Viking raid on Seville (844)

| Viking raid on Išbīliya | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Viking expansion | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Vikings of Noirmoutier, Francia[1] |

Emirate of Cordoba Banu Qasi | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Unknown |

Isa ibn Shuhayd Musa ibn Musa al-Qasi Abd al-Wāḥid ben Yazīd al-Iskandarānī[2] | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Early Muslim accounts: 16,000 men 80 ships[3][4] | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Early Muslim accounts: 500–1,000 killed 30 ships destroyed[5][6] | Unknown | ||||||

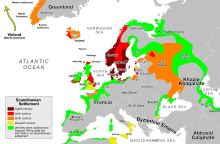

The Viking raid on Išbīliya, then part of the Umayyad Emirate of Córdoba, took place in 844. After raiding the coasts of what are now Spain and Portugal, a Viking fleet arrived in Išbīliya (now Seville) through the Guadalquivir on 25 September and took the city on 1 or 3 October. The Vikings pillaged the city and the surrounding areas. Emir Abd ar-Rahman II of Córdoba mobilized and sent a large force against the Vikings under the command of the hajib (chief-minister) Isa ibn Shuhayd. After a series of indecisive engagements, the Muslim army defeated the Vikings on either 11 or 17 November. Seville was retaken and the remnants of the Vikings fled Spain. After the raid, the Muslims raised new troops and built more ships and other military equipment to protect the coast. The quick military response in 844 and the subsequent defensive improvements discouraged further attacks by the Vikings.[3]

Historians such as Hugh N. Kennedy and Neil Price contrast the rapid Muslim response during the 844 raids, as well as the organization of long-term defenses, with the weak responses by the Carolingian dynasty and Anglo-Saxons against Viking aggression.[3][7]

Background

After the Abbasid Revolution which overthrew the Umayyad Caliphate, Muslims of the Iberian Peninsula (called al-Andalus by the Muslims) declared an independent emirate, with its capital in Córdoba in 756.[8] The Umayyad-ruled emirate received waves of refugees who escaped the revolution in the Middle East, and soon became a center of intellectual development.[8] The 844 raid was the first confirmed large-scale Viking incursion on the peninsula.[8] During this period, al-Andalus was in a state of uneasy peace with the Iberian and Frankish Christians to its north, dotted by constant skirmishes and occasional military campaigns across a sort of a demilitarized zone between them.[8] There might have been small Viking incursions to the Kingdom of Asturias in the early ninth century prior to the raid.[8]

Before the raid

The Viking fleet was, prior to attacking Seville, seen near the coast of France and on French rivers (the Seine, the Loire, and the Garonne).[9] They plundered Asturias, under the rule of the Christian King Ramiro I, but suffered heavy losses at A Coruña and were defeated by Ramiro at the Tower of Hercules. Next, they sailed southward and plundered the Atlantic coast. They took the Muslim city of Lisbon in August or September 844[a] and occupied it for 13 days, during which time they engaged in skirmishes with the Muslims.[11][12] The governor of Lisbon, Wahballah ibn Hazm, wrote about the attack to Emir Abd ar-Rahman II of Córdoba, who was the overall leader of Muslims in Spain.[13][3] After leaving Lisbon, they sailed further south and raided the Spanish towns of Cadiz, Medina Sidonia, and Algeciras, and possibly the Abbasid-controlled town of Asilah in modern-day Morocco.[6]

Raid and reconquest

On 25 September, the Vikings arrived near Seville after sailing up the Guadalquivir.[6] They set up their base on Isla Menor, a defensible island on the Guadalquivir Marshes.[6] On 29 September, local Muslim forces marched against the Vikings but were defeated.[12] The Vikings took Seville by storm on 1 or 3 October after a brief siege and heavy fighting.[12][13][6][11] They looted and pillaged the city, and, according to Muslim historians, gave its inhabitants the "terrors of imprisonment or death" and spared "not even the beasts of burden".[3][12][13] Although the unwalled city of Seville was taken, its citadel remained in Muslim hands.[11] The Vikings tried but failed to burn the city's recently built great mosque.[14]

When he heard about the fall of Seville, Abd ar-Rahman II mobilized his forces under the leadership of his hajib, Isa ibn Shuhayd.[13] He summoned nearby governors to gather their men.[13] They assembled in Córdoba, and then marched to Axarafe, a hill near Seville, where Isa ibn Shuhayd set up his headquarters.[13] A contingent led by Musa ibn Musa al-Qasi, the leader of the semi-independent Banu Qasi principality to the north, joined this army despite Musa ibn Musa's political rivalry with Abd ar-Rahman and played an important part in the campaign.[3][15]

In the following days, the two sides clashed multiple times, with varying results.[5][11] Finally the Muslims won a major victory on 11 or 17 November at Talyata.[11][5][16] According to Muslim sources, 500 to 1000 Vikings were killed and 30 Viking ships were destroyed.[5][6] (The Muslims made use of Greek fire, an incendiary liquid thrown by catapults, to burn the invaders' ships.[6]) The Muslims also reported that the commanders of the Vikings were killed and at least 400 were captured – many of whom were hanged from the palm-trees of Talyata.[6][5] The remaining Vikings retreated to their vessels and sailed downriver while the inhabitants of the surrounding countryside pelted them with stones.[4] Soon, the Vikings offered to trade the plunder and prisoners they had taken in exchange for clothes, food, and unhindered downriver journey.[6][4] After that, they rejoined the rest of the fleet on the coast. The weakened fleet, pursued by Abd ar-Rahman's ships, left the Iberian Peninsula after a brief raid in the Algarve.[6]

Aftermath

The city of Seville and its suburbs were left in ruins.[11] The destruction caused by the Viking raiders terrified the people of al-Andalus.[11] Abd ar-Rahman ordered new measures to guard against further raids.[11] He established a naval arsenal (dar al-sina'a) in Seville and built walls around the city and other settlements.[3] Ships and weaponry were made, sailors and troops were raised, and messenger networks were established to spread information about future attacks.[11][7] These measures were successful in frustrating later Viking raids in 859 and 966.[3]

Most of the Vikings sailed back to Francia (modern-day France), and their defeat by the Andalusian army might have discouraged them from attacking the Iberian Peninsula again.[6] It has been alleged by some scholars that shortly after their raid of 844, the Vikings sent an embassy to the court of Abd ar-Rahman, who then sent the poet Yahya ibn al-Hakam (nicknamed Al-Ghazal, "the Gazelle") as an ambassador to the Vikings. However, the key evidence, a thirteenth-century account by Ibn Diḥya, in which an Arab diplomat Al-Ghazāl ("the gazelle") is dispatched to a pagan court during the reign of Abd-ar-Raḥman II, has been shown neither clearly to refer to Vikings nor probably even to have happened.[6][17] According to the Arabist Lévi-Provençal, over time, the few Norse survivors of the raid converted to Islam and settled as farmers in the area of Qawra, Qarmūnâ, and Moron, where they engaged in animal husbandry and made dairy products (reputedly the origin of Sevillian cheese).[18][19] Knutson and Caitlin write that Lévi-Provençal offered no sources for the proposition of conversion to Islam by northern Europeans in al-Andalus and thus it "remains unsubstantiated".[20]

Historiography

Accounts of the Viking raid appeared in the works of Muslim historians, including Ibn al-Qūṭiya of Córdoba (d. 977), Ibn Idhari (wrote c. 1299, copying 10th-century sources), and al-Nuwayri (1284–1332).[9] In the Islamic calendar, the attack took place in the hijri year 230.[21] In the Muslim sources, the Vikings were referred with the epithet the Majus ("fire-worshipper": a term initially used for Zoroastrians in the East).[9][6] Since the Viking fleet attacked the Christian Kingdom of Asturias before raiding Seville, Spanish chronicles also contain records of the Viking raid.[9]

The independent historian Ann Christys opined that many details in the traditional account of the raid might be unreliable. She accepted that the Vikings attacked Lisbon and Seville and threatened Córdoba before being repulsed, but other details such as the names of the commanders of the Muslim defenders were added by later authors, as "it was important for the key players in Christian and Muslim Iberia to claim victory over Vikings".[22]

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ Price 2008, p. 462.

- ^ "ʿAbd al-Wāḥid ben Yazīd al-Iskandarānī, general andalusí". Condadodecastilla.es (in Spanish). 7 April 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kennedy 2014, p. 47.

- ^ a b c Stefánsson 1908, p. 34 quoting ibn al-Qutiyyya

- ^ a b c d e Stefánsson 1908, p. 36 quoting ibn Adhari

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Price 2008, p. 464.

- ^ a b Price 2008, p. 466.

- ^ a b c d e Price 2008, p. 463.

- ^ a b c d Stefánsson 1908, p. 32.

- ^ Stefánsson 1908, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Scheen 1996, p. 69.

- ^ a b c d Stefánsson 1908, p. 36, quoting Nowairi

- ^ a b c d e f Stefánsson 1908, p. 35 quoting ibn Adhari

- ^ Stefánsson 1908, p. 33 quoting ibn al-Qutiyyya

- ^ Scheen 1996, p. 70.

- ^ Stefánsson 1908, p. 37, quoting Nowairi

- ^ Pons-Sanz 2004, p. 6: "There are, however, only three authors who have dealt with al-Ghazᾱl's second embassy in any detail. Each represents one of the prevailing views on the matter... It is my intention in this paper to support the first view, and to present further evidence against the historical reliability of the story."

- ^ James 2009, p. 224.

- ^ Lévi-Provençal 1950, p. 127.

- ^ Knutson & Ellis 2021, p. 551.

- ^ Stefánsson 1908, p. 33.

- ^ Christys 2015, p. 45.

Bibliography

- Christys, Ann (27 August 2015). Vikings in the South: Voyages to Iberia and the Mediterranean. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4742-1378-3.

- James, David, ed. (2009). Early Islamic Spain: The History of Ibn Al-Qūṭīya: A Study of the Unique Arabic Manuscript in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris, with a Translation, Notes, and Comments. Taylor & Francis. p. 127. ISBN 978-0415475525.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2014) [First published 1996]. Muslim Spain and Portugal: A Political History of al-Andalus. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-87041-8.

- Knutson, Sara Ann; Ellis, Caitlin (16 July 2021). "'Conversion' to Islam in Early Medieval Europe: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives on Arab and Northern Eurasian Interactions". Religions. 12 (7): 544. doi:10.3390/rel12070544.

- Lévi-Provençal, Evariste (1950). Histoire de l'Espagne musulmane (in French). G. P. Maisonneuve.

- Price, Neil (31 October 2008). "The Vikings in Spain, North Africa and the Mediterranean". In Stefan Brink; Neil Price (eds.). The Viking World. Routledge. pp. 462–469. ISBN 978-1-134-31826-1.

- Pons-Sanz, Sara M. (2004). "Whom Did Al-Ghazᾱl Meet? An Exchange of Embassies Between the Arabs from Al-Andalus and the Vikings" (PDF). Saga-Book. 28. ISSN 0305-9219.

- Scheen, Rolf (1996). "Vikings raids on the Spanish Peninsula". Militaria. Revista de culturea militar (8). Complutense University of Madrid: 67–88. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- Stefánsson, Jón (1908). "The Vikings in Spain from Arabic (Moorish) and Spanish Sources" (PDF). Saga-Book. 6. London: Viking Society for Northern Research: 32–46.