Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 26, 1840 |

| Died | December 7, 1902 (aged 62) |

| Political party | Republican |

| Signature | |

| |

Thomas Nast (/næst/; German: [nast]; September 26, 1840[1] – December 7, 1902) was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist often considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon".[2]

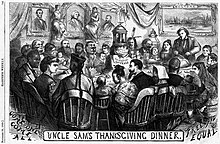

He was a critic of Democratic Representative "Boss" Tweed and the Tammany Hall Democratic party political machine. He created a modern version of Santa Claus (based on the traditional German figures of Sankt Nikolaus and Weihnachtsmann) and the political symbol of the elephant for the Republican Party (GOP). Contrary to popular belief, Nast did not create Uncle Sam (the male personification of the United States Federal Government), Columbia (the female personification of American values), or the Democratic donkey,[3] although he did popularize those symbols through his artwork. Nast was associated with the magazine Harper's Weekly from 1859 to 1860 and from 1862 until 1886. Nast's influence was so widespread that Theodore Roosevelt once said, "Thomas Nast was our best teacher."

Early life and education

Nast was born in military barracks in Landau, Bavaria, Germany (now in Rhineland-Palatinate), as his father was a trombonist in the Bavarian 9th regiment band.[4] Nast was the last child of Appolonia (née Abriss) and Joseph Thomas Nast. He had an older sister Andie; two other siblings had died before he was born. His father held political convictions that put him at odds with the Bavarian government, so in 1846, Joseph Nast left Landau, enlisting first on a French man-of-war and subsequently on an American ship.[5] He sent his wife and children to New York City, where they arrived in June 1846,[6] and at the end of his enlistment in 1850, he joined them there.[7]

Nast attended school in New York City from the age of six to 14. He did poorly at his lessons, but his passion for drawing was apparent from an early age. In 1854, at the age of 14, he was enrolled for about a year of study with Alfred Fredericks and Theodore Kaufmann, and then at the school of the National Academy of Design.[8][9] In 1856, he started working as a draftsman for Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper.[10] His drawings appeared for the first time in Harper's Weekly on March 19, 1859,[11] when he illustrated a report exposing police corruption; Nast was 18 years old at that point.[12]

Career

In February 1860, he went to England for the New York Illustrated News to depict one of the major sporting events of the era, the prize fight between the American John C. Heenan and the English Thomas Sayers[13] sponsored by George Wilkes, publisher of Wilkes' Spirit of the Times. A few months later, as artist for The Illustrated London News, he joined Garibaldi in Italy. Nast's cartoons and articles about the Garibaldi military campaign to unify Italy captured the popular imagination in the U.S. In February 1861, he arrived back in New York. In September of that year, he married Sarah Edwards, whom he had met two years earlier.

He left the New York Illustrated News to work again, briefly, for Frank Leslie's Illustrated News.[14] In 1862, he became a staff illustrator for Harper's Weekly. In his first years with Harper's, Nast became known especially for compositions that appealed to the sentiment of the viewer. An example is "Christmas Eve" (1862), in which a wreath frames a scene of a soldier's praying wife and sleeping children at home; a second wreath frames the soldier seated by a campfire, gazing longingly at small pictures of his loved ones.[15] One of his most celebrated cartoons was "Compromise with the South" (1864), directed against those in the North who opposed the prosecution of the American Civil War.[16] He was known for drawing battlefields in border and southern states. These attracted great attention, and Nast was referred to by President Abraham Lincoln as "our best recruiting sergeant".[17]

After the war, Nast strongly opposed the anti-Reconstruction policy of President Andrew Johnson, whom he depicted in a series of trenchant cartoons that marked "Nast's great beginning in the field of caricature".[18]

Style and themes

Nast's cartoons frequently had numerous sidebars and panels with intricate subplots to the main cartoon. A Sunday feature could provide hours of entertainment and highlight social causes. After 1870, Nast favored simpler compositions featuring a strong central image.[8] He based his likenesses on photographs.[8]

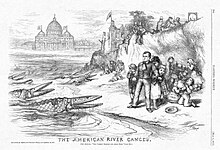

In the early part of his career, Nast used a brush and ink wash technique to draw tonal renderings onto the wood blocks that would be carved into printing blocks by staff engravers.[19] The bold cross-hatching that characterized Nast's mature style resulted from a change in his method that began with a cartoon of June 26, 1869, which Nast drew onto the wood block using a pencil, so that the engraver was guided by Nast's linework. This change of style was influenced by the work of the English illustrator John Tenniel.[20] A recurring theme in Nast's cartoons is anti-Catholicism.[21][22] Nast was baptized a Catholic at the Saint Maria Catholic Church in Landau,[23] and for a time received Catholic education in New York City.[24] When Nast converted to Protestantism remains unclear, but his conversion was likely formalized upon his marriage in 1861. (The family were practicing Episcopalians at St. Peter's in Morristown.) Nast considered the Catholic Church to be a threat to American values. According to his biographer, Fiona Deans Halloran, Nast was "intensely opposed to the encroachment of Catholic ideas into public education".[25] When Tammany Hall proposed a new tax to support parochial Catholic schools, he was outraged. His savage 1871 cartoon "The American River Ganges", depicts Catholic bishops, guided by Rome, as crocodiles moving in to attack American school children as Irish politicians prevent their escape. He portrayed public support for religious education as a threat to democratic government. The authoritarian papacy in Rome, ignorant Irish Americans, and corrupt politicians at Tammany Hall figured prominently in his work. Nast favored nonsectarian public education that mitigated differences of religion and ethnicity. However, in 1871 Nast and Harper's Weekly supported the Republican-dominated board of education in Long Island in requiring students to hear passages from the King James Bible, and his educational cartoons sought to raise anti-Catholic and anti-Irish fervor among Republicans and independents.[26]

Nast expressed anti-Irish sentiment by depicting them as violent drunks. He used Irish people as a symbol of mob violence, machine politics, and the exploitation of immigrants by political bosses.[27] Nast's emphasis on Irish violence may have originated in scenes he witnessed in his youth. Nast was physically small and had experienced bullying as a child.[28] In the neighborhood in which he grew up, acts of violence by the Irish against black Americans were commonplace.[29]

In 1863, he witnessed the New York City draft riots in which a mob composed mainly of Irish immigrants burned the Colored Orphan Asylum to the ground. His experiences may explain his sympathy for black Americans and his "antipathy to what he perceived as the brutish, uncontrollable Irish thug".[28] An 1876 Nast cartoon combined a caricature of Charles Francis Adams Sr with anti-Irish sentiment and anti-Fenianship.[30]

In general, his political cartoons supported American Indians and Chinese Americans.[31] He advocated the abolition of slavery, opposed racial segregation, and deplored the violence of the Ku Klux Klan. In one of his more famous cartoons, the phrase "Worse than Slavery" is printed on a coat of arms depicting a despondent black family holding their dead child; in the background is a lynching and a schoolhouse destroyed by arson. Two members of the Ku Klux Klan and White League, paramilitary insurgent groups in the Reconstruction-era South, shake hands in their mutually destructive work against black Americans.[32]

-

September 1868 Nast cartoon "This is a White Man's Government!" depicting left to right a stereotyped Irishman (representing a Northern Democratic party member), an ex-Confederate soldier (Nathan B. Forrest, representing a Southern Democratic party member), and Democratic party chairman August Belmont "triumphing" over a prostrate USCT soldier

-

The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things, a Nast cartoon depicting a drunken Irishman lighting a powder keg. Published in Harper's Weekly, September 2, 1871

-

1871 Nast cartoon: "Move on! Has the Native American no rights that the naturalized American is bound to respect?" (while naturalized foreigners had the vote, Native Americans had no vote, as they were not considered United States citizens, which was not remedied until 1924.)

-

1879 Nast cartoon: "Red gentleman (Indian) to yellow gentleman (Chinese) "Pale face 'fraid you crowd him out, as he did me." In the left background an African American remarks "My day is coming".

-

Nast's cartoon "Third Term Panic". Inspired by the tale of The Ass in the Lion's Skin and a rumor of President Grant seeking a third term, the Democratic donkey (labeled "Caesarism") panics the other political animals, including a Republican Party elephant.

-

October 24, 1874, Nast cartoon "The Union as it was...This is a White Mans Government....the Lost cause...Worse than Slavery"

-

"Colored Rule in a Reconstructed(?) State", Harper's Weekly, March 14, 1874. By this point, Nast had given up on racial idealism and caricatured black legislators as incompetent buffoons.

Despite Nast's championing of minorities, Morton Keller writes that later in his career "racist stereotypy of blacks began to appear: comparable to those of the Irish—though in contrast with the presumably more highly civilized Chinese."[33]

Nast introduced into American cartoons the practice of modernizing scenes from Shakespeare for a political purpose.[citation needed]

Nast also brought his approach to bear on the usually prosaic almanac business, publishing an annual Nast's Illustrated Almanac from 1871 to 1875. [34] The Green Bag republished all five of Nast's almanacs in the 2011 edition of its Almanac & Reader.[35]

Campaign against the Tweed Ring

Boss Tweed depicted by Thomas Nast in a wood engraving published in Harper's Weekly, October 21, 1871

Nast's drawings were instrumental in the downfall of Boss Tweed, the powerful Tammany Hall leader.[36] As commissioner of public works for New York City, Tweed led a ring that by 1870 had gained total control of the city's government, and controlled "a working majority in the State Legislature".[37] Tweed and his associates—Peter Barr Sweeny (park commissioner), Richard B. Connolly (controller of public expenditures), and Mayor A. Oakey Hall—defrauded the city of many millions of dollars by grossly inflating expenses paid to contractors connected to the Ring.[38] Nast, whose cartoons attacking Tammany corruption had appeared occasionally since 1867, intensified his focus on the four principal players in 1870 and especially in 1871.[39]

Tweed so feared Nast's campaign that he sent an emissary to offer the artist a bribe of $100,000, which was represented as a gift from a group of wealthy benefactors to enable Nast to study art in Europe.[40] Feigning interest, Nast negotiated for more before finally refusing an offer of $500,000 with the words, "Well, I don't think I'll do it. I made up my mind not long ago to put some of those fellows behind the bars".[41] Nast pressed his attack in the pages of Harper's, and the Ring was removed from power in the election of November 7, 1871.[42] Tweed was arrested in 1873 and convicted of fraud. When Tweed attempted to escape justice in December 1875 by fleeing to Cuba and from there to Spain, officials in Vigo were able to identify the fugitive by using one of Nast's cartoons.[43]

Party politics

Nast was the first journalist who did not own his newspaper to play a major role in shaping public opinion. His cartoons were influential in deciding five Presidential elections: Abraham Lincoln (1864); Ulysses S. Grant (1868 and 1872); Rutherford B. Hayes (1876); — all Republicans — and Democrat Grover Cleveland (1884). His biting cartoons ridiculed the losers: George B. McClellan (1864); Horatio Seymour (1868); Horace Greeley (1872); Samuel J. Tilden (1876); and James G. Blaine (1884). Nast effectively sat out the 1880 election because he distrusted Republican James A. Garfield (who won) and admired Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock, a Civil War hero and Nast’s personal friend.

In addition to his talent, creativity and the repetitive impact of his cartoons, Nast benefited from his lack of meaningful competition before Puck arrived in 1877, and from the financial strength, editorial consistency and reach of Harper’s Weekly. America’s leading illustrated newspaper’s circulation was about 120,000 during the Civil War, 200,000 during subsequent Presidential elections, and almost 300,000 during the height of the Tweed campaign. With passalong readership, Nast’s audience reached 500,000 to more than a million viewers.[46]

The single most important and influential cartoon that Nast ever drew appeared in Harper’s Weekly on August 24, 1864 (post-dated September 3) as the Democratic National Committee was assembling in Chicago to nominate McClellan (whom Lincoln had fired as his top Union general two years earlier) for President. “Compromise with the South — Dedicated to the Chicago Convention” captured the very crux of the existential emotional and political stake at issue in the forthcoming election.

Nast’s scathing caricature featured an arrogant, exultant Jefferson Davis shaking hands with a crippled Union soldier who — with his head bowed and his only leg shackled to a ball and chain — humbly accepted it. Columbia, representing the Union and modeled by Nast’s wife Sallie, wept at the gravestone marked “In Memory of Our Union Heroes Who Fell in a Useless War.” As Davis’s boot stomped on a Union grave and broke the sword of Northern Power, the cat-o’-nine-tails in his left hand was ready to flog his vanquished enemies. A Black family in chains despaired behind Davis. The Union flag, upside down in distress, recited it successes, including emancipation, on its stripes; the Confederate flag detailed a list of atrocities.

On October 16 — almost eight weeks after Nast’s cartoon appeared — the Richmond Enquirer published some more extreme demands which were not in the Democratic platform. Lincoln’s reelection managers took Nast’s cartoon, added “The Rebel Terms of Peace,” and made more than a million copies as campaign posters. In combination with General William T. Sherman’s capture of Atlanta on September 1 and General Phil Sheridan’s victory in the Shenandoah Valley on October 19, “A Traitor’s Peace” probably was the single most effective visual campaign advertisement in any American Presidential election before or since.[47]

Nast played an important role during the presidential election in 1868, and Ulysses S. Grant attributed his victory to "the sword of Sheridan and the pencil of Thomas Nast."[48] In the 1872 presidential campaign, Nast's ridicule of Horace Greeley's candidacy was especially merciless.[49] After Grant's victory in 1872, Mark Twain wrote the artist a letter saying: "Nast, you more than any other man have won a prodigious victory for Grant—I mean, rather, for Civilization and Progress."[50] Nast became a close friend of President Grant and the two families shared regular dinners until Grant's death in 1885.

Nast and his wife moved to Morristown, New Jersey in 1872[51] and there they raised a family that eventually numbered five children.[citation needed] In 1873, Nast toured the United States as a lecturer and a sketch-artist.[52] His activity on the lecture circuit made him wealthy.[53] Nast was for many years a staunch Republican.[54] Nast opposed inflation of the currency, notably with his famous rag-baby cartoons, and he played an important part in securing Rutherford B. Hayes' ultimate victory in the presidential election in 1876.[55] Hayes later remarked that Nast was "the most powerful, single-handed aid [he] had",[56] but Nast quickly became disillusioned with President Hayes, whose lenient policy towards the South in removing federal troops he opposed.[57]

The death of the Weekly's publisher, Fletcher Harper, in 1877 resulted in a changed relationship between Nast and his editor George William Curtis. His cartoons appeared less frequently, and he was not given free rein to criticize Hayes or his policies.[58] Beginning in the late 1860s, Nast and Curtis had frequently differed on political matters and particularly on the role of cartoons in political discourse.[59] Curtis believed that the powerful weapon of caricature should be reserved for "the Ku-Klux Democracy" of the opposition party, and did not approve of Nast's cartoons assailing Republicans such as Carl Schurz and Charles Sumner who opposed policies of the Grant administration.[60] Nast said of Curtis: "When he attacks a man with his pen it seems as if he were apologizing for the act. I try to hit the enemy between the eyes and knock him down."[33] Fletcher Harper consistently supported Nast in his disputes with Curtis.[59] After his death, his nephews, Joseph W. Harper Jr. and John Henry Harper, assumed control of the magazine and were more sympathetic to Curtis's arguments for rejecting cartoons that contradicted his editorial positions.[61]

Between 1877 and 1884, Nast's work appeared only sporadically in Harper's, which began publishing the milder political cartoons of William Allen Rogers. Although his sphere of influence was diminishing, from this period date dozens of his pro-Chinese immigration drawings, often implicating the Irish as instigators. Nast blamed U.S. Senator James G. Blaine (R-Maine) for his support of the Chinese Exclusion Act and depicted Blaine with the same zeal used against Tweed. Nast was one of the few editorial artists who took up for the cause of the Chinese in America.[62]

During the presidential election of 1880, Nast felt that he could not support the Republican candidate, James A. Garfield, because of Garfield's involvement in the Crédit Mobilier scandal; and did not wish to attack the Democratic candidate, Winfield Scott Hancock, his personal friend and a Union general whose integrity commanded respect. As a result, "Nast's commentary on the 1880 campaign lacked passion", according to Halloran.[63] He submitted no cartoons to Harper's between the end of March 1883 and March 1, 1884, partly because of illness.[64]

In 1884, Curtis and Nast agreed that they could not support the Republican candidate James G. Blaine, a proponent of high tariffs and the spoils system whom they perceived as personally corrupt.[65] Instead, they became Mugwumps by supporting the Democratic candidate, Grover Cleveland, whose platform of civil service reform appealed to them. Nast's cartoons helped Cleveland become the first Democrat to be elected President since 1856. In the words of the artist's grandson, Thomas Nast St Hill, "it was generally conceded that Nast's support won Cleveland the small margin by which he was elected. In this his last national political campaign, Nast had, in fact, 'made a president'."[66]

Nast's tenure at Harper's Weekly ended with his Christmas illustration of December 1886. It was said by the journalist Henry Watterson that "in quitting Harper's Weekly, Nast lost his forum: in losing him, Harper's Weekly lost its political importance."[67] Fiona Deans Halloran says "the former is true to a certain extent, the latter unlikely."[68]

Nast lost most of his fortune in 1884 after investing in a banking and brokerage firm operated by the swindler Ferdinand Ward. In need of income, Nast returned to the lecture circuit in 1884 and 1887.[69] Although these tours were successful, they were less remunerative than the lecture series of 1873.[70]

After Harper's Weekly

In 1890, Nast published Thomas Nast's Christmas Drawings for the Human Race.[8] He contributed cartoons in various publications, notably the Illustrated American, but was unable to regain his earlier popularity. His mode of cartooning had come to be seen as outdated, and a more relaxed style exemplified by the work of Joseph Keppler was in vogue.[71] Health problems, which included pain in his hands which had troubled him since the 1870s, affected his ability to work.

In 1892, he took control of a failing magazine, the New York Gazette, and renamed it Nast's Weekly. Now returned to the Republican fold, Nast used the Weekly as a vehicle for his cartoons supporting Benjamin Harrison for president. The magazine had little impact and ceased publication seven months after it began, shortly after Harrison's defeat.[72]

The failure of Nast's Weekly left Nast with few financial resources. He received a few commissions for oil paintings and drew book illustrations. In 1902, he applied for a job in the State Department, hoping to secure a consular position in western Europe.[73] Although no such position was available, President Theodore Roosevelt was an admirer of the artist and offered him an appointment as the United States' Consul General to Guayaquil, Ecuador in South America.[73] Nast accepted the position and traveled to Ecuador on July 1, 1902.[73] During a subsequent yellow fever outbreak, Nast remained on the job, helping numerous diplomatic missions and businesses escape the contagion. He contracted the disease and died on December 7 of that year.[8] His body was returned to the United States, where he was interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.

Legacy

Nast's depictions of iconic characters, such as Santa Claus[74] and Uncle Sam, are widely credited as forming the basis of popular depictions used today. Additional contributions by Nast include:

- Republican Party elephant[75]

- Democratic Party donkey (although the donkey was associated with the Democrats as early as 1837, Nast popularized the representation[76])

- Tammany Hall tiger, a symbol of Boss Tweed's political machine

- Uncle Sam, a lanky avuncular personification of the United States (first drawn in the 1830s; Nast and John Tenniel added the goatee)

- John Confucius, a variation of John Chinaman, a traditional caricature of a Chinese immigrant

- The Fight at Dame Europa's School, 1871

- Peace In Union, a 9 ft (2.7 m) by 12 ft (3.7 m) oil painting which depicts the surrender of General Robert E. Lee to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse in April 1865. The painting was a commission from Herman Kohlsaat in 1894. Upon its completion in 1895 it was presented as a gift to the citizens of Galena, Illinois.

In December 2011, a proposal to include Nast in the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2012 caused controversy. The Wall Street Journal reported that because of his stereotypical cartoons of the Irish, a number of objections were raised about Nast's work. For example, "The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things" portrays an Irishman as being sub-human, drunk, and violent.[77]

Thomas Nast Award

The Thomas Nast Award[78] has been presented each year since 1968 by the Overseas Press Club[79] to an editorial cartoonist for the "best cartoons on international affairs." Past winners include Signe Wilkinson, Kevin (KAL) Kallaugher, Mike Peters, Clay Bennett, Mike Luckovich, Tom Toles, Herbert Block, Tony Auth, Jeff MacNelly, Dick Locher, Jim Morin, Warren King, Tom Darcy, Don Wright and Patrick Chappatte.[78][79]

In December 2018, The OPC Board of Governors decided to remove Nast's name from the award noting that Nast "exhibited an ugly bias against immigrants, the Irish and Catholics". OPC President Pancho Bernasconi stated "Once we became aware of how some groups and ethnicities were portrayed in a manner that is not consistent with how journalists work and view their role today, we voted to remove his name from the award."[80]

Thomas Nast Prize

The Thomas Nast Prize for editorial cartooning has been awarded by the Thomas Nast Foundation (located in Nast's birthplace of Landau, Germany) since 1978 when it was first given to Jeff MacNelly.[81] The prize is awarded periodically to one German cartoonist and one North American cartoonist. Winners receive 1,300 Euros, a trip to Landau, and the Thomas Nast medal. The American advisory committee includes Nast's descendant Thomas Nast III of Fort Worth, Texas.[81] Other winners of the Thomas Nast Prize include Jim Borgman, Paul Szep, Pat Oliphant, David Levine, Jim Morin, and Tony Auth.[82]

"Nasty" does not come from Nast

The word "nasty" is erroneously thought to derive from Nast's name, due to the cynical tone of many of his cartoons.[83] In reality, the word's origins are unclear, but it is ancient, with written evidence that dates to the 1400s. Chief etymological theories prominently include derivation from Old Norse, Old French and/or some relation to a Dutch term.[84]

Notes

- ^ Nast believed his birthday was September 27, but his birth certificate issued under the auspices of the King of Bavaria, shows September 26. Adler, John. "About Nast". ThomasNast.com. Retrieved 2022-10-02.

- ^ "The Historic Elephant and Donkey; It Was Thomas Nast "Father of the American Cartoon," Who Brought Them Into Politics" (PDF). The New York Times. August 2, 1908. p. SM9. Retrieved 2017-09-20.

- ^ Dewey 2007, pp.14-18

- ^ "Timeline of Thomas Nast's Life".

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 7.

- ^ Adler, John. "About Nast". ThomasNast.com. Retrieved 2022-10-02.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c d e Bryant, Edward. "Nast, Thomas". In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ Halloran 2012, p. 3.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. v, 20.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 29.

- ^ Halloran 2012, p. 26.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 36.

- ^ Halloran 2012, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 84.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 98.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 69.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 112.

- ^ Halloran 2012, p. 102; Paine 1974, p. 135.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Worth, Richard (1998). Thomas Nast: Honesty in the Pursuit of Corruption. Las Cruces, NM: Sofwest Press. p. 40.

- ^ Halloran 2012, p. 197.

- ^ "Family Search.org" Link text

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 14.

- ^ Halloran 2012, p. 33.

- ^ Benjamin Justice, "Thomas Nast and the Public School of the 1870s". History of Education Quarterly 45#2 (2005): 171–206 [www.jstor.org/stable/20461949 in JSTOR].

- ^ Halloran 2012, pp. 32–35.

- ^ a b Halloran 2012, p. 35.

- ^ Halloran 2012, p. 34.

- ^ American Heritage August 1958 Volume IX Number 5 p. 90. The Nast cartoon of Charles Adams' 1876 campaign for governor is seen here.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. 148, 412.

- ^ Nast, Thomas (September 24, 1874). "Worse Than Slavery". Harper's Weekly. Vol. 18, no. 930. p. 878. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ a b Keller, Morton, "The World of Thomas Nast". Retrieved February 24, 2018.

- ^ Davies, Ross E. (January 10, 2011). "Thomas Nast's Illustrated Almanacs, 1871-1875". Greenbag Almanac Reader. 11 (4). Arlington: Antonin Scalia Law School, Law & Economics Research Paper Series: 212–220.

- ^ Nast's Illustrated Almanac (1871–1875) (reprinted in the 2011 Green Bag Almanac & Reader, pages 106-746).

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 204.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 140.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. 174–177.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. 145, 147, 158, 178.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 181.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Shirley, David (1998). Thomas Nast: Cartoonist and Illustrator. New York: Franklin Watts. p. 51.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. 336–337.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert C. (November 2001). "Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner, Artist: Thomas Nast". On This Day: HarpWeek. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on November 23, 2001. Retrieved November 23, 2001.

- ^ Walfred, Michele (July 2014). "Uncle Sam's Thanksgiving Dinner: Two Coasts, Two Perspectives". Thomas Nast Cartoons. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ^ Adler, John (2022). America's Most Influential Journalist: The Life, Times and Legacy of Thomas Nast. Harpweek Press. pp. iii. ISBN 978-0578294544.

- ^ Adler, John (2022). America's Most Influential Journalist: The Life, Times and Legacy of Thomas Nast. Harpweek Press. pp. xi. ISBN 978-0-578-29454-4.

- ^ Vinson, John C. Thomas Nast, Political Cartoonist. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1967.

- ^ Gerry, Margarita S. (2004) Through Five Administrations: Reminiscences of Colonel William H. Crook Body Guard to President Lincoln. Kessinger Publishing. p. 192. ISBN 1417960795.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 263.

- ^ Halloran 2012, p. 190.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. 283–285.

- ^ Halloran 2012, p. 188.

- ^ United States, Diane K. Skvarla, and Donald A. Ritchie (2006). United States Senate Catalogue of Graphic Art. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 329. ISBN 0160728533.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. 334–335, 349.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 349.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 352.

- ^ Halloran 2012, pp. 228–229.

- ^ a b Halloran 2012, p. 228.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. 216–218.

- ^ Halloran 2012, pp. 228–230.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. 412–413

- ^ Halloran 2012, p. 248.

- ^ Halloran 2012, pp. 250–252.

- ^ Halloran 2012, p. 255; Paine 1974, p. 480.

- ^ Nast & St. Hill 1974, p. 33.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 528

- ^ Halloran 2012, p. 270.

- ^ Paine 1974, pp. 510, 530.

- ^ Halloran 2012, pp. 266, 271.

- ^ Halloran 2012, p. 272.

- ^ Paine 1974, p. 540, Halloran 2012, p. 275.

- ^ a b c Halloran 2012, p. 278.

- ^ Forbes, Bruce D. (2008). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0520258020.

- ^ Rodibaugh, Jennifer J. (Spring–Summer 2008). "Cartoonery: When Donkey and Elephant First Clashed". American Heritage. 58 (4). Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Voorhees, Donal A. (1998). The Book of Totally Useless Information. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Haddon, Heather (December 14, 2011). "Cartoonist Draws Ire of N.J. Irish". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ a b "Editorial Cartooning Award Winners". editorialcartoonists.com. The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ^ a b "Nate Beeler Wins Thomas Nast Award; Bill Day Wins RFK Journalism Award". The Comics Reporter. Tom Spurgeon. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

The Thomas Nast Award has been part of the OPC Awards since 1968; past winners include Don Wright and Jim Morin.

Overseas Press Club of American website. Accessed Sept. 7, 2015. - ^ "OPC Renames Commentary and Cartoon Awards; Honors Flora Lewis". OPC. 2018-12-17. Retrieved 2019-01-01.

- ^ a b "The 2002 Thomas Nast Prize for editorial cartooning". editorialcartoonists.com (Press release). The Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. February 18, 2002. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ "Thomas Nast Prize". Witty World: International Cartoon Center. September 7, 2015 – via joeszabo.us.

- ^ Flippo, Hyde (March 6, 2017). "German Misnomers, Myths, and Mistakes: What's True and What's Not?". german.about.com. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (November 2001). "nasty etymology". etymonline.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

References and further reading

- Adler, John, and Draper Hill. Doomed by Cartoon: How Cartoonist Thomas Nast and the New York Times Brought Down Boss Tweed and His Ring of Thieves (Morgan James Publishing, 2008) online.

- Barrett, Ross. "On Forgetting: Thomas Nast, the Middle Class, and the Visual Culture of the Draft Riots." Prospects. 29 (2005): 25-55. online

- Boime, Albert. "Thomas Nast and French Art," American Art Journal. 4#1 (1972), pp. 43–65 in JSTOR

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 251.

- Dewey, Donald. The Art of Ill Will: The Story of American Political Cartoons. (NYU Press, 2007). ISBN 0814719856 online

- Halloran, Fiona Deans (2012). Thomas Nast: The Father of Modern Political Cartoons. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807835876. Scholarly biography online

- Orr, Brooke Speer. "Crusading Cartoonist: Thomas Nast, Reviews in American History (2014) 42#2 pp 292–95; review of Halloran (2012)

- Jarman, Baird. "The Graphic Art of Thomas Nast: Politics and Propriety in Postbellum Publishing." American Periodicals 20.2 (2010): 156-189. online

- Pflueger, Lynda. Thomas Nast: political cartoonist (2000), for middle schools online

- Vinson, John Chalmers. Thomas Nast: political cartoonist (University of Georgia Press, 2014).

- Wilde, Lukas RA, and Shane Denson. "Historicizing and Theorizing Pre-Narrative Figures—Who is Uncle Sam?." Narrative 30.2 (2022): 152-168. online

- Worth, Richard. Thomas Nast : honesty in the pursuit of corruption (1998) online. for secondary schools

Primary sources

- Nast, T., & St. Hill, T. N. (1974). Thomas Nast: Cartoons and Illustrations. (New York: Dover Publications) ISBN 0-486-23067-8 online

- Paine Albert Bigelow (1904). Th. Nast: His Period And His Pictures. New York: The MacMillan Company. Retrieved 2009-07-10. ISBN 0-87861-079-0 online

External links

- Official website

- Thomas Nast collection at Princeton University Library; 600 of Nast's original drawings and published wood engravings

- Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at Ohio State U.

- National History Day Project about Thomas Nast

- Elections 1860-1912 as covered by Harper's Weekly; news, editorials, cartoons (many by Nast)

- More work by Thomas Nast

- Nast cartoons focused on Chinese Exclusion. "Illustrating Chinese Exclusion"

- Thomas Nast Civil War Pictures

- Thomas Nast Caricatures of the Civil War, Reconstruction, Santa Claus, Napoleon, Catholicism, Boss Tweed, Tammany Hall and more.

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- Beach, Chandler B., ed. (1914). . . Chicago: F. E. Compton and Co.

- The Thomas Nast Collection--Morristown & Morris Township Public Library, NJ

- Thomas Nast on History Buff.

- "Emancipation," a work by Thomas Nast from 1865 via the World Digital Library

- Thomas Nast takes down Tammany: A cartoonist's crusade against a political boss from the Museum of the City of New York Collections blog

- The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum: Thomas Nast

- Works by Thomas Nast at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas Nast at the Internet Archive