Senkaku Islands

| Disputed islands | |

|---|---|

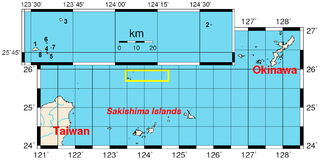

Location of the islands (yellow rectangle and inset) | |

| |

| Other names | Diaoyu Islands / Diaoyutai Islands / Pinnacle Islands |

| Geography | |

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 25°44′42″N 123°29′06″E / 25.74500°N 123.48500°E |

| Total islands | 5 + 3 rocks (reefs) |

| Major islands |

|

| Area | 7 km2 (2.7 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 383 m (1257 ft) |

| Administration | |

| City | Ishigaki, Okinawa |

| Claimed by | |

| Township | Toucheng Township, Yilan County, Taiwan |

| County | Yilan County, Taiwan |

| Senkaku Islands | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 釣魚島及其附屬島嶼 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 钓鱼岛及其附属岛屿 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Diaoyu Island and its affiliated islands | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Taiwanese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 釣魚臺列嶼 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 钓鱼台列屿 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Diaoyutai / Tiaoyutai Islands | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||

| Hiragana | せんかくしょとう | ||||||||||||

| Shinjitai | 尖閣諸島 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

The Senkaku Islands,[a] known as the Diaoyu Islands[b] in China and the Tiaoyutai Islands[c] in Taiwan, are a group of uninhabited islands in the East China Sea, administered by Japan. They were historically known in the Western world as the Pinnacle Islands. The islands are located northeast of Taiwan, east of China, west of Okinawa Island, and north of the southwestern end of the Ryukyu Islands.

The islands are the focus of a territorial dispute between Japan and China and between Japan and Taiwan.[9] China claims the discovery and ownership of the islands from the 14th century, while Japan maintained ownership of the islands from 1895 until its surrender at the end of World War II. The United States administered the islands as part of the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands from 1945 until 1972, when the islands returned to Japanese control under the Okinawa Reversion Agreement between the United States and Japan.[10] The discovery of potential undersea oil reserves in 1968 in the area was a catalyst for further interest in the disputed islands.[11][12][13][14][15] Despite the diplomatic stalemate between China and Taiwan, both governments agree that the islands are part of Taiwan as part of Toucheng Township in Yilan County. Japan administers and controls the Senkaku islands as part of the city of Ishigaki in Okinawa Prefecture. It does not acknowledge the claims of China nor Taiwan, but it has not allowed the Ishigaki administration to develop the islands.

As a result of the dispute, the public is largely barred from approaching the uninhabited islands, which are about a seven-hour boat ride from Ishigaki. Vessels from the Japan Coast Guard pursue Chinese ships crossing the maritime boundary in what one visiting journalist described in 2012 as "an almost cold war-style game of cat-and-mouse", and fishing and other civilian boats are prevented from getting too close to avoid a provocative incident.[16]

The Senkaku Islands are important nesting sites for seabirds, and are one of two remaining nesting sites in the world for the short-tailed albatross, alongside Tori-shima, Izu Islands.[17]

Names

The islands are referred to as the Senkaku Islands (尖閣諸島, Senkaku-shotō, variants: 尖閣群島 Senkaku-guntō[18] and 尖閣列島 Senkaku-rettō[19]) in Japanese. In mainland China, they are known as the Diaoyu Islands (Chinese: 钓鱼岛; pinyin: Diàoyúdǎo) or more fully "Diaoyu Dao and its affiliated islands" (Chinese: 钓鱼岛及其附属岛屿; pinyin: Diàoyúdǎo jí qí fùshǔ dǎoyǔ),[20] while in Taiwan they are called the Diaoyutai Islands or Tiaoyutai Islands[21][22][23][24] (Chinese: 釣魚臺列嶼; pinyin: Diàoyútái liè yǔ).[25][26][27][28] In Western sources, the historical English name Pinnacle Islands is occasionally still used when neutrality among the competing national claims is desirable.[29][30][31][32]

In Okinawan (northern Ryukyu), the islands are known as ʔiyukubajima (魚蒲葵島),[33] while their Yaeyama (southern Ryukyu) name is iigunkubajima.

Chinese records of these islands date back to as early as the 15th century when they were referred as Diaoyu in books such as Voyage with a Tail Wind (Chinese: 順風相送; pinyin: Shùnfēng Xiāngsòng) (1403) [34] and Record of the Imperial Envoy's Visit to Ryūkyū (Chinese: 使琉球錄; pinyin: Shǐ Liúqiú Lù) (1534).[citation needed] Adopted by the Chinese Imperial Map of the Ming Dynasty, the Chinese name for the island group (Diaoyu) and the Japanese name for the main island (Uotsuri) both mean "fishing".

History

Early history

Historically, the Chinese had used the uninhabited islands as navigational markers in making the voyage to the Ryukyu Kingdom upon commencement of diplomatic missions to the kingdom, "resetting the compass at a particular isle in order to reach the next one".[35]

The first published description of the islands in Europe appears in a book imported by Isaac Titsingh in 1796. His small library of Japanese books included Sangoku Tsūran Zusetsu (三國通覧圖說, An Illustrated Description of Three Countries) by Hayashi Shihei.[36] This text, which was published in Japan in 1785, described the Ryūkyū Kingdom.[37] Hayashi followed convention in giving the islands their Chinese names in his map in the text, where he coloured them in the same pink as China.[38]

In 1832, the Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland supported the posthumous abridged publication of Titsingh's French translation.[39]

The name, "Pinnacle Isles" was first used by James Colnett, who charted them during his 1789–1791 voyage in the Argonaut.[40] William Robert Broughton sailed past them in November 1797 during his voyage of discovery to the North Pacific in HMS Providence, and referred to Diaoyu Island/Uotsuri Island as "Peaks Island".[41] Reference was made to the islands in Edward Belcher's 1848 account of the voyages of HMS Sammarang.[42] Captain Belcher remarked that "the names assigned in this region have been too hastily admitted."[43] Belcher reported anchoring off Pinnacle Island in March 1845.[44]

In the 1870s and 1880s, the English name Pinnacle Islands was used by the British navy for the rocks adjacent to the largest island Uotsuri-shima / Diaoyu Dao (then called 和平嶼; hô-pîng-sū; 'Peace Island in Hokkien'); Kuba-shima / Huangwei Yu (then called Ti-a-usu); and Taishō-tō / Chiwei Yu.[45]

A Japanese navy record issued in 1886 first started to identify the islets using equivalents of the Chinese and English terms employed by the British. The name "Senkaku Retto" is not found in any Japanese historical document before 1900 (the term "Senkaku Gunto" began being used in the late 19th century), and first appeared in print in a geography journal published in 1900. It was derived from a translation of the English name Pinnacle Islands into a Sinicized Japanese term "Sento Shoto" (as opposed to "Senkaku Retto", i.e., the term used by the Japanese today), which has the same meaning.[46]

The collective use of the name "Diaoyutai" to denote the entire group began with the advent of the controversy in the 1970s.[47]

Control of the islands by Japan and the US

As the uninhabited islets were historically used as maritime navigational markers, they were never subjected to administrative control other than the recording of the geographical positions on maps, descriptions in official records of Chinese missions to the Ryukyu Kingdom, etc.[35]

The Japanese central government incorporated the islands into Okinawa Prefecture in January 1895 while still fighting China in the First Sino-Japanese War.[38] Around 1900, Japanese entrepreneur Koga Tatsushirō (古賀 辰四郎) constructed a bonito fish processing plant on the islands, employing over 200 workers. The business failed around 1940 and the islands have remained deserted ever since.[48] In the 1970s, Koga Tatsushirō's son Zenji Koga and Zenji's wife Hanako sold four islets to the Kurihara family of Saitama Prefecture. Kunioki Kurihara[49] owned Uotsuri, Kita-Kojima, and Minami-Kojima. Kunioki's sister owned Kuba.[50]

The islands came under US government occupation in 1945 after the surrender of Japan ended World War II.[48] In 1969, the United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (ECAFE) identified potential oil and gas reserves in the vicinity of the Senkaku Islands.[51] In 1971, the Okinawa Reversion Treaty passed the U.S. Senate, returning the islands to Japanese control in 1972.[52] Also in 1972, the Republic of China government and People's Republic of China government officially began to declare ownership of the islands.[53]

Since 1972, when the islands reverted to Japanese government control, the government of Ishigaki has been given civic authority over the territory. The Japanese central government, however, has prohibited Ishigaki from surveying or developing the islands.[48][54]

In 1978, a Japanese political group constructed the first lighthouse on Uotsuri island and grazed two goats. Goats have since proliferated and affected the island's vegetation.[55]

In 1979 an official delegation from the Japanese government composed of 50 academics, government officials from the Foreign and Transport ministries, officials from the now-defunct Okinawa Development Agency, and Hiroyuki Kurihara, visited the islands and camped on Uotsuri for about four weeks. The delegation surveyed the local ecosystem, finding moles and sheep, studied the local marine life, and examined whether the islands would support human habitation.[50]

In 1988, a Japanese political group reconstructed a lighthouse on Uotsuri Island.[56]

In 2005, a Japanese fisherman who owned a lighthouse at Uotsuri Island expressed his intention to relinquish the ownership of the lighthouse, and the lighthouse became a national property pursuant to the provisions of the Civil Code of Japan. Since then, the Japan Coast Guard has maintained and managed the Uotsuri lighthouse.[56]

From 2002 to 2012, the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications paid the Kurihara family ¥25 million a year to rent Uotsuri, Minami-Kojima and Kita-Kojima. Japan's Ministry of Defense rents Kuba island for an undisclosed amount. Kuba is used by the U.S. military as a practice aircraft bombing range. Japan's central government completely owns Taisho island.[50][57]

The reaction of the Kan Cabinet to the September 2010 Senkaku boat collision incident was seen by former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe as "a very foolish move" and "frighteningly naive".[58][59]

On December 17, 2010, the city of Ishigaki designated January 14 as "Pioneering Day" to commemorate Japan's 1895 incorporation of the Senkaku Islands. China condemned Ishigaki's actions.[60]

In May 2012, both the Tokyo Metropolitan and Japanese central governments announced plans to negotiate purchase of Uotsuri, Kita-Kojima, and Minami-Kojima from the Kurihara family,[50] and on September 11, 2012, the Japanese government nationalized its control over Minami-kojima, Kita-kojima, and Uotsuri islands by purchasing them from the Kurihara family for ¥2.05 billion.[61] China's Foreign Ministry objected saying Beijing would not "sit back and watch its territorial sovereignty violated."[62]

In 2014, Japan constructed a lighthouse and wharf featuring Japanese flag insignia on the islets.[63]

Geography

The island group are known to consist of five uninhabited islets and three barren rocks.[64] China has identified and named as many as 71 islets that belong to this group after the Japanese Cabinet released names of 39 uninhabited islands.[65][66]

These minor features in the East China Sea are located approximately 120 nautical miles northeast of Taiwan, 200 nautical miles east of the Chinese mainland and 200 nautical miles southwest of the Japanese island of Okinawa.[67]

According to one visitor, Uotsuri-shima, the largest of the islands, consists of a pair of rocky gray mountains with steep, boulder-strewn slopes rising almost straight from the water's edge. Other, nearby islands were described as large rocks covered by low vegetation.[16]

In ascending order of distances, the island cluster is located:

- 140 km (76 nmi; 87 mi) east of Pengjia Islet, Republic of China (Taiwan)[68]

- 170 km (92 nmi; 110 mi) north of Ishigaki Island, Japan

- 186 km (100 nmi; 116 mi) northeast of Keelung, Republic of China (Taiwan)

- 410 km (220 nmi; 250 mi) west of Okinawa Island, Japan

| No. | Japanese name[69] | Republic of China name[70][71] | China (PRC) name[72][73] | Coordinates | Area (km2)[71] | Highest elevation (m) | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Uotsuri Island (魚釣島)[74] | 釣魚臺[75] / 釣魚台 Diaoyutai POJ: Tiò-hî-tâi[76] |

Diaoyu Dao (钓鱼岛/釣魚島) | 25°44′36″N 123°28′33″E / 25.74333°N 123.47583°E | 4.32 | 383 |  |

| 2 | Taisho Island (大正島)[77] | 赤尾嶼 Chiwei Isle | Chiwei Yu (赤尾屿/赤尾嶼) | 25°55′21″N 124°33′31″E / 25.92250°N 124.55861°E | 0.0609 | 75 |  |

| 3 | Kuba Island (久場島)[78] | 黃尾嶼 Huangwei Isle | Huangwei Yu (黄尾屿/黄尾嶼) | 25°55′26″N 123°40′55″E / 25.92389°N 123.68194°E | 1.08 | 117 |  |

| 4 | Kitakojima Island (北小島)[79] | 北小島 Beixiao Island | Beixiao Dao (北小岛/北小島) | 25°43′47″N 123°32′29″E / 25.72972°N 123.54139°E | 0.3267 | 135 |  |

| 5 | Minamikojima Island (南小島)[80] | 南小島 Nanxiao Island | Nanxiao Dao (南小岛/南小島) | 25°43′25″N 123°33′00″E / 25.72361°N 123.55000°E | 0.4592 | 149 | |

| 6 | Okinokitaiwa Island (沖ノ北岩)[81] | 沖北岩 Chongbeiyan | Bei Yu (北屿/大北小岛/大北小島) | 25°46′45″N 123°32′30″E / 25.77917°N 123.54167°E | 0.0183 | nominal |  |

| 7 | Okinominamiiwa Island (沖ノ南岩)[82] | 沖南岩 Chongnanyan | Nan Yu (南屿/大南小岛/大南小島/南岩) | 25°45′19″N 123°34′01″E / 25.75528°N 123.56694°E | 0.0048 | nominal |  |

| 8 | Tobise Island (飛瀬)[83] | 飛瀨 Feilai | Fei Yu (飞屿/飞礁岩/飛礁岩) | 25°44′08″N 123°30′22″E / 25.73556°N 123.50611°E | 0.0008 | nominal |  |

The depth of the surrounding waters of the continental shelf is approximately 100–150 metres (330–490 ft) except for the Okinawa Trough on the south.[84] The shelf is shallow enough that the western islands were likely connected to the mainland during the Last Glacial Period.[85]

Geology

Uotsuri, Kitakojima, Minamikojima and surrounding islets are sedimentary in origin, predominantly consisting of probably Miocene aged sandstone and sandstone-conglomerate, with subordinate conglomerate, coal seams up to 10 centimetres (3.9 in) thick, and rare siltstone beds. The sedimentary strata have around 300 metres (980 ft) of exposed thickness at Uotsuri, and have SW-NE, EW and NW-SE strikes, with a general inclination of a dip of less than 20 degrees towards the North.[86] These strata are intruded by sheets of Mio-Pliocene porphyritic hornblende diorite, and are fringed by recent coral outcrops and surface talus deposits. Kuba and Taisho are volcanic in origin, with Kuba comprising "pyroxene andesite, lava, volcanic bombs, pumice, limestone, and other rocky material" and Taisho is thought to be consist of "andesite, tuff breccia, and tuffaceous sandstone".[87]

Wildlife

Plants

Permission for collecting herbs on three of the islands was recorded in an Imperial Chinese edict of 1893.[88]

Several floral surveys have been conducted on the Senkaku islands,[89][90] with a 1980 survey finding that Uotsuri had 339 species of plants. These ecological communities varied based on altitude, with the communities being divided into windswept mountaintop vegetation with Podocarpus macrophyllus trees, with the understory including Liriope muscari and Rhaphiolepis umbellata, inclined high forest including the palms Livistona chinensis and Arenga engleri, lowland windswept shrub forest including Ficus microcarpa and Planchonella obovata, and seashore plants. Minamikojima was much less diverse, and dominated by grasses, while Kitakojima only had sparse plant life.[91] Kuba has a forest near the crater, which includes a variety of flora including Ceodes umbellifera, Macaranga tanarius, Ficus benjamina, Diospyros maritima, Trema orientalis, Machilus thunbergii, and Livistona subglobosa, with forest floor plants being sparse.[90]

Animals

In an account by Hisashi Kuroiwa in 1900, it was noted the large number of birds present on the islands, tens of thousands of short-tailed and black-footed albatross would flock on Uotsuri-shima, in the colder months, while hundreds of thousands of sooty tern and brown noddy would descend on Kitakojima and Minamikojima in the warmer months. He also described the air of Uotsuri as swarming with bluebottle flies and mosquitoes. In the same year, an account by Miyajima Mikinosuke, surveying Kuba Island, noted the presence of whimbrel, Von Schrenck's bittern, the streaked shearwater, and the brown booby. Mikinosuke also noted the large number of chickens and feral cats on the island, with dozens of cats descending on the seabirds at night.[92] Kitakojima and Minamikojima are one of only two significant breeding places of the rare short-tailed albatross (Phoebastria albatrus).[17] The islands have been recognised as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International.[93]

Uotsuri-shima, the largest island, has a number of endemic species such as the Senkaku mole (Mogera uchidai) and Okinawa-kuro-oo-ari ant. Due to the introduction of domestic goats to the island in 1978, the Senkaku mole is now an endangered species.[94] The striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius) has also been noted to be present on Uotsuri. Surveys from 1900 to 1953 and noted the presence of the Asian house shrew, black rats and fruit bats but these were not noted in more recent surveys.[89][91]

Six species of reptile have been recorded from the islands, including Gekko hokouensis (Uotsuri, Minami) Eumeces elegans (Uotsuri, Minami), an indeterminate species of Scincella (Uotsuri) Ramphotyphlops braminus (Uotsuri) Elaphe carinata (Uotsuri) and Dinodon rufozonatus (Uotsuri).[85]

Rich marine biodiversity adjacent to the islands has been recognized but poorly studied. Seemingly, varieties of larger fish and animals inhabit or migrate through the area, including tunas, sharks, marlins, critically endangered hawksbill sea turtles, dolphins, pilot whales, sperm whales, and humpback whales.[95]

Sovereignty dispute

Territorial sovereignty over the islands and the maritime boundaries around them are disputed between the People's Republic of China, the Republic of China, and Japan.

The People's Republic and Republic of China claim that the islands have been a part of Chinese territory since at least 1534. China acknowledges that Japan took control of the islands in 1894–1895 during the first Sino-Japanese War, through the signature of the Treaty of Shimonoseki. China asserts that the Potsdam Declaration required that Japan relinquish control of all islands except for "the islands of Honshū, Hokkaidō, Kyūshū, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine", and China states that this means control of the islands should pass to Republic of China, which was part of China at the time of the first Sino-Japanese War as well as of the San Francisco Peace Treaty. Both the People's Republic of China (PRC)[96] and the Republic of China (ROC)[97] respectively separately claim sovereignty based on arguments that include the following points:

- Discovery and early recording in maps and travelogues.[98]

- The islands being China's frontier off-shore defence against wokou (Japanese pirates) during the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368–1911).

- A Chinese map of Asia, as well as the Sangoku Tsūran Zusetsu map[97] compiled by Japanese cartographer Hayashi Shihei[99] in the 18th century,[98] showing the islands as a part of China.[98][100]

- Japan taking control of the islands in 1895 at the same time as the First Sino-Japanese War was happening. Furthermore, correspondence between Foreign Minister Inoue and Interior Minister Yamagata in 1885, warned against the erection of national markers and developing their land to avoid Qing Dynasty suspicions.[98][100][101]

- The Potsdam Declaration stating that "Japanese sovereignty shall be limited to the islands of Honshū, Hokkaidō, Kyūshū, Shikoku and such minor islands as we determine", and "we" referred to the victors of the Second World War who met at Potsdam and Japan's acceptance of the terms of the Declaration when it surrendered.[100][102][103]

- China's formal protest of the 1971 US transfer of control to Japan.[104]

Japan does not accept that there is a dispute, asserting that the islands are an integral part of Japan.[105] Japan has rejected claims that the islands were under China's control prior to 1895, and that these islands were contemplated by the Potsdam Declaration or affected by the San Francisco Peace Treaty.[106]

The existence of the back-arc basin complicates descriptive issues. According to Professor Ji Guoxing of the Asia-Pacific Department at Shanghai Institute for International Studies,

- China's interpretation of the geography is that

...the Okinawa Trough proves that the continental shelves of China and Japan are not connected, that the Trough serves as the boundary between them, and that the Trough should not be ignored ....[107]

- Japan's interpretation of the geography is that

...the trough is just an incidental depression in a continuous continental margin between the two countries ... [and] the trough should be ignored ....[107]

The stance given by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs is that the Senkaku Islands are clearly an inherent territory of Japan, in light of historical facts and based upon international law, and the Senkaku Islands are under the valid control of Japan. They also state "there exists no issue of territorial sovereignty to be resolved concerning the Senkaku Islands."[108][109] The following points are given:

- The islands had been uninhabited and showed no trace of having been under the control of China prior to 1895.[110]

- The purposes of maps and the intentions behind their creators can vary significantly, and the mere existence of an ancient map does not substantiate claims of territorial sovereignty. The map (1785) cited by China from Hayashi Shihei does not provide evidence that the creator's coloring was intended to indicate an understanding of territorial sovereignty. This map depicts Taiwan as being only about one-third the size of Okinawa's main island and is colored differently from that of mainland China. This suggests that the creator did not possess accurate knowledge.[111]

- The islands were neither part of Taiwan nor part of the Pescadores Islands, which were ceded to Japan by the Qing Dynasty of China in Article II of the May 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki,[110] thus were not renounced by Japan under Article II of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, which serves as the international law addressing the aftermath of WW2.[112]

- A resident of Okinawa Prefecture who had been engaging in activities such as fishery around the Senkaku Islands since around 1884 made an application for the lease of the islands, and approval was granted by the Meiji Government in 1896. After this approval, he sent a total of 248 workers to those islands and ran the following businesses: constructing piers,[113] collecting bird feathers, manufacturing dried bonito, collecting coral, raising cattle, manufacturing canned goods and collecting mineral phosphate guano (bird manure for fuel use). The fact that the Meiji Government gave approval concerning the use of the Senkaku Islands to an individual, who in turn was able to openly run these businesses mentioned above based on the approval, demonstrates Japan's valid control over the Islands.[114]

- In May 1920, a thank-you letter from the Republic of China's consulate in Nagasaki regarding the rescue of Chinese fishermen in distress near the Senkaku Islands by Japanese fishermen included the notation "Senkaku Islands, Yaeyama District, Okinawa Prefecture, Empire of Japan."[111]

- Though the islands were controlled by the United States as an occupying power between 1945 and 1972, Japan has since 1972 exercised administration over the islands.

- In 1953, the official Chinese newspaper People's Daily published an article that explicitly stated that the Ryukyu Islands consist of seven island groups, including the Senkaku Islands. Additionally, in the world atlas published by the China Map Press in 1958 (reprinted in 1960), these islands were clearly referred to as the "Senkaku Islands" and considered part of Okinawa.[115]

- Republic of China and People Republic of China only started claiming ownership of the islands in 1971, following a May 1969 United Nations report that a large oil and gas reserve may exist under the seabed near the islands.[116][111]

In 2012 the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs created a website in support of its claims;[117] in late 2014 the National Marine Data and Information Service, a department under the State Oceanic Administration of People's Republic of China created a website of its own to support its claims.[118][119] In 2016, Chinese fishing, Coast Guard and other vessels were entering the territorial waters around the islands almost daily and in August 2016 the Japanese foreign minister Fumio Kishida reportedly told China's foreign minister Wang Yi "that the activity represented an escalation of tensions" according to Japanese sources. It was the first meeting of the top diplomats since the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling against China's South China Sea claims[120][121] and was coincident with a three-party meeting (including South Korea) relative to a North Korean submarine-launched missile in the Sea of Japan.[122]

On 22 June 2020, the Ishigaki City Council voted to change the name of the area containing the Senkaku Islands from "Tonoshiro" to "Tonoshiro Senkaku".[123] Republic of China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded that the islands belong to Republic of China, and any moves to deny this fact are invalid.[124] The Taiwanese government and the opposition KMT party also condemned the council's move, saying the Islands are ROC territory and the nation would not give up even "an inch" of its sovereignty.[125]

In popular culture

Diaoyu Islands: The Truth is a documentary film produced by Chris D. Nebe and J.J. Osbun of Monarex Hollywood Corporation and directed by Chris D. Nebe. Nebe calls on the Japanese Government to cede the islands to China, asserting that Japan has no justifiable claim to the islands, and that the United States of America has turned a blind eye in Japan's favor due to the need of the United States to have a strong ally between it and China. Reception of the film was positive in Chinese media, while the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's Correspondents Report called Nebe a 'Chinese propagandist' in 2014.[126]

In 2018 the National Museum of Territory and Sovereignty (currently located in the Toranomon Mitsui Building, Chiyoda, Tokyo) was established by the Japanese government to raise public awareness of Japanese territorial rights issues concerning the Senkaku Islands, as well as issues concerning territorial claims to Takeshima and southernmost Kuril Islands.[127]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ The Guardian (November 23, 2013). "China imposes airspace restrictions over Japan-controlled Senkaku islands". TheGuardian.com. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

China imposes airspace restrictions over Japan-controlled Senkaku islands

- ^ France24 (November 27, 2013). "US defies China to fly over disputed Senkaku islands". Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

The zone covers the Tokyo-controlled Senkaku islands

{cite web}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ 釣魚臺列嶼相關文獻 (in Chinese). Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Taiwan). Archived from the original on October 24, 2013.

- ^ 地理位置圖. 宜蘭縣頭城鎮公所 Toucheng Township Office (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Archived from the original on July 7, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

另轄兩小島(龜山島及龜卵嶼)及一群島(釣魚臺列嶼)。

- ^ 我們的釣魚臺 (in Chinese). Central News Agency (Republic of China). Archived from the original on January 14, 2019. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ 中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 (September 25, 2012). 《钓鱼岛是中国的固有领土》白皮书 (in Chinese). 新华社. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012.

1871年......将钓鱼岛列入海防冲要,隶属台湾府噶玛兰厅(今台湾省宜兰县)管辖。

- ^ National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, Senkaku-guntō, Japan Archived June 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, Senkaku-rettō, Japan Archived April 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ McDorman, Ted L. (2005). "Central Pacific and East Asian Maritime Boundaries" in International Maritime Boundaries, Vol. 5, pp. 3441., p. 3441, at Google Books

- ^ Lee, Seokwoo. (2002). Territorial Disputes Among Japan, China and Taiwan Concerning the Senkaku Islands, pp. 10–13., p. 10, at Google Books

- ^ Lee, Seokwoo (2002). Territorial Disputes among Japan, China and Taiwan concerning the Senkaku Islands (Boundary & Territory Briefing Vol.3 No.7). IBRU. p. 6. ISBN 1897643500.

The question of the disputed Senkaku Islands remained relatively dormant throughout the 1950s and 1960s, probably because these small uninhabited islands held little interest for the three claimants. The Senkaku Islands issue was not raised until the Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (hereinafter 'ECAFE') of the United Nations Economic and Social Council suggested the possible existence of large hydrocarbon deposit in the waters off the Senkaku Islands. ... This development prompted vehement statements and counter-statements among the claimants.

- ^ Pan, Junwu (2009). Toward a New Framework for Peaceful Settlement of China's Territorial and Boundary Disputes. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 140. ISBN 978-9004174283. Archived from the original on August 27, 2024. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

Obviously, primarily regional interests in oil and gas resources that may lie under the seas drive the two major disputes. The Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands issue did not re-surface until 1969 when the Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East of the United Nations Economic and Social Council reported that the continental shelf of the East China "might contain one of the most prolific oil and gas reservoirs of the world, possibly comparing favourably with the Persian Gulf." Then both China and Japan had high expectations that there might be large hydrocarbon deposits in the waters off the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands. The Law of the Sea at that time emphasized the theory of natural prolongation in determining continental shelf jurisdiction. Ownership of the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands would permit the owner to a large area of the continental shelf that may have rich sources of gas and oil. Such a dispute is obviously related to the awakening interest by the world's states in developing offshore energy resources to meet the demand of their economies.

- ^ Takamine, Tsukasa (2012). Japan's Development Aid to China, Volume 200: The Long-running Foreign Policy of Engagement. Routledge. p. 129. ISBN 978-0415352031. Archived from the original on August 27, 2024. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

The islands had temporarily come under American control after the Second World War, but the sovereignty over the islands, was handed over to Japan in 1972 with the reversion of Okinawa.However, the PRC and ROC governments both made a territorial claim to the Senkaku Islands, soon after the United Nation Economic Commission issued in 1969 a report suggesting considerable reserve of submarine oil and gas resources around the islands.

- ^ Drifte, Reinhard (2012). Japan's Security Relations with China Since 1989: From Balancing to Bandwagoning?. Routledge. p. 49. ISBN 978-1134406678. Archived from the original on August 27, 2024. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

The dispute surfaced with the publication of a seismic survey report under the auspices of the UN Economic Commission for Asia and the Far East (ECSFE) in 1968, which mentioned the possibility of huge oil and gas reserves in the area; this was confirmed by a Japanese report in 1969. Greg Austin mentions that Beijing started its claim to the Senkaku Islands for the first time in 1970, after Japanese government protested to the government in Taiwan about its allocation of oil concessions in the East China Sea, including the area of the Senkaku Islands.

- ^ Lee, Seokwoo (2002). Territorial Disputes among Japan, China and Taiwan concerning the Senkaku Islands (Boundary & Territory Briefing Vol.3 No.7). IBRU. pp. 10–11. ISBN 1897643500. Archived from the original on August 27, 2024. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

For a long time following the entry into force of the San Francisco Peace Treaty China/Taiwan raised no objection to the fact that the Senkaku Islands were included in the area placed under US administration in accordance with the provisions of Article of the treaty, and USCAP No. 27. In fact, neither China nor Taiwan had taken up the question of sovereignty over the islands until the latter half of 1970 when evidence relating to the existence of oil resources deposited in the East China Sea surfaced. All this clearly indicates that China/Taiwan had not regarded the Senkaku Islands as a part of Taiwan. Thus, for Japan, none of the alleged historical, geographical and geological arguments set forth by China/Taiwan are acceptable as valid under international law to substantiate China's territorial claim over the Senkaku Islands.

- ^ a b Fackler, Martin (September 22, 2012). "In Shark-Infested Waters, Resolve of Two Giants is Tested". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 27, 2024. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ a b "Albatrosses Residing on the Senkaku Islands (1979: Former Okinawa Development Agency)". Review of Island Studies. Archived from the original on August 27, 2024. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, Senkaku-guntō, Japan Archived June 30, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, Senkaku-rettō, Japan Archived April 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ "Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying's Remarks on the Japanese Government Opening a Link about Diaoyu Dao on the Official Cabinet Website". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the People's Republic of China. August 28, 2015. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ "The ROC government reiterates its sovereignty over the Tiaoyutai Islands". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on November 5, 2020. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

According to a report appearing in the Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun on January 1, 2003, the Japanese government began leasing three uninhabited islands (Kita-kojima, Minami-kojima and Uotsurishima) out of the five islets that comprise the Tiaoyutai Islands (known as the "Senkaku Islands" in Japan) in October 2002 at the rate of 22 million Japanese yen annually. The ROC's Ministry of Foreign Affairs has instructed the Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office in Japan to ascertain the current position of the Japanese government on this issue and to express the ROC's solemn position regarding its claim to sovereignty over the Tiaoyutai Islands.

- ^ Jesse Johnson (July 27, 2020). "China's 100-day push near Senkaku Islands comes at unsettling time for Sino-Japanese ties". Japan Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

There are few better examples that underscore Japan's complicated relationship with China than the uninhabited but strategically positioned Senkakus, which are also claimed by China, which calls them Diaoyu, as well as Taiwan, which calls them Tiaoyutai.

- ^ Harold C. Hinton (1980). The China Sea: The American Stake in its Future. National Strategy Information Center. p. 13, 14, 25, 26. ISBN 0-87855-871-3 – via Internet Archive.

The other territorial dispute in the East China Sea is considerably more complicated and more serious. It relates to a group of eight small uninhabited islands known in China as the Tiaoyutai and in Japan as the Senkaku and claimed by Japan and both Chinas; they lie on the edge of the continental shelf about 120 miles northeast of Taiwan.

- ^ "Media Reaction: Cross-Strait Talks, Taiwan-Japan Dispute, U.S. Global Influence". United States Department of State. 2008 – via Internet Archive.

A separate "Liberty Times" column discussed the recent dispute between Taiwan and Japan over the Tiaoyutai Islands and urged the Ma administration to seek to form an equilateral triangular relationship with the United States, Japan and China, so that no side will feel threatened of will overpower the other.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs Taiwan. "the Republic of China's Sovereignty Claims over the Diaoyutai Islands and the East China Sea Peace Initiative". www.mofa.gov.tw. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved November 24, 2013.

- ^ "Diaoyutai tensions stoked by arrival of China coast guard". www.taipeitimes.com. August 17, 2013. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ "China preparing for Diaoyutai conflict: expert". www.chinapost.com.tw. November 24, 2013. Archived from the original on January 25, 2014.

- ^ "The Republic of China's Sovereignty Claims over the Diaoyutai Islands and the East China Sea Peace Initiative". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Taiwan (Taiwan). September 5, 2013. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ Lai 2013, p. 208 cites Hagstrom 2005; "The islands are also called 'Pinnacle Islands' for convenience and neutrality sake by Western scholars"

- ^ The Diaoyutaiisenkaku Islands Dispute: its History and an Analysis of the Ownership Claims of the P.R.C., R.O.C., and Japan Archived June 24, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Occasional Papers/Reprints Series in Contemporary Asian Studies, Nr 3 – 1999 (152), p.13

- ^ What's in a name? Archived July 8, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, BusinessMirror: "The disputed islands East China Sea are called the Senkaku Islands by Japan, Diaoyu Islands in China and the Diaoyutai Islands by the government of Taiwan. In the West, these rocks are called the Pinnacle Islands as a loose translation of the Japanese name."

- ^ Japan's Territorial Disputes Archived July 8, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, American Diplomacy: "The Chinese call them the Diaoyu Islands, and on foreign maps in the past they have been called the Pinnacle Islands."

- ^ Okinawago jiten (in Japanese). Kokuritsu Kokugo Kenkyūjo, 国立国語研究所. Tōkyō: Zaimushō Insatsukyoku. March 30, 2001. p. 549. ISBN 4-17-149000-6. OCLC 47773506.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Title: Liang zhong hai dao zhen jing / [Xiang Da jiao zhu].Imprint: Beijing : Zhonghua shu ju : Xin hua shu dian Beijing fa xing suo fa xing, 2000 reprint edition. Contents: Shun feng xiang song—Zhi nan zheng fa. (順風相送--指南正法). ISBN 7-101-02025-9. pp96 and pp253 Archived July 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The full text is available at wikisource Archived June 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Suganuma, p. 49., p. 49-54, at Google Books

- ^ WorldCat, Sangoku Tsūran Zusetsu Archived February 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine; alternate romaji Sankoku Tsūran Zusetsu Archived October 6, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cullen, Louis M. (2003). A History of Japan, 1582–1941: Internal and External Worlds, p. 137., p. 137, at Google Books

- ^ a b "The Senkaku or Diaoyu Islands: Narrative of an empty space". The Economist. No. Christmas Specials 2012. London: Economist Group. December 22, 2012. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ Klaproth, Julius. (1832). San kokf tsou ran to sets, ou Aperçu général des trois royaumes, pp. 169–180., p. i, at Google Books

- ^ "Pinnacle Rock in Latitude 29°40′ and Longitude 132° E. of London... This Navigation is no ways dangereous were you sure of your Latitude and to make Pinnicle Isle". James Colnett, The Journal ... aboard the Argonaut from April 26, 1789 to Nov. 3, 1791, ed. with introd. and notes by F. W. Howay, Toronto, Champlain Society Vol. 26, 1940, p. 47.

- ^ William Robert Broughton, William Robert Broughton's Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific, 1795–1798, edited by Andrew David; with an introduction by Barry Gough, Ashgate for the Hakluyt Society, Farnham, England; Burlington, VT, 2010, p. 202.

- ^ Suganuma, Unryu. (2001). Sovereign Rights and Territorial Space in Sino-Japanese Relations, at Google Books

- ^ Belcher, Edward. (1848). Narrative of the Voyage of H.M.S. Samarang, Vol. I, pp. 315., p. 315, at Google Books; Belcher, Vol. II, pp. 572–574., p. 572, at Google Books

- ^ Belcher, Vol. I, at Google Books; excerpt at p. 317, "On the 16th, we endeavoured to obtain observations on Tia-usu; a landing was effected, but the absence of sun prevented our obtaining satisfactory observations, and bad weather coming on hastened our departure. This group, comprehending hô-pîng-san (和平山, "Peace Island", Uotsuri-shima), Pinnacle Rocks, and Tias-usu (Kuba-shima), form a triangle, of which the hypothenuse, or distance between Hoa-pin-san and Tia-usu, extends about fourteen miles, and that between Hoa-pinsan and the Southern Pinnacle, about two miles."

- ^ Suganuma, p. 90., p. 90, at Google Books; Jarrad, Frederick W. (1873). The China Sea Directory, Vol. IV, pp. 141–142., p. 141, at Google Books

- ^ Suganuma, p. 91., p. 91-4, at Google Books

- ^ Koo, Min Gyo (2009). Disputes and Maritime Regime Building in East Asia, p. 103 n2. Archived July 8, 2023, at the Wayback Machine citing Park (1973) "Oil under Troubled Waters: The Northeast Asia Seabed Controversy", 14 HILJ (Harvard International Law Journal) 212, 248–249; also Park, Choon-Ho (1972). Continental Shelf Issues in the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea. Kingston, Rhode Island: Law of the Sea Institute, pp. 1–64.

- ^ a b c d Kaneko, Maya, (Kyodo News) "Ishigaki fishermen fret over Senkaku encroachment Archived December 27, 2012, at archive.today", Japan Times, December 8, 2010, p. 3.

- ^ "BBC News – Japan confirms disputed islands purchase plan". bbc.co.uk. 2012. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

Kunioki Kurihara

- ^ a b c d Ito, Masami, "Owner OK with metro bid to buy disputed Senkaku Islands", Japan Times, May 18, 2012, pp. 1–2

- ^ "Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands". Globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on July 5, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2005.

- ^ Finney, John W. "Senate Endorses Okinawa Treaty; Votes 84 to 6 for Island's Return to Japan" Archived October 27, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times. November 11, 1971.

- ^ Kyodo News, "Senkaku purchase bid made official Archived September 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine", Japan Times, September 11, 2012, p. 2

- ^ Ito, Masami, "Jurisdiction over remote Senkakus comes with hot-button dangers Archived May 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine", Japan Times, May 18, 2012, p. 1

- ^ The Problem of Feral Goats on Uotsuri-jima in the Senkuku Islands and Appeals for Countermeasures to Resolve the Problem. Archived July 5, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, Japanese Journal of Conservation Ecology 8, p.90. Yasushi Yokohata, Laboratory of Environmental Biology, Faculty of Education, Toyama University. 2003.

- ^ a b 4. Start managing the "Uotsuri Island Lighthouse" of the Senkaku Islands Japan Coast Guard Annual Report 2005

- ^ Hongo, Jun, "Tokyo's intentions for Senkaku islets Archived November 1, 2012, at the Wayback Machine", Japan Times, April 19, 2012, p. 2.

- ^ Abe, Shinzo (October 15, 2010). "Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe on U.S.-Japanese Relations" (PDF). No. The Capital Hilton Washington, DC. Hudson Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Abe, Shinzo (October 15, 2010). "U.S.-Japan Relations". National Cable Satellite Corporation. C-SPAN. Archived from the original on August 27, 2024. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Agence France-Presse, "Senkaku memorial day riles China Archived July 20, 2012, at archive.today", Japan Times, December 19, 2010, p. 1. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ Fackler, Martin (September 6, 2012). "Japan Said to Have Tentative Deal to Buy 3 Disputed Islands from Private Owners". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ "Japan says it will purchase disputed islands from private owner, angering China". Washington Post. AP. September 10, 2012. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2012.

- ^ Kyodo News, "Taiwan activists threaten to land on Senkakus if Japan doesn't remove facilities Archived November 16, 2022, at the Wayback Machine", Japan Times, 2 March 2015

- ^ "How uninhabited islands soured China-Japan ties". BBC News. September 17, 2010. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved June 20, 2018.

- ^ China announces geographic codes for Diaoyu Islands

- ^ "China releases official names of disputed islands". Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ^ UC Berkeley: UC Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation; retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrals (ACAP) Archived April 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Breeding site details: Agincourt/P'eng-chia-Hsu Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Senkaku Islands" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. March 2014. p. 2. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

Kuba Island Taisho Island Okinokitaiwa Island Uotsuri Island Okinominamiiwa Island Tobise Island Kitakojima Island Minamikojima Island

- ^ 宜蘭縣土地段名代碼表 (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Department of Land Administration. October 31, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

地政事務所名稱(代碼) 宜蘭(GB) 鄉鎮市區名稱(代碼) 頭城鎮(02){...}段 小段 代碼 備註{...}釣魚台 0568 赤尾嶼 0569 黃尾嶼 0570 北小島 0571{...}南小島 0572

- ^ a b 05-19 臺灣島嶼面積 [Location and Area of Islands in Taiwan]. Ministry of the Interior (in Chinese (Taiwan) and English). Retrieved October 20, 2019.

縣市別 Locality 島嶼名稱 位置 Location 面積(平方公里) (1) 經度 緯度 Name of Islands Longitude Latitude Area (Km2){...}宜蘭縣 Yilan County{...}釣魚臺 Diaoyutai 123°32′48〞~123°30′27〞 25°45′26〞~25°46′31〞 4.3838 黃尾嶼 Huangwei Isle 123°41′56〞~123°41′08〞 25°55′45〞~25°56′21〞 0.9091 赤尾嶼 Chiwei Isle 124°34′09〞~124°33′50〞 25°53′54〞~25°54′06〞 0.0609 北小島 Beixiao Island 123°35′48〞~123°35′15〞 25°44′45〞~25°45′21〞 0.3267 南小島 Nanxiao Island 123°36′29〞~123°35′36〞 25°44′25〞~25°44′47〞 0.4592 沖北岩 Chongbeiyan 123°35′44〞~123°35′26〞 25°48′01〞~25°48′10〞 0.0183 沖南岩 Chongnanyan 123°37′12〞~123°37′05〞 25°46′31〞~25°46′35〞 0.0048 飛瀨 Feilai 123°33′39〞~123°33′32〞 25°45′23〞~25°45′27〞 0.0008

- ^ "Geographic Location". Diaoyu Dao: The Inherent Territory of China.

Diaoyu Dao and its Affiliated Islands{...}Diaoyu Dao{...}Huangwei Yu{...}Chiwei Yu{...}Beixiao Dao{...}Nanxiao Dao{...}Bei Yu{...}Nan Yu{...}Fei Yu{...}

- ^ 自然环境. 钓鱼岛是中国的固有领土 (in Simplified Chinese).

钓鱼岛及其附属岛屿概况{...}钓鱼岛{...}黄尾屿{...}赤尾屿{...}北小岛{...}南小岛{...}北屿{...}南屿{...}飞屿{...}

- ^ Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI), 魚釣島 (Uotsuri-shima) Archived November 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ 臺灣歷史地圖 增訂版 [Taiwan Historical Maps, Expanded and Revised Edition] (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Taipei: National Museum of Taiwan History. February 2018. p. 156. ISBN 978-986-05-5274-4.

臺海軍事危機地圖1949-1958年{...}釣魚臺{...}地圖繪製:黃清琦

(In the map labeled 臺海軍事危機地圖1949-1958年, the Free area of the Republic of China is colored light green, the PRC (China) is colored red and the Ryukyu Islands are colored pink. The area labeled 釣魚臺 is colored light green. The map was created by Ching-Chi Huang.) - ^ 臺灣閩南語常用詞辭典 [Dictionary of Frequently-Used Taiwan Minnan] (in Chinese and Chinese (Taiwan)). Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

詞目 釣魚台 音讀 Tiò-hî-tâi 釋義 島嶼(附錄-地名-臺灣縣市行政區名)

- ^ GSI, 大正島 (Taishō-tō) Archived November 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ GSI, 久場島 (Kuba-shima) Archived November 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Google Maps, 北小島 (Kita kojima) Archived August 27, 2024, at the Wayback Machine; GSI, 北小島 (Kita kojima) Archived November 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Google Maps, 南小島 (Minami Kojima) Archived August 27, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ GSI, 沖ノ北岩 (Okino Kitaiwa) Archived November 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ GSI, 沖ノ南岩 (Okino Minami-iwa) Archived November 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ GSI, 飛瀬 (Tobise) Archived November 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Ji, Guoxing. (1995). "Maritime Jurisdiction in the Three China Seas", p. 11 Archived August 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine; Sibuet, Jean-Claude et al. "Back arc extension in the Okinawa Trough" Archived June 13, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Journal of Geophysical Research, Vol. 92, Issue B13, pp. 14041-14063.

- ^ a b Ota, Hidetoshi Sakaguchi, Noriaki Ikehara, Sadao Hikida, Tsutomu (June 18, 2008). The Herpetofauna of the Senkaku Group, Ryukyu Archipelago (PDF). University of Hawaii Press. OCLC 652309468. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2021. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Matsumoto, Y., and Tsuji, K. (1973) : Geology of Uotsuri-jima, Kita-kojima and Minami-kojima Archived April 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Bull. Fac. Liberal Arts, Nagasaki Univ. (Nat. Sci.), 14, 43–57 (in Japanese with English abstract).

- ^ "Geology of the Senkaku Islands | Info Library". Review of Island Studies. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Ji, p. 11; excerpt, "In 1893, Empress Dowager Tsu Shih of the Qing Dynasty issued an imperial edict .... China argues that discovery accompanied by some formal act of usage is sufficient to establish sovereignty over the islands." Archived August 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Surveys Between the end of World War II and 1970, Part 1 (1950, 1952, 1953, 1964: University of the Ryukyus)". Review of Island Studies. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ a b "Surveys Between the end of World War II and 1970, Part 2 (1970, 1971: University of the Ryukyus)". Review of Island Studies. Archived from the original on August 27, 2024. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ a b "Surveys following Okinawa's reversion to Japan (1979: Okinawa Development Agency)". Review of Island Studies. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Meiji Era surveys (1900: Kuroiwa and Miyajima)". Review of Island Studies. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2020.

- ^ "Senkaku Islands". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Archived from the original on February 3, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Zoological Society of London, EDGE (Evolutionary Distinct & Globally Endangered) Senkaku mole, 2006; retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ^ "尖閣諸島の自然 – 尖閣諸島の魚たち". Archived from the original on August 27, 2024. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ 夏征农; 陈至立, eds. (September 2009). 辞海:第六版彩图本 [Cihai (Sixth Edition in Color)] (in Chinese). 上海. Shanghai: 上海辞书出版社. Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House. pp. 2193–2194. ISBN 9787532628599.

台湾省{...}包括台湾岛、澎湖列岛和赤尾屿、绿岛、兰屿、彭佳屿、钓鱼岛等岛屿。{...}钓鱼岛 黃尾屿 赤尾屿

- ^ a b 教育部重編國語辭典修訂本 (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Retrieved October 5, 2019.

字詞 【釣魚臺】 注音 ㄉㄧㄠˋ ㄩˊ ㄊㄞˊ 漢語拼音 diào yú tái 釋義{...} 2 群島名。位於臺灣東北,距基隆一百零二海里,為我國領土的一部分。屬宜蘭縣,分為釣魚臺本島、黃尾嶼、赤尾嶼三部分。雖日本主張擁有群島主權,但根據明代陳侃的《使琉球錄》,郭汝霖的《重編使琉球錄》,胡宗憲的《籌海圖編》,以及日本林子平的《三國通覽圖說》等文獻,此島應屬臺灣附屬島嶼。

- ^ a b c d On the sovereignty of Diaoyu Islands Archived February 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (论钓鱼岛主权的归属), Fujian Education Department [verification needed]

- ^ "[1] Archived April 30, 2019, at the Wayback Machine" [verification needed]

- ^ a b c "China's Diaoyu Islands Sovereignty is Undeniable" Archived September 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, People's Daily, 25 May 2003. Retrieved 24 February 2007. [verification needed]

- ^ "Q&A on the Senkaku Islands". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Archived from the original on December 9, 2010. Retrieved October 30, 2014. [verification needed]

- ^ "Koji Taira". Japan Focus. July 2, 2008. Archived from the original on August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2012. [verification needed]

- ^ "Potsdam Declaration (full text)". Archived from the original on January 22, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2014. [verification needed]

- ^ People's Daily, Beijing, China, 31 December 1971, Page 1, "An Declaration of The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China, 1971–12-30" [verification needed]

- ^ Netherlands Institute for the Law of the Sea (NILOS). (2000). International Organizations and the Law of the Sea, p. 108., p. 108, at Google Books

- ^ Ji, pp. 11–12, 19. Archived August 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Ji, p. 11. Archived August 6, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Q&A on the Senkaku Islands". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Archived from the original on December 9, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2019. [verification needed]

- ^ "Japan refuses China demand for apology in boat row". Reuter. September 25, 2010. Archived from the original on September 28, 2010. [verification needed]

- ^ a b "The Basic View on the Sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands". www.mofa.go.jp. Archived from the original on September 30, 2010. Retrieved March 28, 2004. [verification needed]

- ^ a b c "The Basic View on the Sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Archived from the original on September 30, 2010. Retrieved March 28, 2004. [verification needed]

- ^ Satoru Sato, Press Secretary, Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs Letter to the Editor: Clarifying the Senkaku Islands Dispute Archived November 14, 2017, at the Wayback Machine The Wall Street Journal, 21 September 2010 [verification needed]

- ^ Akira Ikegami Special なぜ日中は対立するのか? 映像で見えてきた尖閣問題 (in Japanese). [verification needed]

- ^ 日本的東海政策 — 第四章:釣魚臺政策 (PDF) (in Chinese). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 1, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2013. [verification needed]

- ^ "The Basic View on the Sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Archived from the original on September 30, 2010. Retrieved March 28, 2004. [verification needed]

- ^ Ito, Masami (May 18, 2012). "Jurisdiction over remote Senkakus comes with hot-button dangers". Japan Times. Archived from the original on May 19, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2012. [verification needed]

- ^ "Senkaku Islands". Archived from the original on February 26, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ^ "钓鱼岛_钓鱼岛是中国的固有领 (Diaoyu Islands". Archived from the original on January 29, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ^ "China-Japan Dispute Over Islands Spreads to Cyberspace". The New York Times. January 1, 2015. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved February 23, 2015.

- ^ Page, Jeremy, "Tribunal Rejects Beijing's Claims to South China Sea" Archived February 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Wall Street Journal, July 12, 2016. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ^ Dyer, Geoff, and Tom Mitchell, "South China Sea: Building up trouble" Archived February 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Financial Times, July 15, 2016. With high-resolution aerial image of Fiery Cross Reef. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ^ Obe, Mitsuru, "Japan Presses China on Vessels Sailing Near Disputed Islands" Archived February 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Wall Street Journal, August 24, 2016. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ^ "Ishigaki renames area containing Senkaku Islands, prompting backlash fears". The Japan Times. June 22, 2020. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ "Japan: Ishigaki City Council Votes to Inscribe 'Senkaku' Into Administrative Name of Disputed Islands". The News Lens. June 22, 2020. Archived from the original on August 30, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ "Nation protests Japan's Diaoyutai move". The Taipei Times. June 23, 2020. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ^ "From porn to propaganda: The Truth". ABC Television. May 4, 2014. Archived from the original on August 27, 2024. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ "Japan displays documents to defend claims to disputed isles". The Washington Post. Associated Press. January 25, 2018. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

References

- Belcher, Edward and Arthur Adams. (1848). Narrative of the Voyage of H.M.S. Samarang, During the Years 1843–46: Employed Surveying the Islands of the Eastern Archipelago. London : Reeve, Benham, and Reeve. OCLC 192154 Archived May 7, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- Charney, Jonathan I., David A. Colson, Robert W. Smith. (2005). International Maritime Boundaries, 5 vols. Hotei Publishing: Leiden. ISBN 9780792311874; ISBN 9789041119544; ISBN 9789041103451; ISBN 9789004144613; ISBN 9789004144798; OCLC 23254092

- Findlay, Alexander George. (1889). A Directory for the Navigation of the Indian Archipelago and the Coast of China. London: R. H. Laurie. OCLC 55548028 Archived August 27, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Hagström, Linus. (2005). Japan's China Policy: A Relational Power Analysis. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-34679-5; OCLC 475020946 Archived August 27, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Inoue, Kiyoshi. (1972) Senkaku Letto /Diaoyu Islands The Historical Treatise. Kyoto: Daisan Publisher (出版社: 第三書館) (1996/10)「尖閣」列島―釣魚諸島の史的解明 [単行本] Archived July 17, 2012, at archive.today. ISBN 978-4-8074-9612-9; also hosted in here [2] Archived June 26, 2014, at the Wayback Machine for online reading (set to Shift-JIS character code), with English synopsis here Archived March 9, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. Chinese translation by Ying Hui, Published by Commercial Press Hong Kong (1973) 釣魚列島的歷史和主權問題 / 井上清著 ; 英慧譯 Archived June 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 9622574734.

- Jarrad, Frederick W. (1873). The China Sea Directory, Vol. IV. Comprising the Coasts of Korea, Russian Tartary, the Japan Islands, Gulfs of Tartary and Amúr, and the Sea of Okhotsk. London: Hydrographic Office, Admiralty. OCLC 557221949

- Lai, Yew Meng (2013), Nationalism and Power Politics in Japan's Relations with China: A Neoclassical Realist Interpretation, Routledge, p. 208, ISBN 978-1-136-22977-0

- Lee, Seokwoo, Shelagh Furness and Clive Schofield. (2002). Territorial disputes among Japan, China and Republic of China concerning the Senkaku Islands. Durham: University of Durham, International Boundaries Research Unit (IBRU) Archived October 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. ISBN 978-1-897643-50-1; of China-concerning-the-senkaku-islands/oclc/249501645?referer=di&ht=edition OCLC 249501645 Archived April 20, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- Suganuma, Unryu. (2000). Sovereign Rights and Territorial Space in Sino-Japanese Relations. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2159-3; OCLC 170955369

- Valencia, Mark J. (2001). Maritime Regime Building: Lessons Learned and Their Relevance for Northeast Asia. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 9789041115805; OCLC 174100966

Further reading

- Donaldson, John and Alison Williams. "Understanding Maritime Jurisdictional Disputes: The East China Sea and Beyond", Journal of International Affairs, Vol. 59, No. 1. JSTOR 24358237 .

- Dzurek, Daniel. "The Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands Dispute", International Boundaries Research Unit (IBRU). October 18, 1996.

- Helflin, William B. "Daiyou/Senkaku Islands Dispute: Japan and China, Oceans Apart", 1 Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal, pp. 1–22 (2000).

- O'Hanlon, Michael E. The Senkaku Paradox: Risking Great Power War Over Small Stakes (Brookings Institution, 2019) online review Archived February 17, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- Peterson, Alexander M. "Sino-Japanese Cooperation in the East China Sea: A Lasting Arrangement?" Archived June 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine 42 Cornell International Law Journal, pp. 441–474 (2009).

- Ramos-Mrosovsky, Carlos. "International Law's Unhelpful Role in the Senkaku Islands" Archived February 20, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, 29 University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law, pp. 903–946 (2008).

- Sunohara, Tsuyoshi. Fencing in the Dark: Japan, China, and the Senkakus (Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture, 2020) [3] Archived March 7, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Cabinet Secretariat (Japan), Japan's Response Respecting Law and Order in the International Community / The Senkaku Islands

- Cabinet Secretariat (Japan), Senkaku Islands Research and Commentary Site

- Google Maps: Senkaku Islands

- "Q&A China Japan island row", BBC News Asia-Pacific. September 24, 2010.

- GlobalSecurity.org: "Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands"; References and links

- Inventory of Conflict and Environment (ICE), Diaoyu Islands Dispute

- Hayashi Shihei (1785). 三国通覧図説 (Sangoku Tsuran Zusetsu). Waseda University,

- Senkaku Islands Bibliographical Materials Society Bibliography of primary source material about Senkaku Islands

- "Notes from central Taiwan: Some 'damn foolish thing' in the Senkakus", Taipei Times