Third party (U.S. politics)

Third party (or minor party) is a term used in the United States for political parties other than the two major parties (the Republican and Democratic parties).

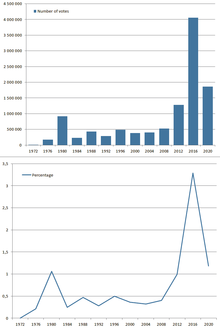

Third parties are most often encountered in presidential nominations. No third-party candidate has won the presidency since the Republican Party became a major party in the mid-19th century. Since that time, only in five elections (1892, 1912, 1924, 1948, and 1968) has a third-party candidate carried any states.[1]

Competitiveness

With few exceptions,[2] the U.S. system has two major parties which have won, on average, 98% of all state and federal seats.[3] There have only been a few rare elections where a minor party was competitive with the major parties, occasionally replacing one of the major parties in the 19th century.[4][5] The winner take all system for presidential elections and the single-seat plurality voting system for Congressional elections have over time helped establish the two-party system (see Duverger's law). Although third-party candidates rarely win elections, they can have an effect on them through vote splitting and other impacts.

Notable exceptions

Greens, Libertarians, and others have elected state legislators and local officials. The Socialist Party elected hundreds of local officials in 169 cities in 33 states by 1912, including Milwaukee, Wisconsin; New Haven, Connecticut; Reading, Pennsylvania; and Schenectady, New York.[6] There have been governors elected as independents, and from such parties as Progressive, Reform, Farmer-Labor, Populist, and Prohibition. Recent examples include Bill Walker of Alaska who was, from 2014 to 2018, the only independent governor at the time, and wrestler Jesse Ventura who was elected governor of Minnesota on the Reform Party ticket in 1998.[7]

Sometimes a national officeholder that is not a member of any party is elected. Previously, Senator Lisa Murkowski won re-election in 2010 as a write-in candidate and not as the Republican nominee, and Senator Joe Lieberman ran and won as an independent candidate in 2006 after leaving the Democratic Party.[8][9] As of 2023, there are only three U.S. senators, Angus King, Bernie Sanders and Kyrsten Sinema, who are neither Democratic nor Republican (all identify as Independent).[10]

The last time a third-party candidate carried any states in a presidential race was George Wallace in 1968, while the last third-party candidate to finish runner-up or greater was former president Teddy Roosevelt's 2nd-place finish on the Bull Moose Party ticket in 1912.[11] The only three U.S. presidents without a major party affiliation upon election were George Washington, John Tyler, and Andrew Johnson, and only Washington served his entire tenure as an independent. Neither of the other two were ever elected president in their own right, both being vice presidents who ascended to office upon the death of the president, and both became independents because they were unpopular with their parties. John Tyler was elected on the Whig ticket in 1840 with William Henry Harrison, but was expelled by his own party. Johnson was the running mate for Abraham Lincoln, who was reelected on the National Union ticket in 1864; it was a temporary name for the Republican Party.

Barriers to third party success

Winner-take-all vs. proportional representation

In winner-take-all (or plurality voting), the candidate with the largest number of votes wins, even if the margin of victory is extremely narrow or the proportion of votes received is not a majority. Unlike in proportional representation, runners-up do not gain representation in a first-past-the-post system. In the United States, systems of proportional representation are uncommon, especially above the local level and are entirely absent at the national level (even though states like Maine have introduced systems like ranked choice voting, which ensures that the voice of third party voters is heard in case none of the candidates receives a majority of preferences).[12] In Presidential elections, the majority requirement of the Electoral College, and the Constitutional provision for the House of Representatives to decide the election if no candidate receives a majority, serves as a further disincentive to third party candidacies.

In the United States, if an interest group is at odds with its traditional party, it has the option of running sympathetic candidates in primaries. Candidates failing in the primary may form or join a third party. Because of the difficulties third parties face in gaining any representation, third parties tend to exist to promote a specific issue or personality. Often, the intent is to force national public attention on such an issue. Then, one or both of the major parties may rise to commit for or against the matter at hand, or at least weigh in. H. Ross Perot eventually founded a third party, the Reform Party, to support his 1996 campaign. In 1912, Theodore Roosevelt made a spirited run for the presidency on the Progressive Party ticket, but he never made any efforts to help Progressive congressional candidates in 1914, and in the 1916 election, he supported the Republicans.

Micah Sifry argues that despite years of discontentment with the two major parties in the United States, that third parties should try to arise organically at the local level in places where ranked-choice voting and other more democratic systems makes it easier to build momentum, rather than starting with the presidency which would be incredibly unlikely to succeed.[13]

Spoiler effect

Strategic voting often leads to a third-party that underperforms its poll numbers with voters wanting to make sure their vote helps determine the winner. In response, some third-party candidates express ambivalence about which major party they prefer and their possible role as spoiler[14] or deny the possibility.[15] The two US presidential elections most consistently cited as having been spoiled by third-party candidates are 1844 and 2000.[16][17][18][19][20] This phenomenon becomes more controversial when a third-party candidate receives help from supporters of another candidate hoping they play a spoiler role.[21][22][23]

The Keys to the White House has argued that in a U.S. presidential election a significant third-party or independent campaign damages the incumbent party's candidate more, and increases the challenging party candidate's chance of winning the election[24] as it suggests public dissatisfaction with the incumbent party's candidate and policies.[citation needed]

Ballot access laws

Nationally, ballot access laws require candidates to pay registration fees and provide signatures if a party has not garnered a certain percentage of votes in previous elections.[25] In recent presidential elections, Ross Perot appeared on all 50 state ballots as an independent in 1992 and the candidate of the Reform Party in 1996. Perot, a billionaire, was able to provide significant funds for his campaigns. Patrick Buchanan appeared on all 50 state ballots in the 2000 election, largely on the basis of Perot's performance as the Reform Party's candidate four years prior. The Libertarian Party has appeared on the ballot in at least 46 states in every election since 1980, except for 1984 when David Bergland gained access in only 36 states. In 1980, 1992, 1996, 2016, and 2020 the party made the ballot in all 50 states and D.C. The Green Party gained access to 44 state ballots in 2000 but only 27 in 2004. The Constitution Party appeared on 42 state ballots in 2004. Ralph Nader, running as an independent in 2004, appeared on 34 state ballots. In 2008, Nader appeared on 45 state ballots and the D.C. ballot.

Debate rules

Presidential debates between the nominees of the two major parties first occurred in 1960, then after three cycles without debates, resumed in 1976. Third party or independent candidates have been in debates in only two cycles. Ronald Reagan and John Anderson debated in 1980, but incumbent President Carter refused to appear with Anderson, and Anderson was excluded from the subsequent debate between Reagan and Carter. Independent Ross Perot was included in all three of the debates with Republican George H. W. Bush and Democrat Bill Clinton in 1992, largely at the behest of the Bush campaign.[citation needed] His participation helped Perot climb from 7% before the debates to 19% on Election Day.[26]

Perot did not make the 1996 debates.[27] In 2000, revised debate access rules made it even harder for third-party candidates to gain access by stipulating that, besides being on enough state ballots to win an Electoral College majority, debate participants must clear 15% in pre-debate opinion polls. This rule has continued being in effect as of 2008.[28][29] The 15% criterion, had it been in place, would have prevented Anderson and Perot from participating in the debates in which they appeared. Debates in other state and federal elections often exclude independent and third-party candidates, and the Supreme Court has upheld this practice in several cases. The Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD) is a private company.[30]

Major parties adopt third-party platforms

They can draw attention to issues that may be ignored by the majority parties. If such an issue finds acceptance with the voters, one or more of the major parties may adopt the issue into its own party platform. A third-party candidate will sometimes strike a chord with a section of voters in a particular election, bringing an issue to national prominence and amount a significant proportion of the popular vote. Major parties often respond to this by adopting this issue in a subsequent election. After 1968, under President Nixon the Republican Party adopted a "Southern Strategy" to win the support of conservative Democrats opposed to the Civil Rights Movement and resulting legislation and to combat local third parties. This can be seen as a response to the popularity of segregationist candidate George Wallace who gained 13.5% of the popular vote in the 1968 election for the American Independent Party. In 1996, both the Democrats and the Republicans agreed to deficit reduction on the back of Ross Perot's popularity in the 1992 election. This severely undermined Perot's campaign in the 1996 election.

However, changing positions can be costly for a major party. For example, in the US 2000 Presidential election Magee predicts that Gore shifted his positions to the left to account for Nader, which lost him some valuable centrist voters to Bush.[31] In cases with an extreme minor candidate, not changing positions can help to reframe the more competitive candidate as moderate, helping to attract the most valuable swing voters from their top competitor while losing some voters on the extreme to the less competitive minor candidate.[32]

Current U.S. third parties

Largest

| Party | No. registrations[33] | % registered voters[33] |

|---|---|---|

| Democratic Party | 47,130,651 | 38.73% |

| Republican Party | 36,019,694 | 29.60% |

| Libertarian Party | 732,865 | 0.6% |

| Green Party | 234,120 | 0.19% |

| Constitution Party | 128,914 | 0.11% |

Smallest parties (listed by ideology)

This section includes only parties that have actually run candidates under their name in recent years.

Right-wing

This section includes any party that advocates positions associated with American conservatism, including both Old Right and New Right ideologies.

State-only right-wing parties

- American Independent Party (California)

- Conservative Party of New York State

- Constitution Party of Oregon

Centrist

This section includes any party that is independent, populist, or any other that either rejects left–right politics or does not have a party platform.

- Alliance Party

- American Solidarity Party

- Citizens Party

- Forward Party/Forward

- No Labels

- Reform Party of the United States of America

- Serve America Movement

- United States Pirate Party

- Unity Party of America

State-only centrist parties

- Moderate Party of Rhode Island

- Independent Party of Delaware

- Independent Party of Oregon

- Keystone Party of Pennsylvania

- United Utah Party

Left-wing

This section includes any party that has a left-liberal, progressive, social democratic, democratic socialist, or Marxist platform.

- Communist Party USA

- Freedom Socialist Party

- Justice Party USA

- People's Party

- Party for Socialism and Liberation

- Peace and Freedom Party

- Socialist Action

- Socialist Equality Party

- Socialist Alternative

- Socialist Party USA

- Socialist Workers Party

- Working Class Party

- Workers World Party

- Working Families Party

State-only left-wing parties

- Charter Party (Cincinnati, Ohio, only)

- Green Mountain Peace and Justice Party (Vermont)

- Green Party of Alaska

- Green Party of Rhode Island

- Labor Party (South Carolina)

- Liberal Party of New York

- Oregon Progressive Party

- Progressive Dane (Dane county, Wisconsin)

- United Independent Party (Massachusetts)

- Vermont Progressive Party

- Washington Progressive Party

Ethnic nationalism

This section includes parties that primarily advocate for granting special privileges or consideration to members of a certain race, ethnic group, religion etc.

- American Freedom Party

- Black Riders Liberation Party

- National Socialist Movement

- New Afrikan Black Panther Party

Also included in this category are various parties found in and confined to Native American reservations, almost all of which are solely devoted to the furthering of the tribes to which the reservations were assigned. An example of a particularly powerful tribal nationalist party is the Seneca Party that operates on the Seneca Nation of New York's reservations.[34]

Secessionist parties

This section includes parties that primarily advocate for Independence from the United States. (Specific party platforms may range from left wing to right wing).

Single-issue/protest-oriented

This section includes parties that primarily advocate single-issue politics (though they may have a more detailed platform) or may seek to attract protest votes rather than to mount serious political campaigns or advocacy.

- Grassroots—Legalize Cannabis Party

- Legal Marijuana Now Party

- Prohibition Party

- United States Marijuana Party[citation needed]

State-only parties

- Approval Voting Party (Colorado)

- Natural Law Party (Michigan)

- New York State Right to Life Party

- Rent Is Too Damn High Party (New York)

See also

- Equal-time rule

- Third-party and independent members of the United States House of Representatives

- United States Electoral College

- Independent politician

- Political party

- Political parties in the United States

- Proportional representation

- Third party (politics)

- Suffrage

References

- ^ "U.S. presidential elections: third-party performance 1892-2020". Statista. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ Arthur Meier Schlesinger, ed. History of US political parties (5 vol. Chelsea House Pub, 2002).

- ^ Masket, Seth (Fall 2023). "Giving Minor Parties a Chance". Democracy (journal). 70.

- ^ Blake, Aaron (November 25, 2021). "Why are there only two parties in American politics?". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ Riker, William H. (December 1982). "The Two-party System and Duverger's Law: An Essay on the History of Political Science". American Political Science Review. 76 (4): 753–766. doi:10.1017/s0003055400189580. JSTOR 1962968. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ Nichols, John (2011). The "S" Word: A Short History of an American Tradition. Verso. p. 104. ISBN 9781844676798.

- ^ Kettle, Martin (February 12, 2000). "Ventura quits Perot's Reform party". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ "Senator Lisa Murkowski wins Alaska write-in campaign". Reuters. November 18, 2010. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ Zeller, Shawn. "Crashing the Lieberman Party - New York Times". archive.nytimes.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2018. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ "Justin Amash Becomes the First Libertarian Member of Congress". Reason.com. April 29, 2020. Archived from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- ^ "U.S. presidential elections: third-party performance 1892-2020". Statista. Retrieved May 25, 2023.

- ^ Naylor, Brian (October 7, 2020). "How Maine's Ranked-Choice Voting System Works". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Sifry, Micah L. (February 2, 2018). "Why America Is Stuck With Only Two Parties". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Selk, Avi (November 25, 2021). "Analysis | Green Party candidate says he might be part alien, doesn't care if he's a spoiler in Ohio election". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Means, Marianne (February 4, 2001). "Opinion: Goodbye, Ralph". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on May 26, 2002.

{cite web}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Green, Donald J. (2010). Third-party matters: politics, presidents, and third parties in American history. Santa Barbara, Calif: Praeger. pp. 153–154. ISBN 978-0-313-36591-1.

- ^ Devine, Christopher J.; Kopko, Kyle C. (September 1, 2021). "Did Gary Johnson and Jill Stein Cost Hillary Clinton the Presidency? A Counterfactual Analysis of Minor Party Voting in the 2016 US Presidential Election". The Forum. 19 (2): 173–201. doi:10.1515/for-2021-0011. ISSN 1540-8884.

- ^ Herron, Michael C.; Lewis, Jeffrey B. (April 24, 2006). "Did Ralph Nader spoil Al Gore's Presidential bid? A ballot-level study of Green and Reform Party voters in the 2000 Presidential election". Quarterly Journal of Political Science. Now Publishing Inc. 2 (3): 205–226. doi:10.1561/100.00005039. Pdf.

- ^ Burden, Barry C. (September 2005). "Ralph Nader's Campaign Strategy in the 2000 U.S. Presidential Election". American Politics Research. 33 (5): 672–699. doi:10.1177/1532673x04272431. ISSN 1532-673X.

- ^ Roberts, Joel (July 27, 2004). "Nader to crash Dems' party?". CBS News.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie; Hakim, Danny; Corasaniti, Nick (September 22, 2020). "How Republicans Are Trying to Use the Green Party to Their Advantage". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ Schreckinger, Ben (June 20, 2017). "Jill Stein Isn't Sorry". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ "Russians launched pro-Jill Stein social media blitz to help Trump, reports say". NBC News. Retrieved May 11, 2023.

- ^ "The 13 Keys to the White House". American University. May 4, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2023.

- ^ Amato, Theresa (December 4, 2009). "The two party ballot suppresses third party change". The Record. Harvard Law. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

Today, as in 1958, ballot access for minor parties and Independents remains convoluted and discriminatory. Though certain state ballot access statutes are better, and a few Supreme Court decisions (Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1968), Anderson v. Celebrezze, 460 U.S. 780 (1983)) have been generally favorable, on the whole, the process—and the cumulative burden it places on these federal candidates—may be best described as antagonistic. The jurisprudence of the Court remains hostile to minor party and Independent candidates, and this antipathy can be seen in at least a half dozen cases decided since Nader's article, including Jenness v. Fortson, 403 U.S. 431 (1971), American Party of Tex. v. White, 415 U.S. 767 (1974), Munro v. Socialist Workers Party, 479 U.S. 189 (1986), Burdick v. Takushi, 504 U.S. 428 (1992), and Arkansas Ed. Television Comm'n v. Forbes, 523 U.S. 666 (1998). Justice Rehnquist, for example, writing for a 6–3 divided Court in Timmons v. Twin Cities Area New Party, 520 U.S. 351 (1997), spells out the Court's bias for the "two-party system," even though the word "party" is nowhere to be found in the Constitution. He wrote that "The Constitution permits the Minnesota Legislature to decide that political stability is best served through a healthy two-party system. And while an interest in securing the perceived benefits of a stable two-party system will not justify unreasonably exclusionary restrictions, States need not remove all the many hurdles third parties face in the American political arena today." 520 U.S. 351, 366–67.

- ^ "What Happened in 1992?", Open Debates, archived from the original on April 15, 2013, retrieved December 20, 2007

- ^ "What Happened in 1996?", Open Debates, archived from the original on April 15, 2013, retrieved December 20, 2007

- ^ "The 15 Percent Barrier", Open Debates, archived from the original on April 15, 2013, retrieved December 20, 2007

- ^ Commission on Presidential Debates Announces Sites, Dates, Formats and Candidate Selection Criteria for 2008 General Election, Commission on Presidential Debates, November 19, 2007, archived from the original on November 19, 2008, retrieved December 20, 2007

- ^ Lister, J (September 1980), "1980 Debates", The New England Journal of Medicine, Commission on Presidential Debates, 303 (13): 741–44, doi:10.1056/NEJM198009253031307, PMID 6157090, archived from the original on January 1, 2008, retrieved December 20, 2007

- ^ Magee, Christopher S. P. (2003). "Third-Party Candidates and the 2000 Presidential Election". Social Science Quarterly. 84 (3): 574–595. ISSN 0038-4941.

- ^ Wang, Austin Horng-En; Chen, Fang-Yu (2019). "Extreme Candidates as the Beneficent Spoiler? Range Effect in the Plurality Voting System". Political Research Quarterly. 72 (2): 278–292. ISSN 1065-9129.

- ^ a b Winger, Richard (December 27, 2022). "December 2022 Ballot Access News Print Edition". Ballot Access News. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Herbeck, Dan (November 15, 2011). Resentments abound in Seneca power struggle Archived November 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. The Buffalo News. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

Further reading

Surveys

- Epstein, David A. (2012). Left, Right, Out: The History of Third Parties in America. Arts and Letters Imperium Publications. ISBN 978-0-578-10654-0

- Gillespie, J. David. Challengers to Duopoly: Why Third Parties Matter in American Two-Party Politics (University of South Carolina Press, 2012)

- Green, Donald J. Third-Party Matters: Politics, Presidents, and Third Parties in American History (Praeger, 2010)

- Herrnson, Paul S. and John C. Green, eds. Multiparty Politics in America (Rowman & Littlefield, 1997)

- Hesseltine, William B. Third-Party Movements in the United States (1962), Brief survey

- Hicks, John D. "The Third Party Tradition in American Politics." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 20 (1933): 3–28. in JSTOR

- Kruschke, Earl R. Encyclopedia of Third Parties in the United States (ABC-CLIO, 1991)

- Ness, Immanuel and James Ciment, eds. Encyclopedia of Third Parties in America (4 vol. 2006)

- Richardson, Darcy G. Others: Third Party Politics from the Nation's Founding to the Rise and Fall of the Greenback-Labor Party. Vol. 1. iUniverse, 2004.

- Rosenstone, Steven J., Roy L. Behr, and Edward H. Lazarus. Third Parties in America: Citizen Response to Major Party Failure (2nd ed. Princeton University Press, 1996)

- Schlesinger, Arthur Meier Jr. ed. History of U.S. Political Parties (1973) multivolume compilation includes essays by experts on the more important third parties, plus some primary sources

- Sifry, Micah L. Spoiling for a Fight: Third Party Politics in America (Routledge, 2002)

Scholarly studies

- Abramson Paul R., John H. Aldrich, Phil Paolino, and David W. Rohde. "Third-Party and Independent Candidates in American Politics: Wallace, Anderson, and Perot." Political Science Quarterly 110 (1995): 349–67

- Argersinger, Peter H. The Limits of Agrarian Radicalism: Western Populism and American Politics (University Press of Kansas, 1995)

- Berg, John C. "Beyond a Third Party: The Other Minor Parties in the 1996 Elections", in The State of the Parties: The Changing Role of Contemporary American Parties ed by Daniel M. Shea and John C. Green (3rd ed. Rowman & Littlefield, 1998), pp. 212–28

- Berg, John C. "Spoiler or Builder? The Effect of Ralph Nader's 2000 Campaign on the U.S. Greens." in The State of the Parties: The Changing Role of Contemporary American Parties, (4th ed. 2003) edited by John C. Green and Rick Farmer, pp. 323–36.

- Brooks, Corey M. Liberty Power: Antislavery Third Parties and the Transformation of American Politics (University of Chicago Press, 2016). 302 pp.

- Burden, Barry C. "Ralph Nader's Campaign Strategy in the 2000 U.S. Presidential Election." American Politics Research 33 (2005): 672–99.

- Carlin, Diana B., and Mitchell S. McKinney, eds. The 1992 Presidential Debates in Focus (1994), includes Ross Parot

- Chace, James. 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft and Debs – The Election that Changed the Country (2009)

- Darsey, James. "The Legend of Eugene Debs: Prophetic Ethos as Radical Argument." Quarterly Journal of Speech 74 (1988): 434–52.

- Gould, Lewis L. Four Hats in the Ring: The 1912 Election and the Birth of Modern American Politics (2008)

- Hazlett, Joseph. The Libertarian Party and Other Minor Political Parties in the United States (McFarland & Company, 1992)

- Hogan, J. Michael. "Wallace and the Wallacites: A Reexamination." Southern Speech Communication Journal 50 (1984): 24–48. On George Wallace in 1968

- Jelen, Ted G. ed. Ross for Boss: The Perot Phenomenon and Beyond (State University of New York Press, 2001)

- Koch, Jeffrey. "The Perot Candidacy and Attitudes Toward Government and Politics." Political Research Quarterly 51 (1998): 141–53.

- Koch, Jeffrey. "Political Cynicism and Third Party Support in American Presidential Elections", American Politics Research 31 (2003): 48–65.

- Lee, Michael J. "The Populist Chameleon: The People's Party, Huey Long, George Wallace, and the Populist Argumentative Frame." Quarterly Journal of Speech (2006): 355–78.

- Mowry, George E. Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement (1946), on 1912

- Rapoport, Ronald B., and Walter J. Stone. Three's a Crowd: The Dynamic of Third Parties, Ross Perot, and Republican Resurgence (University of Michigan Press, 2005)

- Richardson, Darcy G. Others: Third Parties During the Populist Period (2007) 506 pp

- Richardson, Darcy G. A Toast to Glory: The Prohibition Party Flirts With Greatness 59 pp

- Rohler, Lloyd. "Conservative Appeals to the People: George Wallace's Populist Rhetoric." Southern Communication Journal 64 (1999): 316–22.

- Rohler, Lloyd. George Wallace: Conservative Populist (Praeger, 2004)

- Rosenfeld, Lawrence W. "George Wallace Plays Rosemary's Baby." Quarterly Journal of Speech 55 (1969): 36–44.

- Ross, Jack. The Socialist Party of America: A Complete History (2015) 824 pp

- Shepard, Ryan Michael. "Deeds done in different words: a genre-based approach to third party presidential campaign discourse." (PhD Ddissertation, University of Kansas 2011) online

- Tamas, Bernard. 2018. The Demise and Rebirth of American Third Parties: Poised for Political Revival? Routledge.

External links

- The Importance of Ballot Access, essay by Richard Winger

- Ballot Access News – Ballot Access news on all parties

- Free and Equal – Election Reform to end partisan duopoly

- Independent Political Report – Frequently updated source for third party news