Sanaʽa manuscript

| Quran |

|---|

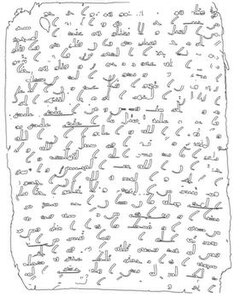

The Sanaa palimpsest (also Ṣanʽā’ 1 or DAM 01-27.1) or Sanaa Quran is one of the oldest Quranic manuscripts in existence.[1] Part of a sizable cache of Quranic and non-Quranic fragments discovered in Yemen during a 1972 restoration of the Great Mosque of Sanaa, the manuscript was identified as a palimpsest Quran in 1981 as it is written on parchment and comprises two layers of text.

- The upper text entirely conforms to the standard Uthmanic Quran in text and in the standard order of surahs (chapters).

- The lower text, which was erased and written over by the upper text, but can still be read with the help of ultraviolet light and computer processing, contains many variations from the standard text. The sequence of its chapters corresponds to no known Quranic order.

A partial reconstruction of the lower text was published in 2012,[2] and a reconstruction of the legible portions of both lower and upper texts of the 38 folios in the Sana'a House of Manuscripts was published in 2017 utilising post-processed digital images of the lower text.[3] A radiocarbon analysis has dated the parchment of one of the detached leaves sold at auction, and hence its lower text, to between 578 AD (44 BH) and 669 AD (49 AH) with a 95% accuracy.[4] The earliest leaves have been tested at three laboratories and dated to 388–535 AD. Other folios have similar early dates.

History

Discovery

In 1972, a construction workers renovating a wall in the attic of the Great Mosque of Sanaa in the Yemen Arab Republic came across large quantities of old manuscripts and parchments, many of which were deteriorated. Not realizing their significance, the workers gathered up the documents, packed them away into some twenty potato sacks, and left them on the staircase of one of the mosque's minarets.[5]

Isma'il al-Akwa' bin Ali, then the president of the Yemeni Antiquities Authority, realized the potential importance of the find. Al-Akwa' sought international assistance in examining and preserving the fragments, and in 1979 managed to interest a visiting German scholar, who in turn persuaded the West German government to organize and fund a restoration project.[5] The preserved fragments comprise Quranic and non-Quranic material.[6]

Restoration project

Restoration of the fragments began in 1980 under the supervision of the Yemeni Department for Antiquities. It was funded by the Cultural Section of the German Foreign Ministry.[2] The find includes 12,000 Quranic parchment fragments. All of them, except 1500–2000 fragments, were assigned to 926 distinct Quranic manuscripts as of 1997. None is complete and many contain only a few folios apiece.[2] Albrecht Noth (University of Hamburg) was the director of the project. Work on the ground began in 1981 and continued through the end of 1989, when the project terminated with the end of funding. Gerd R. Puin (University of Saarland) was the director beginning with 1981. His involvement came to an end in 1985, when Hans-Caspar Graf von Bothmer (University of Saarland) took over as the local director. Bothmer left Ṣan'ā' in the following year, but continued to run the project from Germany, traveling to the site almost every year.

Beginning in 1982, Ursula Dreibholz served as the conservator for this project, and worked full-time in Ṣan'ā' until the end of 1989. She completed the restoration of the manuscripts. She also designed the permanent storage, collated many parchment fragments to identify distinct Quranic manuscripts, and directed the Yemeni staff in the same task. The manuscripts are located in the House of Manuscripts, the Dār al-Makhṭūṭāt (DAM), in Ṣan'ā', Yemen. After 1989, Bothmer would visit the collection periodically. In the winter of 1996–97, he microfilmed all of the parchment fragments that have been assigned to distinct Quranic manuscripts. Of the remaining 1500–2000 fragments, he microfilmed a group of 280. The microfilms are available in Ṣan'ā' in the House of Manuscripts.[2] A selection of 651 images of fragments from the Sana'a cache - including several from DAM 01-27.1, has been issued on a CD-ROM through the UNESCO 'Memory of the World' programme.

The Sana'a Palimpsest was given the catalog number DAM 01-27.1, indicating a manuscript with variable lines to the page (hence '01'), written line length of approx. 27 cm (11"), and with a sequence indicator of '1'. By 2015 some 38 folio fragments had been identified as likely to belong to this particular manuscript. From 2007, a joint Italian-French team under Sergio Noja Noseda and Christian Robin undertook to produce new high-resolution digital images of DAM 01-27.1 (and other selected manuscripts in the cache), under both natural and ultra-violet light, which have since been subject to extensive computerised post-processing by Alba Fedeli to separate upper from lower texts. The high resolution images form the basis for the editions of both Sadeghi and Goudarzi, and of Asma Hilali.[7]

Contents of the manuscript

The manuscript is a palimpsest, meaning the parchment was written over once. The original text (the "lower" text) was erased, and written over a second time (the "upper" text) with this process potentially being repeated over time with the same parchment.[citation needed] In the Sana'a palimpsest, both the upper and the lower text are the Qur'an written in the Hijazi script. The upper text appears to present a complete text of the Qur'an, as did the lower text according to a codicological reconstruction by Éléonore Cellard (this had been a question of scholarly debate).[8] In the standard Qur'an, the chapters (surahs) are presented in an approximate sequence of decreasing length; hence a fragmentary Qur'an that follows the standard order of suras can generally be assumed to have once presented the complete text, but the contrary is not the case. Cellard's reconstruction has found that despite differences of sura sequence, the lower text too follows this same principle.[citation needed]

The manuscript that was discovered, however, is not complete. About 82 folios have been identified as possible sheets presenting the upper text, of which 38 are in Yemen's Dār al-Makhṭūṭāt (House of Manuscripts)[2] and 4 in private collections (after being auctioned abroad).[9] In addition in 2012, 40 palimpsest folios conserved in the Eastern Library of the Grand Mosque in Sana’a and published in 2004, were recognised as likely being detached folios of the upper text of DAM 01-27.1.[10] Many of the folios in the House of Manuscripts are physically incomplete and in only 28 is the upper writing legible (due to damage),[11] whereas those in private possession[9] or held by the Eastern Library are generally in a better condition.[10] These 82 folios comprise roughly half of the Quran. The parchment is of inferior quality, with many folios having holes around which both upper and lower text have been written. However, when the scale of the writing and the provision of marginal spaces is taken into account, the overall quantity of animal hides implied as being committed to the production of a full manuscript of the Qur'an would not have been less than for such high quality Qur'ans as the Codex Parisino-petropolitanus (BNF Arabe 328(ab)).

Historian Michael Cook sums up preliminary work on the Sana'a fragments as of 2000 thusly:

First, the range of variants is said to be considerably greater than is attested in our literary sources, though in character the variation does not appear to be very different from the kind of thing these sources record.

Second, the orthography of these – and other – early fragments diverges from that with which we are familiar in one rather striking respect, namely the frequent failure to mark the long ā as part of the consonantal skeleton in such words as qāla, 'he said' (the spelling ql which appears in these fragments would in our text be read as qul, meaning 'say!').

Last but not least, those fragments which show the end of one Sūra and the beginning of another reveal some clear deviations from the standard order of the Sūras; these deviations are comparable to those reported by the literary sources for a couple of the versions superseded by the ʿUthmānic codex, but they do not regularly coincide with them.[12]

Upper text

The upper text conforms entirely with that underlying the modern Quran in use, and has been dated as probably from sometime between the end of the 7th and the beginning of the 8th century CE.[13] Asma Hilali provides a full transcription of the upper text from the 26 legible folios in the House of Manuscripts, and found 17 non-orthographic variants in these pages, where readings differ from those in the "standard" Qur'an text, as presented in the 1924 Cairo edition. Five of these 17 variants in the upper text correspond to known Qira'at readings in the tradition of quranic variants.

The density of the writing of the upper text varies from page to page and within pages, such that the amount of text transcribed on each page varies from 18.5 lines of the standard Cairo edition to as many as 37 lines. Subsequent to the completion of the text, polychrome decoration has been added in the form of bands separating the suras, and indicators of 10, 50 and 100 verse divisions in a variety of particular forms. Much of these decorations are unfinished. In addition, the upper text formerly included individual verse separators – some contemporary with the text, others inserted later. The counts of verses corresponding to the polychrome verse indicators are not consistent with the counts of individual verse indicators, implying that the former were copied across other Qur'ans.

Lower text

The surviving lower text from 36 of the folio in the House of Manuscripts, together with the lower text from those auctioned abroad, were published in March 2012 in a long essay by Behnam Sadeghi (Professor of Islamic Studies at Stanford University) and Mohsen Goudarzi (PhD student at Harvard University).[2] Prior to that, in 2010, Sadeghi had published an extensive study of the four folios auctioned abroad, and analyzed their variants using textual critical methods.[9] The German scholar Elizabeth Puin (lecturer at Saarland University), whose husband was the local director of the restoration project until 1985, has also transcribed the lower text of several folios in five successive publications.[14][15][16][17] The lower text of the palimpsest folios in the Eastern Library has not been studied or published yet, and it is not known how many of these folios may witness the same lower text as those in the House of Manuscripts; however, it appears likely that the four auctioned folios (whose lower texts have been studied, and which do appear to witness the same lower text) came from this section of the manuscript, and not from DAM 01-27.1. While transcription from Hamdoun's photographs are a particularly difficult challenge, Hythem Sidky has identified lower textual sequences in most of the Eastern Library folios.[8]

The lower text was erased and written over, but due to the presence of metals in the ink, the lower text has resurfaced, and now appears in a light brown color, the visibility of which can be enhanced in ultra-violet light.[9] Parchment was expensive and durable, and so it was common practice to scrape the writing from disused and damaged texts for potential re-use. But while there are other known instances of disused Qur'ans being reused for other texts, there are only a few known instances of a new Qur'an being written using re-used parchment, and all these examples are believed to have been from the Sana'a cache. The re-use in this case may have been purely for economic reasons. The standardization of the Quranic text around 650 CE by 'Uthmān may have led to a non-standard lower text becoming obsolete, and erased in accordance with authoritative instructions to that effect.[18]

In places, individual readings in the lower text appear to have been corrected in a separate hand to conform better to corresponding readings in the standard Qur'an. Elizabeth Puin has termed this hand the 'lower modifier', and proposes that these corrections were undertaken before the whole lower text was erased or washed off.

Although the suras of the lower text do not follow the canonical order, nevertheless, with only two exceptions, within each sura, the surviving lower text presents the verses in the same order as the standard Qur'an – the exceptions being in sura 20, where Sadeghi and Goudarzi find that verses 31 and 32 are swapped, and in sura 9, where Sadeghi and Goudarzi find that the whole of verse 85 is absent, which he explains as "parablepsis, a form of scribal error in which the eye skips from one text to a similar text".[19] Neither of these passages of the lower text are in folios that Asma Hilali found to be legible. Some of the variants between the lower text and the standard Qur'an are provided by Sadeghi and Goudarzi below.[20] It is noticeable that the Lower text has many variations of words and phrases in comparison to the text of the standard Qur'an, however they rarely diverge from the fundamental meaning that the text is intending to communicate.

Stanford folio

| recto [21] | Visible Traces | Reconstruction | Standard Text |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quran 2 (al-Baqarah), verse 191 Line 4 |

ﺣ/ / ٮٯٮـ(ـلو) کم | حَتّی يُقـٰتِلوکُم | حَتَّىٰ يُقَـٰتِلُوكُمْ فِيهِ |

| Quran 2:191 Line 5 |

د لک جز ا ا لکڡر ٮں | ذَٰلِکَ جَزاءُ الکـٰفِرينَ | كـذَٰلِكَ جَزَآءُ ٱلْكَـٰفِرِينَ |

| Quran 2:192 Line 5 |

ا نتـ(ﻬ)ـﻮ | إنتَهَو | انتَهَوا |

| Quran 2:193 Line 6 |

حٮا | حَتّا | حَتّی |

| Quran 2:193 Line 7 |

و ٮکو ں ا لد ٮں کله ﻟ[ﻠ]ﻪ | و يَكُونَ الدِّينُ كُلُّهُ لِلَّـهِ | وَيَكُونَ ٱلدِّينُ لِلَّـهِ |

| Quran 2:194 Line 10 |

و من اعٮدی | وَ مَنِ اعتَدَی | فَــمَنِ ٱعْتَدَى |

| Quran 2:194 Line 11 |

ڡا ﻋٮـ/ / و | فاعتدو | فَٱعْتَدُوا |

| Quran 2:194 Line 11 |

ما اعٮد ی علٮكم ٮه | مَا اعتَدَی عَلَيكُم بِه | مَا ٱعْتَدَىٰ عَلَيْكُمْ |

| Quran 2:196 Line 17 |

ڡـﻤ// ٮٮسر مں ا لهد ی | فَما تَيَسَّر مِن الهَدی | فما استَيسَرَ مِنَ ٱلْهَدْىِ |

| Quran 2:196 Line 17 |

و لا تحلٯو ا | وَلَا تَحلِقُوا | وَلَا تَحْلِقُوا رُءُوسَكُمْ |

| Quran 2:196 Line 18 |

ڡا ﮞ كا ﮞ ا حد ﻣٮكم | فَإن كان أحَدٌ مِنكُم | فَمَن كَانَ مِنكُم |

| Quran 2:196 Line 19 |

ڡد ٮه | فِديَةٌ | فَـفِديَةٌ |

| Quran 2:196 Line 20 |

مں صٮم او نسک | مِن صِيٰمٍ أَو نُسُكٍ | مِن صِيَامٍ أَوْ صَدَقَةٍ أَوْ نُسُكٍ |

David 86/2003 folio

| recto | Visible Traces | Reconstruction | Standard Text |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quran 2:209 Line 5, p. 46 |

مں [ٮـ]ﻌﺪ (ما ﺣ)ﺎ کم ا ﻟ(ﻬد) [ی]؛ | مِّن بَعْدِ مَا جَآءَكُمُ ٱلْهُدَىٰ | مِّن بَعْدِ مَا جَآءَتْكُمُ ٱلْبَيِّنَـٰتُ |

| Quran 2:210 Line 6, p. 46 |

هل ٮـ//ـﻄﺮ (و ﮞ) ا لا ا ﮞ (ٮـ)ﺎ ٮـ(ـٮـ)ﮑﻢ ا ﻟﻠﻪ | هَلْ تَنظُرُونَ إِلَّا أَن يَأْتِيَكُمُ ٱللَّـهُ | هَلْ يَنظُرُونَ إِلَّا أَن يَأْتِيَهُمُ ٱللَّـهُ |

| Quran 2:211 Line 9, p. 46 |

ا لعڡٮ | ٱلْعِقٰبِ | ٱلْعِقَابِ |

| Quran 2:213 Line 12, p. 46 |

ڡﺎ // (ﺳ)ـﻞ ا لـلـه | فَــأَرسَلَ اللهُ | فَـــبَعَثَ ٱللَّـهُ |

| Quran 2:213 Line 13, p. 46 |

ﻟ(ـٮـحکمو ا ٮـ)ـٮں ا لٮا س | لِــيَحْكُمُوا بَيْنَ ٱلنَّاسِ | لِــيَحْكُمَ بَيْنَ ٱلنَّاسِ |

| Quran 2:213 Line 15, p. 46 |

ا ﻟٮـ(ـٮـٮـ)ـٮت | ٱلْبَيِّنَٮٰتُ | ٱلْبَيِّنَـٰتُ بَغْيًا بَيْنَهُمْ |

| Quran 2:214 Line 17, p. 46 |

ا (ﺣﺴ)ـٮٮم | أَ حَسِبْتُمْ | أَمْ حَسِبْتُمْ |

| Quran 2:214 Line 17, p. 46 |

ا ﻟ[ـﺪ ٮں] (ﻣ)ـﮟ [ٯٮـ]ـلکم | ٱلَّذِينَ مِن قَبْلِكُم | ٱلَّذِينَ خَلَوْا۟ مِن قَبْلِكُم |

| Quran 2:214 Line 18, p. 47 |

ا لٮسا | ٱلْبَٔسَاءُ | ٱلْبَأْسَاءُ |

| Quran 2:215 Line 20, p. 47 |

ٮـ(ـسا) لو ٮک | يَسْأَلُونَكَ | يَسْـَٔلُونَكَ |

| Quran 2:217 Line 25, p. 47 |

عں ا ﻟ(ﺴ)ﻬﺮ ا لحر (م) [و] ﻋ(ـں) ٯٮل ڡـ[ـٮـ]ﻪ | عَنِ ٱلشَّهْرِ ٱلْحَرٰمِ وَعَنْ قِتٰلٍ فِيهِ | عَنِ ٱلشَّهْرِ ٱلْحَرَامِ قِتَالٍ فِيهِ |

| Quran 2:217 Line 26, p. 47 |

؛/--/ [و] (ﺻ)[ﺪ] عں /------/؛ | وَصَدٌّ عَن سَبِيلِهِ[22] | وَصَدٌّ عَن سَبِيلِ ٱللَّـهِ وَكُفْرٌۢ بِهِ |

Folio 4

| recto / verso | Visible Traces | Reconstruction | Standard Text |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quran 11 (Hūd), verse 105 Folio 4, recto, l. 1, p. 51 |

ا (لا) مں ا {------}؛ | إلّا مَن أَذِنَ لَه | إِلَّا بِإِذْنِهِ |

| Quran 11:122 Folio 4, verso, l. 4, p. 52 |

ا / / (ﻣﻌ)[ﮑ]/ / {--------}؛ | إِنَّا مَعَكُم مُنتَظِرُونَ | إِنَّا مُنتَظِرُونَ |

| Quran 8 (al-Anfāl), verse 2 Folio 4, verso, l. 12, p. 52 |

ڡـ(ﺮ) ٯـٮ | ْفَرِقَت | ْوَجِلَت |

| Quran 8:.2 Folio 4, verso, l. 13, p. 52 |

ا ٮـ(ـٮٮـ)ﺎ | ءَايَـٰتُنا | ءَايَـٰتُهُ |

Folio 22

| recto / verso | Visible Traces | Reconstruction | Standard Text |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quran 9 (al-Tawbah), Verse 122 Folio 22, recto, l. 3, p. 62 |

ما [كـ]ﺎ ﮞ | مَا كَانَ | وَمَا كَانَ |

| Quran 9:122 Folio 22, recto, l. 4, p. 62 |

مں كل ا ﻣﻪ | مِن كُلِّ أُمَّةٍ | مِن كُلِّ فِرْقَةٍ |

| Quran 9:124 Folio 22, recto, l. 9, p. 62 |

و ا د ا ا ٮر لٮ | وَإِذَا أُنزِلَتْ | وَإِذَا مَا أُنزِلَتْ |

| Quran 9:125 Folio 22, recto, l. 12, p. 62 |

ڡی ٯلو ٮهم ر حس | فِى قُلُوبِهِم رِجْسٌ | فِى قُلُوبِهِم مَرَضٌ |

| Quran 9:125 Folio 22, recto, l. 13, p. 62 |

ر حر ا ا لی ر ﺣﺴ[ﻬ]ـﻢ | رِجزاً إِلَىٰ رِجْسِهِمْ | رِجساً إِلَىٰ رِجْسِهِمْ |

| Quran 9:125 Folio 22, recto, l. 13, p. 62 |

و ما ٮو ا و هم ڡـ(ـﺴٯـ)[ـﻮ] ﮞ | وَمَاتُوا۟ وَهُمْ فَـٰسِقُونَ | وَمَاتُوا۟ وَهُمْ كَـٰفِرُونَ |

| Quran 9:126 Folio 22, recto, l. 13, p. 62 |

ا [و] / / ٮر و | أَوَلَا يَرَوْ | أَوَلَا يَرَوْنَ |

| Quran 9:126 Folio 22, recto, l. 15, p. 62 |

و لا ٮـ(ـٮـ)ـﺪ كر و ﮞ | وَلَا يَتَذَكَّرُونَ | وَلَا هُمْ يَذَّكَّرُونَ |

| Quran 9:127 Folio 22, recto, l. 15, p. 62 |

و ا د ا ا [ٮـ]ـﺮ (ﻟ)ـٮ | وَإِذَا أُنزِلَتْ | وَإِذَا مَا أُنزِلَتْ |

| Quran 9:127 Folio 22, recto, l. 16, p. 62 |

هل ٮر ٮٮا | هَلْ يَرَىٰنَا | هَلْ يَرَىٰكُم |

| Quran 9:127 Folio 22, recto, l. 17, p. 62 |

ڡا ٮـ[ـﺼ](ـﺮ) ڡـ(ـﻮ) ا | فَـﭑنصَرَفُوا | ثُمَّ انصَرَفُوا |

| Quran 9:127 Folio 22, recto, l. 17, p. 62 |

ڡصر ڡ ا ﻟـﻠـﻪ | فَــصَرَفَ اللهُ | صَرَفَ ٱللَّـهُ |

| Quran 9:127 Folio 22, recto, l. 17, p. 62 |

د لک ٮـ(ﺎ ٮـ)//[ـﻢ] (ٯـ)ـﻮ م لا ٮڡٯهو ﮞ | ذَٰلِكَ بِأَنَّهُمْ قَوْمٌ لَّا يَفْقَهُونَ | بِأَنَّهُمْ قَوْمٌ لَّا يَفْقَهُونَ |

| Quran 9:128 Folio 22, recto, l. 18, p. 62 |

و لٯد حا کم | وَلَقَدْ جَاءَكُمْ | لَقَدْ جَاءَكُمْ |

| Quran 9:128 Folio 22, recto, l. 18, p. 62 |

ر سو ل ﻣٮـ(ﮑ)ـﻢ | رَسولٌ مِنْكُمْ | رَسُولٌ مِنْ أَنْفُسِکُمْ |

| Quran 9:128 Folio 22, recto, l. 19, p. 63 |

عر ٮر (ﻋ)ﻠ[ـٮـ](ﻪ) ما عٮٮکم | عَزِيزٌ عَلَيْهِ مَا عَنَّتَكُمْ | عَزِيزٌ عَلَيْهِ مَا عَنِتُّمْ |

| Quran 9:129 Folio 22, recto, l. 20, p. 63 |

ڡا / / (ٮـ)ـﻮ لو ا [ﻋ](ـٮـ)ـﮏ | فَإن تَوَلَّوْا عَنْكَ | فَإن تَوَلَّوْا |

| Quran 9:129 Folio 22, recto, l. 21, p. 63 |

ا لد ی لا ا ﻟ[ﻪ] ا لا ﻫﻮ | الَّذي لَا إِلَـٰهَ إِلَّا هُوَ | لَا إِلَـٰهَ إِلَّا هُوَ |

| Quran 19 (Maryam), verse 2 Folio 22, recto, l. 24, p. 63 |

ر ﺣ[ـﻤ]ﻪ | رَحْمَةِ | رَحْمَتِ |

| Quran 19:3 Folio 22, recto, l. 25, p. 63 |

ا د ٮا د ی ر ٮک ر ﻛ[ـر] ٮا | إِذْ نَادَىٰ رَبَّــكَ زَكَرِيَّا | إِذْ نَادَىٰ رَبَّــهُ |

| Quran 19:4 Folio 22, recto, l. 25, p. 63 |

و ٯل ر ٮی | وَقٰلَ رَبِّــي | قالَ رَبِّ |

| Quran 19:4 Folio 22, recto, l. 26, p. 63 |

و ٯل ر ٮی ا سٮعل ا لر ا س سٮٮا | وَقٰلَ رَبِّي ٱشْتَعَلَ ٱلرَّأْسُ شَيْباً | قَالَ رَبِّ إِنِّي وَهَنَ ٱلْعَظْمُ مِنِّي وَٱشْتَعَلَ ٱلرَّأْسُ شَيْبًا |

| Quran 19:4 Folio 22, recto, l. 26, p. 63 |

و لم ا کں ر ٮ ٮـ(ـد) عا ک | وَلَمْ أَکُنْ رَبِّ بِدُعَاءِكَ | وَلَمْ أَكُن بِدُعَائِكَ رَبِّ |

| Quran 19:5 Folio 22, recto, l. 27, p. 63 |

و ﺣ(ڡـ)ـٮ ا لمو ل مں و [ر] ا ی | وَ خِفْتُ ٱلْمَوَٰل مِن وَرٰاءِى | وَإِنِّى خِفْتُ ٱلْمَوَٰلِىَ مِن وَرٰاءِى |

| Quran 19:7 Folio 22, verso, l. 2-3, p. 63 |

؛{-----------------} (ٯد) و هٮٮا لک علما ر کٮا و ٮسر ٮه {----------------}(ﻪ) مں ٯـٮـ(ـﻞ) ﺳ//ـﻤٮـﺎ | ؛{يَـٰزَكَرِيَّا إِنَّا} قَد وَهَبْنَا لَكَ غُلٰماً زَكِيَّاً وَبَشَّرْنٰهُ {بِيَحْيیٰ لَمْ نَجْعَل ﻟَّ}ﻪُ مِن قَبْلُ سَمِيًّا[23] | يَـٰزَكَرِيَّا إِنَّا نُبَشِّرُكَ بِغُلَـٰمٍ ٱسْمُهُ يَحْيَىٰ لَمْ نَجْعَل لَّهُ مِن قَبْلُ سَمِيًّا |

| Quran 19:8 Folio 22, verso, l. 3-4, p. 63 |

ا //ﻰ ٮـ(ﮑ)ـﻮ ﮞ لی (ﻋ)ـلم {---------------} ﻟ[ﮑ]ـٮر عٮٮا | أَنَّىٰ يَكُونُ لِى غُلَـٰمٌ {وَقَدْ بَلَغْتُ مِنَ ٱ} لْكِبَرِ عِتِيًّا | أَنَّىٰ يَكُونُ لِى غُلَـٰمٌ وَكَانَتِ ٱمْرَأَتِى عَاقِرًا وَقَدْ بَلَغْتُ مِنَ ٱلْكِبَرِ عِتِيًّا |

| Quran 19:9 Folio 22, verso, l. 5, p. 63 |

و لم ٮک سا ی | وَلَمْ تَكُ شَاي | وَلَمْ تَكُ شَيْئًا |

| Quran 19:11 Folio 22, verso, l. 7, p. 64 |

؛{-}ـم حرح | ؛{ثُـ}ـمَّ خَرَجَ | فَــخَرَجَ |

| Quran 19:11 Folio 22, verso, l. 7, p. 64 |

ا (و) ﺣ(ﻰ) ا ﻟ(ـٮـ)ﻬﻢ | أَوْحَىٰ إِلَيْهِمْ | فَــأَوْحَىٰ إِلَيْهِمْ |

| Quran 19:12 Folio 22, verso, l. 8, p. 64 |

و علمٮه ا ﻟ(ـﺤ)ﮑﻢ | وَعَلَّمْنٰهُ الْحُكْمَ | وَآتَيْنَاهُ الْحُكْمَ صَبِيًّا |

| Quran 19:13 Folio 22, verso, l. 9, p. 64 |

حننا | حَنٰناً | وَحَنَاناً |

| Quran 19:14 Folio 22, verso, l. 10, p. 64 |

و لم ٮک | وَلَمْ يَكُ | وَلَمْ يَكُنْ |

| Quran 19:15 Folio 22, verso, l. 10, p. 64 |

و علٮه ا لسلم | وَعَلَيْهِ السَّلٰمُ | وَسَلَـٰمٌ عَلَيْهِ |

| Quran 19:19 Folio 22, verso, l. 15, p. 64 |

لنهب | لِنَهَبَ | لِأَهَبَ |

| Quran 19:21 Folio 22, verso, l. 17, p. 64 |

و هو ﻋﻠ//(ﻪ) ﻫ(ـٮـ)ـﮟ | وَهُوَ عَلَيْهِ هَيِّنٌ | هُوَ عَلَىَّ هَيِّنٌ |

| Quran 19:21 Folio 22, verso, l. 18, p. 64 |

و [ا] مر ا مٯصٮا | وَأَمْرًا مَّقْضِيًّا | وَكَانَ أَمْرًا مَّقْضِيًّا |

| Quran 19:22 Folio 22, verso, l. 18, p. 64 |

ڡحملٮ | فَحَمَلَتْ | فَحَمَلَتْــهُ |

| Quran 19:23 Folio 22, verso, l. 19, p. 64 |

ڡـﻠﻤ// ا حا ها ا لمحص | فَــلَمَّا أَجَاءَهَا ٱلْمَخٰضُ | فَأَجَاءَهَا ٱلْمَخَاضُ |

| Quran 19:23 Folio 22, verso, l. 20, p. 65 |

ٯٮل هد ا ا ﻟ(ـٮـ)[ـو] م | قَبْلَ هَـٰذَا الْيَوْمِ | قَبْلَ هَـٰذَا |

| Quran 19:24 Folio 22, verso, l. 20-21, p. 65 |

ڡٮـ[ـد] ٮها مں ٮـﺤٮـﻬ/----------/ ا لا ٮحر ٮی | فَنٰدٮٰهَا مِن تَحْتِهَـ/ـا مَلَكٌ/ أَلَّا تَحْزَنِى [24] | فَنَادَىٰهَا مِن تَحْتِهَا أَلَّا تَحْزَنِى |

| Quran 19:26 Folio 22, verso, l. 23, p. 65 |

و ٯـ// [ی] ﻋ(ـٮٮـ)ﺎ | وَقَرِّى عَيْنًا | وَقَرِّى عَيْنًا |

| Quran 19:26 Folio 22, verso, l. 24, p. 65 |

ﺻ[ـﻮ] (ما) [و ﺻﻤ]ـٮا | صَوْماً وَصُمْتاً | صَوْماً |

| Quran 19:26 Folio 22, verso, l. 24, p. 65 |

ﻟﮟ ا کلم | لَنْ أُکَلِّمَ | فَــلَنْ أُكَلِّمَ |

| Quran 19:27 Folio 22, verso, l. 25, p. 65 |

؛//ﺎ [ٮـ](ـت ٯو) [ﻣﻬ] ﺎ | فَأَتَتْ قَوْمَهَا | فَأَتَتْ بِهِ قَوْمَهَا |

| Quran 19:27 Folio 22, verso, l. 25, p. 65 |

لٯد ا ﺗٮت | لَقَدْ أَتَيْتِ | لَقَدْ جِئْتِ |

| Quran 19:28 Folio 22, verso, l. 26, p. 65 |

ما کا (ﮞ) ا ٮو [ک] (ا ٮا) //[ﻮ] ا | مَا كَانَ أَبُوكِ أَباً سُوءاً | مَا كَانَ أَبُوكِ ٱمْرَأَ سَوْءٍ |

Folio 31

| recto / verso | Visible Traces | Reconstruction | Standard Text |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quran 12 (Yūsuf), verse 19 Folio 31, recto, l. 4-5, p. 71 |

ْو {------} (ﻋﻠٮـ)// ٮـﻌ[ﺺ] (ا) ﻟ[ﺴ]/ /؛ | و {جَاءَت} عَلَيْهِ بَعْضُ السَّيَّارَةِ | وَجَاءَتْ سَيَّارَةٌ |

| Quran 12:19 Folio 31, recto, l. 6, p. 71 |

و ٯل | وَقٰلَ | قَالَ |

| Quran 12:19 Folio 31, recto, l. 7, p. 71 |

و (ا) ﻟ[ﻠﻪ] ﻋﻠ//ـﻢ ٮـﻤ(ﺎ) ٮڡعلو{}ﮞ | وَٱللَّـهُ عَلِيمٌ بِمَا يَفْعَلُونَ | وَٱللَّـهُ عَلِيمٌ بِمَا يَعْمَلُونَ |

| Quran 12:28 Folio 31, verso, l. 4, p. 72 |

ٯل ا //[ﻪ] (ﻛ)[ـٮد] ﻛﮟ | قٰلَ إِنَّهُ كَيْدَكُنَّ | قَالَ إِنَّهُ مِن كَيْدِكُنَّ |

| Quran 12:30 Folio 31, verso, l. 5, p. 72 |

ٮسو (ه) مں ا (هل) ا لمد [ٮـ]ـٮه | نِسْوَةٌ مِن أَهْلِ ٱلْمَدِينَةِ | نِسْوَةٌ فِي ٱلْمَدِينَةِ |

| Quran 12:30 Folio 31, verso, l. 5-6, p. 72 |

؛{---------------}/ / ٯـ(ـﺪ ﺳ)ﻌ(ڡـ)[ﻬﺎ] (ﺣ)[ـٮ] ڡٮـ//(ﻬ)ﺎ | ؛{ٱمْرَأَتُ ٱلْعَزِيزِ} قَدْ شَغَفَهَا حُبُّ فَتَٮٰهَا[25] | ٱمْرَأَتُ ٱلْعَزِيزِ تُرَٰوِدُ فَتَٮٰهَا عَن نَّفْسِهِ قَدْ شَغَفَهَا حُبًّا |

| Quran 12:31 Folio 31, verso, l. 7, p. 72 |

ڡلما ﺳﻤ[ﻌ]/ / مکر[ﻫ]ـﮟ | فَلَمَّا سَمِعَتْ مَكْرَهُنَّ | فَلَمَّا سَمِعَتْ بِــمَكْرِهِنَّ |

| Quran 12:31 Folio 31, verso, l. 8, p. 72 |

و{ } ﺣ(ﻌ)ﻠ/ / ﻟ(ﻬ)/ / (ﻣٮـﮑ)//؛ | وَجَعَلَتْ لَهُنَّ مُتَّكَـًٔا | وَأَعْتَدَتْ لَهُنَّ مُتَّكَـًٔا |

| Quran 37 (al-Ṣāffāt), verse 15 Folio 28, recto, l. 1, p. 102 |

و ٯلو ا هد ا {------}//ٮٮں | وَقٰلوا هذا سِحرٌ مُبينٌ | وَقالوا إن هـٰذا إِلّا سِحرٌ مُبينٌ |

Folio 28

| recto / verso | Visible Traces | Reconstruction | Standard Text |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quran 37:19 Folio 28, recto, l. 4, p. 102 |

/ /ڡا دا ﻫ[ـﻢ] ﻣﺤ(ـﺼ)ـﺮ | فَإذا هُم مُحضَرون | فَإِذا هُم يَنظُرونَ |

| Quran 37:22 Folio 28, recto, l. 6, p. 102 |

ا ٮـ(ﻌٮـ)ﻮ ا | إبعَثوا | احشُرُوا |

| Quran 37:22 Folio 28, recto, l. 6, p. 102 |

ﻃـ//[ـﻤ]ـﻮ ا { } | الَّذينَ ظَلَموا | الَّذينَ ظَلَموا وَأَزوٰجَهُم |

| Quran 37:23 Folio 28, recto, l. 8, p. 102 |

صر ٮط ا (ﻟﺤ)ﺤٮم | صِر ٮطِ الجَحيم | صِرٰطِ الجَحيمِ |

| Quran 37:25 Folio 28, recto, l. 9, p. 103 |

/ / لا ٮٮٮصرو | لا تَنٮٰصَرون or لا تَتَنٰصَرون | لا تَناصَرون |

| Quran 37:27 Folio 28, recto, l. 10, p. 103 |

ڡـ(ﺎ ٯـ)ـٮل | فَـﺄ قبَلَ | وَأَقبَلَ |

| Quran 37:48 Folio 28, verso, l. 3, p. 103 |

ﻋ(ـٮـ)[ـد] هم | عِندَهُم | وَعِندَهُم |

| Quran 37:50 Folio 28, verso, l. 4, p. 103 |

علا | عَلا | عَلی |

| Quran 37:54 Folio 28, verso, l. 7, p. 103 |

ٯهل | فَــﻬَﻞ | هَل |

| Quran 37:56 Folio 28, verso, l. 8, p. 103 |

ﻟ(ـٮـﻌ)ـو ٮں | لَتُغوِينِ | ِلَتُرْدِين |

| Quran 37:58 Folio 28, verso, l. 9, p. 103 |

و ما ٮحں | وَما نَحنُ | أَفَما نَحْنُ |

The page numbers refer to the edition by Sadeghi and Goudarzi.[2] In their edition, a reliably read but partially visible letter is put in parentheses, while a less reliably read letter is put inside brackets. A pair of forwarding slashes mark an illegible area on the folio, while braces indicate a missing part of the folio. The list here does not include all the spelling variants. (Note: In the above table, parentheses or brackets are left out if they appear at the very beginning or end of a phrase, to avoid text alignment issues. Braces or forward slashes are preserved in all instances, but with the insertion of extra semicolons that help preserve text alignment.)

Characteristics of the hand in the lower text

Lines per page of the lower text vary from 25 to 30, and sometimes stray markedly from the horizontal. There are occasional diacritical dots to differentiate consonants, but only one possible instance of a dotted short vowel indicator. Otherwise, the text is written for the most part in scriptio defectiva without indication of long vowels, except that particular words are written in scriptio plena, for which the letter alif indicates a long vowel. Both verse indicators and crudely decorated sura divisions are provided in the original hand, and there are indicators for divisions of 100 and 200 verses. Individual verse divisions are indicated by patterns of dots, although the form of these patterns varies in different folios of the manuscript. Given that many verse divisions have been lost entirely, and that residual letter elements from deleted words may present as similar patterns of dots, it is not possible to determine how far the verse divisions in the lower text correspond to any of the many known traditions of quranic verse division. However, it does appear that the basmala formula is sometimes counted as a separate verse, contrary to the later quranic standard.

Reading instruction

Visible in the lower text is the beginning of sura 9, which follows on from sura 8 in this text. Sura 9 At-Tawba is the only sura in the standard Qur'an which is not introduced by the basmala formula "In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful", the absence of the formula at this place sometimes being stated as indicating that the two suras 8 and 9 are to be considered as a single section of the Qur'an. Nevertheless, the lower text in the Sana'a palimpsest does introduce sura 9 with the basmala formula (on line 8 of folio 5a), but the following line then begins la taqul bi-smi Allahi ('Do not say "in the name of God"'). This notice therefore represents the intrusion of a non-canonical reading instruction into the body of the canonical text, undifferentiated from that text, and in this respect no parallel is known in the tradition of written Qur'ans. Moreover, by setting out the basmala formula, and then countermanding its being recited out loud, the text as it stands would create an uncertainty in ritual use to a degree that the conventions of quranic writing are generally designed to prevent.

Hilali's exercise book thesis

Asma Hilali has argued that this reading instruction indicates a possible correction or notice by some kind of a senior teacher or scribe, supporting her hypothesis of a scribal "exercise" in the context of "school exercises" [26] In her analysis she has argued that both the upper and lower text show characteristics of being schoolroom "exercises" in quranic writing, in which case she also argues the scraping and re-use of the palimpsest is to be expected.

Hilali reported various types of erasures that could be due to the palimpsesting technique.[8] François Déroche contends only scraping could have removed the lower ink, and Sadeghi finds some evidence of such scraping. Elisabeth Puin contends that the primary codex was scraped off and re-written, in some cases, and in other cases the entire codex was erased by soaking the sheets and stretching them.[8]

However, Nicolai Sinai has criticised Hilali's thesis in detail in a review of her work[27] and Éléonore Cellard's work on a much larger number of folios than Hilali examined is also considered highly relevant.[8] Quranic manuscript scholar Hythem Sidky has cited the paper by Sinai for "criticism of her reading of the lower text and overall thesis" and Cellard's paper "for a codicological reconstruction of portions of the undertext demonstrating the document's status as a codex and the product of professional scribes".[28]

Issues in current scholarship

Dating of the lower text

The lower text is believed to have been written sometime between 632–669 CE, as the parchment of the Stanford folio has been radiocarbon dated with 95% accuracy to before 669 CE, and 75% probability from before 646 CE. François Déroche puts the lower text to the second half of the 7th century.[29] The lower text includes sura At-Tawba, which is believed in Islamic tradition to have been recited by Muhammad in 632 CE.[1]

Relation of the lower text to other non-'Uthmanic quranic traditions

The lower text of the Sana'a manuscript is capable of being distinguished from the upper text only in some folios, and several folios are so damaged as to be wholly unreadable, so Asma Hilali was able to transcribe the lower text contents of only 11 folios, in which she identified 61 non-orthographic variations from the 1924 Cairo edition. The variations observed in the lower text tend to be more substantial than those observed in the upper text, for the most part involving the addition of whole words and phrases. Islamic tradition has described that other than the standard 'Uthmanic Qur'an, there existed two independently preserved and copied Qur'anic codices from two Companions of the Prophet, those of Abdullah ibn Masud and Ubayy ibn Ka'b.[30]

Before the Sana'a manuscript, no partial or complete Qur'anic codex in a tradition other than the 'Uthmanic standard had ever been found. And while early Islamic witnesses report readings found in these two alternative codices, they do not collate their full texts. Elizabeth Puin and Asma Hillali report little or no correspondence between the variations from the 'Uthmanic Qur'an that they have found in the lower text with those reported for Abdullah ibn Masud or Ubayy ibn Ka'b, whereas Sadeghi and Goudarzi claim to be able to identify extra variations in the lower text of the Sana'a codex with similarities to the codex of Ibn Masud as well as differences. Hence they report an overlap between the variants of Ibn Masud and the Sana'a manuscript, although there are variants in Ibn Masud not found in the lower text and vice versa, with the differences much outnumbering the correspondences.[31] Additionally, the Sana'a manuscript puts sura Tawba after sura Anfal, whereas Ibn Masud's codex did the opposite. [32] Nevertheless, with the aid of a much more comprehensive identification of lower textual sequences in the available folios, including those of the Eastern Library, Cellard has identified numerous similarities with the sura sequences reported for both Ibn Masud and Ubayy.[8]

Media coverage

Puin and his colleague Graf von Bothmer have published only short essays on the Ṣana'a find. In a 1999 interview with Toby Lester, the executive editor of The Atlantic Monthly website, Puin described the preserved fragments by the following:

So many Muslims have this belief that everything between the two covers of the Quran is Allah's unaltered word. They like to quote the textual work that shows that the Bible has a history and did not fall straight out of the sky, but until now the Quran has been out of this discussion. The only way to break through this wall is to prove that the Quran has a history too. The Sana'a fragments will help us accomplish this.[5]

Puin claimed that the Yemeni authorities want to keep work on the Ṣana'a manuscripts "low-profile".[5]

In 2000, The Guardian interviewed a number of academics for their responses to Puin's remarks, including Tarif Khalidi, and Professor Allen Jones, a lecturer in Koranic Studies at Oxford University. In regard to Puin's claim that certain words and pronunciations in the Koran were not standardized until the ninth century, The Guardian reported:

Jones admits there have been 'trifling' changes made to the Uthmanic recension. Khalidi says the traditional Muslim account of the Koran's development is still more or less true. 'I haven't yet seen anything to radically alter my view,' he says. [Jones] believes that the San'a Koran could just be a bad copy that was being used by people to whom the Uthmanic text had not reached yet. 'It's not inconceivable that after the promulgation of the Uthmanic text, it took a long time to filter down.'[33]

The article noted some positive Muslim reaction to Puin's research. Salim Abdullah, director of the German Islamic Archives, affiliated to the Muslim World League, commented when he was warned of the controversy Puin's work might generate, "I am longing for this kind of discussion on this topic."[33]

Based on interviews with several scholars, Sadeghi and Goudarzi question Puin's claims regarding Yemeni suppression of research on the manuscripts and Puin's statement that the Yemenis did not want others to know that work was being done on them. For instance, they note that in 2007 Sergio Noja Noseda (an Italian scholar) and Christian Robin (a French archaeologist) were allowed to take pictures of the Sana'a palimpsest. They write that according to Robin, his colleagues were "granted greater access than would have been possible in some European libraries."[34] They report a similar view from Ursula Dreibholz, the conservator for the restoration project, who describes the Yemenis as supportive.[34] They quote Dreibholz as saying that the Yemenis "brought school children, university students, foreign delegations, religious dignitaries, and heads of state, like François Mitterrand, Gerhard Schröder, and Prince Claus of the Netherlands, to see the collection."[34]

Sadeghi and Goudarzi conclude:

Although the Yemeni authorities' openness proved a boon to scholarship, they were to be punished for it. The American media amplified the erroneous words of G. Puin, purveying a narrative that belittled Yemen and misrepresented the work done there. The Arab press, in turn, exaggerated the American story. The outcome was a media discourse in Yemen borne of three stages of misrepresentation. This embarrassed the Yemeni authorities responsible for the House of Manuscripts, and the Head of the Antiquities Department had to defend before Parliament the decision to bring in the foreigners.[34]

The Sana'a palimpsest/lower text is one of several of the earliest Quranic manuscripts to be highlighted in the media in recent years.

- Its date (estimated to be between 578 CE and 669 CE with a 95% accuracy);[4] compares with

- the Birmingham Quran manuscript (radiocarbon dated slightly earlier – to between 568 and 645 CE with a 95.4% accuracy),[35][36] which became a news story in 2015;

- a Quran manuscript examined by the University of Tübingen in 2014 is estimated to be more recent, dated from the early second half of the 7th century[37] (649–675);[38]

- the Codex Parisino-petropolitanus, also dated to the early second half of the 7th century,[39] containing 46% of the text of the Quran, studied by François Déroche that made news in 2009.[40]

In the wake of the Birmingham Quran manuscript news story of 2015, Gabriel Said Reynolds, professor of Islamic Studies and Theology, published a commentary on the differences between extant ancient Qur'an copies, speculating that the lower script of the Sana'a palimpsest, which not only "does not agree with the standard text read around the world today", but whose variants "do not match the variants reported in medieval literature for those codices kept by companions" of Muhammad, and "has so many variants that one might imagine it is a vestige of an ancient version that somehow survived Uthman's burning of all versions of the Qur’an except his own". Radiocarbon dating notwithstanding, Reynolds asserts that the "Sanaa manuscript... is almost certainly the most ancient Qur’an manuscript."[41]

See also

- Early Quranic manuscripts

- Codex Parisino-petropolitanus

- Topkapi manuscript

- Samarkand Kufic Quran

- Birmingham Quran manuscript

- History of the Quran

- Historiography of early Islam

- Textual criticism

- Gerd R. Puin

References

- ^ a b Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012.

- ^ Hilali 2017.

- ^ a b Sadeghi & Bergmann 2010, p. 348.

- ^ a b c d Lester 1999.

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 9.

- ^ Hilali 2017, p. xv.

- ^ a b c d e f Cellard, Éléonore (2021). "The Ṣanʿāʾ Palimpsest: Materializing the Codices". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 80 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1086/713473. S2CID 233228467.

- ^ a b c d Sadeghi & Bergmann 2010.

- ^ a b Hamdoun 2004.

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 37.

- ^ Cook, The Koran, 2000: p.120

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 7.

- ^ Puin 2008.

- ^ Puin 2009.

- ^ Puin 2010.

- ^ Puin 2011.

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 27.

- ^ Ṣan'ā' 1 and the Origins of the Qur'ān, Behnam Sadeghi & Mohsen Goudarzi. Walter de Gruyter. 2012.

Another exception concerns verse 85 of sūra 9, which is missing. At sixteen words, this omission is found to be an outlier when compared to the sizes of other missing elements in C-1, which are much shorter. The anomaly may be explained by the common phenomenon of parablepsis, a form of scribal error in which the eye skips from one text to a similar text, in this case, from the instance of ūna followed by a verse separator and the morpheme wa at the end of verse 84 to the instance of ūna followed by a verse separator and the morpheme wa at the end of verse 85.

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, pp. 41–129.

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 44. The hypothetical interpolation of texts for the missing parts in this and the next row are based on Sadeghi & Goudarzi's fn. 216 and 218.

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 47. According to Sadeghi & Goudarzi's fn. 118, "The traces [after ʿan] match sabīlihi." According to next footnote, "The phrase wa-kufrun bihi is not present immediately [after sabīlihi]. Either it is missing or it (or a smaller phrase such as wa-kufrun) is written at the beginning of the line, before wa-ṣaddun."

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 63. The hypothetical interpolation of texts for the missing parts in this and the next row are based on Sadeghi & Goudarzi's fn. 216 and 218.

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 65. The hypothetical interpolation of text for the illegible part is based on Sadeghi & Goudarzi's fn. 229.

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 72. The reconstructed text here is based on suggestions in Sadeghi & Goudarzi's fn. 279 and 281.

- ^ Hollenberg, David; Rauch, Christoph; Schmidtke, Sabine (2015-05-20). The Yemeni Manuscript Tradition. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-28976-5.

- ^ Sinai, Nicolai (2020). "Beyond the Cairo Edition: On the Study of Early Qurʾānic Codices". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 140 (2020): 189–204. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.140.1.0189. S2CID 219093175.

- ^ Sidky, H. (2020) "On the Regionality of Qurʾānic Codices", Journal of the International Qur’anic Studies Association, 5(1) doi:10.5913/jiqsa.5.2020.a005

- ^ Déroche, François (2013-12-02). Qurans of the Umayyads. BRILL. p. 54. ISBN 9789004261853.

I would therefore suggest, on the basis of the various points I enumerated, that the Codex San'a I was written during the second half of the 1st/7th century and erased at the earliest by the middle of the following century.

- ^ Nöldeke, Theodor; Schwally, Friedrich; Bergsträsser, Gotthelf; Pretzl, Otto (2013). "The Genesis of the Authorized Redaction of the Koran under the Caliph ʿUthmān". In Behn, Wolfgang H. (ed.). The History of the Qurʾān. Texts and Studies on the Qurʾān. Vol. 8. Translated by Behn, Wolfgang H. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 251–275. doi:10.1163/9789004228795_017. ISBN 978-90-04-21234-3. ISSN 1567-2808. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 19-20.

- ^ Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 26.

- ^ a b Taher 2000.

- ^ a b c d Sadeghi & Goudarzi 2012, p. 36.

- ^ "Birmingham Qur'an manuscript dated among the oldest in the world". University of Birmingham. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ "'Oldest' Koran fragments found in Birmingham University". BBC. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ "Rarität entdeckt: Koranhandschrift stammt aus der Frühzeit des Islam".

- ^ Dan Bilefsky for The New York Times (22 July 2015). "A Find in Britain: Quran Fragments Perhaps as Old as Islam". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Deroche, Francois (2009). La Transmission Écrite Du Coran Dans Les Débuts De L'Islam: Le Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus. p. 177.

- ^ Deroche, Francois. La Transmission Écrite Du Coran Dans Les Débuts De L'Islam: Le Codex Parisino-Petropolitanus. p. 172.

- ^ Reynolds, Gabriel Said (7 Aug 2015). "Variant readings; The Birmingham Qur'an in the context of debate on Islamic origins". academia.edu. Gabriel Said Reynolds. Retrieved 14 Feb 2018.

Among the manuscripts... discovered in 1972... of the Great Mosque of Sanaa in Yemen was a rare Qur'anic palimpsest – that is, a manuscript preserving an original Qur'an text that had been erased and written over with a new Qur'an text. This palimpsest has been analysed by... Gerd and Elisabeth Puin, by Asma Hilali of the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London, and later by Behnam Sadeghi of Stanford University... What all of these scholars have discovered is remarkable: the earlier text of the Qur'an contains numerous variants to the standard consonantal text of the Qur'an.

Sources

- Cook, Michael (2000). The Koran; A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285344-8. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Hilali, Asma (2017). The Sanaa Palimpsest: The Transmission of the Qur'an in the First Centuries AH. Qur'anic Studies Series. Oxford: Oxford University Press/Institute of Ismaili Studies. ISBN 978-0-19-879379-3. S2CID 193902896.

- Hilali, Asma (2015). "Was the Ṣanʿāʾ Qurʾān Palimpsest a Work in Progress?". In Hollenberg, David; Rauch, Christoph; Schmidtke, Sabine (eds.). The Yemeni Manuscript Tradition. Islamic Manuscripts and Books. Vol. 7. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. 12–27. doi:10.1163/9789004289765_003. ISBN 978-90-04-28825-6. ISSN 1877-9964. LCCN 2014049554. S2CID 191082736.

- Hilali, Asma (2010). "Le palimpseste de Ṣanʿā' et la canonisation du Coran: nouveaux éléments". Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz (in French). 21. Paris: Éditions de Boccard: 443–448. doi:10.3406/CCGG.2010.1742. JSTOR 24360016. S2CID 160655817. Retrieved 15 January 2021 – via Persée.fr.

- Sadeghi, Behnam; Goudarzi, Mohsen (2012). "Ṣan'ā' 1 and the Origins of the Qur'ān". Der Islam. 87 (1–2). Berlin: De Gruyter: 1–129. doi:10.1515/islam-2011-0025. S2CID 164120434.

- Sadeghi, Behnam; Bergmann, Uwe (2010). "The Codex of a Companion of the Prophet and the Qurʾān of the Prophet". Arabica. 57 (4). Leiden: Brill Publishers: 343–436. doi:10.1163/157005810X504518.

- Puin, Elisabeth (2011). "Ein früher Koranpalimpsest aus Ṣan'ā' (DAM 01-27.1) – Teil IV". Die Entstehung einer Weltreligion II. Hans Schiller. ISBN 978-3899303452.

- Puin, Elisabeth (2010). "Ein früher Koranpalimpsest aus Ṣan'ā' (DAM 01-27.1): Teil III: Ein nicht-'uṯmānischer Koran". Die Entstehung einer Weltreligion I: von der koranischen Bewegung zum Frühislam. Hans Schiller. ISBN 978-3899303186.

- Puin, Elisabeth (2009). "Ein früher Koranpalimpsest aus Ṣan'ā' (DAM 01-27.1): Teil II". Vom Koran zum Islam. Hans Schiller. ISBN 978-3899302691.

- Puin, Elisabeth (2008). "Ein früher Koranpalimpsest aus Ṣan'ā' (DAM 01-27.1)". Schlaglichter: Die beiden ersten islamischen Jahrhunderte. Hans Schiller. ISBN 978-3899302240.

- Hamdoun, Razan Ghassan (2004). The Qur'ānic Manuscripts In Ṣan'ā' From The First Century Hijra And The Preservation Of The Qur'ān. Archived from the original on 2013-11-03. Retrieved 2012-03-27.

- Taher, Abul (2000-08-08). "Querying the Koran". Guardian. Retrieved 2014-11-25.

- Lang, Jeffrey (2000). "Response on the article "What is the Koran"". The Atlantic Monthly. Archived from the original on March 1, 2001. Retrieved 2014-11-25.

- Lester, Toby (1999-01-01). "What is the Koran?". The Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved 2014-11-25.

External links

- Codex Ṣanʿāʾ – Inv. No. 01-27.1: Mid-1st Century Of Hijra, Islamic Awareness

- Early Qur'anic Manuscripts, Islamic Awareness

- The UNESCO Restoration Project

- Islamic Collections from the Museum, (pdf) UNESCO

- "A Qur’an written over the Qur’an – why making the effort?"

- Behnam, Sadeghi; Goudarzi, Mohsen (16 October 2017) [2012]. "Ṣan'ā'1 and the Origins of the Qur'ān" [Sanaa and the Origins of the Quran] (PDF). Stanford/Harvard Universities. Archive.org. Walter de Gruytur. ISSN 0021-1818. Retrieved 13 April 2019.