South West Pacific Area (command)

| South West Pacific Area | |

|---|---|

South West Pacific Area shoulder sleeve insignia | |

| Active | 1942–45 |

| Disbanded | 2 September 1945 |

| Country | |

| Anniversaries | 30 March 1942 |

| Engagements | World War II |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Douglas MacArthur |

South West Pacific Area[note 1] (SWPA) was the name given to the Allied supreme military command in the South West Pacific Theatre of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands in the Pacific War. SWPA included the Philippines, Borneo, the Dutch East Indies (excluding Sumatra), East Timor, Australia, the Territories of Papua and New Guinea, and the western part of the Solomon Islands. It primarily consisted of United States and Australian forces, although Dutch, Filipino, British, and other Allied forces also served in the SWPA.

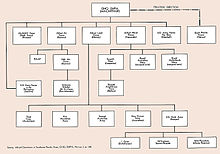

General Douglas MacArthur was appointed as the Supreme Commander, Southwest Pacific Area, on its creation on 18 April 1942. He created five subordinate commands: Allied Land Forces, Allied Air Forces, Allied Naval Forces, United States Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA), and the United States Army Forces in the Philippines. The last command disappeared when Corregidor surrendered on 6 May 1942, while USAFIA became the United States Army Services of Supply, Southwest Pacific Area (USASOS SWPA). In 1943 United States Army Forces in the Far East was reformed and assumed responsibility for administration, leaving USASOS as a purely logistical agency. Both were swept away in a reorganisation in 1945. The other three commands, Allied Land Forces, Allied Air Forces and Allied Naval Forces, remained until SWPA was abolished on 2 September 1945.

Origins

The forerunner of the South West Pacific Area was the short-lived American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDA). In December 1941 and January 1942 ABDA was referred to as the South West Pacific Area.[1] The rapid Japanese advance through the Dutch East Indies effectively divided the ABDA area in two and, in late February 1942, ABDA was dissolved at the recommendation of its commander, General Sir Archibald Wavell, who—as Commander-in-Chief in India—retained responsibility for Allied operations in Burma and Sumatra.[2]

Another command, established under emergency conditions when a convoy intended for supply of the Philippines, known as the Pensacola Convoy, was rerouted to Brisbane due to the attack on Pearl Harbor. Brigadier General Julian F. Barnes was ordered to assume command of all troops in the convoy on 12 December 1941 concurrent with their designation as Task Force—South Pacific, and place himself under the command of MacArthur.[3][4] The next day, by radiogram, the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, General George C. Marshall, ordered Barnes to assume command as Commander, US Troops in Australia and take charge of all troops and supplies.[4] On 22 December 1941, with the convoy's arrival in Brisbane, the command was designated as United States Forces in Australia (USFIA). It was renamed U.S. Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA) on 5 January 1942.[4] Its mission was to create a base in Australia for the support of the forces still in the Philippines.[5][4][6]

The staff, known as the "Remember Pearl Harbor" (RPH) group, selected by the War Department for USAFIA arrived Melbourne 1 February 1942 aboard SS President Coolidge and SS Mariposa in the first large convoy bearing personnel, supplies and munitions intended for transhipment to Java and Philippines as well as Australia.[7] For a brief time, due to the increased isolation of the Philippines and before the fall of Java, USAFIA was withdrawn from MacArthur's command and placed under the ABDA with continued direction to support both Java and the Philippines.[8][9]

What would replace ADBA was the subject of discussions between the Australian and New Zealand chiefs of staff that were held in Melbourne between 26 February and 1 March 1942. They proposed creating a new theatre of war encompassing Australia and New Zealand, under the command of Wavell's former deputy, Lieutenant General George Brett, who had assumed command of the US Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA) on 25 February.[10]

The President of the United States, Franklin Roosevelt, and the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Winston Churchill, discussed the matter of command arrangements in the Pacific in Washington, D.C., on 9 March. Roosevelt proposed that the world would be divided into British and American areas of responsibility, with the United States having responsibility for the Pacific, where there would be an American supreme commander responsible to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Churchill responded favourably to the proposal, and the governments of Australia and New Zealand were then consulted. They endorsed the idea of an American supreme commander, but wanted to have some input into matters of strategy.[10]

This resulted in the creation of the Pacific War Council, which met for the first time in London on 10 February 1942. Churchill, Clement Attlee (Deputy Prime Minister) and Anthony Eden (Foreign Secretary) represented the United Kingdom, and Earle Page represented Australia, along with representatives from the Netherlands, New Zealand, India and China. Page was replaced as the Australian representative by Stanley Bruce in June 1942. A parallel Pacific War Council was created in Washington, D.C., that first met on 1 April 1942. It was chaired by Roosevelt, with Richard Casey and later Owen Dixon representing Australia, and Prime Minister Mackenzie King representing Canada. The Pacific War Council never became an effective body, and had no influence on strategy, but did allow the Dominions to put their concerns before the President.[11][12]

Formation

The obvious choice for a supreme commander in the Pacific was General Douglas MacArthur. He had been ordered to leave the Philippines for Australia to take command of a reconstituted ABDA area on 22 February 1942, and had therefore been promised the command even before there were discussions on what it should be. MacArthur had solid support from the President, the Army and the American people, but not the Navy. The Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, Admiral Ernest King, saw the Pacific lines of communication primarily as a naval responsibility and would not yield command to an Army officer and proposed a division placing all of the Solomons within the Australian area, but excluding the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, and New Zealand.[13] While the Army planners, led by Brigadier General Dwight Eisenhower, were willing to compromise on a divided command, they objected to placing Australia and New Zealand in separate theatres. The Joint Chiefs of Staff discussed the matter between 9 and 16 March, the result of which was a decision to adopt the Navy's plan, with only minor amendments.[14]

While this was still going on General Marshall, had contacted Brett and asked him to get the Australian government to nominate MacArthur, whose arrival in Australia was now imminent, as its choice for supreme commander. This was done on 17 March when MacArthur arrived at Batchelor, Northern Territory. On 24 March 1942, the Combined Chiefs of Staff issued a directive formally designating the Pacific theatre an area of American strategic responsibility. On 30 March, the Joint Chiefs of Staff divided the Pacific theatre into three areas: the Pacific Ocean Areas (POA), under Admiral Chester Nimitz; the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA), under MacArthur; and the Southeast Pacific Area, which never became an active theatre. The former Anzac Area was divided between SWPA and the POA.[15]

An annex defined SWPA's boundaries:

From Cape Kami in the Luichow Peninsula around the coast of the Tonkin Gulf, Indo-China, Thailand, and Malaya to Singapore: from Singapore south to the north coast of Sumatra, thence round the east coast of Sumatra (leaving the Sunda Strait to the eastward of the line) to a point on the coast of Sumatra at Longitude 104° East, thence south to Latitude 08° South, thence southeasterly towards Onslow, Australia, and on reaching Longitude 110° East, due south along that meridian. ... The north and east boundaries... : From Cape Kami...south to Latitude 20° North; thence east to Longitude 130° East; thence south to the Equator; thence east to Longitude 165° East; south to Latitude 10° South; southwesterly to Latitude 17° South, Longitude 160° East; thence south.[16]

On 17 April 1942 the Prime Minister of Australia, John Curtin, directed all Australian defence forces personnel to treat orders from MacArthur "as emanating from the Commonwealth Government".[17][18] The Army's workshops and fixed fortifications, and the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF)'s logistical and training infrastructure, were not placed under SWPA.[18] Having placed its troops at MacArthur's disposal, the Australian government was adamant that it should be consulted on any alteration to the boundaries or command arrangements in SWPA.[19] The government was particularly concerned that the Supreme Commander should not move troops outside Australia or Australian territory without its consent,[20] as there were legal restrictions on where the Australian Militia could serve.[21] The matter of changes in command first came up when Brett was replaced as Commander of Allied Air Forces by the Joint Chiefs of Staff. MacArthur and Curtin agreed that there would be no change to General Sir Thomas Blamey's status (as Australian Army Commander-in-Chief), and that the government would be consulted about any other proposed changes. When Vice Admiral Herbert F. Leary was replaced a few months later, Curtin was consulted, and concurred with the change.[22]

General Headquarters

MacArthur became the Supreme Commander Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) on 18 April 1942, although he preferred to use the more conventional title of Commander in Chief.[17] MacArthur's first General Order created five subordinate commands: Allied Land Forces, Allied Air Forces, Allied Naval Forces, United States Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA), and the United States Army Forces in the Philippines.[17] The last command had a short life. Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainwright's United States Army Forces in the Philippines disintegrated over the following three weeks, and disappeared entirely when Wainwright surrendered on Corregidor on 6 May.[23]

MacArthur announced the composition of his staff, known as General Headquarters (GHQ) on 19 April. Major General Richard K. Sutherland became Chief of Staff; Brigadier General Richard J. Marshall, Deputy Chief of Staff; Colonel Charles P. Stivers, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-1; Colonel Charles A. Willoughby, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2; Brigadier General Stephen J. Chamberlin, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3; Colonel Lester J. Whitlock, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4; Brigadier General Spencer B. Akin, Signal Officer; Brigadier General Hugh J. Casey, Engineer Officer; Brigadier General William F. Marquat, Antiaircraft Officer; Colonel Burdette M. Fitch, Adjutant General; and Colonel LeGrande A. Diller, Public Relations Officer.[17]

Although Marshall had recommended that MacArthur appoint as many Australian and Dutch officers to senior positions as possible, most of his staff was made up of US Army officers who had served under him in the Philippines. The rest, including Whitlock, Fitch and Chamberlain, had been on the staff of USAFIA. MacArthur reported to Marshall that there were no qualified Dutch officers in Australia, and that the Australian Army had a critical shortage of staff officers, which he did not wish to exacerbate. Nevertheless, several Dutch and Australian army officers, as well as some American naval officers, served in junior positions on the staff.[17][24]

In July, MacArthur moved his GHQ north, from Melbourne to Brisbane, where it was located in the AMP Building. The original intention had been to move to Townsville, but this was found to be impractical, as Townsville lacked the communications facilities that GHQ required.[25] The Allied Air Forces and Allied Naval Forces headquarters were co-located with GHQ in the AMP building. The Advanced Headquarters of Allied Land Forces opened at St Lucia, about 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) away.[24] The Advanced GHQ subsequently moved to Hollandia in September 1944,[26] Leyte in October 1944,[27] and Manila in May 1945.[28]

There was a major reorganisation in April 1945 for the planned invasion of Japan. All Army forces in the Pacific were placed under MacArthur's command, including those in Nimitz's Pacific Ocean Areas. A new command was formed, Army Forces Pacific (AFPAC), with GHQ operating as the headquarters of both AFPAC and SWPA. Units in POA remained under Nimitz's operational control, and the first major formation, the Tenth United States Army, did not pass to AFPAC control until 31 July 1945.[29] SWPA, together with the Allied Air Forces, Allied Naval Forces and Allied Land Forces, was abolished on 2 September 1945, but GHQ remained as GHQ AFPAC.[30]

Allied Land Forces

The Australian Army's Commander in Chief, General Sir Thomas Blamey, was appointed Commander, Allied Land Forces, SWPA. His headquarters was the existing General Headquarters (Australia), and became known as LHQ. An Australian commander was chosen as most of the land forces were Australian. In April 1942, there were 38,000 American ground troops in SWPA and 369,000 Australian. LHQ controlled five major commands: Lieutenant General Sir John Lavarack's First Army, based in Queensland; Lieutenant General Sir Iven Mackay's Second Army in Victoria; Lieutenant General Gordon Bennett's III Corps in Western Australia; the Northern Territory Force under Major General Edmund Herring; and New Guinea Force under Major General Basil Morris. Between them they controlled ten Australian and two American divisions.[31] In August 1944, the Australian Army had a strength of 463,000 men and women, and there were 173,000 US Army ground personnel in SWPA.[32] By late 1944, there were eighteen American divisions in SWPA,[33] while the Australian Army had just seven.[34]

When GHQ moved up to Brisbane, LHQ remained behind in Melbourne, but Blamey formed an Advanced LHQ under his Deputy Chief of the General Staff (DCGS), Major General George Alan Vasey, which moved to nearby St Lucia.[35][36] Major General Frank Berryman replaced Vasey as DCGS in September 1942, and remained in the post until January 1944. He resumed the post in July 1944 and remained until December 1945. When the main body of GHQ moved to Hollandia, Advanced LHQ followed, opening there on 15 December, but when the main GHQ moved to Leyte in February 1945, Advanced LHQ remained behind. A Forward Echelon LHQ was formed under Berryman that remained co-located with the main body of GHQ, while the main body of LHQ remained at Hollandia until it moved to Morotai for the operations in Borneo in April 1945.[37]

In practice, MacArthur controlled land operations through "task forces".[38] These reported directly to GHQ, and their commanders could control all Allied land, air, naval and service forces in their area if a Japanese land attack was imminent.[39] The most important of these was New Guinea Force, which was formed in 1942 and was commanded personally by Blamey in September 1942,[40] and again in September 1943.[41] In February 1943, Lieutenant General Walter Krueger's Sixth Army arrived in SWPA, and its headquarters became that of Alamo Force. Alamo Force reported directly to MacArthur, and as a result Blamey did not command of the majority of American land forces in the theatre after that time, although his post was not abolished.[42][41]

In March 1944, MacArthur met with Curtin and detailed his plans for the Western New Guinea campaign, explaining that he would assume direct command of land forces when he reached the Philippines, and suggesting that Blamey could either go with him as an army commander, or remain in Australia as Commander in Chief.[43] The new organisation went into effect in September 1944, with Lieutenant General Walter Krueger's Sixth US Army, Lieutenant General Robert Eichelberger's Eighth United States Army, Lieutenant General Vernon Sturdee's First Australian Army, Lieutenant General Leslie Morshead's I Australian Corps and Major General Oscar Griswold's XIV Corps reporting directly to GHQ.[44] Allied Land Forces remained as an important administrative and logistical command,[37] until it was abolished, along with SWPA, on 2 September 1945.[30]

Allied Air Forces

The April 1942 reorganisation that created the Allied Land Forces and Allied Naval Forces also created the Allied Air Forces under Brett.[17] Unlike MacArthur, Brett created a completely integrated headquarters,[45] with a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) officer, Air Vice Marshal William Bostock, as his chief of staff. Each United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) staff officer was paired with a RAAF officer, with the senior staff posts divided evenly between them. A majority of command positions were held by Australians.[46] To make up shortages of USAAF aircrew, RAAF aircrew were assigned to USAAF air groups, serving in every role except aircraft commander.[47]

In May 1942, the Australian government appointed Air Vice Marshal George Jones as Chief of the Air Staff. He became responsible for matters other than operations, such as administration and training.[46] It soon became clear that Jones and Bostock could not get along together, but Kenney preferred to have Bostock in operational command, and although he regarded the antipathy between Jones and Bostock as a nuisance, was happy to leave arrangements the way they were.[48]

One of MacArthur's first orders to Brett was for a bombing mission to the Philippines, an order delivered personally by Sutherland. When Brett protested, Sutherland informed him that MacArthur wanted the mission carried out. The mission was flown by Brigadier General Ralph Royce, but MacArthur personally wrote a reprimand to Brett. Henceforth, communications with Sutherland were handled by Bostock. Further disagreements between MacArthur and Brett followed.[49] Meanwhile, in Washington, General George Marshall and the Chief of Army Air Forces, Lieutenant General Henry Arnold, had become alarmed at Brett's integration of the USAAF and RAAF, and disturbed by his inability to work with MacArthur.[50] On 6 July 1942 Marshall radioed MacArthur to offer him Major General George Kenney or Brigadier General Jimmy Doolittle as a replacement for Brett; MacArthur selected Kenney.[51]

Kenney sent home Major General Royce, Brigadier Generals Edwin S. Perrin, Albert Sneed and Martin Scanlon,[52] and about forty colonels.[53] In Australia he found two talented, recently arrived brigadier generals, Ennis Whitehead and Kenneth Walker.[54] Kenney reorganised his command in August, appointing Whitehead as commander of the V Fighter Command and Walker as commander of the V Bomber Command.[55] Allied Air Forces was composed of both USAAF and RAAF personnel, and Kenney moved to separate them. Brigadier General Donald Wilson arrived in September and replaced Air Vice Marshal Bostock as Kenney's chief of staff, while Bostock took over the newly created RAAF Command.[56] Walker was shot down over Rabaul in January 1943.[57] His successor, Brigadier General Howard Ramey, disappeared in March 1943.[58]

Kenney deviated from the normal structure of an air force by creating the Advanced Echelon (ADVON) under Whitehead. The new headquarters had the authority to alter the assignments of aircraft in the forward area, where fast-changing weather and enemy action could invalidate orders drawn up in Australia.[59] He created the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Air Task Forces to control air operations in a forward area for a specific mission, another departure from doctrine. While Kenney was enthusiastic about this innovation, Washington did not like it and, over Kenney's objections, converted the three air task forces into the 308th, 309th and 310th Bombardment Wings. In June 1944, Major General St. Clair Streett's Thirteenth Air Force was added to the Allied Air Forces. Kenney created the Far East Air Forces (FEAF) from his Fifth Air Force headquarters, while ADVON became the Fifth Air Force under Whitehead.[60] The RAAF formed the Australian First Tactical Air Force under Air Commodore Harry Cobby in October 1944,[61] and when MacArthur became commander of all Army forces in the Pacific, the Seventh Air Force was added as well.[62] Major General Paul Wurtsmith replaced Streett in March 1945,[63] and Air Commodore Frederick Scherger replaced Cobby in May.[61] Allied Air Forces was abolished on 2 September 1945.[30]

Allied Naval Forces

Vice Admiral Leary was appointed Commander, Allied Naval Forces, in April 1942.[17] On 7 February 1942, he had become commander of the Anzac Area to the east of Australia extending to include Fiji with headquarters in Melbourne.[64] That command included a naval element, some air forces but without responsibility for land defense.[65] He was answerable directly to Admiral King. The most important force under his command was Rear Admiral John Gregory Crace's Anzac Squadron.[66][67] When SWPA and the Allied Naval Forces were formed in April 1942, Leary also became Commander, Southwest Pacific Force (COMSOUWESPAC), while Crace's Anzac Squadron became Task Force 44.[68] In June, Crace was succeeded by another Royal Navy officer, Rear Admiral Victor Crutchley.[69] The former Anzac Area was divided so that the Australian coastal waters were with SWPA and the sea and air lines of communication from Hawaii and North America fell in the Pacific Ocean Areas (POA) with a special provision for the South Pacific Area having a designated sub commander under Admiral Chester Nimitz.[70]

With the agreement of the Australian government,[22] Leary was succeeded as Commander, Southwest Pacific Force, and Commander, Allied Naval Forces, by Vice Admiral Arthur S. Carpender on 11 September 1942.[71] Like his predecessor, he reported to King in the former role, and MacArthur in the latter. Also like Leary, Carpender was not the most senior naval officer in the theatre, as the Royal Australian Navy Chief of the Naval Staff (CNS), Admiral Sir Guy Royle, and the Royal Netherlands Navy′s Vice Admiral Conrad Helfrich were both senior to him.[72] However, Royle agreed to serve under Carpenter as Commander, South West Pacific Sea Frontier, which was formed on 16 March 1943.[73]

The Southwest Pacific Force was renamed the Seventh Fleet on 15 March 1943, and its task forces were renumbered to match, so Task Force 44 became Task Force 74.[73] Another important component was Task Force 76, the Amphibious Force, Southwest Pacific, which had been formed under Rear Admiral Daniel Barbey on 8 January 1943. It became the VII Amphibious Force later in the year. A training centre, HMAS Assault was established at Port Stephens, New South Wales, and another at Toorbul Point, Queensland. The VII Amphibious Forces initially consisted of the Australian Landing Ships, Infantry HMAS Manoora, Westralia and Kanimbla and the American attack transport USS Henry T. Allen, but gradually grew in size as more landing craft and landing ships arrived.[74][73]

MacArthur was annoyed at the way that Royle, a Royal Navy officer, communicated directly with the Admiralty; he was also aware that Royle had been critical of SWPA's command arrangements, and of some of his decisions. MacArthur proposed that an Australian officer, Captain John Collins, replace Royle as CNS, an appointment that Carpender also supported.[75] Over the Admiralty's objections, Curtin appointed Collins to replace Crutchley as Commander, Task Force 44, in June 1944, at the rank of commodore, with the intention that Collins would replace Royle when his term expired.[76] This did not occur, because Collins was seriously wounded in Leyte Gulf on 21 October 1944.[77]

MacArthur did not get along with Carpender, and twice asked for him to be replaced, only to be embarrassed in November 1943 when King replaced Carpender with Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid without informing MacArthur or seeking the approval of the Australian government. However, a face-saving formula was agreed upon.[78] For the invasion of Leyte, the Seventh Fleet was massively reinforced by ships from the Pacific Fleet. Cover was provided by Admiral William F. Halsey's Third Fleet, which remained under Nimitz.[79] At the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the divided command brought the Allies to the brink of disaster when misunderstandings arose between Kinkaid and Halsey.[80] Allied Naval Forces was abolished, along with SWPA, on 2 September 1945.[30]

U.S. Army Services of Supply

Under U.S. Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA) a series of bases had gradually been built in Australia, initially to support the US forces in the Philippines. Seven base sections were established in Australia to operate under USAFIA: Base Section 1 at Birdum, Northern Territory; Base Section 2 in Townsville; Base Section 3 in Brisbane; Base Section 4 in Melbourne; Base Section 5 in Adelaide; Base Section 6 in Perth; and Base Section 7 in Sydney.[81] On 20 July USAFIA became the United States Army Services of Supply, Southwest Pacific Area (USASOS SWPA), under the command of Brigadier General Richard J. Marshall, and Barnes returned to the United States.[82][25]

When Lieutenant General Krueger's Sixth United States Army headquarters arrived in Australia in February 1943, the administrative functions were taken from USASOS and given to a new headquarters, United States Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), under MacArthur's command. This had the same name as MacArthur's old headquarters in the Philippines, but its function was different. This left USASOS with logistical responsibilities only.[82] The new arrangement was awkward, and required considerable adjustment before it functioned properly. In September 1943, Marshall was replaced by Brigadier General James L. Frink.[83]

The New Guinea Advanced Base was formed in Port Moresby in August 1942, and sub bases were created at Milne Bay and Oro Bay. These became Advanced Sub Base A and Advanced Sub Base B respectively in April 1943. Advanced Sub Base C was created on Goodenough Island in April 1943, but was discontinued when the island was handed over to Sixth Army control in July. Meanwhile, Advanced Sub Base D was formed at Port Moresby in May. The sub bases became bases in August 1943. Advanced Base E was formed at Lae and Advanced Base F at Finschhafen in November 1943,[84] followed by Bases G and H at Hollandia and Biak respectively.[85]

With a worldwide shipping crisis[86] and SWPA being at the end of a very long supply line, as well as being a region without well developed transportation nets, regional logistics were almost entirely dependent on water transport.[87][88] No one fleet composed the assets available to the Commander in Chief, SWPA as the U. S. Navy, Royal Navy, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Army, Netherlands East Indies Navy were under his operational command while being maintained under their respective organizations.[89] Those assets were inadequate resulting in the creation of a large Army fleet unique to SWPA, the Permanent Local Fleet, under first USFIA, later USASOS and finally Army Forces, Western Pacific (AFWESPAC), starting with the retention of the USAT Meigs, Admiral Halstead and Coast Farmer from the convoy diverted to Brisbane in December 1941.[90]

That core was augmented by vessels fleeing the Japanese advance, particularly twenty-one Dutch vessels later known as the "KPM vessels" after the Dutch shipping line's name, Koninklijke Paketvaart-Maatschappij.[91] As of 28 April 1942 the Army fleet had grown to twenty-eight ships and by 24 January 1945 that fleet of large ships exceeded ninety with a peak of ninety-eight by 1 August 1945.[92] That number did not count a much larger fleet of small vessels, ranging from landing craft, barges and other floating equipment to seagoing vessels under 1,000 tons, including the Small Ships Section of requisitioned and locally constructed (2,712 craft) vessels crewed largely by Australian civilian employees, 1,719 as of June 1945,[93] of the U.S. Army, and many such vessels and floating equipment delivered from the United States.[94] The permanent fleet of SWPA almost had as many vessels as the Army's general fleet during some periods, though those vessels were often small, obsolete, in poor condition and under unorthodox management in comparison.[95]

As the Allied forces advanced, new bases were formed, and the old ones in Australia were closed. Base Sections 5 and 6 were closed in January 1943, and Base Section 4 in June 1944. The remaining four became bases, and a Base Section was formed in Brisbane to control them. Bases 1 and 3 were closed in December 1944, leaving only Bases 2 and 7.[85] These were deactivated in June 1945 and their functions absorbed by the Australia Base Section, as the Base Section had been renamed in February 1945. In New Guinea, Base D was closed in July 1945, and Bases A, B and E in September, leaving Bases F, G and H.[96] Meanwhile, a series of bases were opened in the Philippines: Base K on Leyte, Base M on Luzon, Base R at Batangas, Base S on Cebu and base X at Manila. These came under the Luzon Base Section, which was redesignated the Philippine on 1 April 1945. [97] On 7 June 1945, USASOS became AFWESPAC, under the command of Lieutenant General Wilhelm D. Styer, and it absorbed USAFFE.[29]

Intelligence

In April 1942, Brigadier General Spencer Akin and his Australian counterpart at LHQ, Major General Colin Simpson, agreed to pool their resources and establish a combined intelligence organisation, known as the Central Bureau. The Australian, British, and US Armies, as well as the RAAF and the RAN all supplied personnel for this formation, which worked on codebreaking and decrypting Japanese message traffic. This Magic and Ultra intelligence was vitally important to operations in SWPA.[98]

To handle other forms of intelligence, Blamey and MacArthur created the Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB). This included the Services Reconnaissance Department with its Z Special Unit that carried out special operations like Operation Jaywick; Secret Intelligence Australia; the Coastwatchers, who watched for Japanese aircraft and ships from observation posts behind Japanese lines; and the propaganda specialists of the Far Eastern Liaison Office (FELO). Two other important combined organisations, not part of AIB, were the Allied Translator and Interpreter Section (ATIS), which translated Japanese documents, and the Allied Geographical Section, which prepared maps and charts, and drafted appreciations of the terrain.[99]

Since quality tended to be more important than quantity in intelligence, this proved to be a fruitful field in which the minor Allies, Australia and the Netherlands, could play a key part. Good intelligence enabled the Allied forces to minimise the risk of failures and maximise the chances of success. Moreover, the organisation built up in Australia proved to be useful after the war as well. David Horner later wrote that "it may prove that present day intelligence cooperation has proved to be the most lasting and important legacy of Australia's experience of coalition warfare in the Second World War."[100]

Legacy

The Allied command structure in the South West Pacific Area faced the challenges of coalition warfare in several ways, with varying degrees of success. The benefits of the wartime alliances proved to be substantial, but required constant effort to maintain. For Australia and New Zealand, coalition warfare became the norm, and the experience in SWPA proved to be a formative and informative one, with many political and military lessons. Over the following decades, Australian, New Zealand and American forces would fight together again, in the Korean War, Vietnam War and the War on Terror.[101]

Footnotes

- ^ "Southwest Pacific Area in American English became "South West Pacific Area" in Australian English. Due to the activities of Australian typists, the latter became more widely used.

Notes

- ^ Hasluck 1970, p. 49.

- ^ Morton 1962, pp. 240–242.

- ^ Morton 1993, pp. 145–148.

- ^ a b c d Masterson 1949, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Morton 1962, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Casey 1953, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Mayo 1991, pp. 40.

- ^ Leighton & Coakley 1995, p. 170.

- ^ Mayo 1991, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Morton 1962, pp. 242–245.

- ^ Gwyer & Butler 1964, p. 437.

- ^ Hasluck 1970, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Morton 1962, p. 246.

- ^ Morton 1962, pp. 244–246.

- ^ Morton 1962, pp. 244–249.

- ^ Hayes 1982, p. 765.

- ^ a b c d e f g Milner 1957, p. 22.

- ^ a b Hasluck 1970, p. 113.

- ^ Horner 1982, p. 309.

- ^ Hasluck 1970, p. 112.

- ^ Hasluck 1970, p. 60.

- ^ a b Hasluck 1970, p. 115.

- ^ Morton 1962, pp. 264–268.

- ^ a b Horner 1982, pp. 206–207.

- ^ a b Milner 1957, p. 48.

- ^ Horner 1982, p. 342.

- ^ Horner 1982, p. 348.

- ^ James 1975, p. 667.

- ^ a b Casey 1953, p. 174.

- ^ a b c d Casey 1953, p. 311.

- ^ McCarthy 1959, pp. 24–26.

- ^ Dexter 1961, p. 227.

- ^ Long 1963, p. 19.

- ^ Long 1963, p. 31.

- ^ McCarthy 1959, p. 174.

- ^ Long 1963, p. 593.

- ^ a b Long 1963, pp. 24, 47.

- ^ Long 1963, pp. 46–47.

- ^ McCarthy 1959, pp. 74, 159.

- ^ McCarthy 1959, p. 236.

- ^ a b Dexter 1961, p. 221.

- ^ Long 1963, pp. 594–595.

- ^ Horner 1982, pp. 309–310.

- ^ GHQ Operations Instructions No. 67, 9 September 1944, Australian War Memorial: Blamey Papers, 3DRL 6643 3/102

- ^ Horner 1982, p. 207.

- ^ a b Horner 1982, pp. 350–353.

- ^ McAulay 1991, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Griffith 1998, p. 63.

- ^ Rogers 1990, pp. 276–277.

- ^ Horner 1982, pp. 207, 353.

- ^ Wolk 1987, p. 165.

- ^ Wolk 1988, p. 92.

- ^ Wolk 1987, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Kenney 1949, p. 11.

- ^ Barr 1997, p. 20.

- ^ Kenney 1949, p. 100.

- ^ Kenney 1949, p. 176.

- ^ Kenney 1949, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Rodman 2005, p. 77.

- ^ Griffith 1998, pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b Stephens 2001, pp. 168–170.

- ^ Kenney 1949, pp. 537–538.

- ^ Kenney 1949, p. 519.

- ^ Gill 1957, p. 520.

- ^ Morton 1962, p. 201.

- ^ Gill 1957, pp. 520–521.

- ^ Gill 1968, p. 4.

- ^ Gill 1968, p. 34.

- ^ Gill 1968, p. 113.

- ^ Morton 1962, pp. 245–246.

- ^ Gill 1968, p. 236.

- ^ Wheeler 1994, pp. 346–349.

- ^ a b c Gill 1968, p. 277.

- ^ Morison 1950, p. 131.

- ^ Horner 1982, pp. 364–366.

- ^ Gill 1968, pp. 380, 441.

- ^ Gill 1968, p. 512.

- ^ Wheeler 1994, pp. 343–344.

- ^ Gill 1968, pp. 494–496.

- ^ Wheeler 1994, pp. 404–406.

- ^ Casey 1953, pp. 250–251.

- ^ a b Casey 1953, p. 37.

- ^ Bykovsky & Larson 1957, p. 428.

- ^ Casey 1953, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b Casey 1953, p. 120.

- ^ Leighton & Coakley 1995, pp. 195–196.

- ^ Masterson 1949, pp. vi–ix, 242.

- ^ Leighton & Coakley 1995, pp. 390–392.

- ^ Masterson 1949, pp. 317–318.

- ^ Masterson 1949, pp. 319–318.

- ^ Masterson 1949, pp. 321–324.

- ^ Masterson 1949, p. 339.

- ^ Masterson 1949, pp. Appendix 49, p. 1.

- ^ Masterson 1949, pp. 368–380.

- ^ Grover 1987, p. 5.

- ^ Casey 1953, p. 184.

- ^ Casey 1953, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Horner 1982, pp. 226–230.

- ^ Horner 1982, pp. 237–242.

- ^ Horner 1982, p. 246.

- ^ Horner 2005, pp. 123–124.

References

- Barr, James A. (1997). Airpower Employment of the Fifth Air Force in the World War II Southwest Pacific Theater (M.A. thesis). Maxwell Air Force Base: Air University. Archived from the original on April 8, 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- Bykovsky, Joseph; Larson, Harold (1957). The Transportation Corps: Operations Overseas (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army. OCLC 1358605. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- Casey, Hugh J., ed. (1953). Organization, Troops and Training. Engineers of the Southwest Pacific. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. OCLC 16114940.

- Dexter, David (1961). The New Guinea Offensives. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

- Gill, G. Hermon (1957). Royal Australian Navy 1939–1942. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

- Gill, G. Hermon (1968). Royal Australian Navy 1942–1945. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

- Griffith, Thomas E. Jr. (1998). MacArthur's Airman: General George C. Kenney and the War in the Southwest Pacific. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0909-1. OCLC 38885310.

- Grover, David H., ed. (1987). U.S. Army Ships and Watercraft of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland USA: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-766-6. LCCN 87-15514.

- Gwyer, J M. A.; Butler, J R. M. (1964). Grand Strategy, Vol.3. History of the Second World War. H.M.S.O. OCLC 230089734.

- Hasluck, Paul (1970). The Government and the People 1942–1945. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 33346943.

- Hayes, Grace P. (1982). The History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in World War II: The War against Japan. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-269-9. OCLC 7795125.

- Horner, David (1982). High Command: Australia and Allied Strategy 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 0-86861-076-3. OCLC 9464416.

- Horner, David (2005). "Australia and Coalition Warfare in the Second World War". In Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey (eds.). Entangling Alliances: Coalition Warfare in the Twentieth Century. Canberra: Australian Military History Publications. pp. 105–124. ISBN 1-876439-71-8. OCLC 225414839.

- James, D. Clayton (1975). Volume 2, 1941–1945. The Years of MacArthur. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-20446-1. OCLC 12591897.

- Kenney, George C. (1949). General Kenney Reports: A Personal History of the Pacific War. New York City: Duell, Sloan and Pearce. ISBN 0-16-061372-8. OCLC 37302833.

- Leighton, Richard M.; Coakley, Robert W. (1995). Global Logistics And Strategy 1940–1943 (PDF). United States Army In World War II—The War Department. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. LCCN 55-60001. OCLC 63151391. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- Long, Gavin (1963). The Final Campaigns. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

- Masterson, Dr. James R. (1949). U. S. Army Transportation In The Southwest Pacific Area 1941–1947. Washington: Transportation Unit, Historical Division, Special Staff, U. S. Army. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- Mayo, Lida (1991). The Ordnance Department: On Beachhead And Battlefront. United States Army In World War II — The Technical Services. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 79014631. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- McCarthy, Dudley (1959). South-West Pacific Area – First Year. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

- McAulay, Lex (1991). Battle of the Bismarck Sea. New York: St Martins Press. ISBN 0-312-05820-9. OCLC 23082610.

- Milner, Samuel (1957). Victory in Papua (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. LCCN 56-60004. OCLC 220484034. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1950). Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier: 22 July 1942 – 1 May 1944. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. OCLC 10310299.

- Morton, Louis (1993). The Fall Of The Philippines. United States Army In World War II—The War in the Pacific. Washington: Center Of Military History, United States Army. LCCN 53-63678. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- Morton, Louis (1962). Strategy and Command – The First Two Years (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. LCCN 61-60001. OCLC 63151391. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- Rodman, Matthew K. (2005). A War of Their Own: Bombers over the Southwest Pacific (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Air University. ISBN 1-58566-135-X. OCLC 475083118. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2012. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- Rogers, Paul P. (1990). MacArthur and Sutherland: The Good Years. New York City: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-92918-3.

- Stephens, Alan (2001). The Royal Australian Air Force: A History. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-555541-4.

- Wheeler, Gerald E. (1994). Kinkaid of the Seventh Fleet: A Biography of Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid, U.S. Navy. Washington, D.C.: Naval Historical Center. ISBN 0-945274-26-2. OCLC 31078997.

- Wolk, Herman S. (September 1987). "The Other Founding Father" (PDF). Air Force Magazine. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- Wolk, Herman S. (1988). "George C. Kenney: MacArthur's Premier Airman". In Leary, William M (ed.). We Shall Return! MacArthur's Commanders and the Defeat of Japan, 1942–1945. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-9105-8. OCLC 17483104.

Further reading

- Dean, Peter (2018). MacArthur's Coalition: US and Australian Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, 1942-1945. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-2605-2. OCLC 1012716132.