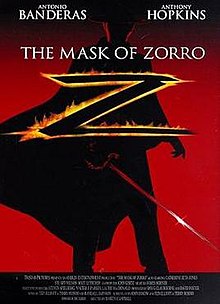

The Mask of Zorro

| The Mask of Zorro | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Martin Campbell |

| Screenplay by | John Eskow Ted Elliott Terry Rossio |

| Story by | Ted Elliott Terry Rossio Randall Jahnson |

| Based on | Zorro by Johnston McCulley |

| Produced by | Doug Claybourne David Foster |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Phil Méheux |

| Edited by | Thom Noble |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | TriStar Pictures[1][2] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 137 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $95 million |

| Box office | $250.3 million |

The Mask of Zorro is a 1998 American Western swashbuckler film based on the fictional character Zorro by Johnston McCulley. It was directed by Martin Campbell and stars Antonio Banderas, Anthony Hopkins, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and Stuart Wilson. The film features the original Zorro, Don Diego de la Vega (Hopkins), escaping from prison to find his long-lost daughter (Zeta-Jones) and avenge the death of his wife at the hands of the corrupt governor Rafael Montero (Wilson). He is aided by his successor (Banderas), who is pursuing his own vendetta against the governor's right-hand man while falling in love with de la Vega's daughter.

Executive producer Steven Spielberg had initially developed the film for TriStar Pictures with directors Mikael Salomon and Robert Rodriguez, before Campbell signed on in 1996. Salomon cast Sean Connery as Don Diego de la Vega, while Rodriguez brought Banderas in the lead role. Connery dropped out and was replaced with Hopkins, and The Mask of Zorro began filming in January 1997 at Estudios Churubusco in Mexico City, Mexico.

The film was released in the United States on July 17, 1998 to critical and commercial success, grossing $250 million on a $95 million budget. The film was nominated for two Academy Awards and two Golden Globe Awards.

The Legend of Zorro, a sequel also starring Banderas and Zeta-Jones and directed by Campbell, was released in 2005, but did not fare as well as its predecessor.[3]

Plot

In 1821, masked swordsman Zorro defends the commoners of Las Californias from Spain's soldiers. Don Rafael Montero, Las Californias' corrupt governor, sets a trap for Zorro at the public execution of three peasants. Zorro stops the execution, and Montero's soldiers are thwarted by two young brothers, Alejandro and Joaquín Murrieta. Zorro fights the remaining soldiers and thanks the brothers by giving Joaquín a medallion.

Don Montero deduces Spanish-born nobleman Don Diego de la Vega is Zorro and attempts to arrest him at his home. A swordfight begins, a fire breaks out, and de la Vega's wife Esperanza, whom Montero covets, is murdered in the process. While the building burns, Montero takes Diego's infant daughter, Elena, as his own before sending de la Vega to prison and returning to Spain.

In 1841, Alejandro and Joaquín are bandits, running a scam to collect the bounty on their heads and steal a strongbox. They, however, fail and are caught by Captain Harrison Love, Montero's new American right-hand man. Alejandro escapes, while Joaquín shoots himself to avoid execution by Captain Love. Meanwhile, Montero returns to California with the now adult Elena. Because of Montero, Elena believes her mother died in childbirth.

Montero's reappearance motivates de la Vega to escape captivity. He encounters a drunk Alejandro and recognizes the medallion he gave his brother. He agrees to make Alejandro his protégé in order for them to take revenge on their respective enemies, Montero and Love. Alejandro agrees to undergo de la Vega's intense training in Zorro's secret lair underneath the ruins of his family estate. In addition, Alejandro seeks to succeed de la Vega as Zorro.

While still being trained, Alejandro steals a stallion resembling Zorro's steed Tornado from the local garrison, masked like "Zorro" and barely escaping. De la Vega scolds Alejandro, asserting that Zorro was a servant of the people, not a thief. He challenges Alejandro to gain Montero's trust instead.

Alejandro poses as a visiting nobleman named Don Alejandro del Castillo y García, with de la Vega as his servant "Bernardo", and attends a party at Montero's hacienda. There, he earns Elena's admiration and enough of Montero's trust to be invited to a secret meeting between noblemen. Montero hints at a plan to retake California for the Dons and proclaim it as an independent republic by buying it from General Santa Anna, who needs money for the upcoming Mexican–American War.

Montero takes Alejandro and the noblemen to a secret gold mine where peasants and prisoners are used for slave labor. He plans to buy California from Santa Anna using gold mined from his own land. While walking in a market, Elena meets the woman who was her nanny. She tells Elena her parents' real identity.

De la Vega sends Alejandro, now Zorro, to steal Montero's map leading to the gold mine. Zorro duels Montero, Love, and their guards at the hacienda. When he escapes, Elena chases him, attempting to retrieve Montero's map. After a sword duel, Zorro kisses her and flees.

Fearing Santa Anna's retribution, Montero decides to destroy the mine and kill the workers to leave no witnesses. De la Vega tells Alejandro to release the workers on his own so he can reclaim Elena. Alejandro sets off, feeling betrayed by Diego's vendetta. De la Vega corners Montero at the hacienda and reveals his identity, before Montero captures him.

While being taken away, de la Vega tells Elena the name of the flowers she recognized upon her arrival in California, convincing her that he is her father. She releases de la Vega from his cell. They proceed to the mine, where Alejandro and de la Vega duel and slay Love and Montero respectively. Elena and Alejandro free the workers before the explosives go off and find the mortally wounded de la Vega. Before dying, he makes peace with the pair and gives his blessings for Alejandro to continue as Zorro and be with Elena.

Sometime later, Alejandro and Elena are married with an infant son "Joaquín", to whom Alejandro tells of the deeds of Zorro.

Cast

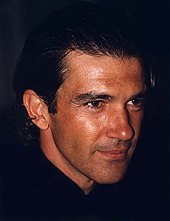

- Antonio Banderas as Alejandro Murrieta / Zorro:

Banderas was paid $5 million for the role. The character of Alejandro Murrieta was conceived as the fictional brother of the real-life Joaquin Murrieta, making the character either Mexican or Chilean.[4] To prepare for his role, Banderas practiced with the Olympic fencing team in Spain for four months, before studying additional fencing and swordsmanship with Anthony Hopkins and Catherine Zeta-Jones.[5] The three were trained by Bob Anderson during pre-production in Mexico, spending 10 hours a day for two months specifically on fight scenes from the film.[6] "We used to call him Grumpy Bob on the set, he was such a perfectionist," director Martin Campbell reflected. "He was incredibly inventive, and also refused to treat any of the actors as stars. They would complain about the intensity of the training, but having worked with him there's nobody I'd rather use."[7] During interviews for The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, Anderson rated Banderas the best natural talent he had worked with. Before Banderas was chosen for the role, Benicio Del Toro, Andy García, Marc Anthony, Joaquim de Almeida, and Chayanne were considered.[8][9]- José María de Tavira portrays a young Alejandro Murrieta.

- Anthony Hopkins as Don Diego de la Vega / Zorro:

Hopkins was cast in December 1996, one month before filming began.[10] Hopkins, known for his dramatic acting, took up the role because of his enthusiasm to be in an action film.[11] For the role of Diego de la Vega, actors Sean Connery and Raúl Juliá, who died before he could take the role, were also considered.[12][13] - Catherine Zeta-Jones as Elena Montero:

The actress signed on in November 1996, when Spielberg saw her performance in the Titanic miniseries and recommended her to Campbell.[14] Despite being a Welsh actress portraying a Spanish character, Zeta-Jones discovered similarities between her "volatile" Celtic temper and the Latin temperament of Eléna.[15] Izabella Scorupco, who worked with Campbell on GoldenEye, Judith Godrèche, Salma Hayek, Shakira and Jennifer Lopez screen tested for the part.[16][8][17][14] Zeta-Jones credits The Mask of Zorro as her breakthrough in entering A-list recognition.[15][18]- María and Mónica Fernández Cruz portray Elena de la Vega (infant).

- Stuart Wilson as Don Rafael Montero:

Armand Assante had initially been cast in the role, but dropped out due to scheduling conflicts with The Odyssey.[19] Stuart Wilson, who Campbell previously directed in No Escape, was cast in Assante's place four months after.[20] Actors Sam Shepard, Lance Henriksen, Edward James Olmos, Scott Glenn and Giancarlo Giannini were also considered for the role.[citation needed] - Matt Letscher as Captain Harrison Love

- Tony Amendola as Don Luiz

- Pedro Armendáriz Jr. as Don Pedro

- Victor Rivers as Joaquin Murrieta

- Diego Sieres as young Joaquín

- L. Q. Jones as Three-Fingered Jack: Alejandro and Joaquin's partner, captured and later killed by Harrison Love at the mine.

- Julieta Rosen as Esperanza De La Vega: Don Diego's beloved wife and Elena's mother

Other actors in the film include William Marquez as Fray Felipe, Maury Chaykin as a prison warden, Jose Perez as the bumbling Corporal Garcia (a character originating in the 1950s American TV series), Humberto Elizondo as Don Julio, Fernando Becerril as Don Sergio, and Vanessa Bauche as an Indio girl. Joaquim de Almeida filmed scenes as Antonio López de Santa Anna, but his role was cut from the final film.

Production

Development

In October 1992, TriStar Pictures and Steven Spielberg's Amblin Entertainment were planning to start production on Zorro the following year, and hired Joel Gross to rewrite the script after they were impressed with his adaptation of The Three Musketeers.[21][22] At the time, Spielberg was producing Zorro with the potential to direct.[23] Gross completed his rewrite in March 1993, and TriStar entered pre-production, creating early promotion for the film that same month at the ShoWest trade show.[24][25] By December 1993, Branko Lustig was producing the film with Spielberg, and Mikael Salomon was attached as director.[26] In August 1994, Sean Connery was cast as Don Diego de la Vega, while Salomon stated that the rest of the major cast would be Hispanic or Latino. The first chosen for the role of Zorro in his young version was Andy García, a fashionable Latin actor at the time.[27] The role of Zorro was offered to Tom Cruise, but he declined as he felt it wasn't a good idea.[28] Colombian singer Shakira was also initially considered to play Elena but turned it down due to her limited acting experience (despite having co-starred in the Colombian TV series El Oasis) and her own poor English skills at the time.[29] Pre-production proceeded even further in August when Salomon compiled test footage for a planned April 1995 start date.[30] Viggo Mortensen read for a role as a sheriff.[28]

Connery and Salomon eventually dropped out, and in September 1995, Robert Rodriguez, fresh off the success of Desperado, signed to direct with Antonio Banderas, who had also starred in Desperado, playing the title role.[31] TriStar and Amblin had been surprised by Rodriguez's low-budget filming techniques for his action films, El Mariachi and Desperado, and shifted away from their initial plans with Salomon to make a big-budget version of Zorro.[32] Spielberg had hoped Rodriguez would start filming in January 1996 for a Christmas release date, but the start date was pushed back to July.[33][34][35] The release date was later moved to Easter 1997.[36] Rodriguez pulled out of the film in June 1996 over difficulties coming to terms with TriStar on the budget. The studio projected a range of $35 million, while Rodriguez wanted $45 million. They both attempted to compromise when Rodriguez lowered it to $42 million, but the studio refused and set $41 million as their highest mark.[36] Banderas remained with the production, and Martin Campbell signed on later that month, turning down the chance to direct Tomorrow Never Dies.[37] The finished screenplay would be written by John Eskow, Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, based on a story by Elliott, Rossio, and Randall Jahnson.[38]

Filming

The principal photography for the film began in Mexico on January 27, 1997 on a $60 million (~$106 million in 2023) budget.[6][20] The Mask of Zorro was mostly shot at Estudios Churubusco in Mexico City.[39] Production stalled for four days in February when the director, Martin Campbell, was hospitalized for bronchitis. Filming resumed in Tlaxcala, three hours east of Mexico City, where the production crew constructed the Montero hacienda and town set pieces.[40] Sony sent David Foster to join the project as a producer to help fill the void left by Steven Spielberg, Walter F. Parkes, and Laurie MacDonald, who were busy running DreamWorks. Foster and David S. Ward, who went uncredited, re-wrote some scenes;[41] the troubled production caused The Mask of Zorro to go $10 million over its budget.[41][42] In December, the producers were frustrated by customs agents when some props and other items, including Zorro's plastic sword, were held for nine days.[39] Rossio and Elliott originally planned to have Don Rafael Montero be introduced by arriving on shore in a boat while sitting on a horse standing in the boat, but the scene was cut for being deemed too expensive. The idea was ultimately revisited by the duo for Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest.[43] During the post-production phase, Spielberg and Campbell decided that Diego de la Vega's death in the arms of his daughter was too depressing.[44] The ending, where Alejandro and Eléna are happily married with their infant son, was added three months after filming had ended.[45]

Lawsuit

On January 24, 2001, Sony Pictures Entertainment filed a lawsuit in United States District Court, Central District of California, Western Division, against Fireworks Entertainment Group, the producers of the syndicated television series Queen of Swords. Sony alleged copyright infringement and other claims, saying the series "copied protectable elements from [the] 'Zorro' character and 'Zorro' related works". On April 5, 2001, U.S. District Judge Collins denied Sony's motion for a preliminary injunction, noting "that since the copyrights in [Johnson McCulley's 1919 short story] The Curse of Capistrano and [the 1920 movie] The Mark of Zorro lapsed in 1995 or before, the character Zorro has been in the public domain." As to specific elements of The Mask of Zorro, the judge found that any similarities between the film and the TV series' secondary characters and plot elements were insufficient to warrant an injunction.[46]

Soundtrack

| The Mask of Zorro: Music from the Motion Picture | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | ||||

| Released | July 7, 1998 | |||

| Recorded | 1997–1998 | |||

| Genre | Soundtrack | |||

| Length | 74:47 | |||

| Label | Sony Classical Records Epic Soundtrax | |||

| Producer | Jim Steinman Simon Rhodes Tony Hinnigan James Horner | |||

| James Horner soundtracks chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Mask of Zorro: Music from the Motion Picture | ||||

| ||||

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Empire | |

| Filmtracks | |

| SoundtrackNet | |

James Horner was hired to compose the film score in September 1997.[47] The soundtrack, released by Sony Classical Records and Epic Soundtrax, was commercially successful and propelled by the rising profile of the Latin heartthrobs of Marc Anthony and Australian singer Tina Arena. Their duet, "I Want to Spend My Lifetime Loving You", plays in the closing credits of the film and was released as a single in Europe.[48] The song went #3 on the French singles and #4 on the Dutch singles charts.[49][50] At the 1999 ALMA Awards, it won Outstanding Performance of a Song for a Feature Film.[51]

Historical references

The Mask of Zorro and its sequel The Legend of Zorro incorporate certain historical events and people into their narrative. Antonio Banderas' character, Alejandro Murrieta, is a fictional brother of Joaquin Murrieta, a real Mexican outlaw who was killed by the California Rangers led by Harry Love (portrayed in the film as Texas Army Captain "Harrison Love") in 1853. The confrontation in the film takes place more than a decade earlier, in 1841. The capture of Murrieta's right-hand man Three-Fingered Jack by Love was also historical; however, the real person was a Mexican named Manuel Garcia rather than an Anglo-American.[52] As he did in the movie, the actual Harry Love preserved both Murrieta's head and Jack's hand in large, alcohol-filled glass jars.[53]

Release

The Mask of Zorro was initially set for release on December 19, 1997 before the release date was changed to March 1998.[54] There was speculation within the media about whether TriStar changed the date in an attempt to avoid competition with Titanic. In reality Zorro had encountered production problems that extended its shooting schedule. In addition, Sony Pictures Entertainment, TriStar's parent company, wanted an action film for its first quarter releases of 1998.[42] The release date was once again pushed back, this time to July 1998, when pick-ups were commissioned.[55] The delay from March to July added $3 million in interest costs.[56]

To market The Mask of Zorro, TriStar purchased a 30-second advertising spot at Super Bowl XXXII for $1.3 million.[56] Sony, who had been known for their low-key presence at the ShoWest trade show, showed clips from the film, while actors Antonio Banderas and Anthony Hopkins presented a panel at the conference on May 10, 1998.[57] The studio also attached the film's trailer to prints of Godzilla.[58] Sony launched an official website in June 1998. Internet marketing was an emerging concept in the late-1990s, and Zorro was Sony's first film to use VRML.[59]

The Mask of Zorro caught the attention of European Royalty with the film's foreign premieres. Spain's King Juan Carlos I, Queen Sophia, and Princess Elena attended the first Royal premiere in Madrid in seven years. On December 10, 1998, a Royal Command Performance for Zorro was toplined by Prince Charles and his sons.[60]

Home media

The Mask of Zorro was released on VHS and DVD on December 1, 1998 by Columbia TriStar Home Video. The film was released on Blu-ray on December 1, 2009 by Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, and in 4K UHD on May 5, 2020.[61]

Reception

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes, The Mask of Zorro has an approval score of 84% based on 79 reviews with an average score of 7.1/10. The site's consensus states: "Banderas returns as an aging Zorro in this surprisingly nimble, entertaining swashbuckler."[62] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 63 based on reviews from 22 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[63] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A−" on an A+ to F scale.[64]

Richard Schickel of Time magazine praised The Mask of Zorro as a summer blockbuster which paid tribute to the classical Hollywood swashbuckler films. "The action in this movie, most of which takes the form of spectacular stunt work performed by real, as opposed to digitized, people," Schickel stated, "is motivated by simple, powerful emotions of an old-fashioned and rather melodramatic nature."[65] Zorro exceeded the expectations of Roger Ebert, who was surprised by the screenplay's display of traditional film craftsmanship. "It's a reminder of the time when stunts and special effects were integrated into stories, rather than the other way around."[66] Ebert gave the film three out of four stars, and would later call it "probably the best Zorro movie ever made."[3] Mick LaSalle, writing in the San Francisco Chronicle gave credit to Anthony Hopkins for his masculine portrayal of an older Zorro, adding that the actor's "performance presents a slight problem: The film asks us to believe that no one has figured out that Zorro and his real-life persona are the same person, even though they are the only guys in Mexico who talk with a British accent."[67]

Todd McCarthy of Variety found the film's length to be "somewhat overlong" and lacking "the snap and concision that would have put it over the top as a bang-up entertainment, but it's closer in spirit to a vintage Errol Flynn or Tyrone Power swashbuckler than anything that's come out of Hollywood in quite some time."[68] In his review for Rolling Stone magazine, Peter Travers criticized the casting choices for the Mexican roles, which included Banderas, a Spaniard, as well as Hopkins and Zeta-Jones, who are both Welsh. Disappointed with the film's entertainment value, Travers also expected the film to be a failure with audiences.[69] Internet reviewer James Berardinelli compared the tone and style of The Mask of Zorro to producer Steven Spielberg's Raiders of the Lost Ark. "While The Mask of Zorro isn't on the same level, it's not an altogether ridiculous comparison. Even though Zorro doesn't feature the non-stop cliffhanger adventure of Raiders," Berardinelli continued, "there's still plenty of action, tumult, and derring-do." He was undecided whether the film would be a box office success, and that it would depend on the on-screen chemistry between Banderas and Zeta-Jones.[70]

In one of the film's most popular scenes, Alejandro renders Eléna topless with a flurry of sword slashes. One critic placed it on his list of "Erotic [Film] Scenes in the 90s".[71]

Box office

The Mask of Zorro was released in the United States on July 17, 1998 in 2,515 theaters, earning $22,525,855 (~$39.3 million in 2023) in its opening weekend.[72][73] The film dropped from its number one position in the second week with the releases of Saving Private Ryan and There's Something About Mary.[74] The Mask of Zorro eventually earned $94,095,523 within the United States, and $156,193,000 internationally, coming to a worldwide total of $250,288,523.[73] With the commercial success of the film, Sony sold the television rights of The Mask of Zorro for $30 million in a joint deal to CBS and Turner Broadcasting System.[75]

Accolades

| Awarding Body | Award | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[76][77] | Best Sound | Kevin O'Connell, Greg P. Russell, and Pud Cusack | Nominated |

| Best Sound Effects Editing | Dave McMoyler | Nominated | |

| British Academy Film Awards (BAFTAs)[78] | Best Costume Design | Graciela Mazón | Nominated |

| Golden Globe Awards[79] | Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Nominated | |

| Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy | Antonio Banderas | Nominated | |

| MTV Movie Awards[80] | Best Breakthrough Female Performance | Catherine Zeta-Jones | Nominated |

| Best Fight | Antonio Banderas, Catherine Zeta-Jones | Nominated | |

| Saturn Awards[81] | Best Action/Adventure/Thriller Film | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Catherine Zeta-Jones | Nominated | |

| Best Costumes | Graciela Mazón | Nominated |

Comic book adaptation

- Image Comics: The Mask of Zorro (August 1998)[82]

References

- ^ "AFI Catalog - The Mask of Zorro". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 14, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (July 17, 1998). "'The Mask of Zorro': The Cunning Fox Is Back". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 14, 2024. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (October 28, 2005). "The Legend of Zorro". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 28, 2005. Retrieved October 25, 2022.

probably the best Zorro movie ever made, although having not seen them all I can only speculate.

- ^ Longsdorf, Amy (July 11, 1998). "Spotlight on Antonio Banderas". The Morning Call.

- ^ Masterson, Lawrie (August 2, 1998). "Q and A with Antonio Banderas". Sunday Mirror.

- ^ a b Archerd, Army (December 9, 1996). "Douglases save coastal land". Variety. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Cohen, Richard (December 29, 2001). "En Garde! The Master Who Puts the Swords in the Hands of the Stars". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "1 anécdotas y secretos de rodaje sobre la máscara del Zorro".

- ^ "Chayanne: La vez que perdió el papel de el Zorro ante Antonio Banderas | Historia | Celebs | FAMA". September 24, 2021.

- ^ Archerd, Army (December 8, 1996). "Happy Birthday to Kirk Douglas". Variety. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Wolk, Josh (July 17, 1997). "Anthony Hopkins gets active in 'The Mask of Zorro'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 16, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ "The Mask of Zorro - Trivia".

- ^ "The Mask of Zorro: 20 Facts About the Film That Will Really Leave a Mark". October 11, 2019.

- ^ a b Sterngold, James (May 10, 1998). "Makeover Time for a Once and Would-Be Star". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Marin, Rick (May 2, 1999). "Zorro's Girl Outgrows Her Petticoats". The New York Times.

- ^ "7 interesting facts about 'The Mask of Zorro' - Movie'n'co".

- ^ "Shakira, Muy Cerca de el Zorro". June 6, 1996.

- ^ Fierman, Daniel (August 14, 1998). "The Devil In Miss Zeta-Jones". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 4, 2009. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Archerd, Army (August 14, 1996). "Assante may not carve out his 'Z'". Variety. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ a b Cox, Dan (December 12, 1996). "Wilson's taking up the sword for ' Zorro'". Variety. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Frook, John Evan (October 14, 1992). "TriStar Pix kicks off 'Rudy' film". Variety. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Frook, John Evan (November 23, 1992). "'Musketeers' vs. Mouseketeers". Variety. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Eller, Claudia (February 1, 1993). "Nicholson, Nolte, Mancuso team". Variety. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Frook, John Evan (February 4, 1993). "TriStar slate reflects '93 about-'Face'". Variety. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Frook, John Evan (March 10, 1993). "TriStar slate stellar at NATO". Variety. Retrieved January 4, 2011.

- ^ Frook, John Evan (December 9, 1993). "TriStar develops full dance card for '94-95". Variety. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Valenzuela, Javier (July 17, 1998). "'La máscara del Zorro' consagra a Antonio Banderas como una gran estrella en EE UU". El País.

- ^ a b "The Mask of Zorro at 25: An Oral History of the Last Old School Blockbuster". December 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Mask of Zorro (1998) - IMDb". IMDb.

- ^ Archerd, Army (August 4, 1994). "Sean Connery, As Diego De La Vega". Variety. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Eller, Claudia (September 22, 1995). "Sony Learns to Schmooze Wall Street". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "'Desperado' Team Reunited". Los Angeles Daily News. December 17, 1995.

- ^ Bart, Peter (October 29, 1995). "DreamWorks revving up its filmmaking engine". Variety. Retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Arnold, William (January 10, 1996). "1996 should be a hot year for film". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ^ Danini, Carmina (November 17, 1995). "Rodriguez has eye on S.A., Austin area for two new movies". San Antonio Express-News.

- ^ a b "Budget Dispute Hangs Up 'Zorro'". San Jose Mercury News. June 13, 1996.

- ^ Dawtrey, Adam & Rex Weiner (December 30, 1996). "MGM's Completion Bond". Variety. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ Wolf, James (August 23, 1998). "The Blockbuster Script Factory". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Muttalib, Bashirah (January 16, 1998). "Rediscovering Mexico". Variety. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Archerd, Army (February 18, 1997). "Flu fells 'Zorro' director". Variety. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Cox, Dan (March 20, 1997). "Inside Moves". Variety. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Klady, Leonard (May 27, 1997). "TriStar moves 'Zorro' to '98". Variety. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "Wordplayer.com: WORDPLAY/Archives/"Caribbean Tales - 2005" by Terry Rossio". July 6, 2005. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Archerd, Army (January 8, 1998). "'Zorro' ending to stay". Variety. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Archerd, Army (July 13, 1998). "Berle tribute gets emotional". Variety. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ "Sony Pictures Entertainment v. Fireworks Enter."

- ^ Archerd, Army (September 25, 1997). "Sinatra family goes online". Variety. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Sandler, Adam (July 30, 1998). "Beastie Boys still 'Nasty'". Variety. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ "'I Want to Spend My Lifetime Loving You' (in French)". Lescharts.com. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ "Dutch Charts - End Of Year Charts - Top 100 Singles 1999 (written in Dutch)" (PDF). Nederlandse Top 40. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ "23rd Anniversary of 'I Want To Spend My Lifetime Loving You' by Tina Arena & Marc Anthony". We Miss Music. October 9, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ^ Valdez, Luis (July 1998). "The Face of Zorro". Salon. Retrieved October 7, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ Gumbel, Andrew (October 25, 2005). "What the legend of Zorro tells us about the history of America". The Independent. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- ^ Busch, Anita M. (May 27, 1997). "'Titanic' on ice until Dec. in U.S., o'seas". Variety. Retrieved October 23, 2010.

- ^ "Reel World: This Week In Hollywood". Entertainment Weekly. October 31, 1997. Archived from the original on December 16, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ a b Archerd, Army (September 23, 1997). "'Zorro' buys $1.3 mil Super Bowl ad". Variety. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Cox, Dan & Michael Fleming (May 10, 1998). "Sony offers exhibs stars and hip clips". Variety. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Hindes, Andrew (October 2, 1997). "Sony parry thrusts 'Zorro' into summer". Variety. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ "Meeting expectations of a Web-centric world". Variety. May 20, 1998. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Archerfd, Army (November 10, 1998). "Spielberg to give 'unflinching' look at Lindbergh". Variety. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ The Mask of Zorro 4K Blu-ray, retrieved May 27, 2020

- ^ "The Mask of Zorro". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ "The Mask of Zorro". Metacritic. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ EW Staff (August 7, 1998). "Critical Mass". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (July 20, 1998). "Cinema: The Mark of Excitement". Time. Archived from the original on January 29, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 17, 1998). "The Mask of Zorro". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on April 5, 2005. Retrieved October 25, 2010 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (July 17, 1998). "Zzzzzz-orro: Entertaining swashbuckler a cut below exciting". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved October 25, 2010.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (June 25, 1998). "The Mask of Zorro". Variety. Retrieved October 25, 2010.

- ^ Travers, Peter (July 17, 1998). "The Mask of Zorro". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 31, 2005. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (January 1, 2000). "The Mask of Zorro". Reel Views. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ Dirks, Tim. "Great Moments and Scenes from the Greatest Films". Filmsite.org. Archived from the original on April 16, 2008. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ Fleeman, Michael (July 21, 1998). "Despite hits, summer lacks a real blockbuster". The Associated Press. Daily Record. p. 19. Archived from the original on October 23, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "The Mask of Zorro". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ "Weekly Box Office: July 24-30, 1998". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ Littleton, Cynthia (July 27, 1998). "Eye web, Turner cut $30 mil 'Zorro' pact". Variety. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ "The 71st Academy Awards (1999) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ "71st Academy Awards". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved October 26, 2010. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Mask of Zorro". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ "The Mask of Zorro". Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on July 13, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ "1999 MTV Movie Awards". MTV Movie Awards. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ "Past Award Winners". Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films. Archived from the original on May 12, 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2010.

- ^ Image Comics: The Mask of Zorro at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)