Ventrogluteal area

| Gluteal muscles | |

|---|---|

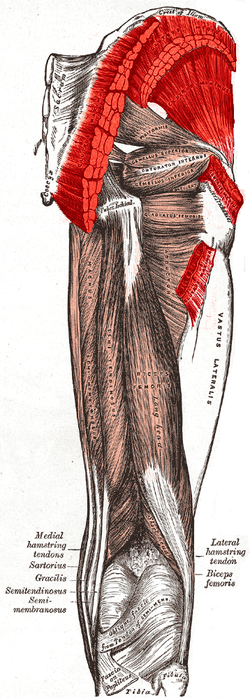

Right leg, Calves rear view: Muscles of the gluteal and posterior femoral regions. Gluteus minimus and the origins and insertions of medius and maximus shown in red & also lower legs | |

Gluteus maximus | |

| Details | |

| Parts | Gluteus maximus, gluteus medius and gluteus minimus |

| Artery | Superior and inferior gluteal arteries |

| Vein | Superior and inferior gluteal veins |

| Nerve | Superior and inferior gluteal nerves (L4, L5, S1 and S2 nerve roots) |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The gluteal muscles, often called glutes, are a group of three muscles which make up the gluteal region commonly known as the buttocks: the gluteus maximus, gluteus medius and gluteus minimus. The three muscles originate from the ilium and sacrum and insert on the femur. The functions of the muscles include extension, abduction, external rotation, and internal rotation of the hip joint.[1]

Structure

The gluteus maximus is the largest and most superficial of the three gluteal muscles. It makes up a large part of the shape and appearance of the hips. It is a narrow and thick fleshy mass of a quadrilateral shape, and forms the prominence of the buttocks. The gluteus medius is a broad, thick, radiating muscle, situated on the outer surface of the pelvis. It lies profound to the gluteus maximus and its posterior third is covered by the gluteus maximus, its anterior two-thirds by the gluteal aponeurosis, which separates it from the superficial fascia and skin. The gluteus minimus is the smallest of the three gluteal muscles and is situated immediately beneath the gluteus medius.

The bulk of the gluteal muscle mass contributes only partially to shape of the buttocks. The other major contributing factor is that of the panniculus adiposus (fatty layer) of the buttocks, which is very well developed in this area, and gives the buttock its characteristic rounded shape. Exercise in general (not only of the gluteal muscles but of the body in general) which can contribute to fat loss can lead to reduction of mass in subcutaneal fat storage locations on the body which includes the panniculus, so for leaner and more active individuals, the glutes will more predominantly contribute to the shape than someone less active with a fattier composition.[citation needed] The degree of body fat stored in various locations such as the panniculus is dictated by genetic and hormonal profiles.[citation needed]

Gluteus maximus

The gluteus maximus arises from the posterior gluteal line of the inner upper ilium, and the rough portion of bone including the crest, immediately above and behind it; from the posterior surface of the lower part of the sacrum and the side of the coccyx; from the aponeurosis of the erector spinae (lumbodorsal fascia), the sacrotuberous ligament, and the fascia covering the gluteus medius. The fibers are directed obliquely downward and lateralward; the muscle has two insertions: Those forming the upper and larger portion of the muscle, together with the superficial fibers of the lower portion, end in a thick tendinous lamina, which passes across the greater trochanter, and inserts into the iliotibial band of the fascia lata; and the deeper fibers of the lower portion of the muscle are inserted into the gluteal tuberosity between the vastus lateralis and adductor magnus. Its action is to extend and to laterally rotate the hip, and also to extend the trunk.

The gluteus maximus is larger in size and thicker in humans than in other primates.[2] Specifically, it is approximately 1.6 times larger relative to body mass compared to chimpanzees and comprises about 18.3% of total hip musculature mass versus 11.7% in chimpanzees.[3]

Gluteus medius

The gluteus medius muscle originates on the outer surface of the ilium between the iliac crest and the posterior gluteal line above, and the anterior gluteal line below; the gluteus medius also originates from the gluteal aponeurosis that covers its outer surface. The fibers of the muscle converge into a strong flattened tendon that inserts on the lateral surface of the greater trochanter. More specifically, the muscle's tendon inserts into an oblique ridge that runs downward and forward on the lateral surface of the greater trochanter.

Gluteus minimus

The gluteus minimus is fan-shaped, arising from the outer surface of the ilium, between the anterior and inferior gluteal lines, and behind, from the margin of the greater sciatic notch. The fibers converge to the deep surface of a radiated aponeurosis, and this ends in a tendon which is inserted into an impression on the anterior border of the greater trochanter, and gives an expansion to the capsule of the hip joint.

Function

The functions of muscles includes extension, abduction and internal as well as external rotation of the hip joint. The gluteus maximus also supports the extended knee through the iliotibial tract.

The human gluteus maximus plays multiple important functional roles, particularly in running rather than walking. During running, it helps control trunk flexion, aids in decelerating the swing leg, and contributes to hip extension. During level walking, the muscle shows minimal activity, suggesting its enlargement was not primarily adapted for walking.[4][3]

The muscle's size and position make it uniquely suited for controlling trunk position during rapid movements and stabilizing the trunk against flexion. While traditionally associated with maintaining erect posture, evidence suggests its enlargement was more likely selected for its role in running capability and trunk stabilization during various dynamic activities. These adaptations would have been particularly important for activities like running and climbing in early human evolution.[3]

Clinical significance

Sitting for long periods can lead to the gluteal muscles atrophying through constant pressure and disuse. This may be associated with (although not necessarily the cause of) lower back pain, difficulty with some movements that naturally require the gluteal muscles such as rising from the seated position, and climbing stairs.

Exercise and stretching

Any exercise that works and/or stretches the buttocks is suitable, for example lunges, hip thrusts, climbing stairs, fencing, bicycling, rowing, squats, arabesque, aerobics, and various specific exercises for the bottom. Weight training exercises which are known to significantly strengthen the gluteal muscles include the squat, deadlift, leg press, any other movements involving external hip rotation and hip extension.

Society and culture

Cultural significance

Well formed gluteal muscles have long been associated with health, strength and sexual attractiveness. In terms of health, they act as a sign of 'being in shape'. This usually means a person is also eating, sleeping and exercising properly, all of which are beneficial to health. In terms of strength, the glutes are among the largest and most powerful muscles in the body. If they are well developed then a person is more likely to be strong. They are also key contributors to movement ranges of fundamental importance, such as bending and straightening the legs, and bending, straightening and twisting at the waist. These movement ranges are key in a person's ability to move in a powerful, dynamic fashion and they are powered to a significant extent by the glutes. If they are well formed then a person is much more likely to be able to move efficiently. In terms of sexual attractiveness, the glute specialist Bret Contreras considers in physio-anthropological terms that this is based upon a sub-conscious assessment of the relationship between a physical capability to survive and prosper, and the ability to raise a family.[5]

'It stands to reason that both males and females were attracted to nice glutes, instinctively making the connection to big, strong glutes and survival, reproduction, hunting and protection.'[6]

Artistic representation

Prominent gluteal muscles are often used in art in order to imply an ability to move in a powerful, dynamic fashion; virility and fertility; and to meet aesthetic considerations in these regards.

- Artistic representations of the gluteal muscles

-

The Venus Callipyge statue, 1st or 2nd Century B.C.

-

An Ancient Greek athlete using a strigil, which is a device used for cleaning off oil and dirt

-

Ancient Greek sprinters, c. 530 B.C.

-

Pankratiasts fighting on a Roman relief

-

The large glutes and muscular proportions of this heavyweight boxer demonstrate the 20th Century revival of historical training focuses

-

Modern sprinters, 2017

-

A pole vaulter, 2019

-

The commercialisation of the gluteal muscles as demonstrated by an adult entertainment associate, 2014

See also

Additional images

-

Position of gluteus maximus muscle

-

Position of gluteus medius muscle

-

Position of gluteus minimus muscle

References

- ^ Moore, Keith L.; Dalley II, Arthur F.; Agur, Anne M. R. (2018). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (Eighth ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer. pp. 722–723. ISBN 9781496347213.

- ^ Standring, Susan, ed. (2016). "Pelvic girdle, gluteal region and thigh: Gluteus maximus". Gray's anatomy: The anatomical basis of clinical practice (41st ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Limited. pp. 1357–1358. ISBN 9780702052309. OCLC 920806541.

- ^ a b c Lieberman, Daniel E.; Raichlen, David A.; Pontzer, Herman; Bramble, Dennis M.; Cutright-Smith, Elizabeth (2006). "The human gluteus maximus and its role in running". Journal of Experimental Biology. 209 (11): 2143–2155. doi:10.1242/jeb.02255. ISSN 1477-9145.

- ^ Niinimäki, Sirpa; Härkönen, Laura; Nikander, Riku; Abe, Shinya; Knüsel, Christopher; Sievänen, Harri (2016). "The cross-sectional area of the gluteus maximus muscle varies according to habitual exercise loading: Implications for activity-related and evolutionary studies". HOMO. 67 (2): 125–137. doi:10.1016/j.jchb.2015.06.005.

- ^ Bret Contreras, Glen Cordoza (2019). The Glute Lab. Victory Belt Publishing. pp. 5, 25. ISBN 9781628603460.

- ^ Bret Contreras, Glen Cordoza (2019). The Glute Lab. Victory Belt Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 9781628603460.

- McMinn, RMH (Ed) (1994) Last's Anatomy: Regional and applied (9th Ed). London: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 0-443-04662-X

External links

- 8b. The Muscles and Fasciæ of the Thigh Bartleby.com, Henry Gray, Anatomy of the Human Body, 1918.