Spanish–Algerian War (1775–1785)

| Spanish–Algerian War (1775–1785) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish-Barbary wars | |||||||

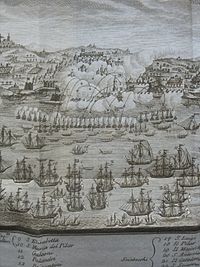

A Spanish Xebec facing two Algerian brave ships. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1775: 20,000 men 7 ships of the line 12 frigates 27 gunboats 5 hulks 9 feluccas 4 mortar boats 7 galleys 3 smaller warships 230 transports[1] 1783: 76 ships 1784: 9 ships of the line 11 frigates 14 xebecs 90 smaller warships[2] |

Total: 4,000 Janissaries 15,000 camelry 14,000 infantry 2 demi-galleys 2 xebecs 6 gunboats 1 felucca[3] 70 galliots, gunboats, and other minor ships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5,000 dead 2,000 wounded [4] |

300 dead (1775) unknown total deaths 65 galiots and gunboats destroyed[5] | ||||||

The Spanish–Algerian War (1775–1785) was a conflict between the Spanish Empire and the Deylik of Algiers.

An attempted peace treaty in 1766 resulted only in an exchange of captives. Spain officially declared war in 1775, launching an ill-fated invasion led by Alejandro O'Reilly that was repelled with significant losses, despite support from Tuscan forces. Algerian privateering increased post-invasion, and Spain's attempts at peace through diplomacy and bribery were unsuccessful. Two separate bombardments of Algiers by Rear admiral Antonio Barceló in 1783 and 1784 inflicted limited damage and failed to compel Algerian surrender. The war concluded in 1785 with a treaty that required Spain to pay 1,000,000 Pesos in war reparations but failed to end hostilities or piracy.

Background

Spain and Algeria were in a de facto constant state of conflict, ever since the Spanish-Algerian War (1504–1512), albeit war was rarely declared. Spain was especially crippled by this since Algerine pirates had been constantly harassing the Spanish coast, Spain fought multiple wars with Algeria, but they were never able to end the local piracy once and for all. On top of that Spain held both Oran and Mers El Kébir, following their decisive victory in 1732.[6] In 1766, some time after Baba Mohammed ben-Osman (also known as Muhammad V) was elected by the diwan of Algiers to be the Dey of Algiers, Spain attempted to sign a peace treaty with them, but that only ended in the exchange of captives in 1767, and 1768.[7] In 1775, after raids didn't stop, Spain de jure declared war, and in May, sent Alejandro O'Reilly to lead an expedition against Algiers.

The War

The Invasion of Algiers (1775)

By June the task force that had been assembled was enormous, with seven ships of the line, twelve frigates, twenty-seven gunboats, five hulks, nine feluccas, four mortar boats, seven galleys and three smaller warships, along with two hundred and thirty transport ships. Twenty thousand soldiers, sailors and marines completed the complement and it set course from the port of Cartagena for Algiers, reaching its destination by the beginning of July. On the way, they joined forces with the small fleet of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany led by Tuscan admiral Sir John Acton.[1] On July 5, the combined Spanish and Tuscan force reached Algiers, and O'Reilly made the decision to land troops to capture the city. The Spanish troops landed in two waves, but became deeply uncomfortable by the sweltering summer heat. Spanish admiral Antonio Barceló instructed his warships to protect the landing craft as they approached, but despite the bays shallow water he stuck to the coast as close as possible to maximize the effectiveness of his ships. Despite the strict instructions that O'Reilly gave to his troops, the pilots of the landing craft mistakenly chose the wrong landing area and the artillery guns being transported on the landing craft became stuck fast in the dunes of the beach after being landed, making them totally unusable for combat. Once ashore, the Spanish were met initially with light Algerian resistance, mainly because a feigned retreat by the forces advancing from Algiers. The latter had been massively augmented by warrior tribesmen from the interior, who sent forces to Algiers after having been alerted by intelligence sent by Berber merchants in Marseilles who had followed the course of Spanish military preparations during the spring of 1775.[8]

The Spanish advanced forwards to engage the seemingly retreating Algerian forces, and moved further inland. However, the Algerians drew the Spanish into a specially chosen location where they could ambush and attack them from cover. By now the Spanish had realized the position they were in, at the same time the Algerians sprung their trap. However, by the time the Spanish realized they were surrounded, it was too late for them.[9] Unable to hold an effective line of resistance, the Spanish forces were routed, returning in chaos to their ships. The losses were huge; suffering nearly 3,000 casualties, including five generals killed and fifteen wounded (with one of these being Bernado de Galvez), and abandoning to the Algerians no fewer than 15 artillery pieces and some 9000 other weapons.[4] Henry Swinburne, a British travel writer wrote that the Spanish would have been "broken and slaughtered to a man... had not Mr. Acton, the Tuscan commander, cut his cables, and let his ships drive in to shore just as the enemy was coming on us full gallop. The incessant fire of his great guns, loaded with grape-shot, not only stopped them, but obliged them to retire with great loss."[10] 2,000 Spaniards were captured as many were cut off from the boats that would have allowed them to return to their ships. O'Reilly had to wait for a month to negotiate their return. He then wanted to retaliate by bombarding Algiers from the sea, but he learned that he had only enough provisions on board to last for an immediate return to Spain. O'Reilly and the Spanish fleet withdrew to Alicante with his reputation now in tatters.

Aftermath

The Algerine privateering against Spanish vessels increased following the disastrous invasion of Algiers in 1775.[11] Spain tried to reach a peace agreement with the Ottoman Regency with the aim of securing their commercial traffic along the Mediterranean. Don Juan de Bouligny was sent to Constantinople in 1782 and managed to obtain a friendship and commercial agreement with Sultan Abdul Hamid I.[11] The Regency, nevertheless, denied to accept the treaty. The Dey, influenced by several of his officers, the fasnachi, the treasurer, the focha, the Codgia of the cavalry and the Aga of the infantry, opted for war, ignoring the recommendations of his naval officers.[12] The Spanish chief minister, the Count of Floridablanca, then tried in vain to bribe the Dey with gold to open negotiations for peace.[12]

King Charles III, feeling that the national pride of Spain had been offended by the Algerines, resolved to punish them by bombarding their town.[13] Rear admiral Antonio Barceló was appointed to carry out the attack. Though he was by far the most capable naval officer of Spain and one of the few who had risen through the ranks by merit, Barceló's designation was coldly received both by the Spanish court and military.[14] The Rear admiral was old and illiterate and of humble extraction, which, together with his naval victories, earned him the envy of most of the senior Spanish officers.[14]

The Bombardment of Algiers (1783)

Barceló sailed from Cartagena on July 3 ahead of 5 ships of the line, 4 frigates and 68 small vessels, including gunboats and bomb vessels. The Algerines had no more than 2 demi-galleons of 5 guns each, a felucca of 6, two xebecs of 4 guns each, and 6 gunboats carrying 12 and 24-pounders to oppose them.[3] On 29 July the Spanish fleet came in sight of the town and two days later Barceló formed his line of battle and made the necessary dispositions for the attack. The bomb-ketches and gunboats, supported by xebecs and other vessels, formed the vanguard, the whole being covered by the ships of line and frigates.[15]

The cannonade and bombardment commenced at 14:30, and continued without intermission till sunset.[15] The attack was renewed on the following, and on every succeeding day until the 9th, when it was resolved at a council of war, for sufficient reasons, to return immediately to Spain.[15] In the course of these attacks 3732 mortar shells and 3833 rounds of shot were discharged by the Spaniards, and the Algerines returned 399 mortar shells and 11,284 rounds of shot. This vast expenditure of ammunition produced no corresponding effect on either side: the town was repeatedly set on fire, but the flames were soon subdued.[15]

Following the example of the Great Siege of Gibraltar, the garrison used red-hot balls, but they did not produce a similar effect. The Algerines made several bold sallies with their small vessels, but were constantly repulsed by the superiority of fire from the fleet.[15] While the Dey had taken refuge at his citadel, the weight of the defense was sustained by an improvised militia composed mostly of teenagers. 25 Algerine heavy guns purchased in Denmark had blown up during the battle due to their misuse or bad conditions.[16] In addition, 562 buildings were destroyed or damaged by the bombardment, an insignificant figure given that Algiers consisted of 5,000 buildings and that the whole town was exposed to the Spanish fire.[16] Otherwise, only one gunboat was lost by the defenders. The Spanish casualties were also minimum: 26 killed and 14 wounded.[17]

The Bombardment of Algiers (1784)

In Cartagena, Barceló had finished preparations for a new expedition. His fleet consisted of four 80-gun ships of line, four frigates, 12 xebecs, 3 brigs, 9 small vessels, and an attacking force of 24 gunboats armed with pieces of 24 pounds, 8 more with 18 pounds' pieces, 7 lightly armed to board the Algerian vessels, 24 armed with mortars, and 8 bomb vessels with 8 pound pieces.[18] The expedition was financed by Pope Pius VI and supported by the Navy of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which provided two ships of the line, three frigates, two brigs and two xebecs under Admiral Bologna, by the Order of Malta, which provided a ship of line, two frigates and five galleys, and by that of Portugal, which provided two ships of line and two frigates under Admiral Ramires Esquível. These last joined the allied fleet later and arrived in the middle of the bombardment.[18]

On 28 June, having entrusted itself to the Virgen del Carmen, the Allied fleet sailed from Cartagena, arriving off Algiers on 10 July.[18] Two days later at 8:30 AM, the bombardment began with the Spanish ships opening fire. It was kept up until 4:20 PM, during which time about 600 bombs, 1,440 cannonballs and 260 shells were fired over the city, compared to 202 bombs and 1,164 cannonballs fired by the Algerians.[18] Major damage to the city and its fortifications and a large fire were observed. An attack by light vessels of the Algerian fleet, composed of 67 ships, was repulsed, four of them being destroyed.[18] The Allied casualties were minimal: 6 killed and 9 wounded, most of them due to accidents with the fuses of the bombs.[18] Gunboat No. 27, commanded by the Neapolitan ensign José Rodríguez, exploded accidentally, killing 25 sailors.[19]

The treaty

Algiers refused to give in to Spanish demands and piracy continued. At last in 1785, a peace treaty was concluded, forcing Spain to pay 1,000,000 Pesos as war reparations to Algiers, the signing of the treaty did not end hostilities and skirmishes continued.[7]

References

- ^ a b Jaques p. 34

- ^ Juan Vidal/Martínez Ruiz pg. 329

- ^ a b Pinkerton 1809, p. 461.

- ^ a b Wolf p. 322

- ^ Rodríguez González p. 211

- ^ Doncel p.264

- ^ a b "RELATIONS ENTRE ALGER ET CONSTANTINOPLE SOUS LA GOUVERNEMENT DU DEY MOHAMMED BEN OTHMANE PACHA ( ), SELON LES SOURCES ESPAGNOLES". docplayer.fr (in French). Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ^ Powell p. 886

- ^ Houtsma p. 259

- ^ Swinburne pg. 61

- ^ a b Sánchez Doncel 1991, p. 274.

- ^ a b Conrotte & Corrales 2006, p. 165.

- ^ Conrotte & Corrales 2006, p. 160.

- ^ a b Conrotte & Corrales 2006, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e Cust 1859, p. 14.

- ^ a b Conrotte & Corrales 2006, p. 163.

- ^ Fernández Duro 1902, p. 346.

- ^ a b c d e f Don Antonio Barceló, el "Capitán Toni".

- ^ Fernández Duro pg. 346

Bibliography

- Conrotte, Manuel; Corrales, Eloy Martín (2006). España y los países musulmanes durante el ministerio de Floridablanca (in Spanish). Spain: Editorial Renacimiento. ISBN 84-96133-57-5.

- Cust, Edward (1859). España Annals of the wars of the eighteenth century, compiled from the most authentic histories of the period: 1783-1795. London: Mitchell's Military Library.

- Fernández Duro, Cesáreo (1902). Armada española desde la unión de los reinos de Castilla y de León. Vol VII (in Spanish). Madrid: Sucesores de Rivadeneyra.

- Pinkerton, John (1809). A general collection of the best and most interesting voyages and travels in all parts of the world: many of which are now first translated into English ; digested on a new plan. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme.

algiers barceló.

- Sánchez Doncel, Gregorio (1991). Presencia de España en Orán (1509-1792) (in Spanish). Toledo: I.T. San Ildefonso. ISBN 978-84-600-7614-8.