redhead (1999), p. 75.

- ^ Historic England. "Monument No. 1130466". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ Walker (1989), p. 18.

- ^ Walker (1989), pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Walker (1989), p. 23.

- ^ Walker (1989), p. 27.

- ^ Walker (1989), p. 28.

- ^ Walker (1989), p. 29.

- ^ a b Redhead (1999), pp. 76–77.

- ^ Redhead (1999), p. 80.

Bibliography

- Brennand, Mark, ed. (2006). The Archaeology of North West England. Council for Archaeology North West. ISSN 0962-4201.

- Nevell, Mike; Redhead, Norman, eds. (2005). Mellor: Living on the Edge. A Regional Study of an Iron Age and Romano-British Upland Settlement. University of Manchester Archaeological Unit, Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit, and the Mellor Archaeological Trust. ISBN 0-9527813-6-0.

- Redhead, Norman 'Extra-Mural Settlement in a Marginal Context: Roman Castleshaw' in Nevell, Mike, ed. (1999). Living on the Edge of Empire: Models, Methodology & Marginality. CBA North West, the Field Archaeology Centre, University of Manchester, and Chester Archaeology. pp. 74–81. ISBN 0-9527813-1-X.

- Rivet, A.L.F. (1980). "Celtic Names and Roman Places". Britannia. 11.

- Walker, John, ed. (1989). Castleshaw: The Archaeology of a Roman Fortlet. Greater Manchester Archaeological Unit. ISBN 0-946126-08-9.