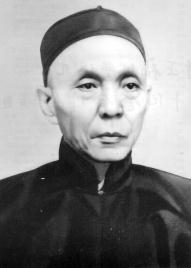

Wong Nai Siong

Wong Nai Siong | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 1849 Minqing County, Fuzhou, China | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 22 September 1924 (aged 74–75) Minqing, Fuzhou, China | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Minqing County 26°06′50.61″N 118°46′43.59″E / 26.1140583°N 118.7787750°E | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Nationality | Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Education | scholar | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation(s) | revolutionary leader, educator | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Tongmenghui | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | First wife - Mdm Xie; Second wife - Mdm Qian | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Relatives | Wong Nai Muo (younger brother), Lim Boon Keng (son-in-law), Wu Lien-teh (son-in-law), Wu Weiran (son-in-law), Robert Lim (grandson) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 黃乃裳 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 黄乃裳 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Wong Nai Siong (simplified Chinese: 黄乃裳; traditional Chinese: 黃乃裳; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: N̂g Nái-siông; Bàng-uâ-cê: Uòng Nāi-siòng) (1849–22 September 1924) was a Chinese revolutionary leader and educator from Minqing county in Fuzhou, Fujian province, China. He served in The Methodist Episcopal Church for many years and participated in the "Ten Thousand Word Memorial" or the "Memorial of the Examination Candidates" Petition (Gongche Shangshu movement) in 1895.[1] He also took part in the Hundred Days' Reform in 1898[1] and the 1911 Xinhai Revolution[2] which resulted in the founding of the Republic of China. Wong led people from Fujian province to migrate to Sibu, Sarawak.[3]

Early life, conversion and education

Wong was born to Fuzhouese parents in Minqing County, Fujian Province, where his father was a carpenter.[4][5] He did farm work to help provide for his family, studying at the same time. In 1866, missionaries from the Methodist Episcopal church arrived; Wong was baptized and converted to Christianity on December the 16th that year.[6] The villagers disapproved, but didn't ostracize him, as they were from the same clan. As time went by, many villagers also converted to Christianity.

In the winter of 1867, priest Xu Yang Mei took Wong as an assistant and taught him the Bible. This led to Wong being exposed to Western culture and thinking. When asked his reason for converting to Christianity, Wong remarked on the disparity between the teachings of Confucius and the actions of those who professed Confucianism.

Imperial Examination

During his missionary time, Wong noted that few Christians lived among the influential people in the area, so he decided to take part in the Imperial Examination. In 1877, he became a scholar and was successful in obtaining the shenyuan licentiate degree.[7] His father died in 1884. In 1894, Wong graduated with a 30th position in the Imperial Examination attaining the degree of Juren.[7]

Hundred Days reform

In 1894, Wong's third brother, Wong Nai Muo (黃乃模), who served as the vice captain of the Chinese protected cruiser Zhiyuan, was killed in the First Sino-Japanese War.[8] Believing that government incompetence and corruption had led to the downfall of his country, he met Kang Youwei in Beijing and participated in the Gongche Shangshu movement in 1895.[7] In 1896, Wong founded the first modern Chinese newspaper called Fubao and advocated socio-political reform and education of the masses.[7] In 1897, he once again sat for the Imperial Exam. In 1898 following the leading reformers of the hundred days' reform, Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao, Wong submitted eight memorials for the modernization of China.[7] Wong's most well known memorial was 'petition for the Romanization of Chinese characters or Pinyin. Empress Dowager Cixi however, found these reforms far to radical and attempted to arrest the reformers and executed some of the leaders of the Reform.[7] Wong was number eleventh on the list of wanted Imperials Criminals pursued by the Qing Imperial army. He managed to escape pursuit and returned to Fujian.[7]

Reconnaissance for resettlement

In September 1899, Wong went to Singapore and worked as an editor for a local newspaper. During his stint, knowing that life was difficult for the people of Fujian, he went to Malaya, Sumatra, and the Dutch East Indies to search for locations for immigrant resettlement and escape from Empress CiXi's authoritarian rule.

In April 1900, at the recommendation of his son-in-law, Wong investigated Sarawak's Rejang River Basin. In this area with a small population and large amount of undeveloped land, immigrants were welcomed. In late May 1900, Wong, acting as the harbour master, signed a resettlement contract with the Brooke government for the Rejang Riverbanks area.

Resettlement at Sibu

In September 1900, Wong and his party started recruiting villagers to immigrate to Sibu; they were able to recruit over 500. On 23 December 1900, the first batch of 91 immigrants left for Sibu, arriving on 12 January 1901. Some of the prospective immigrants changed their minds during the journey, so only 72 people reached Sibu.

The second batch of immigrants was led by Wong personally from Fujian.[9] However, during their stop in Singapore, rumours of the villagers being sold as coolies resulted in a riot. Wong, with the help of the minister from the Methodist Episcopal Church, was able to stop the rioting. On 5 March 1901, the immigrants left Singapore; they reached Sibu eleven days later.[10]

The third batch of immigrants totalled 1118, of whom two-thirds were Christians. They reached Sibu on 7 June 1902.

Wong renamed Sibu as New Fu Zhou. He took out a loan to build six atap houses in New Zhushan to accommodate the farmers.[11] Later, he changed the name of New Zhushan to New Cuo Ann, reflecting the prosperity of the new settlement.

Wong gave each farmer 5 acres (2.0 ha) of land for farming. However, the new immigrants were not accustomed to the local climate and many fell ill. On top of that, they had to explore new techniques of farming, which made their life more difficult.

Wong established the New Fuzhou Company, which sold basic necessities, including rice and salt, to the immigrants. He built five churches and a primary school during his stint in Sibu.

During a lion dance event on the Yuan Xiao of 1930 (15 January of the Lunar Calendar), there was a gang fight between the Fuzhou immigrants and the immigrants from Guangdong. This had to be settled by Wong and the Guangdong immigrant leader. To prevent future conflicts, the Brooke government directed immigrants from Fuzhou to develop the area below Rejang Sibu.

In June 1904, Wong passed the managing duties to American minister James Hoover, and returned to Fujian. There were many rumours regarding his departure, including poor health, his yearning for revolutionary work, huge debts, and his reluctance to deal opium. After this departure, Hoover introduced rubber-tree planting; the boom in latex propelled Sibu's economy.

Return to China

In June 1906, Wong met Sun Yat-sen in Singapore and joined the Chinese Revolutionary Alliance. He started disseminating revolutionary propaganda in China, and was involved in the planning of the Chaozhou Huanggang Uprising and the promoting of Fuzhou's education and industrialisation.

Constitution revolution

In 1909, the government began promoting the establishment of a constitution. Wong was elected as a committee member for the Fujian Province. During his term, he submitted several detailed proposals regarding such matters as the establishment of a coastal police, the promotion of farming and industrialisation, and the prohibition of the sale of opium. In 1910, he became the chairman of the Fuzhou YMCA.

Resignation

In 1912, Wong quit his position due to poor health, although rumours suggested that it was due to his support for the prosecution of Pengshou Song, Secretary of the Fujian Provincial Government Administration Council (Hunan). In 1914, Yuan Shi Kai framed Wong for obstructing the "smoke ban" campaign, and he was sentenced to life imprisonment. After pressure from abroad, he was released a few months later.

Later years

In 1920, Wong was appointed the higher consultant in the Marshal Office by Sun Yat Sen. In 1921, while on leave in Fujian, he was also appointed a senior consultant in the Fujian Province Office.

In July 1923, Wong returned to Minqing County due to liver illness. He died on 22 September 1924.

After death

In China

On 13 May 1947, Fujian Province changed the name of Wang Hou Street to Nai Siong Road, to commemorate Wong's lectures in the Ming Qing Hall located on the street. The road was renamed as Shu Xin Road during the Cultural Revolution, but the name was later changed back to Nai Siong Road.

In December 1979, Ming Qing County of Fujian built a memorial museum at the Ban Tou River. A statue of Wong was erected the following year.

In 1995, the Ming Qing Ban Dong Town Lake Street was renamed "Nai Siong Street", and the Wong Nai Siong memorial museum in Ming Qing Tai Shan Park was completed.

In 1991, the graves of Wong Nai Siong and his brother Wong Nai Mo were declared provincial cultural relics. In 2001, they became a base for patriotism education.

Overseas

In 1958, Sibu Municipal named one of the streets to Nai Siong Road. On 16 March 1961, Sibu celebrated its 60th year of resettlement by unveiling the statue of Wong Nai Siong. In 1967, the "Wong Nai Siong Secondary School" was established. On 16 March 2001, Wong Nai Siong Park and Wong Nai Siong Monument were opened to the public. On 23 November 2007, during the twentieth anniversary of Hong Kong's Asia Week, Taiwanese author and Taiwan's minister of culture Lung Ying-tai mentioned Wong's accomplishments and expressed her disappointment that not many people knew of him. On 24 November 2012, during a seminar on "Wong Nai Siong and the Fujian Spirit", participants from both China and Taiwan suggested shooting a feature film about Wong. Wong's great-granddaughter Wong Bi Yao (Anne Pang) revealed that she would be meeting Lung Ying-tai in late 2012 to discuss Lung's suggestion.

Tribute

In 1950, in honor of Wong, a Sibu-based private secondary school was established and named S.M. Wong Nai Siong after him.

References

- ^ a b Pang, Anne (2011). Huang Naishang: a Chinese Christian reformer in late Qing and early republican China (1st ed.). Sibu, Sarawak, Malaysia: Sibu Foochow Association. pp. 43, 73. ISBN 978-983-42523-4-2. OCLC 793169651.

- ^ Pang, Anne (2011). Huang Naishang: a Chinese Christian reformer in late Qing and early republican China (1st ed.). Sibu, Sarawak, Malaysia: Sibu Foochow Association. pp. 91–117. ISBN 978-983-42523-4-2. OCLC 793169651.

- ^ Pang, Anne (2011). Huang Naishang: a Chinese Christian reformer in late Qing and early republican China. Sibu, Sarawak: Sibu Foochow Association. pp. 210–337. ISBN 978-983-42523-4-2. OCLC 793169651.

- ^ Pang, Anne (2011). Huang Naishang: a Chinese Christian reformer in late Qing and early republican China (1st ed.). Sibu, Sarawak, Malaysia: Sibu Foochow Association. p. 23. ISBN 978-983-42523-4-2. OCLC 793169651.

- ^ Lee Khoon Choy (26 March 2013). Golden Dragon And Purple Phoenix: The Chinese And Their Multi-ethnic Descendants In Southeast Asia. World Scientific. p. 462. ISBN 978-981-4518-49-9.

- ^ Pang, Anne (2011). Huang Naishang: a Chinese Christian reformer in late Qing and early republican China (1st ed.). Sibu, Sarawak, Malaysia: Sibu Foochow Association. p. 24. ISBN 978-983-42523-4-2. OCLC 793169651.

- ^ a b c d e f g Pang, Anne (2011). Huang Naishang: a Chinese Christian reformer in late Qing and early republican China (1st ed.). Sibu, Sarawak, Malaysia: Sibu Foochow Association. pp. 40–79. ISBN 978-983-42523-4-2. OCLC 793169651.

- ^ Government of Fuzhou (2 March 2022). 北洋海军将领黄乃模与甲午中日海战 (in Chinese).

- ^ Patricia Pui Huen Lim; Chong Guan Kwa; James H. Morrison (1998). Oral History in Southeast Asia: Theory and Method. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 127. ISBN 978-981-230-027-0.

- ^ David W. Scott (26 July 2016). Mission as Globalization: Methodists in Southeast Asia at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Lexington Books. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-4985-2664-7.

- ^ Pat Foh Chang (1999). Legends & History of Sarawak. Chang Pat Foh. pp. 212–213. ISBN 978-983-9475-06-7.