Roman snail

| Helix pomatia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Gastropoda |

| Order: | Stylommatophora |

| Family: | Helicidae |

| Genus: | Helix |

| Species: | H. pomatia

|

| Binomial name | |

| Helix pomatia | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

|

List

| |

Helix pomatia, known as the Roman snail, Burgundy snail, or escargot, is a species of large, air-breathing stylommatophoran land snail native to Europe. It is characterized by a globular brown shell. It is an edible species which commonly occurs synanthropically throughout its range.

Distribution

The present distribution of Helix pomatia is considerably affected by the dispersion by human and synanthropic occurrences. The northern limits of their natural distribution run presumably through central Germany and southern Poland with the eastern range limits running through western-most Ukraine and Moldova/Romania to Bulgaria. In the south, the species reaches northern Bulgaria, central Serbia, Bosnia and Hezegovina and Croatia. It occurs in northern Italy southwards to the Po and the Ligurian Apennines. Westerly the native range extends to eastern France.[4][5] Currently, H. pomatia is distributed up to western Russia (broadly distributed in and around Moskva),[6] to the south of Finland, Sweden and Norway, in Denmark and the Benelux. Scattered introduced populations occur westwards up to northern Spain. In Great Britain, it lives on chalk soils in the south and west of England. In the east, isolated populations live as far as south of Novosibirsk.[6] Introduced populations also exist in the eastern United States and Canada.[7]

Description

The shell is creamy white to light brownish, often with indistinct brown colour bands although sometimes the banding is well developed and conspicuous. The shell has five to six whorls. The aperture is large. The apertural margin is slightly reflected in adult snails. The umbilicus is narrow and partly covered by the reflected columellar margin.[8]

The width of the shell is 30–50 millimetres (1.2–2.0 inches).[8] The height of the shell is 30–45 mm (1.2–1.8 in).[8]

Ecology

Habitat

In Central Europe, it occurs in forests and shrubland, as well as in various synanthropic habitats. It lives up to 2,100 m (6,900 ft) above sea level in the Alps, but usually below 2,000 m (6,600 ft).[8] In the south of England, it is restricted to undisturbed grassy or bushy wastelands, usually not in gardens.[8]

Lifecycle

This snail is hermaphroditic. Reproduction in Central Europe begins at the end of May.[8]

- Reproduction

-

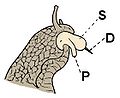

Reproductive system of H. pomatia

-

A pair of H. pomatia in courtship, shortly before mating

-

Drawing of head of mating H. pomatia with everted penis and dart sac shooting a love dart

-

Drawing of H. pomatia laying eggs

Eggs are laid in June and July, in clutches of 40–65 eggs.[8] The size of the egg is 5.5–6.5 mm[8] or 8.6 × 7.2 mm.[9] Juveniles hatch after three to four weeks, and may consume their siblings under unfavourable climate conditions.[8] Maturity is reached after two to five years.[8] The life span is up to 20 years, but they often die sooner due to drying in summer and freezing in winter.[8] Ten-year-old individuals are probably not uncommon in natural populations.[8] The maximum lifespan is 35 years.[8]

During estivation or hibernation, H. pomatia is one of the few species that is capable of creating a calcareous epiphragm to seal the opening of its shell.

- Hibernation

-

Drawing of H. pomatia during hibernation

-

Photo of the shell with an epiphragm

-

Epiphragm of H. pomatia

Preference for feeding on the nettle Urtica dioica was found in H. pomatia juveniles in Germany.[10]

Conservation

This species is listed in IUCN Red List, and in European Red List of Non-marine Molluscs as of least concern.[1][11] H. pomatia is threatened by continuous habitat destructions and drainage, usually less threatened by commercial collections.[8] Many unsuccessful attempts have been made to establish the species in various parts of England, Scotland, and Ireland; it only survived in natural habitats in southern England, and is threatened by intensive farming and habitat destruction.[8] It is of lower concern in Switzerland and Austria, but many regions restrict commercial collecting.[8]

Within its native range, Helix pomatia is mostly a common species. It is also considered Least Concern by the IUCN Red List.[1] However, it is listed in the Annex V of the EU's Habitats Directive and protected by law in several countries to regulate harvesting from free living populations.

- Germany: listed as a specially protected species in annex 1 of the Bundesartenschutzverordnung.

- Austria: the protection is up to Bundesländer,[12] and the species is protected in some (e.g. Burgenland[13]).

- Great Britain: protected in England under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981, making it illegal to kill, injure, collect or sell these snails.[14]

- France: collecting prohibited of individuals with shell diameter under 3 cm and during the period from 1 April to 30 June.[15]

- Denmark: commercial collecting is prohibited.[16]

Uses

The intestinal juice of H. pomatia contains large amounts of aryl, steroid, and glucosinolate sulfatase activities. These sulfatases have a broad specificity, so they are commonly used as a hydrolyzing agent in analytical procedures such as chromatography where they are used to prepare samples for analysis.[17]

Culinary use and history

Roman snails were eaten by Ancient Romans.[18]

Nowadays, these snails are especially popular in French cuisine. In the English language, it is called by the French name escargot when used in cooking (escargot simply means snail).

Although this species is highly prized as a food, it is difficult to cultivate and is rarely farmed commercially.[19]

References

This article incorporates public domain text from the reference.[8]

- ^ a b c Neubert, E. (2011). "Helix pomatia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2011: e.T156519A4957463. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-1.RLTS.T156519A4957463.en. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Linnaeus C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. pp. [1–4], 1–824. Holmiae. (Salvius).

- ^ "Helix pomatia Linnaeus, 1758". Catalogue of Life. Species 2000: Leiden, the Netherlands. Retrieved 14 July 2024.

- ^ Korábek, Ondřej; Petrusek, Adam; Juřičková, Lucie (2018-01-01). "Glacial refugia and postglacial spread of an iconic large European land snail, Helix pomatia (Pulmonata: Helicidae)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 123 (1): 218–234. doi:10.1093/biolinnean/blx135. ISSN 0024-4066.

- ^ Korábek, Ondřej; Juřičková, Lucie; Petrusek, Adam (2021-12-31). "Diversity of Land Snail Tribe Helicini (Gastropoda: Stylommatophora: Helicidae): Where Do We Stand after 20 Years of Sequencing Mitochondrial Markers?". Diversity. 14 (1): 24. doi:10.3390/d14010024. ISSN 1424-2818.

- ^ a b "Roman Snail (Helix pomatia)". iNaturalist. Retrieved 2024-07-15.

- ^ Forsyth, Robert G.; Kamstra, James (2019-11-17). "Roman Snail, Helix pomatia (Mollusca: Helicidae), in Canada". The Canadian Field-Naturalist. 133 (2): 156. doi:10.22621/cfn.v133i2.2150. ISSN 0008-3550. S2CID 214283688.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Species summary for Helix pomatia". AnimalBase, last modified 5 March 2009, accessed 6 September 2010.

- ^ Heller J.: Life History Strategies. in Barker G. M. (ed.): The biology of terrestrial molluscs. CABI Publishing, Oxon, UK, 2001, ISBN 0-85199-318-4. 1–146, cited page: 428.

- ^ Tluste, Claudia; Birkhofer, Klaus (2023-04-14). "The Roman snail (Gastropoda: Helicidae) is not a generalist herbivore, but shows food preferences for Urtica dioica and plant litter". Journal of Natural History. 57 (13–16): 758–770. doi:10.1080/00222933.2023.2203335. ISSN 0022-2933.

- ^ Cuttelod, A.; Seddon, M.; Neubert, E. (30 April 2024). "European Red List of Non-marine Molluscs" (PDF). European Commission.

- ^ "RIS - Oö. Natur- und Landschaftsschutzgesetz 2001 - Landesrecht konsolidiert Oberösterreich, Fassung vom 22.07.2023". www.ris.bka.gv.at. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ "Besonders geschützte Pflanzen- und Tierarten des Burgenlandes gem. §§ 15a und 16 des Burgenländischen Naturschutz- und Landschaftspflegegesetzes, LGBl. Nr. 27/1991 in der Fassung LGBl. Nr. 20/2016" (PDF). 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981". 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "Arrêté du 24 avril 1979 fixant la liste des escargots dont le ramassage et la cession à titre gratuit ou onéreux peuvent être interdits ou autorisés - Légifrance". www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved 2023-07-22.

- ^ Miljøministeriet (2021-03-25), Bekendtgørelse om fredning af visse dyre- og plantearter og pleje af tilskadekommet vildt, retrieved 2023-07-22

- ^ Roy, Alexander B (1987). Methods in Enzymology, Volume 143, Sulfatases from Helix pomatia. Academic Press. pp. 361–366. ISBN 9780121820435.

- ^ Buono, Giuseppe Del (2015-02-24). "The roman snail". Wall Street International. Retrieved 2020-08-17.

- ^ "Snail Cultivation (Heliciculture)". The Living World of Molluscs. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

Further reading

- Egorov R. (2015). "Helix pomatia Linnaeus, 1758: the history of its introduction and recent distribution in European Russia". Malacologica Bohemoslovaca 14: 91–101. PDF

- (in Russian) Roumyantseva E. G. & Dedkov V. P. (2006). "Reproductive properties of the Roman snail Helix pomatia L. in the Kaliningrad Region, Russia". Ruthenica 15: 131–138. abstract Archived 2018-12-22 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Editio decima, reformata [10th revised edition], vol. 1: 824 pp. Laurentius Salvius: Holmiae

- Korábek, O., Juřičková, L. & Petrusek, A. (2015). Splitting the Roman snail Helix pomatia Linnaeus, 1758 (Stylommatophora: Helicidae) into two: redescription of the forgotten Helix thessalica Boettger, 1886. Journal of Molluscan Studies 82: 11–22

- Animal Diversity Web page