Symphony No. 3 (Mahler)

| Symphony No. 3 | |

|---|---|

| by Gustav Mahler | |

Mahler in 1898 | |

| Key | D minor |

| Composed | 1896: Steinbach |

| Published | 1898

|

| Movements | 6 |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 9 June 1902 |

| Location | Krefeld |

| Conductor | Gustav Mahler |

| Performers | Orchester des Allgemeines Deutschen Musikvereins |

The Symphony No. 3 in D minor by Gustav Mahler was written in sketch beginning in 1893, composed primarily in 1895,[1] and took final form in 1896.[2] Consisting of six movements, it is Mahler's longest composition and is the longest symphony in the standard repertoire, with a typical performance lasting around 95 to 110 minutes. It was voted one of the ten greatest symphonies of all time in a survey of conductors carried out by the BBC Music Magazine.[3]

Structure

In its final form, the work has six movements, grouped into two parts:

- Kräftig. Entschieden (Strong and decisive) D minor to F major

- Tempo di Menuetto Sehr mässig (In the tempo of a minuet, very moderate) A major

- Comodo (Scherzando) Ohne Hast (Comfortable (Scherzo), without haste) C minor to C major

- Sehr langsam—Misterioso (Very slowly, mysteriously) D major

- Lustig im Tempo und keck im Ausdruck (Cheerful in tempo and cheeky in expression) F major

- Langsam—Ruhevoll—Empfunden (Slowly, tranquil, deeply felt) D major

The first movement alone, with a normal duration of a little more than thirty minutes, sometimes forty, forms Part One of the symphony. Part Two consists of the other five movements and has a duration of about sixty to seventy minutes.

As with each of his first four symphonies, Mahler originally provided a programme of sorts to explain the narrative of the piece. He did not reveal the structure and content to the public. But, at different times, he shared evolving versions of a program for the third symphony with various friends: Max Marschalk, a music critic; violist Natalie Bauer-Lechner, a close friend and confidante; and Anna von Mildenburg, the dramatic soprano and Mahler's lover during the summer of 1896 when he was completing the symphony. Bauer-Lechner wrote in her private journal that Mahler said, "You can't imagine how it will sound!"[4]

In its simplest form, the program consists of a title for each of the six movements:

- "Pan Awakes, Summer Marches In"

- "What the Flowers in the Meadow Tell Me"

- "What the Animals in the Forest Tell Me"

- "What Man Tells Me"

- "What the Angels Tell Me"

- "What Love Tells Me"

Mahler, however, elaborated on this basic scheme in various letters. In an 1896 letter to Max Marschalk, he called the whole "A Summer's Midday Dream", and within Part One, distinguished two sections, "Introduction: Pan awakes" and "I. Summer marches in (Bacchic procession)".[5] In a June 1896 letter to Anna von Mildenburg, Mahler reaffirmed that he conceived the first movement in two sections: I. What the stony mountains tell me; II. Summer marches in.[6] In another letter to Mildenburg from Summer 1896, he said that "Pan" seemed to him the best overall title (Gesamttitel) for the symphony, emphasizing that he was intrigued by Pan's two meanings, a Greek god and a Greek word meaning "all".[7]

All these titles were dropped before publication in 1898.[5]

Mahler originally envisioned a seventh movement, "Heavenly Life" (alternatively, "What the Child Tells Me"), but he eventually dropped this, using it instead as the last movement of the Symphony No. 4.[8] Indeed, several musical motifs taken from "Heavenly Life" appear in the fifth (choral) movement of the Third Symphony.[5]: 276

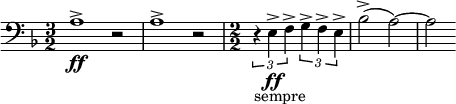

The symphony, particularly due to the extensive number of movements and their marked differences in character and construction, is a unique work. The opening movement, colossal in its conception (much like the symphony itself), roughly takes the shape of sonata form, insofar as there is an alternating presentation of two theme groups; however, the themes are varied and developed with each presentation, and the typical harmonic logic of the sonata form movement—particularly the tonic statement of second theme group material in the recapitulation—is changed.[clarification needed] The symphony starts with a fortissimo theme, stated by an 8-French horn choir. It is similar to the opening of the fourth movement of Brahms' first symphony with the same rhythm, but many of the notes are changed.

The opening gathers itself slowly into a rousing orchestral march. A solo tenor trombone passage states a bold (secondary) melody that is developed and transformed in its recurrences.

At the apparent conclusion of the development, several solo snare drums "offstage" play a rhythmic passage lasting about thirty seconds and the opening passage by eight horns is repeated almost exactly.

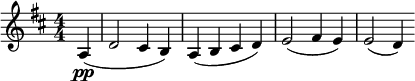

As described above, Mahler dedicated the second movement to "the flowers on the meadow". In contrast to the violent forces of the first movement, it starts as a graceful menuet, but also features stormier episodes.

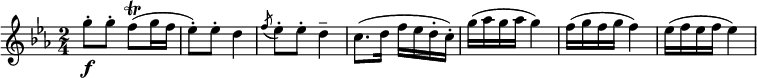

The third movement, a scherzo, with alternating sections in 2

4 and 6

8 meter, quotes extensively from Mahler's early song "Ablösung im Sommer" (Relief in Summer).[9]

In the trio section, the mood change from playful to contemplative occurs with an off-stage post horn (or flugelhorn) solo.

This posthorn episode closely resembles standardised posthorn signals in Austria and Prussia of the time.[10][11] The posthorn melody is suddenly interrupted (in measure 345) by a trumpet fanfare representing a literal quotation of the Austrian military signal for falling out (Abblasen).[12][13] Another important quotation in the movement is a Spanish folk melody of jota aragonesa used by Mikhail Glinka in Caprice brillante and by Franz Liszt in Rhapsodie espagnole. Most probably it borrowed here from Ferruccio Busoni's transcription of the Rhapsodie for piano and orchestra, as the harmonies are almost identical and passages are equally almost similar.[14][15] Busoni himself was the first to remark on this quotation in 1910.[16]

The reprise of the scherzo music is unusual, as it is interrupted several times by the post-horn melody.

At this point, in the sparsely instrumentated fourth movement, we hear an alto solo singing a setting of Friedrich Nietzsche's "Midnight Song" ("Zarathustra's roundelay") from Also sprach Zarathustra ("O Mensch! Gib acht!" ("O man! Take heed!")), with thematic material from the first movement woven into it.[17] The movement is punctuated by oboe glissandi, representing the cry of a night bird.[18]

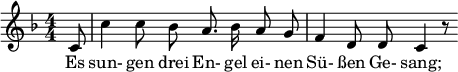

The cheerful fifth movement, "Es sungen drei Engel", is one of Mahler's Des Knaben Wunderhorn songs, (whose text itself is loosely based on a 17th-century church hymn, which Paul Hindemith later used in its original form in his Symphony "Mathis der Maler") about the redemption of sins and comfort in belief.

Here, a children's choir imitating bells and a female chorus join the alto solo.

Of the finale, Bruno Walter wrote,

In the last movement, words are stilled—for what language can utter heavenly love more powerfully and forcefully than music itself? The Adagio, with its broad, solemn melodic line, is, as a whole—and despite passages of burning pain—eloquent of comfort and grace. It is a single sound of heartfelt and exalted feelings, in which the whole giant structure finds its culmination.[This quote needs a citation]

The movement begins very softly with a broad D-major chorale melody in the strings, which slowly builds to a loud and majestic conclusion culminating on repeated D major chords with bold statements on the timpani.

The last movement in particular had a triumphant critical success. The Swiss critic William Ritter, in his review of the premiere given in 1902, said of the last movement: "Perhaps the greatest Adagio written since Beethoven". Another anonymous critic writing in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung wrote about the Adagio: "It rises to heights which situate this movement among the most sublime in all symphonic literature". Mahler was called back to the podium 12 times, and the local newspaper reported that "the thunderous ovation lasted no less than fifteen minutes".[19]

Instrumentation

The symphony is scored for large orchestra, consisting of the following:

Text

Fourth movement

Text from Friedrich Nietzsche's Also sprach Zarathustra: the "Midnight Song"

O Mensch! Gib Acht!

Was spricht die tiefe Mitternacht?

"Ich schlief, ich schlief —,

aus tiefem Traum bin ich erwacht: —

Die Welt ist tief,

und tiefer als der Tag gedacht.

Tief ist ihr Weh —,

Lust — tiefer noch als Herzeleid.

Weh spricht: Vergeh!

Doch all' Lust will Ewigkeit —,

— will tiefe, tiefe Ewigkeit!"

O Man! Take heed!

What says the deep midnight?

"I slept, I slept —,

from a deep dream have I awoken: —

the world is deep,

and deeper than the day has thought.

Deep is its pain —,

joy — deeper still than heartache.

Pain says: Pass away!

But all joy seeks eternity —,

— seeks deep, deep eternity!"

Fifth movement

Text from Des Knaben Wunderhorn

Es sungen drei Engel einen süßen Gesang,

mit Freuden es selig in dem Himmel klang.

Sie jauchzten fröhlich auch dabei:

daß Petrus sei von Sünden frei!

Und als der Herr Jesus zu Tische saß,

mit seinen zwölf Jüngern das Abendmahl aß,

da sprach der Herr Jesus: "Was stehst du denn hier?

Wenn ich dich anseh', so weinest du mir!"

"Und sollt' ich nicht weinen, du gütiger Gott?

Ich hab' übertreten die zehn Gebot!

Ich gehe und weine ja bitterlich!

Ach komm und erbarme dich über mich!"

"Hast du denn übertreten die zehen Gebot,

so fall auf die Knie und bete zu Gott!

Liebe nur Gott in alle Zeit!

So wirst du erlangen die himmlische Freud'."

Die himmlische Freud' ist eine selige Stadt,

die himmlische Freud', die kein Ende mehr hat!

Die himmlische Freude war Petro bereit't,

durch Jesum und allen zur Seligkeit.

Three angels sang a sweet song,

with blessed joy it rang in heaven.

They shouted too for joy

that Peter was free from sin!

And as Lord Jesus sat at the table

with his twelve disciples and ate the evening meal,

Lord Jesus said: "Why do you stand here?

When I look at you, you are weeping!"

"And should I not weep, kind God?

I have violated the ten commandments!

I wander and weep bitterly!

O come and take pity on me!"

"If you have violated the ten commandments,

then fall on your knees and pray to God!

Love only God for all time!

So will you gain heavenly joy."

The heavenly joy is a blessed city,

the heavenly joy that has no end!

The heavenly joy was granted to Peter

through Jesus, and to all mankind for eternal bliss.

Tonality

Peter Franklin in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians represents the symphony's progressive tonal scheme as 'd/F—D'.[20] More casually it is described as being in D minor. The first movement certainly begins in this key but, by its end, has defined the relative F major as the tonic. The finale concludes in D major, the tonic major, which is not unusual for minor key, multi-movement works. Throughout the symphony, traditional tonality is employed in an enterprising manner with clear purpose [vague].

Editions and performance

The piece is performed in concert less frequently than Mahler's other symphonies[citation needed], due in part to its great length and the huge forces required. Despite this, it is a popular work and has been recorded by most major orchestras and conductors.

When it is performed, a short interval is sometimes taken between the first movement (which alone lasts around half an hour) and the rest of the piece. This is in agreement with the manuscript copy of the full score (held in the Pierpont Morgan Library, New York), where the end of the first movement carries the inscription Folgt eine lange Pause! ("there follows a long pause").[21] The inscription is not found in the score as published.

The Adagio movement was arranged by Yoon Jae Lee in 2011 for a smaller orchestra. This version was premiered by Ensemble 212 with Lee as conductor in New York on the eve of the tenth anniversary of the September 11 attacks. Subsequently, Lee arranged the five remaining movements for smaller orchestra as part of his Mahler Chamber Project. The orchestral reduction of the entire symphony was premiered in October 2015 by Ensemble 212, mezzo-soprano Hyona Kim, and the Young New Yorkers' Chorus Women's Ensemble.

The second movement was arranged by Benjamin Britten in 1941 for a smaller orchestra. This version was published by Boosey & Hawkes as What the Wild Flowers Tell Me in 1950.

In other media

The final movement was used as background music in one episode of the 1984 television series Call to Glory and on an episode of the BBC's Coast programme, during a description of the history of HMS Temeraire. It also served as background music during the "Allegory" segment of the Athens 2004 Summer Olympics opening ceremony cultural show.[citation needed] The final movement is also played during Coleman Silk's funeral in Philip Roth's novel The Human Stain.[22]

A section from the fourth movement "Midnight Song" features in Luchino Visconti's 1971 film Death in Venice (which also features the Adagietto from the Fifth Symphony), where it is presented as the music that Gustav von Aschenbach composes before he dies.

The work is also referenced in the pop singer Prince's song "Good Love" ("Gustav Mahler #3 is jamming on the box") from his Crystal Ball album and the Bright Lights, Big City soundtrack.[23]

Premieres

- First performance of the second movement: 9 November 1896 Berlin, conducted by Arthur Nikisch (repeated by him in Leipzig on 21 January 1897).

- Performance of second, third and sixth movements: 9 March 1897, Berlin, conducted by Felix Weingartner.

- Premiere of the complete symphony: 9 June 1902, Krefeld, cond. by the composer. (Between 1902 and 1907 Mahler conducted his symphony 15 times, cf. "Mahler's Concerts", by Knud Martner, New York 2010, p. 341).

- Dutch premieres: 17 October 1903 in Arnhem; five days later Mahler led the Amsterdam premiere with the Concertgebouw Orchestra.

- American premiere: 9 May 1914, Cincinnati May Festival, cond. by Ernst Kunwald.

- New York City premiere: 28 February 1922, New York Philharmonic cond. by Willem Mengelberg.

- British premiere: 29 November 1947, BBC Symphony Orchestra in a broadcast cond. by Adrian Boult; this was not recorded by the BBC, but an off-air recording was made on acetate discs and transferred to CD in 2008: the earliest extant recording of the symphony.

- First radio studio recording: 1950, Hilde Rössel-Majdan, choirs, Vienna Symphony cond. by F. Charles Adler.

- First commercial recording: 27 April 1952 Hilde Rössel-Majdan, choirs, Vienna Symphony cond. by F. Charles Adler on the SPA label. It is available for streaming on Spotify.

- First public performance in Britain: 28 February 1961, St. Pancras Town Hall, cond. by Bryan Fairfax.

References

- ^ Walter, Bruno; Tanner, Michael (26 November 2017). Gustav Mahler. p. 32.[full citation needed]

- ^ Constantin Floros, Gustav Mahler: The Symphonies, translated by Vernon Wicker (Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1993) ISBN 1-57467-025-5.

- ^ "Beethoven's Eroica voted greatest symphony of all time | Music". The Guardian. 4 August 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ^ Natalie Bauer-Lechner, Recollections of Gustav Mahler, English translation by Dika Newlin (1980, Faber & Faber), 52.

- ^ a b c Jens Malte Fischer, Gustav Mahler, English translation by Stewart Spencer, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), 275.

- ^ Willnauer, Franz, ed. (2006). Gustav Mahler: 'Mein lieber Trotzkopf, meine süße Mohnblume': Briefe an Anna von Mildenburg. Vienna: Paul Zsolnay Verlag. p. 132. ISBN 3-552-05389-1.

- ^ Willnauer 2006, p. 142.

- ^ Cooke, Deryck (1980). Gustav Mahler: An Introduction to his Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-521-23175-2.

- ^ Cooke 1980, p. 64.

- ^ Freeze 2010, p. 136.

- ^ Hiller, Albert. Das große Buch vom Posthorn. Wilhelmshaven: Heinrichshofens Verlag, 1985. pp. 80–81

- ^ Emil Rameis, Die österreichische Militärmusik—von ihren Anfängen bis 1918, rev. ed., ed. Eugen Brixel in Alta Musica 2 (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1976), 183, 188

- ^ Jason Stephen Heilman, O du mein Österreich: Patriotic Music and Multinational Identity in the AustroHungarian Empire (PhD diss., Duke University, 2009), 198.

- ^ Freeze, Timothy David (2010). Gustav Mahler's Third Symphony: Program, Reception, and Evocations of the Popular (PDF) (Doctor of Philosophy (Music Musicology)). University of Michigan. p. 113. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ Morten Solvik, "Biography and Musical Meaning in the Posthorn Solo of Mahler's Third Symphony", in Neue Mahleriana: Essays in Honour of Henry-Louis de La Grange on his Seventieth Birthday, ed. Günther Weiß (Bern: Peter Lang, 1997), 340–344, 356–359.

- ^ Ferruccio Busoni, Von der Einheit der Musik: Von Dritteltönen und junger Klassizität, von Bühnen und anschliessenden Bezirken (Berlin: Max Hesse, 1922), 152.

- ^ Lee, Jennifer. "Time as a circular spectrum and the retrospective device in Gustav Mahler's Symphony no. 3 (1895–1896)" (PDF). Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Cooke 1980, p. 65.

- ^ Strawser, Dick (6 April 2011). "Dr. Dick's Harrisburg Symphony Blog: Attending the World Premiere of Mahler's Symphony No. 3".

- ^ Franklin, Peter (2001). "Mahler, Gustav". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40696. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- ^ See facsimile reproduced in the "Philharmonia" pocket score (Universal Edition)

- ^ Roth, Philip (2000). The Human Stain. United States: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 312–313. ISBN 0-618-05945-8.

- ^ "Prince – Good Love" – via genius.com.

Further reading

- Barham, Jeremy. 1998. "Mahler's Third Symphony and the Philosophy of Gustav Fechner: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Criticism, Analysis, and Interpretation". Ph.D. thesis. University of Surrey.

- Filler, Susan M. 1976. "Editorial Problems in Symphonies of Gustav Mahler: A Study of the Sources of the Third and Tenth". PhD diss. Evanston: Northwestern University.

- Franklin, Peter. 1977. "The Gestation of Mahler's Third Symphony". Music & Letters 58:439–446.

- Franklin, Peter. 1999. "A Stranger's Story: Programmes, Politics, and Mahler's Third Symphony". In The Mahler Companion, edited by Donald Mitchell and Andrew Nicholson, 171–186. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816376-3 (cloth) ISBN 978-0-19-924965-7 (pbk).

- Franklin, Peter. 1991. Mahler: Symphony No. 3. Cambridge Music Handbooks. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37947-2.

- Johnson, Steven Philip. 1989. "Thematic and Tonal Processes in Mahler's Third Symphony". Ph.D. diss. Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles.

- La Grange, Henry-Louis de. 1995. Gustav Mahler, vol. 3: "Triumph and Disillusion (1904–1907)", revised edition. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-315160-4.

- Micznik, Vera. 2005. " 'Ways of Telling' in Mahler's Music: The Third Symphony as Narrative Text", In Perspectives on Gustav Mahler, edited by Jeremy Barham, 295–344. Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate Publishers. ISBN 9780754607090.

- Pavlović, Milijana. 2010. "Return to Steinbach: An Unknown Sketch of Mahler's Third Symphony". Il Saggiatore Musicale 17:43–52.

- Reilly, Edward R. 1986. A Re-examination of the Manuscripts of Mahler's Third Symphony. In Colloque International Gustav Mahler: 25, 26, 27 janvier 1985, edited by Henry-Louis de La Grange, 62–72. Paris: Association Gustav Mahler.

- Williamson, John. 1980. Mahler's Compositional Process: Reflections on an Early Sketch for the Third Symphony's First Movement. Music & Letters 61:338–345.

External links

- Symphony No. 3 (Mahler): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

![\relative c' { \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"oboe" \clef treble \key a \major \time 3/4 \tempo "Tempo di Menuetto" \partial 4*1 e4->(\pp | a8_"zart" r a) r | b4->( | gis8 r gis) r a8.( b16 | gis8-.[ r16 fis-. e8-. r16 d-. cis8. fis16] | e8 r e) r }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/i/s/isuj5navz1n933evqduj2l3hrsd167u/isuj5nav.png)

![\relative c'' { \clef treble \key f \major \time 6/8 c4 c,8 f[ r16 c-. f8-.] | c'4.~ c4 \breathe c,8 | f4 f8 a[ r16 f-. a8-.] | c4.~c4 \breathe }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/1/8/18aio5hu45bdnyl59m35fofnt8fsy3v/18aio5hu.png)