Sinyavino_offensive_(1942)

| Sinyavino offensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eastern Front of World War II | |||||||

A typical road for vehicles on the Volkhov Front | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

18th Army Reinforcements: 11th Army |

2nd Shock Army 8th Army Elements of Leningrad Front Total 190,000 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Total 26,000[1][2][a] 5,893 dead |

Total 113,674[3] 28,085 dead and missing 12,000 captured 73,589 wounded and sick | ||||||

The Sinyavino offensive (or third Sinyavino offensive) was an operation planned by the Soviet Union in the summer of 1942 with the aim of breaking the siege of Leningrad, which had begun the previous summer, to establish a reliable supply line to Leningrad. At the same time, German forces were planning Operation Northern Light (German: Nordlicht) to capture the city and link up with Finnish forces. To achieve that heavy reinforcements were arriving from Sevastopol, which the German forces captured in July 1942.[clarification needed] Both sides were unaware of the other's preparations, and this made the battle unfold in an unanticipated manner for both sides.

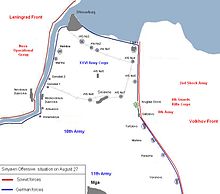

The Soviet offensive began first in two stages. The Leningrad Front began the offensive on 19 August and the Volkhov Front launched the main offensive on 27 August. From 28 August the German side shifted the forces which were building up for their own offensive to gradually halt the Soviet offensive. Initial German counterattacks failed, but the Soviet forces could not advance either. After a ten-day stalemate, the significantly reinforced Germans launched a counterattack against the Soviet forces on 21 September. After five days of heavy fighting, the German forces linked up and cut off the bulge formed by the Soviet offensive.[4] By 10 October the front line returned to the position before this battle; heavy fighting continued until 15 October, as the last pockets of Soviet resistance were destroyed or broke out.

In the end, the Soviet offensive failed, but heavy casualties caused the Germans to order their forces to assume a defensive stance. In November, the German reinforcements and other units were stripped from Army Group North to deal with the major Soviet offensive at Stalingrad and Operation Northern Light was aborted.[5]

Background

The siege of Leningrad started in early autumn 1941. By 8 September 1941 German and Finnish forces had surrounded the city, cutting off all supply routes to Leningrad and its suburbs. However, the original drive on the city failed and the city was subjected to a siege. During the winter 1941–42, the city was partially supplied via the Road of Life over the frozen Lake Ladoga, which allowed the defenders to continue holding out. However, after the siege of Sevastopol ended on 4 July 1942, with the German capture of the city, the German 11th Army was free to be used elsewhere, and Hitler decided that the 11th Army would be used in the assault on Leningrad.[6]

Soviet forces tried to lift the siege, which was causing severe damage to the city and losses in civilian population. The Road of Life was frequently disabled by regular German airstrikes. Several smaller offensives were launched in 1942 in the region, but failed. The last offensive near Lyuban resulted in the encirclement and destruction of most of the Soviet 2nd Shock Army.[7] Nevertheless, the opening of a supply route to Leningrad was so important that preparations for the new operation began almost immediately after the defeat at Lyuban.[8]

Preparations

The area south of Ladoga is heavily forested with many wetlands (notably peat deposits) close to the lake. This terrain hindered the mobility of artillery and vehicles. In addition the forest shielded both sides from visual observation. One of the key locations were the Sinyavino heights, which were approximately 150 metres higher than the surrounding flat terrain. The heights were one of the few dry and clear areas and provided a good spot for observation. The front line changed very little after the blockade was established, allowing the German forces to build a dense defensive network of strong points in the area, interconnected by trenches, protected by extensive obstacles and interlocking artillery and mortar fire.[9]

German plans

The plan to capture Leningrad in summer-autumn 1942 was first outlined in the OKW (German supreme command) directive 41 of 5 April 1942. The directive stressed that the capture of Leningrad and the drive to the Caucasus in the east were the main objectives in the summer campaign on the Eastern Front.[10]

While Army Group Center conducts holding operations, capture Leningrad and link up with the Finns in the north and, on the southern flank, penetrate into the Caucasus region, adhering to the original aim in the march to the east.[11]

During discussions with Hitler on 30 June, the commander of Army Group North, Field Marshal Georg von Küchler, presented him with several operations that would help to carry out this directive. Following these discussions the OKH (German high command) started redeploying heavy artillery from Sevastopol, including the siege artillery batteries Gustav, Dora and Karl, to assist in destroying Soviet defenses and the Kronshtadt fortress. The redeployment was complete by 23 July. On the same day, Fuehrer Directive No. 45 included orders for an operation by Army Group North to capture Leningrad by early September. This operation was named "Feuerzauber" (Fire Magic). The attack was to be carried out by the forces of the 11th Army, which were free to be used elsewhere after the capture of Sevastopol.[12] In addition, the OKH sent the 8th Air Corps to provide air support for land forces. On 30 July the operation was renamed Operation Northern Light (German: Nordlicht).[6]

The formulated operation required three army corps to penetrate the Soviet defenses south of Leningrad. One corps would then cut off Leningrad from the troops to the south and west, while the other two would turn east and destroy the Soviet forces between the Neva River and Lake Ladoga. Then the three corps could capture Leningrad without heavy street fighting.[13]

This would in turn free up the troops involved in the siege for use elsewhere and would make victory on the Eastern Front more likely. Meanwhile, the Germans were also preparing for the Battle of Stalingrad. The 11th Army had a total of 12 divisions under command in the Leningrad area.[6]

Soviet plans

The Soviet Union had tried throughout 1942 to lift the siege. While both the winter and Lyuban offensives operation failed to break the siege of the city, there was now a part of the front where only 16 kilometres (9.9 mi) separated the Leningrad Front in the city and the Volkhov Front.[14] The offensive was to link up the forces of the two fronts and establish a supply route to Leningrad. Because the Leningrad Front was at this time weaker, the Volkhov was to carry out the offensive, while the Leningrad Front would only carry out local attacks and capture bridgeheads across the River Neva. The Volkhov Front's 8th Army was to spearhead the attack, with the 4th Guards Rifle Corps in second and the reforming 2nd Shock Army in third echelon.[15]

Taking into account the difficult and heavily fortified terrain of the upcoming battle, the Soviet troops were, in contrast to their earlier operations, very well equipped. The 8th army was significantly reinforced with artillery and tanks. On average, each first echelon division was reinforced by a tank battalion, a few artillery regiments and one or two batteries of Katyusha rocket launchers. This allowed the Soviets to deploy 60-100 guns and 5-9 tanks per kilometer of frontage of their main offensive. The troops were equipped with large numbers of PPD-40 and PPSh-41 sub-machine guns. Engineering units were attached to individual artillery batteries, increasing the overall mobility of the army.[16][17]

Order of battle

Battle

Neither side was aware that the other was building up forces and planning to launch an offensive in the region. The Germans only realized that the Soviet action was a major offensive in the following days after the start of the attack by the 8th Army on 27 August. This resulted in the 11th Army and the 8th Air Corps being reassigned to deal with a major Soviet offensive and abandon preparations for the offensive on Leningrad.[21] Likewise the Soviet forces were unaware of the redeployment of the 11th Army to Leningrad and only expected to face ten divisions of the 18th Army. The redeployment of forces from the Crimea was not detected. This meant that the Soviet forces were launching an offensive when at a numerical disadvantage even before the battle started.[8]

Soviet offensive, Leningrad Front, 19–26 August

Ultimately the Soviet operation started before the German one, on 19 August, although German sources give later dates.[22] This is because the offensive by the Volkhov Front did not begin until 27 August. The German operation was due to begin on 14 September.[23] The Leningrad Front launched its offensive on 19 August, however due to the limited supplies and manpower, the front was only to capture and expand bridgeheads across the Neva River, that would help it to link up with the Volkhov Front.[16] The German side did not see this as a major offensive, because the Leningrad Front had already mounted several local offensives in July and early August. On 19 August Franz Halder noted in his diary only "local attacks as usual" in the Region. Therefore, no additional defensive measures were taken.[24]

Soviet main offensive, Volkhov Front, 27 August – 9 September

The Volkhov Front offensive started on the morning of 27 August. The hidden buildup of forces allowed the Soviet forces to enjoy a significant superiority on the first day of the offensive in manpower, tanks and artillery and caught the Germans by surprise. The 8th Army had initial success advancing and scattering the first line of German defenses such as the 223rd Infantry Division, advancing 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) on the first day at the location of the main attack. However initial attempts to expand on the flanks failed due to heavy German resistance.[25] The German command reacted by redeploying the 5th Mountain and 28th Light Infantry (Jager) divisions from staging areas for Operation Nordlicht to meet the Soviet offensive. Lead elements from the 170th infantry Division, which had only arrived in Mga, have also joined the offensive. In addition Hitler diverted the 3rd Mountain division, which was being redeployed by sea to Finland, to Estonia instead.[21]

On 29 August the breach in the German defenses was up to 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) deep. To sustain their advance towards Sinyavino, the Soviet forces started committing their second echelon divisions into combat. The German forces were further reinforced by the 12th Panzer and part of the 96th Infantry Divisions. Notably, this day saw the first combat deployment of the Tiger tank, as part of the 502nd Tank Battalion, which on 29 August had four Tigers. The attempt to counterattack with them failed as two of the tanks broke down almost immediately, and the third tank's engine overheated.[20][21]

During this first phase, aerial reinforcements were dispatched to Luftwaffenkommando Ost (Air Command East's) Luftflotte 1 (Air Fleet 1). The Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (High Command of the Air Force) sent several Jagdgeschwader (Fighter Wings) to assist German defences against intense Soviet air attacks. Elements of JG 54 and JG 77 were rushed to provide air superiority operations over the battle front. Despite being opposed by the Soviet 14th Air Army and outnumbered two to one, the Luftwaffe maintained air superiority. Luftflotte 1 destroyed 42 Soviet aircraft in large-scale air battles on the 1 and 2 September and relieved pressure on German ground forces. The German aerial activity was so effective, there was evidence some Soviet airmen's morale had broken down and they were not giving their best in combat. This prompted Joseph Stalin to threaten any pilot refusing to engage with the enemy a court-martial.[19] However Soviet soldiers had to fight “without artillery support. The shells sent for the battalion guns did not fit our 76 mm guns. There were no hand grenades.”[26]

On 5 September Volkhov Front's penetration increased to 9 kilometres (5.6 mi), at the furthest point, thus leaving only 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) to the Neva River. Attempts to capture Sinyavino and the adjacent heights met very heavy resistance and failed. On the flanks, the Soviet forces captured the German strong points at Workers Settlement 8 and Mishino on 3 September, and Voronovo on 7 September. However no more ground was gained after this day in the penetration sector. To try to break the stalemate, the third echelon troops (2nd Strike Army) were used, but German flanking counterattacks forced a halt to the offensive. On 7 September the Volkhov front pulled back two divisions from the 8th Army and replaced them with a fresh division and a tank brigade to achieve further advance.[27]

Stalemate, 10–20 September

The battle turned into a stalemate with neither side gaining any ground despite several attempts to renew the offensive. Between 10 and 19 September there was no major change in the front line. The Soviet side was waiting for reinforcements and air support, hoping to advance the 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) that separated it from the Leningrad Front in the next few weeks, but reinforcements took time.[28]

Having halted the Soviet advance, the German forces now aimed to defeat it. Manstein, who was appointed by Hitler to be in charge of all German forces in the sector, aimed to cut off the bulge formed by the Soviet advance. However, the initial counterattack on 10 September failed with heavy losses, encountering extensive minefields and artillery and mortar fire. Manstein decided to build up forces for a two-pronged attack, while local German counterattacks checked the Soviet attempts to advance.[29]

German counter-offensive, 21 September – 15 October

The main German counter offensive began on 21 September. Six divisions participated in the attack, with 121st Infantry Division attacking from the north, 30th Army Corps' 24th, 132nd and 170th Infantry Divisions from the south and 3rd Mountain and 28th Light Infantry Divisions mounting holding attacks. The 5th Mountain Division suffered heavy casualties in the last ten days and did not play a big role in the counteroffensive.[29]

The counterattacking Germans were facing the same problems as the Soviet forces had faced in the previous month. Advance in difficult terrain overcoming the defensive positions was very slow and casualties were high.[22] Only on 25 September, after five days of very heavy fighting, German forces linked up near Gaitolovo, and part of the Soviet 8th (the 6th Guards Rifle Corps)[19] and 2nd Shock Armies were encircled. After defeating Soviet attempts to relieve or break out of the pocket, it was bombarded by heavy artillery and air strikes. At the same time the 28th Light Infantry and the 12th Panzer divisions defeated the attempts of the Leningrad Front to expand their bridgeheads.[4]

In the heavy fighting from the end of September to 15 October, the German forces reduced the encirclement and recaptured all previously lost strong points, except a small bridgehead held by forces of the Leningrad Front near Moskovkaya Dubrovka.[1]

Aftermath

For the Soviet Union this operation was a costly failure, although with less effect compared to the Soviet defeat near Miasnoy Bor in June and July, where the 2nd Shock Army was almost destroyed and the German forces reported capturing 33,000 prisoners.[30] After only three months the Soviet forces would launch a new offensive, Operation Iskra. That offensive would open a corridor to Leningrad in January 1943.[31]

For the Germans, the effects were bigger. Although the Soviet threat was eliminated and the position of the 18th Army re-established, the 11th Army had suffered serious losses in men, equipment and ammunition. The 18th Army also suffered losses, especially the 223rd Infantry Division, which was opposing the 8th Army on the first day of its offensive.[22] Heavy casualties led to the OKH Operations Order No. 1, which ordered Army Group North to defense during the winter. In November, the German reinforcements and other units were stripped from Army Group North to deal with a major Soviet offensive at Stalingrad and Operation Northern Light was aborted.[5]

Notes

Notes

- ^ Only between 28 August and 30 September

References

- ^ a b Glantz p. 226

- ^ Isayev p. 142, only between 28 August and 30 September

- ^ Glantz (1995), p. 295

- ^ a b Glantz p. 224

- ^ a b Glantz p. 230

- ^ a b c Isayev p. 133

- ^ Isayev p. 134

- ^ a b Isayev p.135

- ^ Glantz pp.216–217

- ^ Isayev p. 132

- ^ Glantz p. 484

- ^ Glantz pp. 212–213

- ^ Glantz p. 213

- ^ Isayev P.135

- ^ Glantz p.217

- ^ a b Isayev p. 135

- ^ Glantz p. 218

- ^ Glantz p. 216

- ^ a b c d Bergström 2003, p. 365.

- ^ a b Isayev p. 139

- ^ a b c d Glantz p. 221

- ^ a b c Haupt W. Army Group North. The Wehrmacht in Russia 1941–1945

- ^ Isayev p. 137

- ^ Glantz p. 217

- ^ Glantz p. 219

- ^ "How the Red Army managed to defend Leningrad during WWII (PHOTOS)". 27 January 2021.

- ^ Glantz p. 222

- ^ Isayev p.140

- ^ a b Glantz p. 223

- ^ Glantz p. 207

- ^ Glantz p. 286

References

- Bergström, Christer (2003). Jagdwaffe: The War in Russia, January–October 1942. Classic Publications. ISBN 1-903223-23-7.

- Glantz, David M. (2002). The Battle for Leningrad 1941-1944. Kansas University Press. ISBN 0-7006-1208-4.

- Glantz and House, David M. and Jonathan M. (1995). When Titans clashed: how the Red Army stopped Hitler. Kansas University Press. ISBN 0-7006-0899-0.

- Haupt, Werner (1997). Army Group North. The Wehrmacht in Russia 1941–1945. Schiffer Military History, Atlegen, PA. ISBN 0-7643-0182-9.

- Krivosheev, Grigoriy. "Россия и СССР в войнах XX века: Потери вооруженных сил: Статистическое исследование" [Russia and the USSR in the wars of the 20th century: Loss of armed forces: Statistical study] (in Russian). Google translation

- Исаев (Isayev), Алексей Валерьевич (2006). Когда внезапности уже не было. История ВОВ, которую мы не знали. (in Russian). М. Яуза, Эксмо. ISBN 5-699-11949-3. Archived from the original on 2009-12-28. Retrieved 2010-01-16.