Uterine tube

| Fallopian tube | |

|---|---|

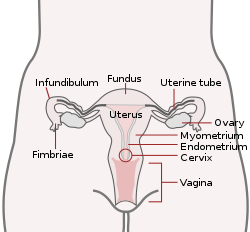

Uterus and fallopian tubes labelled as uterine tubes | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Paramesonephric ducts |

| System | Reproductive system |

| Artery | Tubal branches of ovarian artery, tubal branch of uterine artery via mesosalpinx |

| Lymph | Lumbar lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tuba uterina |

| Greek | σάλπιγξ (sálpinx) |

| MeSH | D005187 |

| TA98 | A09.1.02.001 |

| TA2 | 3486 |

| FMA | 18245 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The fallopian tubes, also known as uterine tubes, oviducts[1] or salpinges (sg.: salpinx), are paired tubular sex organs in the human female body that stretch from the ovaries to the uterus. The fallopian tubes are part of the female reproductive system. In other vertebrates, they are only called oviducts.[2]

Each tube is a muscular hollow organ[3] that is on average between 10 and 14 cm (3.9 and 5.5 in) in length, with an external diameter of 1 cm (0.39 in).[4] It has four described parts: the intramural part, isthmus, ampulla, and infundibulum with associated fimbriae. Each tube has two openings: a proximal opening nearest to the uterus, and a distal opening nearest to the ovary. The fallopian tubes are held in place by the mesosalpinx, a part of the broad ligament mesentery that wraps around the tubes. Another part of the broad ligament, the mesovarium suspends the ovaries in place.[5]

An egg cell is transported from an ovary to a fallopian tube where it may be fertilized in the ampulla of the tube. The fallopian tubes are lined with simple columnar epithelium with hairlike extensions called cilia, which together with peristaltic contractions from the muscular layer, move the fertilized egg (zygote) along the tube. On its journey to the uterus, the zygote undergoes cell divisions that changes it to a blastocyst, an early embryo, in readiness for implantation.[6]

Almost a third of cases of infertility are caused by fallopian tube pathologies. These include inflammation, and tubal obstructions. A number of tubal pathologies cause damage to the cilia of the tube, which can impede movement of the sperm or egg.[7]

The name comes from the Italian Catholic priest and anatomist Gabriele Falloppio, for whom other anatomical structures are also named.[8]

Structure

Each fallopian tube leaves the uterus at an opening at the uterine horns known as the proximal tubal opening or proximal ostium.[9] The tubes have an average length of 10–14 centimeters (3.9–5.5 in)[4] that includes the intramural part of the tube. The tubes extend to near the ovaries where they open into the abdomen at the distal tubal openings. In other mammals, the fallopian tube is called the oviduct, which may also be used in reference to the fallopian tube in the human.[10][11] The fallopian tubes are held in place by the mesosalpinx a part of the broad ligament mesentery that wraps around the tubes. Another part of the broad ligament, the mesovarium suspends the ovaries in place.[5]

Parts

Each tube is composed of four parts: from inside the proximal tubal opening the intramural or interstitial part, that links to the narrow isthmus, the isthmus connects to the larger ampulla, which connects with the infundibulum and its associated fimbriae that opens into the peritoneal cavity from the distal tubal opening.[12]

Intramural part

The intramural part or interstitial part of the fallopian tube lies in the myometrium, the muscular wall of the uterus. This is the narrowest part of the tube that crosses the uterus wall to connect with the isthmus. The intramural part is 0.7 mm wide and 1 cm long.[12]

Isthmus

The narrow isthmus links the tube to the uterus, and connects to the ampulla. The isthmus is a rounded, and firm muscular part of the tube. The isthmus is 1–5 mm wide, and 3 cm long.[12] The isthmus contains a large number of secretory cells.[10]

Ampulla

The ampulla is the major part of the fallopian tube. The ampulla is the widest part of the tube with a maximal luminal diameter of 1 cm, and a length of 5 cm. It curves over the ovary, and is the primary site of fertilization.[12] The ampulla contains a large number of ciliated epithelial cells.[10] It is thin walled with a much folded luminal surface, and opens into the infundibulum.[12]

Infundibulum

The infundibulum opens into the abdomen at the distal tubal opening and rests above the ovary. Most cells here are ciliated epithelial cells.[10] The opening is surrounded by fimbriae, which help in the collection of the oocyte after ovulation.[4] The fimbriae (singular fimbria) is a fringe of densely ciliated tissue projections of approximately 1 mm in width around the distal tubal opening, oriented towards the ovary.[12] They are attached to the ends of the infundibulum, extending from its inner circumference, and muscular wall.[12] The cilia beat towards the fallopian tube.[12] Of all the fimbriae, one fimbria known as the ovarian fimbria is long enough to reach and make contact with the near part of the ovary during ovulation.[13][14][12] The fimbriae have a higher density of blood vessels than the other parts of the tube, and the ovarian fimbria is seen to have an even higher density.[8]

An ovary is not directly connected to its adjacent fallopian tube. When ovulation is about to occur, the sex hormones activate the fimbriae,[citation needed] causing them to swell with blood, extend, and hit the ovary in a gentle, sweeping motion. An oocyte is released from the ovary into the peritoneal cavity and the cilia of the fimbriae sweep it into the fallopian tube.

Microanatomy

When viewed under the microscope, the fallopian tube has three layers.[6] From outer to inner, these are the serosa, muscularis mucosae, and the mucosa.[15][16]

The outermost covering layer of serous membrane is known as the serosa.[6] The serosa is derived from the visceral peritoneum.[14]

The muscularis mucosae consists of an outer ring of smooth muscle arranged longitudinally, and a thick inner circular ring of smooth muscle.[6] This layer is responsible for the rhythmic peristaltic contractions of the fallopian tubes, that with the cilia move the egg cell towards the uterus.[14]

The innermost mucosa is made up of a layer of luminal epithelium, and an underlying thin layer of loose connective tissue the lamina propria.[16] There are three different cell types in the epithelium. Around 25% of the cells are ciliated columnar cells; around 60% are secretory cells, and the rest are peg cells thought to be a secretory cell variant.[4] The ciliated cells are most numerous in the infundibulum, and the ampulla. Estrogen increases the formation of cilia on these cells. Peg cells are shorter, have surface microvilli, and are located between the other epithelial cells.[6] The presence of immune cells in the mucosa has also been reported with the main type being CD8+ T-cells. Other cells found are B lymphocytes, macrophages, NK cells, and dendritic cells.[16]

The histological features of tube vary along its length. The mucosa of the ampulla contains an extensive array of complex folds, whereas the relatively narrow isthmus has a thick muscular coat and simple mucosal folds.[14]

Development

Embryos develop a genital ridge that forms at their tail end and eventually forms the basis for the urinary system and reproductive tracts. Either side and to the front of this tract, around the sixth week develops a duct called the paramesonephric duct, also called the Müllerian duct.[17] A second duct, the mesonephric duct, develops adjacent to this. Both ducts become longer over the next two weeks, and the paramesonephric ducts around the eighth week cross to meet in the midline and fuse.[17] One duct then regresses, with this depending on whether the embryo is genetically female or male. In females, the paramesonephric duct remains, and eventually forms the female reproductive tract.[17] The portions of the paramesonephric duct, which are more cranial—that is, further from the tail-end, end up forming the fallopian tubes.[17] In males, because of the presence of the Y sex chromosome, anti-Müllerian hormone is produced. This leads to the degeneration of the paramesonephric duct.[17]

As the uterus develops, the part of the fallopian tubes closer to the uterus, the ampulla, becomes larger. Extensions from the fallopian tubes, the fimbriae, develop over time. Cell markers have been identified in the fimbriae, which suggests that their embryonic origin is different from that of the other tube segments.[8]

Apart from the presence of sex chromosomes, specific genes associated with the development of the fallopian tubes include the Wnt and Hox groups of genes, Lim1, Pax2, and Emx2.[17]

Embryos have two pairs of ducts that will let gametes out of the body when they are adults; the Müllerian ducts develop in females into the fallopian tubes, uterus, and vagina.

Function

Fertilization

The fallopian tube allows the passage of an egg from the ovary to the uterus. When an oocyte is developing in an ovary, it is surrounded by a spherical collection of cells known as an ovarian follicle. Just before ovulation, the primary oocyte completes meiosis I to form the first polar body and a secondary oocyte, which is arrested in metaphase of meiosis II.

At the time of ovulation in the menstrual cycle, the secondary oocyte is released from the ovary. The follicle and the ovary's wall rupture, allowing the secondary oocyte to escape. The secondary oocyte is caught by the fimbriated end of the fallopian tube and travels to the ampulla. Here, the egg is able to become fertilized with sperm. The ampulla is typically where the sperm are met and fertilization occurs; meiosis II is promptly completed. After fertilization, the ovum is now called a zygote and travels toward the uterus with the aid of the hairlike cilia and the activity of the muscle of the fallopian tube. The early embryo requires critical development in the fallopian tube.[10] After about five days, the new embryo enters the uterine cavity and, on about the sixth day, begins to implant on the wall of the uterus.

The release of an oocyte does not alternate between the two ovaries and seems to be random. After removal of an ovary, the remaining one produces an egg every month.[18]

Clinical significance

Almost a third of cases of infertility are caused by fallopian tube pathologies. These include inflammation, and tubal obstructions. A number of tubal pathologies cause damage to the cilia of the tube, which can impede movement of the sperm or egg. A number of sexually transmitted infections can lead to infertility.[7]

Inflammation

Salpingitis is inflammation of the fallopian tubes and may be found alone, or with other pelvic inflammatory diseases (PIDs). A thickening of the fallopian tube at its narrow isthmus portion, due to inflammation, is known as salpingitis isthmica nodosa. Like another PID endometriosis, it may lead to fallopian tube obstruction. Fallopian tube obstruction may be a cause of infertility or ectopic pregnancy.[19]

Blockage or narrowing

If a blocked fallopian tube has affected fertility, its repair where possible may increase the chances of becoming pregnant.[20] Tubal obstruction can be proximal, distal or mid-segmental. Tubal obstruction is a major cause of infertility but full testing of tubal functions is not possible. However, the testing of patency – whether or not the tubes are open can be carried out using hysterosalpingography, laparoscopy and dye, or hystero contrast sonography (HyCoSy). During surgery, the condition of the tubes may be inspected and a dye such as methylene blue can be injected into the uterus and shown to pass through the tubes when the cervix is occluded. As tubal disease is often related to Chlamydia infection, testing for Chlamydia antibodies has become a cost-effective screening device for tubal pathology.[21]

Ectopic pregnancy

Occasionally the embryo implants outside of the uterus, creating an ectopic pregnancy. Most ectopic pregnancies occur in the fallopian tube, and are commonly known as tubal pregnancies.[22]

Surgery

The surgical removal of a fallopian tube is called a salpingectomy. To remove both tubes is a bilateral salpingectomy. An operation that combines the removal of a fallopian tube with the removal of at least one ovary is a salpingo-oophorectomy. An operation to remove a fallopian tube obstruction is called a tuboplasty. A surgical procedure to permanently prevent conception is tubal ligation.

Cancer

Fallopian tube cancer, which typically arises from the epithelial lining of the fallopian tube, has historically been considered to be a very rare malignancy. Evidence suggests it probably represents a significant portion of what has previously been classified as ovarian cancer, as much as 80 per cent. These are classed as serous carcinomas, and are usually located in the fimbriated distal tube.[23]

Other

In rare cases, a fallopian tube may prolapse into the vaginal canal following a hysterectomy. The swollen fimbriae can have the appearance of an adenocarcinoma.[24]

History

The Greek doctor Herophilus, in his treatise on midwifery, points out the existence of the two ducts that he supposed transported "female semen". Then Galen, already in the modern era, described that the paired ducts indicated by Herophilus were connected to the uterus.

In 1561, the Renaissance doctor Gabriele Falloppio published his book Observationes Anatomicae. Its contribution is a detailed description of the "tubal" of the uterus and its different portions, with its farthest (distal) end open towards the abdomen, and the other (proximal) connected to the uterus.[25][26]

Though the name Fallopian tube is eponymous, it is often spelt with a lower case f from the assumption that the adjective fallopian has been absorbed into modern English as the de facto name for the structure. Merriam-Webster dictionary for example lists fallopian tube, often spelt Fallopian tube.[27]

Additional images

-

Image showing numbered parts of the fallopian tubes and surrounding structures

-

Female reproductive system numbered parts

-

Image showing the right fallopian tube (here labeled the uterine tube) seen from behind. The uterus, ovaries and right broad ligament are labeled.

-

Cross-section of fallopian tube, stained and viewed under microscope

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1257 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1257 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ "Uterine Tube (Fallopian Tube) Anatomy: Overview, Pathophysiological Variants". 14 July 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ Zhao, W; Zhu, Q; Yan, M; Li, C; Yuan, J; Qin, G; Zhang, J (February 2015). "Levonorgestrel decreases cilia beat frequency of human fallopian tubes and rat oviducts without changing morphological structure". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 42 (2): 171–8. doi:10.1111/1440-1681.12337. PMC 6680194. PMID 25399777.

- ^ Han, Joan; Sadiq, Nazia M. (2022). "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Fallopian Tube". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31613440. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Fallopian Tube Disorders: Overview, Salpingitis and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease, Salpingitis Isthmica Nodosa". 15 March 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ a b Craig, Morgan E.; Sudanagunta, Sneha; Billow, Megan (2022). "Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Broad Ligaments". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29763118. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Tortora, Gerard J. (2010). Principles of anatomy and physiology (12th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 1103. ISBN 9780470233474.

- ^ a b Briceag I, Costache A, Purcarea VL, Cergan R, Dumitru M, Briceag I, Sajin M, Ispas AT (2015). "Fallopian tubes--literature review of anatomy and etiology in female infertility". J Med Life. 8 (2): 129–31. PMC 4392087. PMID 25866566.

- ^ a b c Castro PT, Aranda OL, Marchiori E, de Araújo LF, Alves HD, Lopes RT, Werner H, Araujo Júnior E (2020). "Proportional vascularization along the fallopian tubes and ovarian fimbria: assessment by confocal microtomography". Radiol Bras. 53 (3): 161–166. doi:10.1590/0100-3984.2019.0080. PMC 7302899. PMID 32587423.

- ^ Thurmond, Amy S.; Brandt, Kathleen R.; Gorrill, Marsha J. (March 1999). "Tubal Obstruction after Ligation Reversal Surgery: Results of Catheter Recanalization". Radiology. 210 (3): 747–750. doi:10.1148/radiology.210.3.r99mr10747. PMID 10207477. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Li, Shuai; Winuthayanon, Wipawee (January 2017). "Oviduct: roles in fertilization and early embryo development". The Journal of Endocrinology. 232 (1): R1 – R26. doi:10.1530/JOE-16-0302. PMID 27875265. S2CID 27164540.

- ^ Harris, Emily A.; Stephens, Kalli K.; Winuthayanon, Wipawee (5 November 2020). "Extracellular Vesicles and the Oviduct Function". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (21): 8280. doi:10.3390/ijms21218280. PMC 7663821. PMID 33167378.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Standring, Susan (2016). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (Forty-first ed.). [Philadelphia]. p. 1301. ISBN 9780702052309.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "ovarian fimbria". cancerweb.ncl.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d Daftary, Shirish; Chakravarti, Sudip (2011). Manual of Obstetrics (3rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1–16. ISBN 9788131225561.

- ^ "Dictionary - Normal: Fallopian tube - The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Rigby CH, Aljassim F, Powell SG, Wyatt JN, Hill CJ, Hapangama DK (August 2022). "The immune cell profile of human fallopian tubes in health and benign pathology: a systematic review". J Reprod Immunol. 152: 103646. doi:10.1016/j.jri.2022.103646. PMID 35644062.

- ^ a b c d e f Blaustein's pathology of the female genital tract (6th ed.). New York: Springer. 2011. pp. 530–531. ISBN 9781441904881.

- ^ McLaughlin, Jessica E. "Menstrual Cycle: Biology of the Female Reproductive System: Merck Manual Home Health Handbook". Merck Manual. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ Salpingitis at eMedicine

- ^ "Tubal Factor Infertility (Fallopian Tube Obstruction) | ColumbiaDoctors - New York". ColumbiaDoctors. 20 June 2017. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Kodaman, Pinar H.; Arici, Aydin; Seli, Emre (June 2004). "Evidence-based diagnosis and management of tubal factor infertility". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 16 (3): 221–229. doi:10.1097/00001703-200406000-00004. PMID 15129051. S2CID 43312882.

- ^ "Ectopic pregnancy | RCOG". Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ Berek JS, Renz M, Kehoe S, Kumar L, Friedlander M (October 2021). "Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: 2021 update". Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 155 (Suppl 1): 61–85. doi:10.1002/ijgo.13878. PMC 9298325. PMID 34669199.

- ^ Delmore, James E. (2008). "Benign Neoplasms of the Vagina". GLOWM. doi:10.3843/GLOWM.10005. ISSN 1756-2228. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ Godoy-Guzmán, C.; Fuentes, J. L.; Osses, M.; Toledo-Ordoñez, I.; Orihuela, P. (June 2018). "La Tuba Uterina: Desde Herófilo a Horacio Croxatto". International Journal of Morphology. 36 (2): 387–390. doi:10.4067/s0717-95022018000200387. ISSN 0717-9502.

- ^ Herrera Calmet, Abelardo (2 July 2015). "Cáncer primitivo de la trompa de falopio". Revista Peruana de Ginecología y Obstetricia. 3 (3): 172–182. doi:10.31403/rpgo.v3i1157. ISSN 2304-5132.

- ^ "Definition of FALLOPIAN TUBE". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

External links

- Histology image: 18501loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Menstrual Cycle - Merck