The Blue Lamp

| The Blue Lamp | |

|---|---|

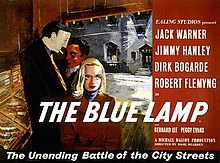

Original UK quad poster by James Boswell | |

| Directed by | Basil Dearden |

| Screenplay by | T.E.B. Clarke |

| Based on | Original treatment by Jan Read and Ted Willis |

| Produced by | Michael Balcon |

| Starring | Jack Warner Jimmy Hanley Dirk Bogarde Robert Flemyng |

| Cinematography | Gordon Dines |

| Edited by | Peter Tanner |

| Music by | Ernest Irving Jack Parnell (uncredited) |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | General Film Distributors |

Release date |

|

Running time | 85 minutes[2] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £142,304[3] |

| Box office | £246,000[4] |

The Blue Lamp is a 1950 British police procedural film directed by Basil Dearden and starring Jack Warner as PC Dixon, Jimmy Hanley as newcomer PC Mitchell, and Dirk Bogarde as criminal Tom Riley.

The title refers to the blue lamps that traditionally hung outside British police stations (and often still do). The film became the inspiration for the 1955–1976 TV series Dixon of Dock Green, where Jack Warner continued to play PC Dixon until he was 80 years old (even though Dixon is murdered in the original film).

The screenplay was written by Ealing regular T. E. B. Clarke, who had been a war reserve constable. The film is an early example of the "social realism" films that emerged later in the 1950s and 1960s, sometimes using a partial documentary-like approach. There are also cinematic influences of the film noir genre, particularly in underworld scenes featuring Bogarde's Tom Riley, such as the pool rooms and in and around the theatre, making deliberate use of genre trademarks like slow moving low camera angles and stark lighting. The plot, however, follows a simple moral structure in which the police are the honest guardians of a decent society, battling the disorganised crime of a few unruly youths. The film was set in London, and partly shot on locations there.

Plot

The action mostly takes place in the Paddington area of west London and is set in July 1949, a few years after the end of the Second World War. PC George Dixon, a long-serving traditional "copper" who is due to retire shortly, supervises a new recruit, Andy Mitchell, introducing him to the night beat.

Dixon is a classic Ealing "ordinary" hero, but also anachronistic, unprepared and unable to answer the violence of Tom Riley. Called to the scene of a robbery at a local cinema, Dixon finds himself face-to-face with Riley, a desperate youth armed with a revolver. Dixon tries to talk Riley into surrendering the weapon, but Riley panics and fires. Dixon dies in hospital some hours later.

On his beat, Mitchell notices a little girl playing with a revolver, which turns out to be the discarded murder weapon. The child is eventually persuaded to lead police to the spot where she found it. Police painstakingly drag a canal and come up with a raincoat that is traced to Diana Lewis' father, who remembers loaning it to Riley.

In his arrogance, Riley goes to Police Headquarters to provide a false alibi for himself. All this accomplishes is to convince the police to place him under 24-hour watch.

Riley is caught with the help of professional criminals and dog-track bookmakers who identify the murderer as he tries to hide in the crowd at White City greyhound track in west London. Credit for arresting Riley falls to young Andy Mitchell.

Cast

- Jack Warner as PC George Dixon

- Jimmy Hanley as PC Andy Mitchell

- Dirk Bogarde as Tom Riley

- Robert Flemyng as Det. Sgt. Roberts

- Bernard Lee as Det. Insp. Cherry

- Peggy Evans as Diana Lewis

- Patric Doonan as Spud

- Bruce Seton as PC Campbell

- Meredith Edwards as PC Hughes

- Clive Morton as Sgt. Brooks

- William Mervyn as Chief Inspector Hammond

- Frederick Piper as Alf Lewis

- Dora Bryan as Maisie

- Gladys Henson as Mrs. Dixon

- Tessie O'Shea as herself

- Sam Kydd as Bookmakers Assistant White City (uncredited)

- Anthony Steel as Police Constable (uncredited)[5]

The ensemble cast also included uncredited actors who later became better known in film, television and radio, including Alma Cogan, Glyn Houston, Jennifer Jayne, Glen Michael, Arthur Mullard, Norman Shelley, Rosemary Nicols (in her film debut as a street urchin) and Campbell Singer.

Production

The character of "Diana" was initially envisioned with Diana Dors in mind, to the extent that the character's name was derived from her own. Nevertheless, the producers harboured reservations about Dors' suitability for the role, citing concerns regarding her emotional maturity. Consequently, a decision was made by the director to pivot away from Dors and opt for a "waif type" persona, leading to the casting of Peggy Evans for the character.[6]

The production had the full co-operation of the Metropolitan Police, and the crew was thus able to use the real-life former Paddington Green Police Station, then at 64 Harrow Road, London W9 and New Scotland Yard for location work. Most of the other outdoor scenes were filmed in inner west London, principally the Harrow Road precincts between Paddington and Westbourne Park. George Dixon is named after producer Michael Balcon's former school in Birmingham.

Locations used

The original blue lamp was transferred to the new Paddington Green Police Station. It is still outside the front of the station and was restored in the early 21st century. Most of the locations around the police station are unrecognisable now due to building of the Marylebone flyover. The police station at 325 Harrow Road, not far from the site of the Coliseum Cinema (324–326 Harrow Road), which is also shown in the film, has a reproduction blue lamp at its entrance.

The Metropolitan Theatre of Varieties, featured prominently at the start of the film, was demolished because it was thought likely that the Marylebone flyover would need the site, although that turned out not to be the case. It is now the site of Paddington Green Police Station. The scene involving a robbery on a jeweller's shop was filmed at the nearby branch of national chain, F. Hinds (then at 290 Edgware Road). This was also knocked down when the flyover was built.

The scenes of the cinema robbery were filmed at the Coliseum Cinema on Harrow Road, next to the Grand Union Canal bridge. The cinema was probably built in 1922, was closed in 1956 and later demolished.[7] The site is now occupied by an office of Paddington Churches Housing Association.

Some of the streets used, or seen, in the film include: Harrow Road W2 and W9, Bishop's Bridge Road W2, Westbourne Terrace Bridge Road W9, Delamere Terrace, Blomfield Road, Formosa Street, Lord Hill's Road, Kinnaird Street and Senior Street W2, Ladbroke Grove W10, Portobello Road W11, Latimer Road, Sterne Street W12 and Hythe Road NW10. The church which features prominently towards the end is St Mary Magdalene, Senior Street W2.[8] Most of the streets around the church were demolished in the 1960s to make way for the new Warwick Estate in Little Venice.

Tom Riley's home was in the run-down street of Amberley Mews, north of the canal, and is now the site of Ellwood Court, part of the Amberley Estate. It is from this mews that Riley walks into Formosa Street, then crosses the Halfpenny Bridge. He then goes into Diana Lewis's flat on the corner of Delamere Terrace and Lord Hill's Road where he attacks her and is chased out by the following detective. Then follows one of the first extended car chases in British film. The route of the chase is as follows: Senior Street W2, Clarendon Crescent W2, Harrow Road W9, Ladbroke Grove W10, Portobello Road W11, Ladbroke Grove W10, Royal Crescent W10, Portland Road W10, Penzance Place W10, Freston Road W10, Hythe Road NW10, Sterne Street W12 – then a chase on foot into Wood Lane and then to White City Stadium.[9] Most of the chase is a logical following of Riley's car apart from when the car goes from Hythe Road NW10 into Sterne Street – Hythe Road in 1949 was a dead end.

Reception

Critical

The Blue Lamp premiered on 20 January 1950 at the Odeon Leicester Square in London,[1] and the reviewer for The Times found the depiction of the police work very plausible and realistic, and praised the performances of Dirk Bogarde and Peggy Evans, but found Jack Warner's and Jimmy Hanley's two policemen portrayed in a too traditional way: "There is an indefinable feel of the theatrical backcloth behind their words and actions ... The sense that the policemen they are acting are not policemen as they really are, but policemen as an indulgent tradition has chosen to think they are, will not be banished."[10]

In the context of a campaign against perceived "middle-class complacency" in British film-making, Sight & Sound editor Gavin Lambert (writing under a pseudonym) attacked the film's "specious brand of mediocrity" and suggested the film was "boring and parochial", views which caused outrage.[11][failed verification]

Writing for The Guardian in 2007, Andrew Pulver called the film "the most successful example of the rough-and-tough Brit crime thriller of the immediate postwar period."[12]

Box-office

The film had the highest audiences in Britain for a British film that year.[13][14] According to Kinematograph Weekly the "biggest winners" at the box office in 1950 Britain were The Blue Lamp, The Happiest Days of Your Life, Annie Get Your Gun, The Wooden Horse, Treasure Island and Odette.[15]

Awards

The film won the 1951 BAFTA Award for Best British Film and was nominated for the Golden Lion at the 1950 Venice Film Festival.[16]

Legacy

In 1951, a stage play of the same name was written by Willis and Read. It ran for 32 performances at the Hippodrome in London. It also played the Hippodrome in Bristol.[17] In 1952, the play ran for 192 performances in a summer season at the Grand Theatre, Blackpool, Lancashire. Gordon Harker took the role of George Dixon, while Jack Warner played Chief Inspector Cherry.[18]

Several of the characters and actors were carried over into the TV series Dixon of Dock Green, including the resurrected Dixon, still played by Warner. The series ran on BBC Television (BBC1) for twenty-one years from 1955 to 1976, with Warner being over eighty by the time of its conclusion.

In 1988, Arthur Ellis's satirical BBC Two play The Black and Blue Lamp had the film characters of Riley (Sean Chapman) and PC "Taffy" Hughes (Karl Johnson) transported forwards in time into an episode of The Filth, a gritty contemporary police television series, replacing their modern-day counterparts.[19]

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier by Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill has one panel suggesting a George Dixon died in August 1898, the time-period given for the first two graphic novels, as well as The War of the Worlds. There is a real George Dixon (1820–98) who was a Victorian politician whom Balcon's school was named after.

In 2010, the BBC Television drama Ashes to Ashes concluded with a short clip of George Dixon, referring to the similarity to Dixon's death in The Blue Lamp and subsequent resurrection for the television series and the underlying plot of the show.[20]

References

- ^ a b The Times, 20 Jan. 1950, page 10: Picture Theatres – Odeon, Leicester Square: The Blue Lamp Linked 2015-04-22

- ^ BBFC: The Blue Lamp - runtime 03/11/1949 Linked 2015-04-22

- ^ Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 356.

- ^ Harper, Sue; Porter, Vincent (2003). British Cinema of The 1950s The Decline of Deference. Oxford University Press USA. p. 281.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (23 September 2020). "The Emasculation of Anthony Steel: A Cold Streak Saga". Filmink.

- ^ Dors, Diana (1960). Swingin' Dors. World Distributors. p. 25.

- ^ "Coliseum Cinema in London, GB - Cinema Treasures". cinematreasures.org.

- ^ Map of W2 locations Archived 30 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine at the Museum of London

- ^ See also Paddington — on film at Greater London Industrial Archaeology

- ^ The Times, 20 Jan. 1950, page 8: Odeon Cinema: "The Blue Lamp" Linked 2015-04-22

- ^ Cited by Geoffrey Macnab in the article "Time for British cinema to rediscover the Aga saga?" at The Independent 2 July 2010. Retrieved 7 January 2015

- ^ The secret artist of Ealing Studios, Andrew Pulver, The Guardian, 5 January 2007

- ^ "Critics Praise Drama: Comedians Win Profits". The Sydney Morning Herald. NSW. 29 December 1950. p. 3. Retrieved 7 January 2015. at Trove

- ^ Thumim, Janet. "The popular cash and culture in the postwar British cinema industry". Screen. Vol. 32, no. 3. p. 258.

- ^ Lant, Antonia (1991). Blackout : reinventing women for wartime British cinema. Princeton University Press. p. 233.

- ^ IMDb: The Blue Lamp (1950) - Awards Linked 2015-04-22

- ^ "Production of The Blue Lamp - Theatricalia". theatricalia.com.

- ^ Wearing, J.P. The London Stage 1950-1959: A Calendar of Productions, Performers, and Personnel. Rowman & Littlefield, 2014 p.198

- ^ "Black and Blue Lamp.qxp" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Simon Brew (21 May 2010). "The significance of the final shot of Ashes to Ashes". Den of Geek. Dennis Publishing. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

External links

- The Blue Lamp at the British Film Institute[better source needed]

- The Blue Lamp at the BFI's Screenonline

- The Blue Lamp at the British Board of Film Classification

- The Blue Lamp at IMDb

- The Blue Lamp location shots at Reelstreets