Women in the Middle Ages

Women in the Middle Ages in Europe occupied a number of different social roles. Women held the positions of wife, mother, peasant, artisan, and nun, as well as some important leadership roles, such as abbess or queen regnant. The very concept of women changed in a number of ways during the Middle Ages,[2] and several forces influenced women's roles during this period, while also expanding upon their traditional roles in society and the economy. Whether or not they were powerful or stayed back to take care of their homes, they still played an important role in society whether they were saints, nobles, peasants, or nuns. Due to context from recent years leading to the reconceptualization of women during this time period, many of their roles were overshadowed by the work of men. Although it is prevalent that women participated in church and helping at home, they did much more to influence the Middle Ages.

Early Middle Ages (476–1000)

In the early Middle Ages, women's lives varied greatly dependent upon their location and status. Ecclesiastical sources offer particularly rich information about women living under Christian rule; some leftovers from the Roman era that offer clues about women elsewhere. For example, following Roman and German Law, women had some limited control over her own marriage, dowry, and property.[3]

As Christianity began to spread, women's roles were largely defined in relation to the Christian Church. For some women, Christianity was attractive due to the independence and autonomy the religion could offer. Christian monasticism allowed women to reject the identity of wife and mother, as well as childbirth, which could be life-threatening. Christian women could have active religious roles: For example, abbesses could become important figures in their own right, occasionally ruling over monasteries of both men and women,[4] and holding significant lands and power. Figures such as Hilda of Whitby (c. 614–680) became influential on a national and even international scale.

For secular Christian women, authority largely was attached to class status. Women such as Radegund were able to contribute to the spread of Christianity through her role as wife and Queen. Wealthy women such as Dhuoda illustrate that female autonomy in the Carolingian era was possible, but women's relationships were largely still shaped around familial and communal connections. In fact, evidence of matronymic names indicate that a matriarchal lineage could be useful when distinguishing a lineage, or when relying on a woman's prominent position within society.[5]

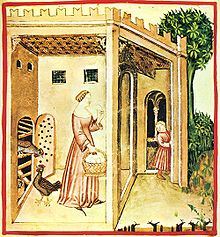

Non-elite women shared labour with their male counterparts, but this work was still largely gendered. Women oversaw household activities such as cooking, brewing, spinning, and weaving, as well as care of livestock. Following Burgundian law and Visigothic law, women might also act as land owners and managers, particularly when they were unmarried, widowed, or when their husbands were away from home.[citation needed]

High Middle Ages (1000–1300)

By the end of the tenth century, Christianity had reached most corners of the European world. Al-Andalus, the region which became modern-day Spain and Portugal, was still largely Islamic, and the Norse countries, while in contact with Christianity, were still undergoing conversion. There is more evidence of Jewish communities being established in towns and cities throughout central Europe. Historians also have more evidence of women (and in general) and how they interacted with the world around them beginning in the High Middle Ages.

Developments within the Christian Church during the eleventh and twelfth centuries impacted women in Western Europe, both religious and secular. The Gregorian Reforms heavily restricted clerical marriage, which in turn affected a number of women who had previously held positions as priest's wives.[6] The Reforms entailed a restructuring of the monastic system which largely excluded women, creating zones that were male only.[7] Moreover, the Reforms triggered a type of repression in which celibacy was a marker of ritual purity distinguishing clerics from laypeople. Women's bodies in turn were viewed as inherently polluting.[8]

At the same time, however, there were aspects of Christianity that enabled female spiritual growth. For a brief moment, double monasteries again became popular, through which abbesses held spiritual and political power (for ex: Fontevraud Abbey). Herrad of Landsberg, Hildegard of Bingen, and Héloïse d'Argenteuil were influential abbesses and authors during this period. Hadewijch of Antwerp was a poet and mystic.

Moreover, the growing cult of Mary Magdalene allowed destitute women, such as the poor, widowed, prostitutes, and former priest's wives to seek refuge at Magdalene houses.[9] The parallel cult of the Virgin Mary reframed contemplation of Christ through Mary's suffering.[10] Regarding the role of women in the Church, Pope Innocent III wrote in 1210: "No matter whether the most blessed Virgin Mary stands higher, and is also more illustrious, than all the apostles together, it was still not to her, but to them, that the Lord entrusted the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven".[11] Both cults allowed secular women to engage with female sanctity where they had been previously excluded due to their non-celibate status.

Secularly, female rulers became incredibly prominent in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. The Empress Matilda fought for the right to rule her father's kingdom, successfully guaranteeing an extension of her lineage and the rule of the Plantagenets. Her son married the infamous, Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122–1204) who was one of the wealthiest and most powerful women in Western Europe during the High Middle Ages. She was the patroness of such literary figures as Wace, Benoît de Sainte-Maure, and Chrétien de Troyes. Eleanor succeeded her father as suo jure Duchess of Aquitaine and Countess of Poitiers at the age of 15. Constance, Queen of Sicily, Urraca of León and Castile, Joan I of Navarre, Melisende, Queen of Jerusalem and other queens regnant exercised political power.

The development of canon law also impacted Christian women's status. The Fourth Lateran Council solidified the need for consent within marriage, assuring women of some autonomy. However, men such as Thomas Aquinas dictated that women owed their husbands a conjugal debt.

Late Middle Ages (1300–1500)

In the Late Middle Ages women such as Saint Catherine of Siena (helped stimulate interest in a crusade with Pope Gregory XI to reform Catholic Church)[12].and Saint Teresa of Ávila (emphasized impact of the love of God on the heart)[13] played significant roles in the development of theological ideas and discussion within the church, and were later declared Doctors of the Roman Catholic Church.[14] The mystic Julian of Norwich was also significant in England for being considered the first woman to write a book that survived and was also written in English.[15]

Isabella I of Castile ruled a combined kingdom with her husband Ferdinand II of Aragon, and Joan of Arc successfully led the French army on several occasions during the Hundred Years' War.

Christine de Pizan was a noted late medieval writer on women's issues. Her Book of the City of Ladies attacked misogyny, while her The Treasure of the City of Ladies articulated an ideal of feminine virtue for women from walks of life ranging from princess to peasant's wife.[16] Her advice to the princess includes a recommendation to use diplomatic skills to prevent war:

If any neighbouring or foreign prince wishes for any reason to make war against her husband, or if her husband wishes to make war on someone else, the good lady will consider this thing carefully, bearing in mind the great evils and infinite cruelties, destruction, massacres and detriment to the country that result from war; the outcome is often terrible. She will ponder long and hard whether she can do something (always preserving the honour of her husband) to prevent this war.[17][page needed]

From the last century of the Middle Ages onwards, restrictions began to be placed on women's work, and guilds became increasingly male-only; some of the reasons may have been the rising status and political role of guilds and the increasing competition from cottage industries, which prompted the guilds to tighten their entrance requirements.[18] Female property rights also began to be curtailed during this period.[19][why?]

Marriage

Medieval marriage was both a private and social matter. According to canon law, the law of the Catholic Church, marriage was a concrete exclusive bond between husband and wife; giving the husband all power and control in the relationship.[20] Husband and wife were partners and were supposed to reflect Adam and Eve. Even though wives had to submit to their husbands' authority, wives still had rights in their marriages. McDougall concurs with Charles Reid's argument that both men and women shared rights in regards to sex and marriage; which includes: "the right to consent to marriage, the right to ask for marital debt or conjugal (sexual) duty, the right to leave a marriage when they either suspected it was invalid or had grounds to sue for separation, and finally the right to choose one's own place of burial, death being the point at which a spouse's ownership of the other spouse's body ceased".[21]

Regionally and across the time span of the Middle Ages, marriage could be formed differently. Marriage could be proclaimed in secret by the mutually consenting couple, or arranged between families as long as the man and woman were not forced and consented freely; but by the 12th century in western canon law, consent (whether in mutual secrecy or in a public sphere) between the couple was imperative.[22] Marriages confirmed in secrecy were seen as problematic in the legal sphere due to spouses redacting and denying that the marriage was solidified and consummated.[23]

Peasants, slaves, and maidservants and generally lower class women needed the permission and consent of their master in order to marry someone; and if they did not they were punished (see below in Law).

Marriage also allowed for the couples' social networks to expand. This was according to Bennett (1984) who investigated the marriage of Henry Kroyl Jr. and Agnes Penifader, and how their social spheres changed after their marriage. Due to the couples' fathers, Henry Kroyl Sr. and Robert Penifader being prominent villagers in Brigstock, Northamptonshire, approximately 2,000 references to the activities of the couple and their immediate families were being recorded. Bennett details how Kroyl Jr.'s social network expanded greatly as he gained connections through his occupational endeavors.

Agnes' connections expanded also based on Kroyl Jr.'s new connections. However, Bennett also signifies that a familial alliance between the couples' families of origin did not form. Kroyl Jr. had limited contact with his father after his marriage, and his social network expanded from the business he conducted with his brothers and other villagers. Agnes, though all contact with her family did not cease, her social network expanded to her husband's family of origin and his new connections.

Widowhood and remarriage

Upon the death of a spouse, widows could gain power in inheriting their husbands' property as opposed to adult sons. Male-preference primogeniture stipulated that the male heir was to inherit their deceased father's land; and in cases of no sons, the eldest daughter would inherit property. However, widows could inherit property when they had minor sons, or if provisions were made for them to inherit.[24] Peter Franklin (1986) investigated the women tenants of Thornbury during the Black Death due to the higher than average proportion of women tenants. Through court rolls, he found that many widows in this area independently held land successfully. He argued that some widows may have remarried due to keeping up with their tenure and financial difficulties of holding their inherited land, or community pressures for the said widow to remarry if she had a male servant living in her home. Remarriage would put the widow back under the thumb and control of her new husband.[25] However, some widows never remarried and held the land until their deaths, thereby ensuring their independence. Even young widows, who would have had an easier time remarrying, remained independent and unmarried. Franklin considers the lives of widows to have been "liberating" because women had more autonomous control over their lives and property; they were able to "argue their own cases in court, hire labour, and cultivate and manage holdings successfully".[25]

Franklin also discusses that some Thornbury widows had second and even third marriages. Remarriage would have affected inheritance of property, especially if the widow had children with her second husband; however there are several cases where sons from the widow's first marriage were able to inherit before the second husband.[26]

McDougall also notes like the varying forms of marriage, the canon law regarding remarriage varied across regions. Both men and women could have been permitted to freely remarry or may have been restricted and/or deemed to serve penance before remarrying.[27]

Medieval elite women

In the Middle Ages the upper socioeconomic groups generally included royalty and nobility. Conduct books from the period present an image of the role of elite women being to obey their spouse, guard their virtue, produce offspring, and to oversee the operation of the household. For those women who did adhere to these traditional roles, the responsibilities could be considerable, with households sometimes including dozens of people. Further, when their husbands were away the role of women could increase substantially. By the High and Late Middle Ages there were numerous royal and noble women who assumed control of their husbands' domains in their absence, including defense and even bearing arms.[28]

Noble women were natural parts of the cultural and political environments of their time due to their positions and kinship. Particularly when acting as regents, elite women would assume the full feudal, economic, political and judicial powers of their husbands or young heirs. These women were never prohibited during the Middle Ages from receiving fiefdoms or owning real property during their husbands' lives. Noble women were often patrons of literature, art, monasteries and convents, and religious men. It was not uncommon for them to be knowledgeable in Latin literature.[29]

Medieval peasant women

As with peasant men, the life of peasant women was difficult. In terms of labour, women of the peasantry had more gender equality than in the nobility. However, most scholars agree that impoverished women had fundamentally the same subordinate status as women elsewhere in medieval society.[30] Women were generally prohibited from acting as elected town officials, and likely only attended village meetings if they were unmarried, or widowed.[31] Due to poor nutrition and the dangers of childbirth, women's life expectancy at birth was less than that of male peasants: perhaps 25 years.[32] As a result, in some places there were four men for every three women.[32]

Chris Middleton made these general observations about English peasant women: "A peasant woman's life was, in fact, hemmed in by prohibition and restraint."[33] If single, women had to submit to the male head of her household; if married, to her husband, under whose identity she was subsumed. English peasant women generally could not hold lands for long, rarely learnt any craft occupation and rarely advanced past the position of assistants, and could not become officials.

Peasant women had numerous restrictions placed on their behaviour by their lords. If a woman was pregnant, and not married, or had sex outside of marriage, the lord was entitled to compensation. The control of peasant women was a function of financial benefits to the lords. They were not motivated by women's moral state. Also during this period, sexual activity was not regulated, with couples simply living together outside a formal ceremony, provided they had permission by their lord. Even without a feudal lord involved with her life, a woman still had supervision by their father, brothers or other male members of the family. Women had little control over their own lives.[34]

Middleton provided some exceptions: English peasant women, on their own behalf, could plead in manorial courts; some female freeholders enjoyed immunities from male peers and landlords; and some trades (such as ale-brewing), provided female workers with independence. Still, Middleton viewed these as exceptions which required historians only to modify, rather than revise, "the essential model of female subservience."[33]

Overview of the medieval European economy

In medieval Western Europe, society and economy were rural-based. Ninety percent of the European population lived in the countryside or in small towns.[35] Agriculture played an important role in sustaining this rural-based economy.[36] Due to the lack of mechanical devices, activities were performed mostly by human labour.[35] Both men and women participated in the medieval workforce and most workers were not paid by wages for their labour, but instead independently worked on their land and produced their own goods for consumption.[36] Whittle cautioned against the "modern assumption that active economic involvement and hard work translate into status and wealth" because during Middle Ages, hard work only ensured survival against starvation. In fact, although peasant women worked as hard as peasant men, they suffered many disadvantages such as fewer landholdings, occupational exclusions, and lower wages.[37]

Labour

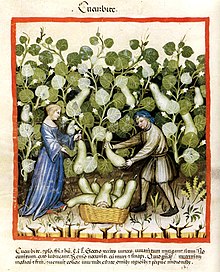

Generally, research has determined that there is limited gender division of labour among peasant men and women. Rural historian Jane Whittle described this gender division of labour thus: "Labour was divided according to the workers' gender. Some activities were restricted to either men or women; other activities were preferred to be performed by one gender over the other:" e.g. men ploughed, mowed, and threshed and women gleaned, cleared weeds, bound sheaves, made hay, and collected wood; and yet others were performed by both, such as harvesting.[35]

A woman's standing as a worker might vary depending on circumstances. Generally, women were required to have male guardians who would assume legal liability for them in legal and economic matters: For the wives of elite merchants in Northern Europe[vague], their roles extended to commercial undertakings both with their husbands and on their own, however in Italy tradition and law excluded them from commerce;[28] in Ghent, women had to have guardians unless these women had been emancipated or were prestigious merchants; Norman women were forbidden to contract business ventures; French women could litigate business matters, but could not plead in courts without their husbands, unless they had suffered from their husbands' abuses;[38] Castilian wives, during the Reconquista, enjoyed favourable legal treatments, worked in family-oriented trades and crafts, sold goods, kept inns and shops, became domestic servants for wealthier households; Christian Castilian wives laboured along with Jewish and Muslim free-born women and slaves. Yet over time Castilian wives' work became associated with or even subordinated to that of their husbands, and when the Castilian frontier region had been stabilized, Castilian wives' legal standing deteriorated.[39]

Both peasant men and women worked in the home and out in the fields. In looking at coroner records for 14th-century rural England detailing the accidental deaths of 1,000 people, which represent the lives of peasants more clearly, Barbara Hanawalt found that 30% of women died in their homes compared to 12% of men; 9% of women died on a private property (i.e. a neighbour's house, a garden area, manor house, etc.) compared to 6% of men; 22% of women died in public areas within their village (i.e. greens, streets, churches, markets, highways, etc.) compared to 18% of men.[40] Men dominated accidental deaths within fields at 38% compared to 18% of women, and men had 4% more accidental deaths in water than women did. Accidental deaths of women (61%) occurred within their homes and villages; while men had only 36%.[40] This information correlated with the activities and labours regarding the maintenance and responsibilities of working in a household. These include: food preparation, laundry, sewing, brewing, getting water, starting fires, tending to children, collecting produce, and working with domestic animals. Outside of the household and village, 4% of women died in agricultural accidents compared to 19% of men, and no women died from labours of construction or carpentry.[40] The division of gendered labour may be due to women's being at risk of danger, like being attacked, raped and losing their virginity, in doing work in the fields or outside of the home and village.[40]

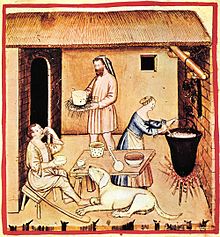

Three main activities performed by peasant men and women were planting foods, keeping livestock, and making textiles, as depicted in Psalters from southern Germany and England. Women of different classes performed different activities: rich urban women could be merchants like their husbands or even became money lenders; middle-class women worked in the textile, inn-keeping, shop-keeping, and brewing industries; while poorer women often peddled and huckstered foods and other merchandise in the market places, or worked in richer households as domestic servants, day labourers, or laundresses.[41] Modern historians assumed that only women were assigned childcare and thus had to work near their home, yet childcare responsibilities could be fulfilled far from the home and—except breastfeeding—were not exclusive to women.[42] In spite of the patriarchal medieval European culture,[43] which posited female inferiority, opposed female independence,[36] so that female workers could not contract out their labour services without their husband's' approval,[44] widows have been recorded to act as independent economic agents; meanwhile, a married woman—mostly from among the female artisans—could, under some limited circumstances, exercise some agency as a femme sole, identified legally and economically as separate from her husband: she could learn artisan skills from her parents as their apprentice, she could work alone, conduct business, contract her labours, or even plead in law-courts.[45]

There was evidence that women performed not only housekeeping responsibilities like cooking and cleaning, but even other household activities like grinding, brewing, butchering, and spinning; and produced items like flour, ale, meat, cheese, and textile for direct consumption and for sale.[37] An anonymous 15th-century English ballad appreciated activities performed by English peasant women such as housekeeping, making foodstuffs and textiles, and childcare.[37] Even though cloth-making, brewing, and dairy production were trades associated with female workers, male cloth-makers and brewers increasingly displaced female workers, especially after water-mills, horizontal looms, and hop-flavoured beers were invented. These inventions favoured commercial cloth-making and brewing dominated by male workers who had more time, wealth, and access to credit and political influence and who produced goods for sale instead of for direct consumption. Meanwhile, women were increasingly relegated to low-paying tasks like spinning.[46]

Besides working independently on their own lands, women could hire themselves out as servants or wage-workers. Medieval servants performed works as required by the employer's household: men cooked and cleaned while women did the laundry. Like their independent rural workers, rural wage-labourers performed complementary tasks based on a gendered division of labour. Women were paid only half as much as men even though both sexes performed similar tasks.[47]

After the Black Death killed a large part of the European population and led to severe labour shortages, women filled out the occupational gaps in the cloth-making and agricultural sectors.[48] Simon Penn argued that the labour shortages after the Black Death furnished economic opportunities for women, but Sarah Bardsley and Judith Bennett countered that women were paid about 50–75% of men's wages. Bennett attributed this gender-based wage-gap to patriarchal prejudices which devalued women's work, yet John Hatcher disputed Bennet's claim: he pointed out that men and women received the same wages for the same piece-work, but women received lower day-wages because they were physically weaker and might have had to sacrifice working hours for other domestic duties. Whittle stated that the debate has not yet been settled.[49]

To illustrate, the late medieval poem Piers Plowman paints a pitiful picture of the life of the medieval peasant woman:

Burdened with children and landlords' rent;

What they can put aside from what they make spinning they spend on housing,

Also on milk and meal to make porridge with

To sate their children who cry out for food

And they themselves also suffer much hunger,

And woe in wintertime, and waking up nights

To rise on the bedside to rock the cradle,

Also to card and comb wool, to patch and to wash,

To rub flax and reel yarn and to peel rushes

That it is pity to describe or show in rhyme

The woe of these women who live in huts;[50]

Peasant women by status

The first group of peasant women consisted of free landholders. Early records such as the Exon Domesday and Little Domesday attested that, among English land-owners, 10–14% noble thegns and non-noble free-tenants were women; and Wendy Davies found records which showed that in 54% of property transactions, women could act independently or jointly with their husbands and sons.[51] Still, only after the 13th century are there records which better showed free female peasants' rights to land.[51] In addition, English manorial court-rolls recorded many activities carried out by free peasants such as selling and inheriting lands, paying rents, settling upon debts and credits, brewing and selling ale, and—if unfree—rendering labour services to lords. Free peasant women, unlike their male counterparts, could not become officers such as manorial jurors, constables, and reeves.[44]

The second category of medieval European workers were serfs. Conditions of serfdom applied to both genders.[44] Serfs did not enjoy property rights as did free tenants: serfs were restricted from leaving their lords' lands at will and were forbidden to dispose of their assigned holdings.[52] Both male and female serfs had to labour as part of their services to their lords and their required activities might be even specifically gendered by the lords. Many serfs also had no choice but to be controlled by their Lords, as in turn from protection from tax collectors and other protections, they were bound to them, which is an early example of taking advantage of peasants/serfs who had their roles more concrete in society.[53] A serf woman would pass her serfdom status to her children; in contrast, children would inherit gentry status from their father.[54] A serf could gain freedom when released by the lord, or after having escaped from the lord's control for one year plus one day, often into towns; escaping serfs were rarely arrested.[55]

When female serfs got married, they had to pay fines to their lords. The first fine upon a female serf getting married was known as merchet, to be paid by her father to their lord; the rationale was that the lord had lost a worker and her children.[56][57] The second fine is the leyrwite, to be paid by a male or female serf who had committed sexual acts forbidden by the Church, for fear that the fornicating serf might have her marriage value lessened and thus the lord might not get the merchet.[58]

Chris Middleton cited other historians who demonstrated that lords often regulated their serfs' marriages to make sure that the serfs' landholdings would not be taken out of their jurisdiction. Lords could even force female serfs into involuntary marriages to ensure that the female serfs would be able to pro-create a new generation of workers. Over time, English lords increasingly favoured primogeniture inheritance patterns to prevent their serfs' landholdings from being broken up.[59]

Health

Peasant women during the time period were subjected to a number of superstitious practices when it came to their health. In The Distaff Gospels, a collection of 15th-century French women's lore, advice for women's health was plentiful. "For a fever, write the first 3 words of the Our Father on a sage leaf, eat it in the morning for 3 days and you will be cured."[60]

Male involvement with women's healthcare was widespread. However, there were limits to male participation because of the resistance to males' viewing women's genitalia.[61] During most encounters with male medical practitioners, women remained clothed because viewing a women's body was considered shameful.

Childbirth was treated as the most important aspect of women's health during the period; however, few historical texts document the experience. Women attendants assisted in childbirth and passed their experiences to one another. In addition to serving as midwives or nuns, women also served in other scattered capacities ranging from physicians to empirical healers, even when they unequaled compared to roles men held, they still found a way to serve in important capacities.[62] Midwives, women who attended childbirth, were acknowledged as legitimate medical specialists and were granted a special role in women's health care.[63] There is Roman documentation in Latin works evidencing the professional role of midwives and their involvement with gynaecological care.[63] Women were healers and engaged in medical practices. In 12th-century Salerno, Italy, Trota, a woman, wrote one of the Trotula texts on diseases of women.[64] Her text, Treatments for Women, addressed events in childbirth that called for medical attention. The book was a compilation of three original texts and quickly became the basis for the treatment of women. Based on medical information developed in Greek and Roman eras, these texts discussed ailments, disease, and possible treatments for women's health issues.

The Abbess Hildegard of Bingen, classed among medieval single women, wrote, in her 12th-century treatise Physica and Causae et Curae, about many issues concerning women's health. Hildegard was one of the most well known of medieval medical authors. In particular, Hildegard contributed much valuable knowledge in the use of herbs as well as observations regarding women's physiology and spirituality. In nine sections, Hildegard's volume reviews the medical uses for plants, the earth's elements (earth, water, and air), and animals. Also included are investigations of metals and jewels. Hildegard also explored such issues as laughter, tears, and sneezing, on the one hand, and poisons and aphrodisiacs, on the other. Her work was compiled in a religious environment but also relied on past wisdom and new findings about women's health. Hildegard's work not only addresses illness and cures but also explores the theory of medicine and the nature of women's bodies.[64]

Diet

Just as Classical Greco-Roman writers, including Aristotle, Pliny the Elder, and Galen, assumed that men lived longer than women,[65] medieval Catholic bishop Albertus Magnus agreed that in general men lived longer, but he observed that some women live longer and posited that it was per accidens, thanks to the purification resulting from menstruation and that women worked less but also consumed less than men.[66] Modern historians Bullough and Campbell instead attribute high female mortality during the Middle Ages to deficiency in iron and protein as a result of the diet during the Roman period and the early Middle Ages. Medieval peasants subsisted upon grain-heavy, protein-poor and iron-poor diets, eating breads of wheat, barley, and rye dipped in broth, and rarely enjoying nutritious supplements like cheese, eggs, and wine.[67] Physiologically speaking, women require at least twice as much iron as men because women inevitably lose iron through menstrual discharge as well as to events related to child bearing, including fetal needs; bleeding during childbirth, miscarriage, and abortion; and lactation. As the human body better absorbs iron from liver, iron salts, and meat than from grains and vegetables, the grain-heavy medieval diet commonly resulted in iron deficiency and, by extension, general anemia for medieval women. However, anemia was not the leading cause of death for women; rather anemia, which lessens the amount of hemoglobin in blood, would further aggravate such other diseases as pneumonia, bronchitis, emphysema, and heart diseases.[68]

Since the 800s, the invention of a more efficient type of plough—along with three-field replacing two-field crop rotation—allowed medieval peasants to improve their diets through planting, alongside wheat and rye in the fall, oats, barley, and legumes in the spring, including various protein-rich peas.[67] In the same period, rabbits were introduced from the Iberian Peninsula across the Alps to the Carolingian Empire, reaching England in the 12th century. Herring could be more effectively salted, and pork, cheese, and eggs were increasingly consumed throughout Europe, even by the lower classes.[67] As a result, Europeans of all classes consumed more proteins from meats than did people in any other part of the world during the same period—leading to population growth that almost outstripped resources at the onset of the devastating Black Death.[69] Bullough and Campbell further cite David Herlihy, who observes, based on available data, that in European cities in the 15th century, women outnumbered men, and although they did not have the "absolute numerical advantage over men," women were more numerous among the elderly.[66] A noteworthy difference with in the population of men and women is that women under the age of fifteen outnumbered men 105 to 99. However, over the age of fifteen and still unmarried men outnumbered women. Many women were married at a younger age, which contributed to those numbers. This is important while considering medical treatment of the time which often proved to be misogynistic in nature.[70]

Landownership

To prosper, medieval Europeans needed rights to own land, dwellings, and goods.[36]

Land-ownership involved various inheritance patterns, according to the potential heir's gender across the landscape of medieval Western Europe. Primogeniture prevailed in England, Normandy, and the Basque region: In the Basque region, the eldest child—regardless of sex—inherited all lands[citation needed]. In Normandy, only sons could inherit lands. In England, the eldest son usually inherited all properties, but sometimes sons inherited jointly, daughters would inherit only if there were no sons. In Scandinavia, sons received twice as much as daughters' inheritance, yet siblings of the same sex received equal shares. In northern France, Brittany, and the Holy Roman Empire, sons and daughters enjoyed partible inheritance: each child would receive an equal share regardless of sex (but Parisian parents could favour some children over others).[71]

Female land-owners, single or married, could grant or sell land as they deemed fit.[51] Women managed the estates when their husbands left for war, political affairs, and pilgrimages.[51] Nevertheless, as time passed, women were increasingly given, as dowries, movable properties such as good and cash instead of land. Even though up the year 1000 female landownership had been increasing, afterwards female landownership began to decline.[42] Commercialization also contributed to the decline in female landownership as more women left the countryside to work for wages as servants or day labourers.[35] Medieval widows independently managed and cultivated their deceased husbands' lands.[42] Overall, widows were preferred over children to inherit lands: indeed, English widows would receive one third of the couples' shared properties, but in Normandy widows could not inherit.[72]

Notable examples of women landowners in England in the Middle Ages include: countess Gytha, mother of Harold Godwinson, who held lands across the south west of England; Asa, who held land in Yorkshire; and Judith, who owned large amounts of land in the East Midlands (all three women and their claims are recorded in the Domesday Book);[73] and Margaret de Neville, who owned extensive lands in 13th-14th century Yorkshire.[74]

Law

Cultural differences across Western and Eastern Europe meant that laws were neither universal nor universally practised. The Laws of the Salian Franks, a Germanic tribe that migrated into Gaul and converted to Christianity between the 6th and 7th centuries, provide a well-known example of a particular tribe's law codes. According to Salic Law, crimes and determined punishments were usually orated; however as their contact with literate Romans increased, their laws became codified and developed into written language and text. Other examples of women appearing in legal records come from court leet jurisdiction and borough ordinances in England where they are frequently cited for crimes involving labor, theft, and even occasionally for murder.

Peasants, slaves, and maidservants were considered as property of their free-born master(s). In some or perhaps most cases, the unfree person might be regarded as of the same value as their master's animals. However, peasants, slaves, and maidservants of the king were regarded as more valuable and even considered to be of the same value as free persons because they were members of the king's court.

- Crimes concerning abduction

If someone were to abduct another person's slave or maidservant and were proven to have committed the crime, that individual would be responsible to pay 35 solidi, the value of the slave, and in addition a fine for lost time of use. If someone abducted another person's maidservant, the abductor would be fined 30 solidi. A proven seducer of a maidservant worth 15 or 25 solidi, and who is himself worth 25 solidi, would be fined 72 solidi plus the value of the maidservant. The proven abductor of a boy or girl domestic servant will be fined the value of the servant (25 or 35 solidi) plus an additional amount for lost time of use.[75]

- Crimes concerning free-born persons marrying slaves

A free-born woman who marries a slave will lose her freedom and privileges as a free-born woman. She will also have her property taken away from her and will be proclaimed an outlaw. A free-born man who marries a slave or maidservant shall also lose his freedom and privilege as a free-born man.[76]

- Crimes concerning fornication with slaves or maidservants

If a freeman fornicates with another person's maidservant and is proven to have done so, he will be required to pay the maidservant's master 15 solidi. If anyone fornicates with a maidservant of the king and proven to do so, the fine would be 30 solidi. If a slave fornicates with another person's maidservant and that maidservant dies, the slave will be fined and also be required to pay the maidservant's master 6 solidi and may be castrated; or that slave's master will be required to pay the maidservant's master the value of the deceased maidservant. If a slave fornicates with a maidservant who does not die, the slave will either receive three hundred lashes or be required to pay the maidservant's master 3 solidi. If a slave marries another person's maidservant without her master's consent, the slave will either be whipped or required to pay the maidservant's master 3 solidi.[76]

Crimes concerning labor

There is evidence in the Leet Jurisdiction in the City of Norwich from the 13th and 14th centuries that women were charged with breaking the assize of ale as well as keeping back money from the sale of corn.[77] Women were also cited with buying corn outside of the city walls where taxes were not collected and either keeping it for their families or re-selling it and making an illegal profit.[77] Women listed as bakers, poulterers, brewers, and books were also cited as transgressors of borough ordinances in York in 1301.[78] One study found that women were more involved in crimes against the market in one particular town in England after the Black Plague than they were before.[79]

Civil discourse of women

Although many women served in more traditional roles, and it was mainly men who had a more influential hold over society, that does not mean women did not participate in civil discourse. Even though the voices of women were heavily suppressed due to society's undemocratic nature, they still had a voice through writing, or in courts or synod. Although there are not many interpretations available on women's civic practices, it is believed that they participated heavily through writings and letters, a quieter way of participation.[80]

Involvement in the Church

Women had much involvement in the church as religion is very important to the Middle Ages. However, one of the most prominent roles a woman could be in the church was serving as a nun or working in a hospital (mostly nuns as well). Women generally participated in the church in a different way than men would, as well as having different beliefs, such as purifying women after birth, or denying communion to menstruating women. Many ideas were conceptualized by men about women in the church which led to such treatment because of gender roles.[81]

Difference between Western and Eastern Europe

The status of women differed immensely by region. In most of Western Europe, later marriage and higher rates of definitive celibacy (the so-called "European marriage pattern") helped to constrain patriarchy at its most extreme level. The rise of Christianity and manorialism had both created incentives to keep families nuclear and thus the age of marriage increased; the Western Church instituted marriage laws and practices that undermined large kinship groups. From as early as the 4th century, the Church discouraged any practice that enlarged the family, like adoption, polygamy, taking concubines, divorce, and remarriage. The Church severely discouraged and prohibited consanguineous marriages, a marriage pattern that has constituted a means to maintain clans (and thus their power) throughout history.[82] The church also forbade marriages in which the bride did not clearly agree to the union.[83] After the Fall of Rome, manorialism also helped to weaken the ties of kinship and thus the power of clans; as early as the 9th century in Austrasia, families that worked on manors were small, consisting of parents and children and occasionally a grandparent. The Church and state had become allies in erasing the solidarity and thus the political power of the clans; the Church sought to replace traditional religion, whose vehicle was the kin group, and substituting the authority of the elders of the kin group with that of a religious elder; at the same time, the king's rule was undermined by revolts on the part of the most powerful kin groups, clans or sections, whose conspiracies and murders threatened the power of the state and also the demand of manorial lords for obedient, compliant workers.[84] As the peasants and serfs lived and worked on farms that they rented from the lord of the manor, they also needed the permission of the lord to marry; couples therefore had to comply with the lord and wait until a small farm became available before they could marry and thus produce children. Those who could and did delay marriage presumably were rewarded by the landlord and those who did not were presumably denied said reward.[85] For example, Medieval England saw the marriage age as variable depending on economic circumstances, with couples delaying marriage until the early twenties when times were bad and frequently marrying in the late teens after the Black Death, when there were labour shortages and it was economically lucrative to workers;[86] by appearances, marriage of adolescents was not the norm in England.[87]

In Eastern Europe however, there were many differences with specific regional characteristics. In the Byzantine Empire and Bulgarian Empire, the majority of women were well educated and had a higher social status than in Western Europe.[88] Equality in family relations and the right to common property after marriage were recognized by law with the Ekloga, issued in Constantinople in 726 and Slavonic Ekloga in Bulgaria in the 9th century.[89] In some parts of Russia the tradition of early and universal marriage (usually of a bride age 12–15, with menarche occurring on average at 14)[90] as well as traditional Slavic patrilocal customs[91] led to a greatly inferior status for women at all levels of society.[92] In rural South Slavic areas, a custom of women marrying men younger than themselves, in some cases only after the age of thirty, remained until the 19th century.[93] The manorial system had yet to penetrate into Eastern Europe where there was a lesser effect on clan systems and no firm enforcement of bans on cross-cousin marriages.[94] Orthodox laws banned marriages between relatives closer than third and fourth cousins. [95]

See also

- Ancillae

- Female education (Medieval)

- Medieval literature (Women's)

- Medieval female sexuality

- Prostitution (Middle Ages)

- Women artists (Medieval)

- Women in Judaism (Middle Ages)

- Women in science (Medieval)

- Timeline of women in medieval warfare

- Clothing:

References

- ^ Backhouse, Janet (2000). Medieval Rural Life in the Luttrell Psalter. British Library. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 0-8020-8399-4. OCLC 44069050.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Allen 2006a, p. 6.

- ^ Stuard, Susan (1976). Women in Medieval Society. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 13–14.

- ^ Cramer, Thomas (2011). "Defending the Double Monastery: Gender and Society in Early Medieval Europe". ProQuest.

- ^ Stuard, Susan (1976). Women in Medieval Society. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 18–21.

- ^ Griffiths, Fiona (2013). "Women and Reform in the Central Middle Ages". The Oxford Handbook of Women and Gender in Medieval Europe.

- ^ McNamara, Jo Ann (1994). "The Herrenfrage: The Restructuring of the Gender System, 1050–1150". Medieval Masculinities: Regarding Men in the Middle Ages: 5.

- ^ Elliott, Dyan (1998). Fallen Bodies: Pollution, Sexuality, and Demonology in the Middle Ages.

- ^ Nowacka, Keiko (2007). Pastoral Care of Prostitutes in Paris, c. 1180-1250.

- ^ Rubin, Mary (2009). Mother of God: A History of the Virgin Mary.

- ^ Innocent III, Epistle, 11 December 1210

- ^ Scott, Karen (1992). "St. Catherine of Siena, "Apostola"". Church History. 61 (1): 34–46. doi:10.2307/3168001. ISSN 0009-6407. JSTOR 3168001.

- ^ Knuth, Elizabeth (1994). "The Gift of Tears in Teresa of Avila". Mystics Quarterly. 20 (4): 131–142. ISSN 0742-5503. JSTOR 20717226.

- ^ "Saint Catherine of Siena | Biography, Facts, Miracles, & Patron Saint Of | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ^ McAvoy, Liz Herbert (2002). "Julian of Norwich and a Trinity of the Feminine". Mystics Quarterly. 28 (2): 68–77. ISSN 0742-5503. JSTOR 20717491.

- ^ Allen 2006b, p. 646.

- ^ de Pizan 2003.

- ^ Schaus 2006, p. 337.

- ^ Erler & Kowaleski 2003, p. 198.

- ^ McDougall 2013, p. 164

- ^ McDougall 2013, p. 165

- ^ McDougall 2013, p. 166

- ^ McDougall 2013, p. 167

- ^ Franklin 1986, p. 189

- ^ a b Franklin 1986, p. 196

- ^ Franklin 1986, pp. 198, 201

- ^ McDougall 2013, pp. 168–169

- ^ a b Schaus 2006, p. 767.

- ^ Schaus 2006, pp. 609, 610.

- ^ Bennett, Judith M. 1987. Women in the Medieval English Countryside: Gender and Household in Brigstock Before the Plague. P. 5-6. 'The findings described in the following chapters suggest that a bon vieux temps will not be found in the medieval countryside ... The evidence that follows indicates that rural women faced limitations fundamentally similar to those restricting women of the more privileged sectors of medieval society. Norms of female and male behaviour in the medieval countryside drew heavily upon the private subordination of wives to their husbands.'

- ^ Shahar, Shulamith (1983). The Fourth Estate: A History of Women in the Middle Ages. Routledge. pp. 220–21.

- ^ a b Williams & Echols 1994, p. 241.

- ^ a b Middleton 1981, p. 107.

- ^ Middleton 1981, p. 144

- ^ a b c d Whittle 2010, p. 312.

- ^ a b c d Whittle 2010, p. 313.

- ^ a b c Whittle 2010, p. 311.

- ^ Reyerson 2010, p. 299.

- ^ Reyerson 2010, p. 297.

- ^ a b c d Hanawalt 1998, p. 20

- ^ Reyerson 2010, p. 295-296.

- ^ a b c Whittle 2010, p. 316.

- ^ Whittle 2010, pp. 315–316.

- ^ a b c Whittle 2010, p. 315.

- ^ Reyerson 2010, p. 295-296, 298, 300.

- ^ Whittle 2010, pp. 317–320.

- ^ Whittle 2010, pp. 320, 322.

- ^ Whittle 2010, pp. 313, 320.

- ^ Whittle 2010, p. 322.

- ^ William Langland, tr. George Economou, William Langland's Piers Plowman: the C version : a verse translation, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996, ISBN 0-8122-1561-3, p. 82.

- ^ a b c d Whittle 2010, p. 314.

- ^ Middleton 1981, p. 139.

- ^ "Serfdom | History & Examples | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Harding 1980, p. 423.

- ^ Dowty 1989, p. 25.

- ^ Vinogradoff 1892.

- ^ Middleton 1981, pp. 138, 143.

- ^ Middleton 1981, p. 144.

- ^ Middleton 1981, p. 137.

- ^ Garay & Jeay 2007, p. 424

- ^ Green 2013, p. 346

- ^ Green, Monica (1989). "Women's Medical Practice and Health Care in Medieval Europe". Signs. 14 (2): 434–473. ISSN 0097-9740. JSTOR 3174557.

- ^ a b Green 2013, p. 347

- ^ a b Garay & Jeay 2007

- ^ Bullough & Campbell 1980, p. 317

- ^ a b Bullough & Campbell 1980, p. 318

- ^ a b c Bullough & Campbell 1980, p. 319

- ^ Bullough & Campbell 1980, p. 322

- ^ Bullough & Campbell 1980, p. 320

- ^ Bullough & Campbell 1980.

- ^ Whittle 2010, p. 314-315.

- ^ Whittle 2010, p. 314-5.

- ^ Stafford, Pauline. "Women in Domesday". In Bates, K (ed.). Medieval Women in Southern England. pp. 75–77.

- ^ McNiven, Peter (2004). "Neville [de Neville] family (per. c. 1267–1426), gentry". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/54532. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 29 October 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Rivers 1986.

- ^ a b Schaus 2006, p. 44.

- ^ a b Norwich (England); Hudson, William (1892). Leet jurisdiction in the city of Norwich during the XIIIth and XIVth centuries: with a short notice of its later history and decline, from rolls in the possession of the Corporation. The Publications of the Selden Society ;v. 5. London: B. Quaritch. p. 12.

- ^ Goldberg, P. J. P. (1 January 2013). Women in England c. 1275–1525. Manchester University Press. pp. 185–187. doi:10.7765/9781526112613. ISBN 978-1-5261-1261-3.

- ^ McGibbon Smith, Erin (2005), "Court Rolls as Evidence for Village Society: Sutton-in-the-Isle in the Fourteenth Century", Town and Countryside in the Age of the Black Death, The Medieval Countryside, vol. 1, Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, pp. 245–276, doi:10.1484/m.tmc-eb.1.100563, ISBN 978-2-503-53517-3, retrieved 11 March 2023

- ^ Ramsey, Shawn D. (2012). "The Voices of Counsel: Women and Civic Rhetoric in the Middle Ages". Rhetoric Society Quarterly. 42 (5): 472–489. ISSN 0277-3945. JSTOR 41722453.

- ^ Sweetinburgh, Sheila (2019), Blud, Victoria; Heath, Diane; Klafter, Einat (eds.), "Religious women in the landscape: their roles in medieval Canterbury and its hinterland", Gender in medieval places, spaces and thresholds, University of London Press, pp. 9–24, doi:10.2307/j.ctv9b2tw8.8, ISBN 978-1-909646-84-1, JSTOR j.ctv9b2tw8.8, retrieved 19 December 2022

- ^ Bouchard 1981, pp. 269–270.

- ^ Greif 2006, p. 309.

- ^ Heather 1999, pp. 142–148.

- ^ 2014. Medieval Manorialism and the Hajnal Line

- ^ Hanawalt 1986, p. 96.

- ^ Hanawalt 1986, pp. 98–100.

- ^ Georgieva 2003.

- ^ Dimitrov, D. 2011. Byzantine Empire and Byzantine world, Prosveta - Sofia, p. 83

- ^ Levin 1995, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Levin 1995, pp. 137, 142.

- ^ Levin 1995, pp. 225–227.

- ^ Mackenzie, G. Muir (1877). Travels in The Slavonic Provinces of Turkey-in-Europe. London : Daldy, Isbister and Co. p. 128.

- ^ Mitterauer 2010, pp. 45–48, 77.

- ^ Levin 1995, pp. 137–139.

Sources

- Allen, Prudence (2006a). The Early Humanist Reformation, 1250-1500, Part 1. The Concept of Woman. Vol. 2. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802833464.

- Allen, Prudence (2006b). The Early Humanist Reformation, 1250-1500, Part 2. The Concept of Woman. Vol. 2. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802833471.

- Bennett, Judith M. (1984). "The Tie That Binds: Peasant Marriages and Families in Late Medieval England". The Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 15 (1): 111–129. doi:10.2307/203596. JSTOR 203596.

- Bouchard, Constance B. (1981). "Consanguinity and Noble Marriages in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries". Speculum. 56 (2): 268–287. doi:10.2307/2846935. JSTOR 2846935. PMID 11610836. S2CID 38717048.

- Bullough, Vern; Campbell, Cameron (1980). "Female Longevity and Diet in the Middle Ages". Speculum. 55 (2): 317–325. doi:10.2307/2847291. JSTOR 2847291. PMID 11610728. S2CID 27230917.

- Classen, Albrecht (2007). Old age in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance: interdisciplinary approaches to a neglected topic. Fundamentals of Medieval and Early Modern Culture. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3110195484.

- Dowty, Alan (1989). Closed Borders: The Contemporary Assault on Freedom of Movement. Twentieth Century Fund Report. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300044980.

- Erler, Mary C.; Kowaleski, Maryanne (2003). Gendering the Master Narrative: Women and Power in the Middle Ages. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801488306.

- Franklin, Peter (1986). "Peasant widows' "liberation" and remarriage before the Black Death". The Economic History Review. 39 (2): 186–204. doi:10.2307/2596149. JSTOR 2596149.

- Garay, Kathleen; Jeay, Madeleine (2007). "Advice concerning pregnancy and health in Late Medieval Europe: peasant women's wisdom in The Distaff Gospels". Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. 24 (1): 423–443. doi:10.3138/cbmh.24.2.423. PMID 18447313.

- Georgieva, Sashka (2003). "Marital Infidelity in Christian West European and Bulgarian Mediaeval Low (A Comparative Study)". Bulgarian Historical Review. 31 (3–4): 113–126.

- Green, Monica H. (2013). "Caring for Gendered Bodies". In Judith Bennett; Ruth Mazo Karras (eds.). Oxford Handbook of Women and Gender in Medieval Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958217-4.

- Greif, Avner (2006). "Family Structure, Institutions, and Growth: The Origin and Implications of Western Corporatism". American Economic Review. 96 (2): 308–312. doi:10.1257/000282806777212602. JSTOR 30034664. S2CID 17749879.

- Hanawalt, Barbara A. (1986). The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503649-2.

- Hanawalt, B. A. (1998). "Medieval English Women in Rural and Urban Domestic Space". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 52: 19–26. doi:10.2307/1291776. JSTOR 1291776.

- Harding, Alan (1980). "Political Liberty in the Middle Ages". Speculum. 55 (3): 423–443. doi:10.2307/2847234. JSTOR 2847234. S2CID 153735882.

- Heather, Peter J. (1999). The Visigoths from the Migration Period to the Seventh Century: An Ethnographic Perspective. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0851157627. OCLC 185477995.

- Levin, Eve (1995). Sex and Society in the World of the Orthodox Slavs, 900-1700. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801483042.

- McDougall, Sara (2013). "Women and Gender in Canon Law". In Judith Bennett; Ruth Mazo Karras (eds.). Oxford Handbook of Women and Gender in Medieval Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 163–178. ISBN 978-0-19-958217-4.

- Middleton, Chris (1981). "Peasants, patriarchy and the feudal mode of production in England: 2 Feudal lords and the subordination of peasant women". Sociological Review. 29 (1): 137–154. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954x.1981.tb03026.x. S2CID 144572779.

- Mitterauer, Michael (2010). Why Europe?: The Medieval Origins of Its Special Path. Translated by Gerald Chapple. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226532530.

- de Pizan, Christine (2003) [1405]. The Treasure of the City of Ladies, or The Book of the Three Virtues. Translated by Sarah Lawson. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0140449501.

- Reyerson, Kathryn (2010). Bennett, Judith M.; Mazo Karras, Ruth (eds.). Urban Economy. ISBN 978-0199582174.

{cite encyclopedia}:|work=ignored (help) - Rivers, Theodore John (1986). The Laws of Salian and Ripuarian Franks. Vol. 8. New York: AMS Press. ISBN 978-0404614386.

{cite book}:|work=ignored (help) - Schaus, Margaret C., ed. (2006). Women and gender in medieval Europe: an encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415969444.

- Shahar, Shulamith (2004). Growing Old in the Middle Ages: 'winter clothes us in shadow and pain'. Translated by Yael Lotan. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415333603.

- Thurston, Herbert (1908). "Deaconesses". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Vinogradoff, Paul (1892). Villainage in England: Essays in English Medieval History (Reissued 2010 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108019637.

- Whittle, Jane (2010). Bennett, Judith M.; Mazo Karras, Ruth (eds.). Rural Economy. ISBN 978-0199582174.

{cite encyclopedia}:|work=ignored (help) - Williams, Marty Newman; Echols, Anne (1994). Between Pit and Pedestal: Women in the Middle Ages. Markus Wiener. ISBN 978-0910129343.

Further reading

- Allen, Prudence (1997). The Aristotelian Revolution, 750BC - AD1250. The Concept of Woman. Vol. 1. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802842701.

- Green, Monica (1989). "Women's Medical Practice and Health Care in Medieval Europe". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 14 (2): 434–474. doi:10.1086/494516. PMID 11618104. S2CID 38651601.

- Gilchrist, Roberta (1996). "Gender and Material Culture: The Archaeology of Religious Women". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 6 (1): 119–136. doi:10.1017/S0959774300001621. S2CID 160573407.

- Hicks, Leonie V. (2007). Religious life in Normandy: space, gender and social pressure, c.1050–1300. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843833291.

- Wright, Sharon Hubbs. "Medieval European peasant women: A fragmented historiography." History Compass (June 2020), 18#6 pp 1–12.