Thunderbird (mythology)

| |

| Similar entities | Rain Bird, Pamola |

|---|---|

| Folklore | Indigenous peoples of the Americas |

| Region | North America |

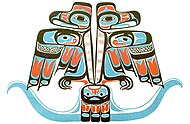

The thunderbird is a mythological bird-like spirit in North American indigenous peoples' history and culture. It is considered a supernatural being of power and strength.[1]

It is frequently depicted in the art, songs, and oral histories of many Pacific Northwest Coast cultures,[citation needed] but is also found in various forms among some peoples of the American Southwest,[citation needed] US East Coast,[citation needed] Great Lakes,[1] and Great Plains.[1]

Description

The thunderbird is said to create thunder by flapping its wings (Algonquian[2]), and lightning by flashing its eyes (Algonquian, Iroquois[3]). Across cultures, thunderbirds are generally depicted as birds of prey, or hybrids of humans and birds.[1] Thunderbirds are often viewed as protectors, sometimes intervening on people's behalf, but expecting veneration, prayers, and gifts.[1]

Archaeologically, sites containing depictions of thunderbirds have been found dating to the past 4,000 years.[1]

Petroglyphs of thunderbirds are found near Twin Bluffs, Wisconsin. They are in a shelter that was probably used c. 250 BCE to 1500.[4]

By people

Algonquian

The thunderbird myth and motif is prevalent among Algonquian peoples in the Northeast, i.e., Eastern Canada (Ontario, Quebec, and eastward) and Northeastern United States, and the Iroquois peoples (surrounding the Great Lakes).[5] The discussion of the Northeast region has included Algonquian-speaking people in the Lakes-bordering U.S. Midwest states (e.g., Ojibwe in Minnesota[6]).

In Algonquian mythology, the thunderbird controls the upper world while the underworld is governed by the underwater panther or Great Horned Serpent. The thunderbird creates not just thunder (with its wing-flapping) but lightning bolts, which it casts at the underworld creatures.[2]

Thunderbird in this tradition may be depicted as a spreadeagled bird (wings horizontal head in profile), but also quite common with the head facing forward, thus presenting an X-shaped appearance overall[6] (see under §Iconography below).

Ojibwe

The Ojibwe version of the myth states that the thunderbirds were created by Nanabozho to fight the underwater spirits. Thunderbirds also punished humans who broke moral rules. The thunderbirds lived in the four directions and arrived with the other birds in the springtime. In the fall, they migrated south after the end of the underwater spirits' most dangerous season.[7]

Menominee

The Menominee of Northern Wisconsin tell of a great mountain that floats in the western sky on which dwell the thunderbirds. They control the rain and hail, and delight in fighting and deeds of greatness. They are the enemies of the great horned snakes (the Misikinubik) and have prevented these from overrunning the earth and devouring humankind. They are messengers of the Great Sun himself.[8]

Siouan

The thunderbird motif is also seen in Siouan-speaking peoples, which include tribes traditionally occupying areas around the Great Lakes.

Ho-Chunk

Ho-Chunk tradition states that a man who has a vision of a thunderbird during a solitary fast will become a war chief of the people.[9]

Arikara

Ethnographer George Amos Dorsey transcribed a tale from the Arikaras with the title The Boy who befriended the Thunderbirds and the Serpent: a boy named Antelope-Carrier finds a nest with four young thunderbirds; their mother comes and tells the human boy that a two-headed Serpent comes out of the lake to eat the young.[10]

Iconography

X-shapes

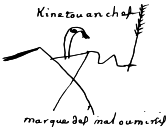

In Algonquian images, an X-shaped thunderbird is often used to depict the thunderbird with its wings alongside its body and the head facing forwards instead of in profile.[5]

The depiction may be stylized and simplified. A headless X-shaped thunderbird was found on an Ojibwe midewiwin disc dating to 1250–1400 CE.[11] In an 18th-century manuscript (a "daybook" ledger) written by the namesake grandson of Governor Matthew Mayhew, the thunderbird pictograms varies from "recognizable birds to simply an incised X".[12]

Non-indigenous scientific interpretations

American science historian and folklorist Adrienne Mayor and British historian Tom Holland have both suggested that indigenous thunderbird stories are based on discoveries of pterosaur fossils by Native Americans.[13][14]

Outside North America

Similar beings appear in mythologies the world over. Examples include the Chinese thunder-god Leigong, the Hindu Garuda and the African lightning bird.[15]

In popular culture

- The shoulder sleeve insignia for the 45th Infantry Division (Oklahoma Army National Guard) was a thunderbird patch after 1939.[16]

- Several X-Men characters go by the name Thunderbird, the first appearing in 1975.[17]

- The Ford Thunderbird is an American car.[18]

- A WWII-era airfield for pilot training in Arizona was called Thunderbird Field, which in turn was the inspiration for other names, including:

- The Thunderbird School of Global Management at Arizona State University.

- The 1960s TV show Thunderbirds created by Gerry Anderson.[19]

- In 1925, Aleuts were recorded as using the term to describe the Douglas World Cruiser aircraft which passed through Atka on the first aerial circumnavigation by a US Army team the previous year.[20]: 100

- The Pokémon Zapdos is based on First Nations folklore surrounding the Thunderbird.[21]

- Thunderbird is a roller coaster at Holiday World & Splashin' Safari in Santa Claus, Indiana.

- Mozilla Thunderbird is a free and open-source cross-platform email client.

- The Thunderbird is the cap badge and symbol of the Canadian Forces Military Police since 1968.

- Various sports teams are called the Thunderbirds or have Thunderbird mascots, including:

- The Seattle Thunderbirds of the Western Hockey League.

- The teams of Southern Utah University, in Cedar City, UT.

- The teams of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver campus.

- The Connetquot School District in Long Island, which was the subject of a lawsuit in 2023.[22]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f "Rulers of the Upper Realm, Thunderbirds Are Powerful Native Spirits". Audubon. 2020-11-30. Retrieved 2024-07-09.

- ^ a b Cleland, Chute & Haltiner (1984), p. 240

- ^ Lenik (2012), p. 163

- ^ "Rock Art - Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center". Mississippi Valley Archaeology Center. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ a b Lenik (2012), p. 163.

- ^ a b Lenik (2012), p. 181.

- ^ Vecsey, Christopher (1983). Traditional Ojibwa Religion and Its Historical Changes. Vol. 152. American Philosophical Society. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-87169-152-1.

- ^ Lankford, George E. (2011). Native American Legends of the Southeast: Tales from the Natchez, Caddo, Biloxi, Chickasaw, and other Nations. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-8173-5689-7.

- ^ Burlin, Nathalie C. (1907). The Indians' Book: An Offering by the American Indians of Indian Lore, Musical and Narrative, to Form a Record of the Songs and Legends of Their Race. Harper and Brothers.

- ^ Dorsey, George Amos. Traditions of the Arikara. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1904. pp. 73-79, 187.

- ^ Bouck & Richardson (2007), p. 15, citing Cleland (1984), p. 240, figure 2C; Lenik (1985), p. 132, figure 5.

- ^ Bouck & Richardson (2007), p. 15.

- ^ Mayor, Adrienne (2005). Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11345-9.

- ^ "BBC Four - Dinosaurs, Myths and Monsters".

- ^ Andrews, Tamra (2000). Dictionary of Nature Myths: Legends of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. Oxford University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-19-513677-7.

- ^ Whitlock, Flint (16 April 1998). The Rock Of Anzio: From Sicily To Dachau: A History Of The U.s. 45th Infantry Division. Basic Books. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-8133-3399-1.

- ^ Doran, Michael (28 April 2022). "Thunderbird is back and badass after 50 years in Giant-Size X-Men special". GamesRadar+. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ Bacon, Roy (2000). The Ford Thunderbird. Gramercy Books. ISBN 978-0-517-16173-9.

- ^ Gerry Anderson – The Authorised Biography, by Simon Archer & Stan Nicholls, 1996, pp. 85–86, ISBN 0-09-978141-7.

- ^ Thomas, Lowell (1925). The First World Flight. Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ^ "17 Pokemon based on real-world mythology". 4 February 2014.

- ^ "Connetquot schools sue Regents over Native American mascot ban". Newsday. 2023-10-19. Retrieved 2024-06-19.

Sources

- Bouck, Jill; Richardson, James B. III (2007). "Enduring Icon: A Wampanoag Thunderbird on an Eighteenth Century English Manuscript From Martha's Vineyard". Archaeology of Eastern North America. 35: 11–19. JSTOR 40914506.

- Cleland, Charles E.; Chute, Richard D.; Haltiner, Robert E. (1984). "NAUB-COW-ZO-WIN Discs from Northern Michigan". Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology. 9 (2): 235–249. JSTOR 20707933.

- Lenik, Edward J. (2012). "The Thunderbird Motif in Northeastern Indian Art". Archaeology of Eastern North America. 40: 163–185. JSTOR 23265141.

External links

Media related to Thunderbird (mythology) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Thunderbird (mythology) at Wikimedia Commons