Theotokos of the Pharos

The Church of the Virgin of the Pharos (Greek: Θεοτόκος τοῦ Φάρου, Theotokos tou Pharou) was a Byzantine chapel built in the southern part of the Great Palace of Constantinople, and named after the tower of the lighthouse (pharos) that stood next to it.[1] It housed one of the most important collections of Christian relics in the city, and functioned as the chief palatine chapel of the Byzantine emperors.

History

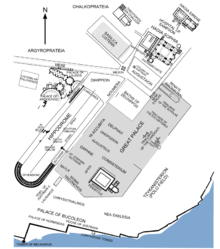

The church was probably built sometime in the 8th century, as it is first attested in the chronicle of Theophanes the Confessor for 769: it was there that the future emperor Leo IV (r. 775–780) married Irene of Athens.[2] Emperor Leo V (r. 813–820) was assassinated there.[3] The church was located close to the ceremonial heart of the palace, the throne room of the Chrysotriklinos and the adjoining imperial apartments.[4] Following the end of iconoclasm, it was extensively rebuilt and redecorated by Emperor Michael III (r. 842–867).[2] As restored, it was a relatively small building with a ribbed dome, three apses, a narthex and a "splendidly fashioned" atrium.[5] On the occasion of its rededication, probably in 864, the Patriarch Photios held one of his most famous homilies lauding the church's spectacular decoration.[2][6] Indeed, Photios takes the unusual step of criticizing the church, albeit subtly, for being too sumptuous, especially given its small size.[7]

Together with the churches of St Stephen in the Daphne Palace and the Nea Ekklesia, the Virgin of the Pharos came to hold one of the major collections of Christian holy relics. Consequently, and because of its proximity to the imperial quarters, it became one of the major ceremonial locations of the imperial palace,[8] eventually rising to be, in the words of Cyril Mango, the "palatine chapel par excellence".[9]

Already by 940, its collection of relics included the Holy Lance and a part of the True Cross, and during the next two centuries, successive emperors added more relics: the Holy Mandylion in 944, the right arm of St John the Baptist in 945, the sandals of Christ and the Holy Tile (keramion) in the 960s, the letter of Christ to King Abgar V of Edessa in 1032. By the end of the 12th century, according to accounts by Nicholas Mesarites, the church's skeuophylax, and travellers such as Anthony of Novgorod, the collection had grown to include even more relics, particularly of the Passion: the Crown of Thorns, a Holy Nail, Christ's clothes, purple mantle and reed cane, and even a piece from his tombstone.[10][11] As a result, the church was hailed by the Byzantines as "another Sinai, a Bethlehem, a Jordan, a Jerusalem, a Nazareth, a Bethany, a Galilee, a Tiberias."[4]

The French Crusader Robert of Clari, in his narrative on the sack of the city by the Crusaders in 1204, calls the church la Sainte Chapelle ("the Holy Chapel").[5] The chapel itself avoided plunder during the sack: Boniface of Montferrat moved swiftly to occupy the area of the Boukoleon Palace, and the relics passed safely on to the new Latin Emperor, Baldwin I (r. 1204–1205).[12] Over the next decades however, most of these were dispersed throughout Western Europe, given as gifts to powerful and influential rulers or sold off to procure money and supplies for the embattled and chronically cash-strapped Latin Empire.[13] Many of them, especially those pertaining to the Passion, were acquired by King Louis IX of France (r. 1226–1270). In order to house these relics, he built a dedicated palace church, characteristically named Sainte-Chapelle in direct imitation of the Virgin of the Pharos.[4][14][15] The concept was again imitated in the relic chapel of Karlstejn Castle, built by Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV (r. 1346–1378) and tied to his pretensions of being a "new Constantine".[4] The Pharos chapel itself however did not survive the Latin occupation of the city.[16]

References

- ^ Klein (2006), pp. 79–80

- ^ a b c Maguire (2004), p. 55

- ^ Lidov, Alexei (2012-10-19). "A Byzantine Jerusalem. The Imperial Pharos Chapel as the Holy Sepulchre" (PDF). In Hoffmann, Annette & Wolf, Gerhard (eds.). Jerusalem as Narrative Space / Erzählraum Jerusalem. Visualising the Middle Ages. Vol. 6. Leiden-Boston: Brill. p. 66. ISBN 978-90-04-22625-8.

- ^ a b c d Klein (2006), p. 80

- ^ a b Maguire (2004), p. 56

- ^ Mango (1986), pp. 185–186

- ^ Necipoğlu (2001), pp. 171–712

- ^ Klein (2006), p. 93

- ^ Mango (1986), p. 185

- ^ Klein (2006), pp. 91–92

- ^ Maguire (2004), pp. 56, 67–68

- ^ Angold (2003), pp. 235–236

- ^ Angold (2003), pp. 236–239

- ^ Maguire (2004), pp. 56–57

- ^ Angold (2003), p. 239

- ^ Maguire (2004), p. 57

Sources

- Angold, Michael (2003). The Fourth Crusade: Event and Context. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-582-35610-8.

- Maguire, Henry (2004). Byzantine court culture from 829 to 1204. Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-88402-308-1.

- Mango, Cyril (1986). The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312–1453: Sources and Documents. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6627-5.

- Klein, Holger A. (2006). Bauer, F.A. (ed.). "Sacred Relics and Imperial Ceremonies at the Great Palace of Constantinople" (PDF). BYZAS (5): 79–99.

- Necipoğlu, Nevra, ed. (2001). Byzantine Constantinople: Monuments, Topography and Everyday Life. Istanbul: BRILL. ISBN 90-04-11625-7.