The Living Daylights (song)

| "The Living Daylights" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

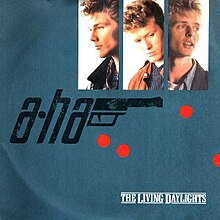

Standard European picture sleeve | ||||

| Single by A-ha | ||||

| from the album The Living Daylights: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack and Stay on These Roads | ||||

| Released | 22 June 1987[1] | |||

| Recorded | 1987 | |||

| Genre | Pop[2] | |||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | Warner Bros. | |||

| Songwriter(s) | ||||

| Producer(s) |

| |||

| A-ha singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| James Bond theme singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Audio sample | ||||

Stay on These Roads version | ||||

"The Living Daylights" is the theme song from the 1987 James Bond film of the same name, performed by Norwegian synth-pop band a-ha. It was written by guitarist Pål Waaktaar. A revised version of the song was included on the band's third studio album, Stay on These Roads (1988).

Origin and recording

John Barry is credited as co-writer and producer, and the initial release of the song was his version. A second version of the song, re-worked by A-ha in 1988, later appeared on their third studio album, Stay on These Roads.

When interviewed on a late-night show in 1987, Barry said that he found working with the band exhausting secondary to the band's insistence on using their own version of the song for release.[3] In an interview with Hot Rod magazine, keyboardist Magne Furuholmen said that "[the band's] fight with Barry left a rather unpleasant aftertaste. Apparently, he compared us to Hitlerjugend in a newspaper interview."[4]

Harket stated in an interview with Paul Lester of The Guardian in 2016 that Barry was "honestly not an easy guy to like. He was very strange in that he started to befriend us by talking bad about Duran Duran. He made some degrading comments about them and what they'd been doing and that didn't sit well with any of us". Harket stated further that; "he then made some derogatory comments about women and it was all uncalled for. There will be people who knew him who will have a very different view of him. But he didn't go down well with us."[5]

In an interview with NME in 2022, Harket commented further that; "It was down to a clash in mentalities. His mentality was the way it was and it surfaced in various ways. None of us agreed with his worldview and the way he spoke about other human beings. We couldn't speak a common language between each other. But his input in the song was essentially just making a few changes to the verse melody: the rest was already there."[6]

Waaktaar stated that although Barry produced the track, he never contributed to the songwriting process and should not have been credited as such.[3] (The band Duran Duran made similar claims after they worked briefly with Barry on the theme to the previous Bond film, "A View to a Kill", in 1985.) The situation grew even more tense when Harket and company informed the producers they would not attend the London premiere. "We fell out with [Bond composer] John Barry, and also the whole Bond Broccoli people [the producers], because we didn't come to the premiere in London. We informed them that, on the date that they had set, we were booked fully in Japan for a big tour. We couldn't make it." The Bond camp assumed A-ha would change their minds. "They didn't think we were serious. And we didn't show up. They went ballistic. They pulled the song from the American version."[7] However, Waaktaar has also said: "I loved the stuff he [John Barry] added to the track. I mean, it gave it this sort of really cool string arrangement. That's when it, for me, started to sound like a Bond thing."[8]

Release and reception

"The Living Daylights" was released in the summer of 1987. The song peaked at number five in the United Kingdom and number one in Norway.

The song remains one of A-ha's most played songs in live concerts and has often been extended into a "sing-along" with the audience, as featured on the live album How Can I Sleep with Your Voice in My Head. In live performances, Waaktaar often included the main James Bond Theme in his guitar solo.[citation needed]

Evan Cater of AllMusic said the song was "a strong sample of Seven and the Ragged Tiger-influenced Europop, enhanced by Morten Harket's powerhouse falsetto vocals."[9]

South African heavy metal band The Narrow released a cover version in 2005.[10]

Music video

The music video, which was directed by Steve Barron, was shot at the 007 Stage in London, which was built specifically for the James Bond franchise.[3] It features various scenes from the film projected on to the band as they perform in the empty 007 Stage. Separate footage from the movie itself is shown, along with footage from the film traced out and inserted to the footage of the band performing, which was a groundbreaking, yet expensive innovation at that time.

Track listings

7-inch single: Warner Bros. / W 8305 United Kingdom

- "The Living Daylights" – 4:04

- "The Living Daylights" (instrumental) – 4:36

12-inch single: Warner Bros. / W 8305T United Kingdom

- "The Living Daylights" (extended mix) – 6:48

- "The Living Daylights" (7-inch version) – 4:04

- "The Living Daylights" (instrumental) – 4:36

- Track 1 is also known as the "extended version".

- Also released as a 12" picture disc (W 8305TP)

Charts

Alternative rejected theme song

Like other Bond themes before it, A-ha's release was not the only recorded song for the film. English synth-pop band Pet Shop Boys also recorded a song for the film that was optioned to the studio. The duo later reworked the song they submitted into "This Must Be the Place I Waited Years to Leave", which was released on their Behaviour album in 1990.

MTV Unplugged appearance

In 2017, A-ha appeared on the television series MTV Unplugged and played and recorded acoustic versions of many of their popular songs for the album MTV Unplugged – Summer Solstice in Giske, Norway, including "The Living Daylights".[36]

See also

References

- ^ Strickland, Andy (20 June 1987). "News Digest". Record Mirror. p. 17. ISSN 0144-5804.

- ^ Ehrlich, David (2 November 2015). "James Bond Movie Theme Songs, Ranked Worst to Best". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 27 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "The Official Community of A-ha". A-ha.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ "Interview for Hotrod Magazine with Magne Furuholmen" (PDF). magnef.org. February 2003. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- ^ "A-ha's Morten Harket: 'I'm not an entertainer, I'm an engager'". TheGuardian.com. 4 May 2016.

- ^ "A-ha: "I knew 'The Masked Singer' would be shitty"". NME. 2 September 2022.

- ^ "Morten Harket of A-ha: 'We were jealous of U2. They didn't get that Smash Hits-type fame'". The Irish Times.

- ^ "a-ha v John Barry Good Friends REALLY". Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2014 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Allmusic review of The Living Daylights soundtrack album". Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Trenton, Curt (29 March 2014). "The Narrow The Living Daylights Mp3 Download". www.asongz.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 13. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "a-ha – The Living Daylights" (in German). Ö3 Austria Top 40. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ "a-ha – The Living Daylights" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 0875." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Top 3 in Europe". Music & Media. Vol. 4, no. 33. 22 August 1987. p. 16. OCLC 29800226.

- ^ "European Hot 100 Singles". Music & Media. Vol. 4, no. 34. 29 August 1987. p. 12. OCLC 29800226.

- ^ Pennanen, Timo (2021). "A-ha". Sisältää hitin – Levyt ja esittäjät Suomen musiikkilistoilla 1.1.1960–30.6.2021 (PDF) (in Finnish) (2nd ed.). Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava. p. 11. ISBN 978-952-7460-01-6.

- ^ "a-ha – The Living Daylights" (in French). Les classement single. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ "The Irish Charts – Search Results – The Living Daylights". Irish Singles Chart. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Top 3 in Europe". Music & Media. Vol. 4, no. 34. 29 August 1987. p. 14. OCLC 29800226.

- ^ "Nederlandse Top 40 – a-ha" (in Dutch). Dutch Top 40. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "a-ha – The Living Daylights" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "a-ha – The Living Daylights". Top 40 Singles. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "a-ha – The Living Daylights". VG-lista. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ "SA Charts 1965–1989 (As presented on Springbok Radio/Radio Orion) – Acts A". The South African Rock Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ Salaverrie, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (in Spanish) (1st ed.). Madrid: Fundación Autor/SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "a-ha – The Living Daylights". Singles Top 100. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ "a-ha – The Living Daylights". Swiss Singles Chart. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "a-ha: Artist Chart History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – a-ha – The Living Daylights" (in German). GfK Entertainment charts. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten 1987 – Singles" (in Dutch). Ultratop. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Top Sellers 1987". Music & Media. Vol. 5, no. 11. 12 March 1988. p. 25. OCLC 29800226.

- ^ "European Charts of the Year 1987 – Singles". Music & Media. Vol. 4, no. 51/52. 26 December 1987. p. 34. OCLC 29800226.

- ^ "Jaaroverzichten – Single 1987" (in Dutch). Dutch Charts. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Top 100 Single-Jahrescharts – 1987" (in German). GfK Entertainment. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- ^ Hoftun Gjestad, Robert (23 June 2017). "Etter 30 år med "tension" fant a-ha tonen igjen i kampen mot en felles fiende" [After 30 years of "tension", A-ha found their sound again, in their fight against a common enemy]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian Bokmål).