Symphony No. 6 (Bruckner)

| Symphony No. 6 | |

|---|---|

| by Anton Bruckner | |

A portrait of Anton Bruckner | |

| Key | A major |

| Catalogue | WAB 106 |

| Composed | 1879 – 1881: |

| Dedication | Anton von Oelzelt-Newein and his wife Amy |

| Published |

|

| Recorded | 1950 Henry Swoboda, Vienna Symphony |

| Movements | 4 |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 26 February 1899 |

| Location | Graz |

| Conductor | Gustav Mahler |

| Performers | Vienna Philharmonic |

The Symphony No. 6 in A major, WAB 106, by Austrian composer Anton Bruckner (1824–1896) is a work in four movements composed between 24 September 1879, and 3 September 1881[1] and dedicated to his landlord, Anton van Ölzelt-Newin.[2] Only two movements from it were performed in public in the composer's lifetime.[3] Though it possesses many characteristic features of a Bruckner symphony, it differs the most from the rest of his symphonic repertory.[4] Redlich went so far as to cite the lack of hallmarks of Bruckner's symphonic compositional style in the Sixth Symphony for the somewhat bewildered reaction of supporters and critics alike.[5]

According to Robert Simpson, though not commonly performed and often thought of as the ugly duckling of Bruckner's symphonic body of work, the symphony nonetheless makes an immediate impression of rich and individual expressiveness: "Its themes are exceptionally beautiful, its harmony has moments of both boldness and subtlety, its instrumentation is the most imaginative he had yet achieved, and it possesses a mastery of classical form that might even have impressed Brahms."[6]

Historical context

By the time Bruckner began composing his Symphony No. 6, only three of his symphonies had been performed. The recent premiere of his Third Symphony had been nothing short of disastrous, receiving an extremely negative, though not surprising review from Eduard Hanslick, given Hanslick's predilection for the works of Brahms.[7]

...his artistic intentions are honest, however oddly he employs them. Instead of a critique, therefore, we would rather simply confess that we have not understood his gigantic symphony. Neither were his poetic intentions clear to us...nor could we grasp the purely musical coherence. The composer...was greeted with cheering and was consoled with lively applause at the close by a fraction of the audience that stayed to the end...the Finale, which exceeded all its predecessors in oddities, was only experienced to the last extreme by a little host of hardy adventurers.[7]

The composition of his Symphony No. 4 marked the beginning of what some refer to as the "Major Tetralogy", Bruckner's four symphonies composed in major keys.[8] In fact, this tetralogy was part of an entire decade in Bruckner's compositional history devoted to large-scale works written in major keys, a fact of note considering that all of his previous symphonies and foremost choral works were composed in minor keys.[9] The composition of his String Quintet and the Sixth Symphony marked the beginning of a new compositional period for Bruckner within the realm of the "Major Tetralogy".[10] However, the Sixth Symphony has extensive ties to the Fourth and Fifth Symphonies and is considered to have been composed as a reflective, humanistic response to its two direct symphonic predecessors. It has even been dubbed the Philosophical symphony by critics for this reason.[11]

Compositional hallmarks

Bruckner's symphonies encompass many techniques but the one unwavering hallmark of his symphonic compositions is a singular formal pattern that underwent very little variation over the course of his symphonic repertory. In fact, their four extended movements are indebted to the structure and thematic treatment in the late works of Beethoven.[12] The only large-scale diversion from this formal scheme in the Sixth Symphony is Bruckner's use of sonata form in the second movement instead of his usual large-scale ternary form.[13]

Thematically speaking, there are two distinct varieties of themes in Bruckner's symphonies. First, there are themes that are clearly defined in shape and then there are the themes that operate more as motives with a shorter length and a more open-ended shape, as is typical of the Sixth Symphony.[14] Another characteristic thematic feature of Bruckner's symphonies is the intimate relationship between the outer two movements, though there is typically more of an emphasis on thematic contrast within the first movement.[12] Specifically, the amplification of the exposition of the first movement consists of two subsidiary themes as well as the primary theme, which are subsequently developed, a technique that is considered uniquely Brucknerian.[15]

Other characteristics that are found in Bruckner's symphonies (especially the Sixth) include the extensive treatment of the dominant seventh chord as a German sixth chord in a new key, usage of cadences as a decisive factor in daring modulations, the treatment of organ points as pivotal to the harmony and structure, chains of harmonic sequences, and, most notably, extensive use of rhythmic motives, especially the characteristic Bruckner rhythm, a rhythm consisting of two fourths and three quarter notes, or vice versa.[16] This rhythm dominated most of the Fourth Symphony and was practically nonexistent in the Fifth Symphony, but becomes nothing short of a driving force in the Sixth Symphony; the metric complexities generated by this unique rhythmic grouping are more pronounced in the first movement of the Sixth Symphony than in any of Bruckner's other compositions.[17]

Orchestration

The orchestration of the Sixth Symphony complies with Bruckner's customary, albeit peculiar, techniques. Just as in his other symphonic works, there are no marks of extreme virtuosity apparent in the score and the lines are straightforward.[18] The Sixth Symphony is scored for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, one bass tuba, timpani, and strings. Bruckner commonly alternates between solo and tutti sections, as well as layering instruments to provide texture and show different subject groups.[19]

Forms, themes, and analysis

The symphony has four movements:

I. Majestoso

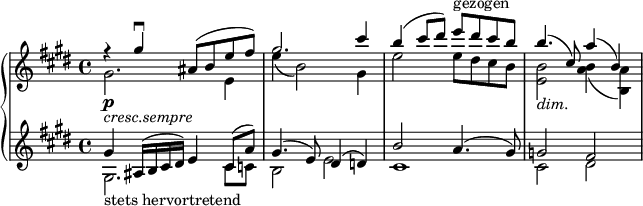

Bruckner labels this movement "Majestoso", not the conventional "Maestoso", probably from his Latin (from "Maiestas" – sovereign power). The movement, in obvious sonata form, opens with the characteristic 'Bruckner rhythm' played in the violins, though Bruckner is careful to maintain the enigmatic atmosphere by indicating a bowing that keeps the bow on the string and therefore prohibits the rhythmic figure from becoming too lively.[20] One then hears the quietly intense main theme, a paraphrase of the main theme of Bruckner's own Symphony No. 4, stated in the low strings and juxtaposed against the pulsating rhythm in the violins:[21]

The key is A major when the first theme enters; however, the mystery is heightened by notes outside the realm of A major tonality that appear in the melodic line, namely the pitches G, B♭ and F, Neapolitan inflections that will have large-scale tonal effects that come to fruition later in the symphony. The counterstatement of the theme appears (bar 25) in fortissimo, a long-established classical technique that Bruckner had yet to use at the beginning of a symphony.[20]

The second theme group is more complex than the primary theme. The first theme of this group is a confident melody in the violins in which Bruckner employs mixed rhythms:[22]

The second theme in this group, an expressive, lyrical motif (bar 69) is first heard in D major, closely followed by a statement in F major and a richly orchestrated statement in E major, the dominant of the movement's original A major. The third theme group, beginning with a militaristic statement of the Bruckner rhythm, now appears, followed by modulations ending in the dominant (E major) and segueing into the development section:[23]

The development is shorter and less complex than one usually finds in Bruckner's symphonic first movements; however, it plays a substantial role in the overall harmonic structure of the movement. From the outset (bar 159), the violins play an inversion of the main theme, though the Bruckner rhythm that accompanied it in the exposition is absent.[24] Instead, the development is propelled throughout by the triplet motif that first appeared in the third subject of the exposition.[25] Harmonically, the development encompasses a myriad of modulations, abruptly traversing between E♭ and A major, seemingly signaling the beginning of the recapitulation.[26]

The beginning of the recapitulation is, in fact, a climax, serving as both the end of the development and the beginning of the recapitulation, marking the first time in symphonic literature that this has occurred.[11] If not for this climactic moment, one could have trouble identifying the exact moment of recapitulation as the return of the tonic and the return of the primary theme do not coincide (in fact, there are 15 bars in between the two events).[27] In true Bruckner form, it encompasses a complete restatement of the theme groups from the exposition and is otherwise uneventful, setting the stage for the coda which Donald Tovey described as one of Bruckner's greatest passages.[28] In the Coda, Bruckner passes through the entire spectrum of tonality, leaving no key unsuggested; however, he establishes no tonal center except for A major.[28] The opening phrase of the first theme appears throughout, joined (bar 345) by the rhythmic motive from the beginning. An exultant final statement of that theme and the completion of a massive plagal cadence signal the end of the first movement.[29]

II. Adagio: Sehr feierlich (Very solemnly)

The second movement is in obvious sonata form, the only example of a sonata structure Adagio in Bruckner's symphonies, apart from that of the "nullified" Symphony in D minor[30] and the early draft of the Adagio of the First Symphony, dating from 1865.[25] Simpson went so far as to describe the movement as the most perfectly realized slow sonata design since the Adagio of Beethoven's Hammerklavier sonata[31] The movement opens with a theme in the strings, a yearning love song that is joined (bar 5) by a mournful lament on the oboe:

Simpson points out that the frequent Neapolitan inflections of the first movement are expanded here, beginning with the B♭ and F in the primary melodic line that make it natural that the movement should be in F major, though the opening initially ambiguously suggests B♭ minor.[31] After a brief transitional passage, there is a modulation to E major that marks the introduction of the second theme, a soaring, untroubled love song (bar 25):[32]

The third theme (bar 53) is characteristic of a funeral march, combining C minor and A♭ major and providing a somber contrast to the preceding love song:

The dotted rhythm in its first bar calls to mind the oboe lament from the beginning of the movement. Doernberg described this sad turn to A♭ major as the kind of music Gustav Mahler always wished to achieve, citing Bruckner as anticipatory to Mahler in this respect.[33]

There is a brief developmental section (bar 69) that includes modulation on the primary theme as well as inversions of the oboe lament. There is a recapitulation of all three themes (bar 93) though the orchestration is different, with the former violin theme (primary theme) now appearing in the horn and subsequently in the woodwinds. The second theme is recapitulated in its entirety in the tonic followed by a very short reappearance of the third theme.[33]

Finally, a transition over a dominant pedal (a Bruckner hallmark) leads to the Coda that Simpson referred to as the fine-drawn consolatory coda that is one of Bruckner's best.[34] At bar 157 one hears the last statement of the primary theme with the movement ending in its tonic, F major, in a state of "perfect serenity."[35]

III. Scherzo: Nicht schnell (Not fast) — Trio: Langsam (Slowly)

The A minor third movement is unlike any other composed by Bruckner; it is slower than usual and the tense character often associated with his Scherzi is often shadowed and muted, although there are movements of brilliance.[34] However, the most prominent feature is the lack of a striking Scherzo theme; instead one finds three contrasting rhythmical motives juxtaposed from the very beginning and united throughout the majority of the movement.[36] Its steady 3

4 time is pervaded, once again, by triplets throughout, often giving the impression of 9

8 and creating a broader sense of movement that is extremely deliberate, especially for a scherzo movement:[34]

There is a certain degree of harmonic ambiguity throughout, but nothing that compares to the opening of the first movement. One of the most fascinating features of the harmonic structure is Bruckner's avoidance of a root position tonic chord for much of the movement.[37] The first twenty bars of the movement once again rest on a dominant pedal and when the bass finally moves to the tonic pitch (A), it is not a root position tonic chord; instead, it acts as the bottom of a first inversion chord of F major (bar 21).[34]

In the development, one sees the addition of a new motif and harmonically, the section centers around D♭ major, G♭ major, and B♭ minor, all closely related keys but ones that are isolated from the tonic (A minor). The dominant of A minor is reached (bar 75) and here, the recapitulation begins, once again over a dominant pedal. It is important to note that there has still not been a root chord of A minor. This elusive A minor root chord finally appears at the end of the recapitulation leading into the C major Trio section.[38]

The slow trio is in the style of a Ländler, an Austrian folk dance and, according to Williamson, confirms that in Bruckner's works, it [the trio] is a place for construction in tone color as in the moment when horn and pizzicato strings compete on the same rhythmic figure:[39]

In fact, this dialogue between pizzicato strings, horn and woodwinds is central to the texture of the whole Trio section. Although the key is C major, there are moments of harmonic ambiguity, as in the preceding movements. At one point (bar 5), the strings point towards D♭ major while the woodwinds attempt to assert A♭ major by quoting the inversion of the main theme of Symphony No. 5 that is in A♭ major.[37] The scherzo returns in its entirety at the end of the trio, adhering to a typical large-scale ternary structure.

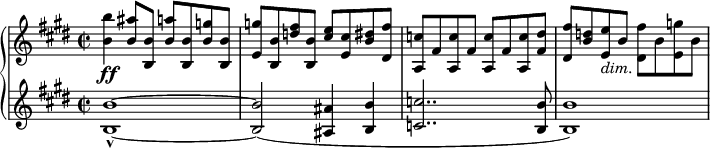

IV. Finale: Bewegt, doch nicht zu schnell (With motion, but not too fast)

Watson characterized the Finale as a steady, organic assertion of A major against its Neapolitan relatives. However, this sonata form movement begins with a theme in Phrygian A minor that once again stresses Neapolitan relationships with the obvious presence of the flat sixth (the pitch being F♮):[40]

The horns and trumpets interrupt with statements in A major (bar 22) but the theme is undeterred; four bars later they once again interrupt the theme and this time succeed in establishing A major (bar 29). A second theme in C major eventually appears:

This is followed by a third theme (bar 125) that is derived from the oboe lament of the second movement:

During the development section the music continues to modulate through a variety of major keys, including F major, E♭ major and E major until finally returning to the tonic A major (bar 245), regarded as the start of the recapitulation.[41]

The Coda once again encompasses a broad range of keys and juxtaposes the primary theme with the main theme from the first movement.[42] A final massive statement of A major asserts itself (bar 397) seemingly out of nowhere, embodying Bruckner's amazing ability to establish the tonic without a doubt and without the kind of preparation one would normally expect.[43] This movement does not, nor was it intended to have the vast impact of the Finale of the Fifth Symphony, but it is infinitely more refined than the Finale of his Fourth Symphony.[6] According to Watson, the victorious conclusion of Bruckner's quest for a new and ideal finale form will be celebrated in his Eighth Symphony, but the Sixth Symphony's development is an eminent and profoundly satisfying landmark on that triumphant march.[44]

Revisions and editions

This is the only Bruckner symphony exempt from any revisions by the composer. The Fifth, Sixth and Seventh represent Bruckner's period of confidence as a composer and, along with the unfinished Ninth, are as a group the symphonies he did not extensively revise.[6]

The Sixth was first published in 1899, a task overseen by former Bruckner pupil Cyrill Hynais. This edition did encompass a few minute changes from Bruckner's original, including the repetition of the second half of the Trio in the third movement.

The next edition appeared only in 1935, from Robert Haas under Internationale Bruckner-Gesellschaft auspices. In 1952 Leopold Nowak, who took over Haas's job, published an edition that was a replicate of Bruckner's 1881 original score. In 1986 the IBG issued an "audit" of the efforts of Hynais, Haas and Nowak, and in 1997 it republished the Nowak.

Another edition has been issued by Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs for the Anton Bruckner Urtext Gesamtausgabe in 2015.

The version of the Sixth performed under the direction of Mahler for the 1899 premiere was never published;[1] Mahler had made substantial changes to the whole score before that performance, of course unsanctioned by the deceased Bruckner.[45] There exists also an inauthentic edition by Franz Schalk.

Critical and cultural reception

Criticism of Bruckner's Symphony No. 6 is similar to the critical response that his preceding symphonies had received. Whereas Bruckner considered his Sixth Symphony to be his "boldest symphony," it was not generally held in high regard.[46] In terms of interpretation, the Sixth Symphony has also been the unluckiest, with the vast majority of conductors ignoring Bruckner's specific tempo markings and throwing off the carefully planned balance of the movements.[47] One 2004 reviewer for The Musical Times referred to the inner movements of this symphony as "flawed but attractive enough" and dubbed the outer movements "burdensome."[48]

Hanslick, as usual, was without a doubt the harshest critic of them all. He was once quoted as saying, "whom I wish to destroy shall be destroyed," and Bruckner seems to have been a prime target.[7] After hearing the 1883 performance of the middle movements of the Sixth Symphony, Hanslick wrote:

It has become ever harder for me personally to achieve a proper relationship with these peculiar compositions in which clever, original, and even inspired moments alternate frequently without recognizable connection with barely understandable platitudes, empty and dull patches, stretched out over such unsparing length as to threaten to run players as well as listeners out of breath.[7]

Here, Hanslick touched on the most common complaint about Bruckner's symphonic writing: the seemingly endless journey to a conclusion of musical thought. Dyneley Hussey critiqued the Sixth Symphony in a 1957 review for The Musical Times and reached the same conclusions half a century later, writing:

His most tiresome habit is his way of pulling up dead at frequent intervals, and then starting the argument all over again...One has the impression...that we are traversing a town with innumerable traffic lights, all of which turn red as we approach them.[48]

Harsh critical reception of the Sixth Symphony, as well as his entire body of work, can also be attributed to critical reception of Bruckner as a person. He was a devout Catholic whose religious fervor often had a negative effect on those he encountered. One of his pupils, Franz Schalk, commented that it was the age of moral and spiritual liberalism...but also in which he [Bruckner] intruded...with his medieval, monasterial concept of humankind and life.[49]

Regardless of the criticisms, both musical and personal, there were some who attempted to find the beauty in Bruckner's Sixth Symphony. Donald Tovey wrote, "...if one clears their mind, not only of prejudice but of wrong points of view, and treats Bruckner's Sixth Symphony as a kind of music we have never heard before, there is no doubt that its high quality will strike us at every moment".[50] Still others marvel over the rarity of performances of the Sixth Symphony, citing its bright character and key and its plethora of tender, memorable themes as grounds for more widespread acceptance.[17]

Carl Hruby wrote that Bruckner once said that if he were to speak to Beethoven about bad critiques Beethoven would say, "My dear Bruckner, don't bother yourself about it. It was no better for me, and the same gentlemen who use me as a stick to beat you with still don't understand my last quartets, however much they may pretend to."[51] In saying this, Bruckner both acknowledged his bad critiques and maintained hope that his own compositions might one day garner the same type of positive reaction that Beethoven's music received from his contemporaries.

Performance and recording history

The first performance of Bruckner's Symphony No. 6 was by the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Wilhelm Jahn on 11 February 1883, making it the only performance of the piece that Bruckner heard in his lifetime. However, only the two middle movements were performed. The first complete performance of the Sixth Symphony occurred in 1899 conducted by Gustav Mahler who made substantial changes to the score. The first full performance of the original score took place in Stuttgart in 1901, conducted by Karl Pohlig.[1] Since that first full performance, the Sixth Symphony has become part of the symphonic repertory, but is the least performed of Bruckner's symphonies, never overcoming its original status as a symphonic "stepchild".[3]

The oldest surviving recorded performance is of Wilhelm Furtwängler conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in 1943; however, the first movement is missing. The oldest surviving complete recorded performance is of Georg Ludwig Jochum with the Bruckner Orchestra Linz from 1944. The first commercial recording is from 1950 and features Henry Swoboda and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra.

Selected discography

- Joseph Keilberth and Berlin Philharmonic 1963 Telefunken

- Otto Klemperer and New Philharmonia Orchestra 2003 EMI Records Ltd (recorded November 1964)

- Eugen Jochum and Symphonie-Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks 1966 Deutsche Grammophon

- William Steinberg and Boston Symphony Orchestra 1972 RCA

- Horst Stein and Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra 1974 Decca

- Daniel Barenboim and Chicago Symphony Orchestra 1977 Deutsche Grammophon

- Herbert von Karajan and Berliner Philharmoniker 1979 Deutsche Grammophon

- Sir Georg Solti and Chicago Symphony Orchestra 1979 Decca

- Wolfgang Sawallisch and Bayerisches Staatsorchester 1982 Orfeo

- Ferdinand Leitner and SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg 1982 Hänssler Classic

- Riccardo Muti and Berliner Philharmoniker 1988 EMI

- Eliahu Inbal and Radio-Sinfonie-Orchester Frankfurt 1989 Teldec

- Herbert Blomstedt and San Francisco Symphony Orchestra 1990 London

- Jesus Lopez-Cobos and Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra 1991 Telarc

- Bernard Haitink and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra 1994 Universal International Music B.V.

- Christoph von Dohnanyi and the Cleveland Orchestra 1994 London

- Gunter Wand and NDR-Sinfonieorchester 1996 RCA Victor

- Eugen Jochum and Staatskapelle Dresden 1998 EMI Records Ltd.

- Sergiu Celibidache and Münchner Philharmoniker 1999 EMI Records, Ltd.

- Riccardo Chailly and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra 1999 Decca

- Christoph Eschenbach and Houston Symphony Orchestra 2000 Koch Int.

- Eugen Jochum and Staatskapelle Dresden 2000 EMI Records Ltd.

- Sir Colin Davis and London Symphony Orchestra 2002 London Symphony Orchestra Ltd.

- Michael Gielen and SWR Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freiburg 2002 Hänssler Classic

- Eugen Jochum and Berliner Philharmoniker 2002 Deutsche Grammophon

- Kurt Masur and Gewandhausorchester Leipzig 2004 BMG Music

- "Alberto Lizzio" and "South German Philharmonic Orchestra" 2005 Point Classics. For details on this dubious attribution, see Alberto Lizzio.

- Kent Nagano and Deutsches-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin 2005 Harmonia Mundi

- Bernard Haitink and Staatskapelle Dresden 2006 Profil

- Andrew Delfs and Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra 2007 Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra

- Roberto Paternostro and Wurttembergische Philharmonie 2007 Bella Musica

- Roger Norrington and Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart des SWR 2008 Hänssler Classic

- Guennadi Rosdhestvenski and USSR Ministry of Culture Symphonic Orchestra 2008 SLG, LLC

- Hans Zanotelli and "Süddeutsche Philharmonie" 2008 SLG, LLC. Note: The "Süddeutsche Philharmonie" is the group referred to above as the "South German Philharmonic", and "Hans Zanotelli" (the name of a real conductor) is another pseudonym used on Alfred Scholz's records (see above).

- Herbert Blomstedt and Gewandhausorchester Leipzig 2009 Questand

- Daniel Barenboim and Staatskapelle Berlin 2014 ACCENTUS Music, ACC202176

- Mariss Jansons and Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra 2015 RCO Live

- Simone Young and Hamburg Philharmonic, 2015 Oehms

Footnotes

- ^ a b c Simpson (1967), p. 124

- ^ Redlich (1963), p. 102.

- ^ a b Korstvedt (2001), p. 185.

- ^ Wolff (1942), pp. 217–218.

- ^ Redlich (1963), p. 95.

- ^ a b c Simpson (1967), p. 150

- ^ a b c d Harrandt (2004), p. 32

- ^ Engel (1955), p. 25.

- ^ Watson (1996), p. 97.

- ^ Hawkshaw & Jackson (2001).

- ^ a b Engel (1955), p. 44

- ^ a b Redlich (1963), pp. 51–52

- ^ Wolff (1942), p. 168.

- ^ Wolff (1942), p. 166.

- ^ Wolff (1942), pp. 163, 166.

- ^ Wolff (1942), pp. 173–174.

- ^ a b Watson (1996), p. 105

- ^ Wolff (1942), p. 172.

- ^ Horton (2004a), p. 138.

- ^ a b Simpson (1967), p. 152

- ^ Engel (1955), pp. 45–46.

- ^ Doernberg (1960), p. 175.

- ^ Engel (1955), p. 49.

- ^ Doernberg (1960), p. 176.

- ^ a b Watson (1996), p. 106

- ^ Simpson (1967), p. 154.

- ^ Korstvedt (2001), p. 193.

- ^ a b Simpson (1967), pp. 156–157

- ^ Doernberg (1960), p. 177.

- ^ Carragan.

- ^ a b Simpson (1967), p. 157

- ^ Korstvedt (2001), p. 195.

- ^ a b Doernberg (1960), p. 178

- ^ a b c d Simpson (1967), p. 160

- ^ Doernberg (1960), p. 179.

- ^ Wolff (1942), p. 222.

- ^ a b Watson (1996), pp. 106–107

- ^ Simpson (1967), p. 161.

- ^ Williamson (2004), p. 90.

- ^ Watson (1996), p. 107.

- ^ Doernberg (1960), p. 181.

- ^ Wolff (1942), p. 225.

- ^ Simpson (1967), pp. 154–155.

- ^ Watson (1996), pp. 107–108.

- ^ Barford (1978), p. 50.

- ^ Simpson (1967), p. 136.

- ^ Simpson (1967), p. 168.

- ^ a b Horton (2004b), p. 5

- ^ Floros (2001), p. 289[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Simpson (1967), p. 123.

- ^ Jackson (2001), p. 207.

References

- Barford, Philip (1978). Bruckner Symphonies. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Carragan, William. "Symphony in D minor – Timing analysis" (PDF).

- Doernberg, Erwin (1960). The Life and Symphonies of Anton Bruckner. New York: Dover Publications.

- Engel, Gabriel (1955). The Symphonies of Anton Bruckner. Iowa City: Athens Press.

- Harrandt, Andrea (2004). "Bruckner in Vienna". In John Williamson (ed.). Cambridge Companion to Bruckner. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–37.

- Hawkshaw, Paul; Jackson, Timothy L. (2001). "Bruckner, (Joseph) Anton". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.40030. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- Horton, Julian (2004a). "Bruckner and the Symphony Orchestra". In John Williamson (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Bruckner. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 138–169.

- Horton, Julian (2004b). Bruckner's Symphonies: Analysis, Reception and Cultural Politics. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Jackson, Timothy L. (2001). "The Adagio of the 6th Symphony and the anticipatory tonic recapitulation in Bruckner, Brahms, and Dvorak". In Crawford Howie; Paul Hawkshaw; Timothy Jackson (eds.). Perspectives on Anton Bruckner. Burlington: Ashgate. pp. 206–227.

- Korstvedt, Benjamin [in French] (2001). "Harmonic daring and symphonic design in the Sixth Symphony: an essay in historical musical analysis". In Crawford Howie; Paul Hawkshaw; Timothy Jackson (eds.). Perspectives on Anton Bruckner. Burlington: Ashgate. pp. 185–105.[clarification needed]

- Redlich, H. F. (1963). Bruckner and Mahler. London: J. M. Dent and Sons.

- Simpson, Robert (1967). The Essence of Bruckner: An Essay towards the Understanding of his Music. London: Victor Gollancz.

- Watson, Derek (1996). Bruckner. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Williamson, John (2004). "The Brucknerian symphony: an overview". In John Williamson (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Bruckner. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–91.

- Wolff, Werner (1942). Anton Bruckner: Rustic Genius. New York: E. P. Dutton.

Further reading

- Anton Bruckner, Sämtliche Werke, Kritische Gesamtausgabe – Band 6: VI. Symphonie A-Dur (Originalfassung), Musikwissenschaftlicher Verlag der internationalen Bruckner-Gesellschaft, Robert Haas (editor), Vienna, 1935

- Anton Bruckner: Sämtliche Werke: Band VI: VI. Symphonie A-Dur 1881, Musikwissenschaftlicher Verlag der Internationalen Bruckner-Gesellschaft, Leopold Nowak (editor), 1952, Vienna

External links

- Bruckner's Symphony No. 6 – Timing analysis by William Carragan

- Symphony No. 6 in A major, Anton Bruckner Critical Complete Edition

- Symphony No. 6: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Bruckner symphony versions by David Griegel

- Complete discography by John Berky

![{ \new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff <<

\set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t \new Voice \tempo "Gemäßigtes Hauptzeitmaß" 2 = 40 \relative e'' {

\clef "treble" \key c \major \stemUp \time 2/2 | % 1

s1 \ff | % 2

r2 \once \override TupletBracket #'stencil = ##f

\times 2/3 {

e8 e8 e8

}

e8\noBeam [e8] }

\relative c'' {

\clef "treble" \key c \major \stemDown \time 2/2 | % 1

c8. ( fis,16 g8. d16

) \once \override TupletBracket #'stencil = ##f

\times 2/3 {

e8 ( g8 b8 )

}

c8\noBeam [-> g8] -> | % 2

c8. ( fis,16 g8. d16 ) \once \override TupletBracket #'stencil = ##f

\times 2/3 {

e8 _( g8 b8 )

}

c8\noBeam r8

} >>

\new Staff \relative c { \set Staff.midiInstrument = #"piano" \key c \major \clef bass \time 2/2

\clef "bass" \key a \major \time 2/2 <c c'>4 ( <g g'>8. <d d'>16 <e

e'>4 ) <c' c'>8 -> <g g'>8 -> | % 2

<c c'>4 ( <g g'>4 <e e'>4 ) r4 }

>> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/e/n/enrcd9st5jkj1r0oujz5a4mshkgjwuc/enrcd9st.png)