York Regional Road 1

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| York Regional Roads 1 / 51 | |||||||||

Yonge Street (Toronto/York section) | |||||||||

| Maintained by | City of Toronto York Region Town of East Gwillimbury | ||||||||

| Location | Toronto Vaughan Markham Richmond Hill Aurora Newmarket East Gwillimbury | ||||||||

| South end | Queens Quay in Toronto | ||||||||

| Major junctions | King Street Queen Street Dundas Street Bloor Street St. Clair Avenue Eglinton Avenue Lawrence Avenue Wilson Avenue / York Mills Road Sheppard Avenue Finch Avenue Steeles Avenue | ||||||||

| North end | Holland River | ||||||||

| Construction | |||||||||

| Inauguration | 1794[1] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Simcoe County Road 4 | |||||||||

Yonge Street (Simcoe section) | |||||||||

| Maintained by | Simcoe County City of Barrie | ||||||||

| Length | 30 km (19 mi)[3] | ||||||||

| Location | Barrie Bradford West Gwillimbury Innisfil Simcoe | ||||||||

| South end | 8th Line in Bradford (continues south as Barrie Street) | ||||||||

| Major junctions | |||||||||

| North end | Former Canadian National rail spur in Barrie (Continues as Burton Avenue) | ||||||||

| Construction | |||||||||

| Inauguration | 1827 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

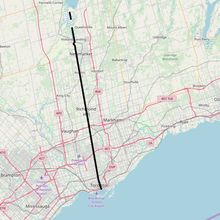

Yonge Street (/jʌŋ/ YUNG) is a major arterial route in the Canadian province of Ontario connecting the shores of Lake Ontario in Toronto to Lake Simcoe, a gateway to the Upper Great Lakes. Ontario's first colonial administrator, John Graves Simcoe, named the street for his friend Sir George Yonge, an expert on ancient Roman roads.

Once the southernmost leg of provincial Highway 11, linking the provincial capital with northern Ontario, Yonge Street has been referred to as "Main Street Ontario". Until 1999, the Guinness Book of World Records repeated the popular misconception that Yonge Street was 1,896 km (1,178 mi)[4] long, making it the longest street in the world; this was due to a conflation of Yonge Street with the rest of Ontario's Highway 11. The street (including the Bradford-to-Barrie extension) is only 86 kilometres (53 mi) long.[2][3] Due to provincial downgrading in the 1990s, no section of Yonge Street is marked as a provincial highway.

Its construction has been designated as an Event of National Historic Significance in Canada.[5] Yonge Street was integral to the original planning and settlement of western Upper Canada in the 1790s, forming the basis of the concession roads in Ontario today. In Toronto and York Region, Yonge Street is the north–south baseline from which street numbering is reckoned east and west. The eastern branch of the subway Line 1 Yonge–University serves nearly the entire length of the street in Toronto; it serves as the spine of the Toronto subway system, linking to suburban commuter systems such as the Viva Blue BRT. The street is a commercial main thoroughfare rather than a ceremonial one, with the Downtown Yonge shopping and entertainment district containing landmarks such as the Eaton Centre and Yonge–Dundas Square.

Route description

Yonge Street originates on the northern shore of Toronto Bay at Queens Quay as a four-lane arterial road (speed limit 40 km/h) proceeding north. Toronto's Harbourfront is built on landfill extended into the bay. The former industrial area has been converted from port, rail and industrial uses to a dense, residential, high-rise community. The elevated Gardiner Expressway and the congested rail lines of the Toronto railway viaduct on their approach to Union Station pass over Yonge Street. The road rises slightly near Front Street, marking the pre-landfill shoreline. Here, at the southern edge of the central business district, is the Dominion Public Building, the Meridian Hall and the Hockey Hall of Fame, the latter housed in a former Bank of Montreal office, once Canada's largest bank branch. Beyond Front Street, the road passes through the east side of the Financial District, which holds many of Canada's tallest buildings, and passes an entrance to the Allen Lambert Galleria.

Between Front and Queen Streets, Yonge Street is bounded by historic and commercial buildings, many serving the large weekday workforce concentrated here. These include the flagship Toronto locations of the Hudson's Bay Company and Saks Fifth Avenue, both in the historic Simpson's building. Yonge Street's entire west side, from Queen to Dundas Streets, is occupied by the Eaton Centre, a multi-storey indoor mall featuring shops along its Yonge Street frontage. The east side has two historic performance venues, the Ed Mirvish Theatre (formerly the Canon Theatre and before that, the Pantages) and the Elgin and Winter Garden Theatres. In addition, Massey Hall is just to the east on Shuter Street.

Opposite the north end of the Eaton Centre lies Yonge–Dundas Square. The area now comprising the square was cleared of several small commercial buildings and redeveloped in the late 1990s and early 2000s. It has been outfitted with large video screens, and developed with retail shopping arcades, fountains and seating in a bid to become "Toronto's Times Square". It is the site of numerous public events.

Another stretch of busy retail lines both sides of Yonge Street north of Dundas Street. The density of businesses diminishes north of Gerrard Street; residential towers with some ground-floor commercial uses flank this section. The Art Deco College Park building, a former shopping complex of the T. Eaton Company, occupies much of the west side of the street from Gerrard Street north to College Street. It was converted into a residential and commercial complex after the building of the Eaton Centre.

From College Street north to Bloor Street, Yonge Street serves smaller street-level retail, mostly in two- to three-storey buildings of a hundred years' vintage. The businesses here, unlike the large chains that dominate south of Gerrard Street, are mostly small independent shops and serve a dense residential community on either side of Yonge Street.

The intersection of Yonge and Bloor streets is a major crossroads of Toronto, informally considered the northern edge of the downtown core. Subway Line 2 Bloor–Danforth intersects the Yonge line here, with the resulting transfers between lines making Bloor–Yonge station the busiest in the city. The northeast quadrant features the Hudson's Bay Centre office and retail complex, including a Hudson's Bay Company Hudson's Bay store. The northwest quadrant has the Two Bloor West office tower. The southeast quadrant has a condominium tower constructed in the early 21st century, and the southwestern quadrant is being developed for a condominium. The Mink Mile's borders extend from Yonge to Avenue Road along Bloor. The intersection of Yonge and Bloor streets is a "scramble"-type intersection, which allows pedestrians to cross from any corner to any other corner.

Immediately north of Bloor, the street is part of the old town of Yorkville, today a major shopping district extending west of Yonge Street along Cumberland and Bloor streets. North of Yorkville, densities and traffic decrease somewhat and the speed limit increases slightly (to 50 km/h, which it remains for most of its urban length) as Yonge Street forms the main street of Summerhill, which together with Rosedale to the east is noted for its opulent residences. The area is marked by the historic North Toronto railway station, formerly served by the Canadian Pacific Railway and now the location of an Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO) store. The CPR route parallels the foot of the Iroquois shoreline escarpment, which Yonge Street ascends here toward Midtown. Development along Yonge to St. Clair Avenue is mostly two- and three-storey buildings with ground-floor commercial uses of varying types. South of St. Clair once stood the Deer Park carhouse for the Metropolitan Street Railway Metropolitan line. It was sold by the Toronto Transportation Commission to the Badminton and Racquet Club of Toronto in 1924 and mostly destroyed by a fire in 2017.

From approximately St. Clair Avenue to Yonge Boulevard, Yonge Street is central to the former suburb municipality of North Toronto, now widely referred to as Midtown, which is divided into several local neighbourhoods. Yonge Street along this stretch features mixed low-scale residential, retail, and commercial buildings. The intersection at Eglinton Avenue has become a focal point, serving as a high-density residential, commercial and transit hub. The site of Montgomery's Tavern is nearby,[6] the location of a significant clash in the Upper Canada Rebellion and is marked as a National Historic Site. The tavern was later replaced by the Postal Station K Building, now a podium for Montgomery Square condominium complex.

North of Yonge Boulevard, Yonge Street traverses the deep forested ravine of the West Don Valley at Hoggs Hollow, a formidable obstacle in pioneer days and the site of one of the last of the former toll gates. The lower-density residential community and park-like setting here represent an interlude between North Toronto and the newer high-rise district beyond, towering over the valley. Canada's busiest section of highway (Highway 401) spans the valley via the Hogg's Hollow Bridge (exit 369). Leaving the valley north of Highway 401, densities and traffic both significantly increase on entering North York City Centre, the downtown core of the former suburban city of North York. North York Centre features numerous residential and office towers, most with ground-floor commercial uses, with some stretches of older two-storey buildings, many slated for redevelopment. Slightly under halfway up Yonge Street from Sheppard to Finch on the west side is the North York Civic Centre complex and the adjacent North York Centre office and retail towers. These lands contain Mel Lastman Square, the actual North York district municipal offices, the North York Central Library and the Toronto Centre for the Performing Arts. The street widens to a six-lane urban arterial road through North York Centre (although north of Sheppard Avenue the outer lanes are for parking outside of rush hours), passing inner-suburb transit hubs at Sheppard and Finch Avenues.

From Finch Avenue to Stouffville Road (acquiring the York Regional Road 1 designation north of the Toronto city limits at Steeles Avenue in York Region), Yonge Street is a suburban commercial strip, passing Highway 407 (exit 77) two kilometres north of Steeles. This 16.5 km (10.3 mi) segment is a busy suburban arterial, interrupted by the original town centres of suburban communities such as Thornhill (where the route crosses the East Don Valley in the upper part of its watershed) and Richmond Hill. Various stretches of Yonge Street throughout this area contain residential high-rise buildings of varying ages, with some currently under development. Continuous urbanization ends just south of Stouffville Road, and the street passes through brief semi-rural exurban stretches between Richmond Hill, Aurora, Newmarket, and Holland Landing, passing a number of kettle lakes and traversing the crest of the Oak Ridges Moraine, thence leaving the Lake Ontario basin. Yonge passes through the core of Aurora, and in the regional seat of Newmarket, Yonge serves as the town's main suburban artery, passing through low-density residential and commercial areas, bypassing its core to the west. North of Green Lane, Regional Road 1 deviates from the original baseline 56 km (35 mi) north of Lake Ontario, bypassing the centre of Holland Landing with a northwest heading and thereby circumnavigating Cook's Bay and the lower Holland Marsh, through exurban areas en route to Bradford. The bypass was constructed in 1959.

York Regional Road 51

Regional Road 51 is the original route of the main section. Yonge Street branches off Regional Road 1 at the foot of the bypass to continue north through Holland Landing. This short section, known locally as the Yonge Street Extension, is co-signed with Regional Road 13. At Queensville Side Road, the road breaks, and resumes again slightly to the west for 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) before it ends in the upper Holland Marsh with an unopened road clearance signed with trees next to the Silver Lakes Golf and Country Club.

Simcoe Road 4

Yonge resumes to the northwest in Bradford (reached via Regional Road 1), at a right turn at an intersection in downtown Bradford, where it is initially named Barrie Street before the name Yonge resumes, roughly paralleling Lake Simcoe's western shore through rural countryside, traversing the rolling hills of southeast Simcoe County, and is signed Simcoe Road 4. The street officially ends in Barrie at a rail spur, where its name changes to Burton Avenue at Garden Drive, which itself ends less than a kilometre from Kempenfelt Bay, at a T-intersection with Essa Road.

History

Establishment of the route

With the outbreak of hostilities between France and Great Britain in 1793, part of the War of the First Coalition, the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada (now Ontario), John Graves Simcoe, was concerned about the possibility of the United States entering British North America in support of their French allies. In particular, the location of Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake), the first and former capital of Upper Canada, was in danger of being attacked by the Americans from the nearby border. Additionally, U.S. forces could easily sever British access to the upper lakes at Lake St. Clair or the Detroit River, cutting the colony off from the important trading post at Michilimackinac.

Simcoe planned to move the capital to a better-protected location and build overland routes to the upper lakes as soon as possible. He established York, as Toronto was originally called, with its naturally enclosed harbour, as a defensible site for a new capital. To provide communications between the site and the upper lakes, he planned two connected roads, the first running north from York to Lake Simcoe, (then named Lake aux Claies), the second joining Lake Simcoe with Georgian Bay. This would allow overland transport to the upper lakes, bypassing U.S. strongholds. The route from Lake Ontario to Lake Simcoe is still known as Yonge Street, and the second leg to Georgian Bay was long known as the Penetanguishene Road.

Before the construction of Yonge Street, a portage route, the Toronto Carrying-Place Trail, had already linked Lakes Ontario and Simcoe. On September 25, 1793, Simcoe and a small party of soldiers and native guides started northward along the trail, establishing the Pine Fort on the western branch of the Holland River, near the modern location of Bradford. Stopping only to rename Lake aux Claies "Lake Simcoe" in memory of his father, the party continued north to Lake Couchiching, and then down the Severn River to Georgian Bay. Here he selected the site of Penetanguishene as the location for a new naval base and port.

On his return, he met with an Ojibway named 'Old Sail' and was shown a new route along another arm of the trail, this one starting on the eastern branch of the Holland River and thereby avoiding the marshes of the western branch (today's Holland Marsh). They left Pine Fort on October 11 and reached York on the 15th. Simcoe selected this eastern route for his new road, moving the southern end from the Rouge River to the western outskirts of the settled area in York, and the northern end to a proposed new town on the Holland River, St. Albans.[7]

The road was actually called Concession 1 at first with Concessions 2 etc. on either side. For instance Concession 1 Whitchurch Township faces Yonge St. and goes east to Concession 2, which starts at Bayview Ave. Concession 1 King Township faces Yonge St. and goes west to Concession 2, which starts at Bathurst St. There are 10 concessions in York County going east and west from Concession 1, Yonge Street. The east side ending at then-Ontario County, now Durham Region, and the west side ending at Peel County (now Peel Region).

Construction of Yonge Street

The following spring, Simcoe instructed Deputy Surveyor General Augustus Jones to blaze a small trail marking the route.[8][9]

Simcoe initiated construction of the road by granting land to settlers, who in exchange were required to clear 33 feet of frontage on the road passing their lot. Certain seasons saw the muddy sidewalks of York in deplorable condition, and Yonge Street was renowned as being particularly bad, making it difficult to transport loads along it. The first Toronto resident known to have introduced sidewalks was Jesse Ketchum, who used tanned bark.[10]

In the summer of 1794, William Berczy was the first to take up the offer, leading a group of 64 families northeast of Toronto to found the town of German Mills, in modern Markham. By the end of 1794, Berczy's settlers had cleared the route around Thornhill. However, the settlement was hit by a series of setbacks and road construction stalled.

Work on the road started again in 1795 when the Queen's Rangers took over. They began their work at Eglinton Avenue and proceeded north, reaching the site of St. Albans on 16 February 1796. Expansion of the trail into a road was a condition of settlement for farmers along the route, who were required to spend 12 days a year to clear the road of logs, subsequently removed by convicted drunks as part of their sentences. The southern end of the road was in use in the first decade of the 19th century, and became passable all the way to the northern end in 1816.[11]

The road was extended south from Eglinton to Bloor Street in 1796 by Berczy, who needed a route to his warehouse on the Toronto lakeshore. The area south of Bloor Street proved too swampy for a major road. A path did exist between Queen and Bloor Streets, but was called the "road to Yonge Street", rather than being considered part of the street itself due to its poor condition. Over time the creeks were rerouted and the swamps drained. In 1812 the route was extended from Queen Street to the harbour, and in 1828 the entire southern portion was solidified with gravel.[12]

St. Albans never developed as Simcoe had hoped, but the town of Holland Landing eventually grew up on the site, a somewhat more descriptive name. Holland Landing was settled by Quakers who moved into the area after having left the United States in the aftermath of the American Revolution. The settlers were branching out from their initial town of "Upper Yonge Street", which later became Newmarket.

The road almost served its original military purpose during the War of 1812, when construction of a new fleet of first-rate ships began on the Lakes, necessitating the shipment of a large anchor from England for use on a frigate under construction on Lake Huron. The war ended while the anchor was still being moved, and now lies just outside Holland Landing in a park named in its honour.

Evolution of Yonge Street

Bears were known to wander onto Yonge Street in the early days of Toronto. In 1809 Lieutenant Fawcett, of the 100th Regiment, came across a large bear on the street and cut its head open with his sword.[13]

In 1824, work began to extend Yonge Street to Kempenfelt Bay near Barrie. A northwestern extension was branched off the original Yonge Street in Holland Landing (present-day Holland Landing Road and the stretch of York Road 1 running northwest of Bathurst Street) and ran into the new settlement of Bradford before turning north towards Barrie (with the Bradford-Barrie stretch being the only part of the later Highway 11 apart from the original section ever to be named Yonge). Work was completed by 1827, making connections with the Penetanguishene Road.[citation needed] In 1833, the legislature voted to "macadamise" some portions of the dirt road.[14]

The decision was made to withdraw the military garrison in Penetanguishene in 1852. A year later, the Northern Railway of Canada was built along this established route, between Toronto and Kempenfelt Bay and extended to Collingwood by 1855. Settlement along the Penetanguishene Road pre-dated the road itself. Subsequent extensions of Yonge Street (though never named as such) which later became the more northerly parts of Highway 11, built in the 1830s (some with military strategy in mind), pushed settlement northeast along the shores of Lake Simcoe. By 1860 the Muskoka Road penetrated the southern skirts of the Canadian Shield, advancing towards Lake Nipissing.

The government of Upper Canada had a limited tax base and a vast area to settle, so they asked private individuals to build and maintain roads in exchange for the right to toll wayfarers.[14][15][16][17] This was a commonplace arrangement at the time: For example, a 13-km stretch of Davenport Road between the Humber River and the Don River had no less than five tollbooths spaced along its length.[15] In the 1830s, the tollbooth near York Mills' Miller Tavern and north of Montgomery's Tavern was "a tiny two-storey building on the west side of Yonge" at the top of the hill "with a roof stretched over the roadway to a support on the far side."[16]

In 1850, Yonge Street together with a number of other local roads was purchased at auction by James Beatty and his Toronto Road Company for £75,100. Beatty was out of pocket in September 1863, and the legislature once more assumed control until April 1865, when it was able to pass control (also at auction) to York County Council for $72,500.[14]

The tolls in effect in 1875 ranged from 1 cent for each pig, sheep, or goat to 10 cents for every vehicle with a load drawn by a horse. The tolls were designed to tax those that had money: Farmers on their way to market.[18]

A horse-drawn streetcar line was completed on Yonge Street in Toronto in September 1861 and operated by the Toronto Street Railway.[19] The line went from Scollard Street to King Street.[20] Streetcar service would be electrified in Toronto by 1892.

Confederation and the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway further diminished the importance of Yonge Street, as the new Dominion of Canada heralded the construction of east–west trade routes spanning the continent. By the 1870s, Henry Scadding, author of Toronto of Old, declared that Penetanguishene did not have the importance to need an approach such as the "extension of the Yonge Street Road."

During the late 1800s, the Toronto and York Radial Railway used the Yonge Street right-of-way, originally to the town of North Toronto, but expanding over the years all the way to Sutton, on southern Lake Simcoe.[21] The Radial Railway ran along the eastern side of the street, allowing the prevailing westerly winds to remove snow from the slightly raised rails. The arrival of the Canadian Northern Railway in 1906 lessened traffic on the Radial, but it was not until Yonge became a major route for cars that the Radial truly fell into disuse. The last TYRR train north from Toronto ran on March 16, 1930. The line was then purchased by the townships north of the city and re-incorporated as North Yonge Railways, running service for another eighteen years before operations ended, along with service on numerous other portions of the Radial lines, in 1948. The space it formerly occupied was used to expand the road between Aurora and Newmarket.

Canada's first Subway

From the early 1900s onwards, there were several proposals to build a subway for streetcars on Yonge Street, given the high demand for north–south travel within downtown Toronto.[22][23] Following World War 2, the Toronto Transit Commission proposed a north–south subway line along the Yonge Street corridor between Union Station and Eglinton Avenue.[24] Approved by voters in 1946, construction began in September 1949, with disruptive cut-and-cover construction on Yonge Street taking place between College Avenue and Front Street.[25][22] The Yonge Subway was opened in 1954 as Canada's first subway line at a cost of $59m.[26] The line has subsequently been extended several times, most recently to Vaughan, York Region in 2017.[27] The line – now Line 1 Yonge–University – is the busiest subway line in Canada, and one of the busiest in North America.[28]

Yonge Street as the "longest street in the world"

Yonge Street was formerly a part of Highway 11, which led to claims that Yonge Street was the longest street in the world.[29] Running (mostly) concurrent with Yonge as far north as Barrie, then continuing beyond through central and northern Ontario to the Ontario-Minnesota border at Rainy River, the highway was over 1,896 kilometres (1,178 mi) long. But Yonge Street could only be called the longest street in the world if it were fully synonymous with Highway 11 over the highway's entire length, which has never been the case.[30]

The original historic alignment of Yonge Street diverges from the former Highway 11 (now York Regional 1) in East Gwillimbury, one kilometre north of Green Lane; at this junction, York Road 1 diverts northwest, while Yonge Street turns right at the intersection and then loops back to continue the straight alignment. It then continues, ending at Queensville Side Road in Holland Landing. Approximately 350 metres further west at a jog, it runs north for about 1.8 kilometres, stopping at a dead end just past the Silver Lakes Golf and Country Club; further north, the name picks up again as an unpaved farm road which ends at Ravenshoe Road west of Keswick and just south of Lake Simcoe.[30] The diversion running from Holland Landing to Bradford does not carry the Yonge name but instead was named Bradford Street in Holland Landing, and Holland Landing Road in Bradford. The latter was later extended as a bypass was added, curving off the original alignment. A second bypass was later constructed, bypassing the entirety of Holland Landing Road and joining Bradford at Bridge Street. At its intersection with 8th Line in Bradford, the former Highway 11 route does pick up the name Yonge again (the only stretch of the former highway aside from the original Yonge Street to carry it), retaining it through Innisfil until transitioning into Burton Avenue in the Allandale neighbourhood of Barrie, which ends shortly after at Essa Road.

From that point, no other part of the highway any further north ever carried the Yonge Street name, and it makes several turns in Barrie itself as it follows various streets. At its terminus in Rainy River, Highway 11's street name is Atwood Avenue rather than Yonge Street.[31] When the final leg of Highway 11 between Atikokan and Rainy River was completed in 1965, the Rainy River Chamber of Commerce responded with a publicity stunt requesting that Toronto change the name of Yonge Street to Atwood Avenue so that the highway could have the same street name at both ends, but this did not occur.[32]

The claim was first added by the Guinness Book of Records in 1977 at the request of Toronto writer Jay Myers, supplanting Figueroa Street in Los Angeles.[33] Myers had sought the designation after writing and publishing a book about the history of the street.[33] Earlier claims that Yonge was the longest street in the world also existed, with The Globe asserting it about the original Toronto to Lake Simcoe alignment in 1895, at a time when the rest of Highway 11 did not even exist yet,[34] and later claiming in 1953 that Yonge was the longest street in the world because it purportedly extended to Cochrane, which was then and still is the point at which Highway 11 switches from a north–south alignment to an east–west alignment toward Nipigon.[35] It continued to be listed by Guinness until 1999, when it was dropped in favour of recognizing the Pan-American Highway as the world's longest motorable road.[29]

Provincial downloading separated Yonge Street from Highway 11 in the late 1990s.[36] As a result, Highway 11 does not start until Crown Hill just outside Barrie, several kilometres north of where the name Yonge Street ends.[30]

Although current tourist campaigns do not make much of Yonge Street's length, its status as an urban myth was bolstered by an art installation at the foot of Yonge Street and a map of its purported length laid out into the sidewalk in bronze at the southwest corner of Yonge and Dundas Streets.[30] However, possibly due to wider recognition of the street's actual length, the map inlay has now been removed.

Interestingly, the true longest named street in the world may be another street originating in Toronto; Dundas Street. It runs west from the city (crossing Yonge) to London, Ontario; with that name throughout most of its length, including at both ends. It was conceived and constructed as a single street, although it has several bypasses and discontinuous sections today.[37]

2000s

In 2008, Toronto's first pedestrian scramble was opened at the intersection of Yonge and Dundas Streets.

On April 23, 2018, a driver intentionally struck numerous pedestrians, killing 11 and injuring 15 others. The attack started at the intersection of Yonge Street and Finch Avenue and proceeded south along the sidewalks of Yonge Street to near Sheppard Avenue.[38][39]

Cultural significance

As Toronto's main street, Yonge hosts parades, street performances, and protests. After major sporting victories thousands of people will gather on its downtown portions, particularly near Dundas Square, to celebrate, and the street will be closed to vehicular traffic. Streetcars on routes crossing Yonge in that area (Carlton, Dundas, Queen, King) during those celebrations will often have to cease operations a few hundred metres east or west of Yonge Street due to the crowds. In recent times, these celebrations particularly occurred after the Toronto Blue Jays won the World Series of Baseball in 1992 and 1993, when the Canada men's national ice hockey team won the Olympic gold medal in 2002, 2010 and 2014, and when the Toronto Raptors won the NBA championship in 2019. During these celebrations motorists drive up and down the other portions of the street honking their horns and flying flags and during lesser celebrations (when the crowds have not closed down the street), they will do this along the downtown portions of the street as well.

Sections of the street are often closed for other events, such as an annual street festival. In 1999 Ricky Martin held an autograph session at Sunrise Records and had a large section of the street closed for the day.[40] The intersection of Yonge and Dundas Streets, centred on the plaza at Yonge-Dundas Square, has been closed on occasion to host free concerts, including performances by R.E.M. on 17 May 2001, by Beyoncé on 15 September 2006 and by John Mayer on 16 September of the same year.

Five-pin bowling was invented and first played at the Toronto Bowling Club at Yonge and Temperance Streets.

Ken Westerfield and Jim Kenner are credited with introducing ultimate and other disc sports (frisbee) to Canada. They did nightly Frisbee shows on the Yonge Street Mall between Gerrard and Dundas in 1971–1974.[41][42]

Toronto's annual LGBTQ Pride, Orange Order,[43] and Santa Claus parades also use Yonge Street for a significant portion of their routes.

Cultural references

The early works of Canadian singer-songwriters such as Joni Mitchell and Gordon Lightfoot were featured at the Yonge Street location of Sam the Record Man, just north of Dundas Street, at a time when records by Canadian musicians were not widely available. Lightfoot has a song about Yonge Street, titled "On Yonge Street," on his album A Painter Passing Through.

Yonge Street was also the subject or setting for an SCTV comedy sketch featuring John Candy, Joe Flaherty, Andrea Martin, and Jayne Eastwood. The sketch, Garth & Gord & Fiona & Alice, was a parody of the Canadian film Goin' Down the Road, about young men from the provinces discovering the bright lights of Yonge Street.

The Canadian singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn makes this reference in his song "Coldest Night of the Year," in his 1981 album Mummy Dust: "I took in Yonge Street at a glance / Heard the punkers playing / Watched the bikers dance / Everybody wishing they could go to the south of France / And you're not here / On the coldest night of the year."

Singer and rapper K-os also references the street in the lyrics of his 2004 single "Crabbuckit": "Walking down Yonge Street on a Friday / Can't follow them, gotta do it my way / No fast lane, still on a highway".

Public transit

In Toronto, Yonge Street is served by the eastern half of the Line 1 Yonge–University subway, which runs north from Union Station at Front Street to Finch Avenue. The first section of the "Yonge subway" opened in 1954 as Canada's first subway line, and is now the busiest rapid transit route in Canada, and one of the busiest in North America.[28] There is also a supplementary bus route running along the street, as well as an overnight Blue Night bus route which operates after the subway closes.

In York Region, the street is served by Viva Blue, a bus rapid transit route which connects with Finch station at the northern terminus of the subway. The subway is proposed to be extended north to Highway 7 in Richmond Hill, and the construction of dedicated bus lanes called rapidways for the Viva buses is underway as of 2017 from Highway 7 to Major Mackenzie Drive. Viva Blue is also supplemented by two local-service routes. In Holland Landing, there are transit services as well. In Simcoe County, GO Transit runs a bus route along Yonge from Newmarket to Barrie. Barrie Transit operates Route 8 (8A RVH/Yonge and 8B Crosstown/Essa), a circular route with directional branches that serve Yonge for a portion of their respective routes.

The trunk routes serving the street are:

Toronto (TTC):

| Route | Direction and Termini | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yonge–University | SB | To Union Station (Front Street) Line continues northwest to Vaughan Metropolitan Centre station |

NB | To Finch Avenue |

| 97A | Yonge | SB | To Davisville station | NB | To York Mills station |

| 97B | Yonge | SB | To Queens Quay | NB | To York Mills station |

| 97F | Yonge | SB | To Davisville station | NB | To Steeles Avenue |

| 320 | Yonge (Blue Night) |

SB | To Queens Quay | NB | To Steeles Avenue |

York Region (YRT):

| Route | Direction and Termini | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viva Blue | SB | To Finch Bus Terminal | NB | To Newmarket Bus Terminal (Davis Drive) | |

| 99 | Yonge South[44] | SB | To Finch GO Bus Terminal | NB | To Bernard Terminal (north of Elgin Mills Road) |

| 98 | Yonge North | SB | To Bernard Terminal | NB | To Green Lane |

| 52 | Holland Landing[45] | SB | To Newmarket Terminal | NB | To Queensville Sideroad Loops back south via other streets in Holland Landing to terminate back at the Newmarket Terminal |

Simcoe County (GO Transit):

| Route | Direction and Termini | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 68 | Barrie[46] | SB | To Newmarket Terminal | NB | To Barrie Bus Terminal via Toll Gate Road |

Barrie (Barrie Transit):

| Route | Direction and Termini | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8A | RVH/Yonge[47] | SB | To Mapleview Drive Clockwise branch serves Yonge between Essa Rd. and Mapleview Dr. | NB | To Royal Victoria Hospital via off-Yonge St. routing |

| 8B | Crosstown/Essa | SB | To Mapleview Drive via off-Yonge St. routing | NB | To Royal Victoria Hospital Counterclockwise branch serves Yonge between Mapleview Dr. and Essa Rd. |

Major junctions

| City | Km | Mi | Road | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto | 0.0 | 0.0 | Queens Quay | |

| 0.3 | 0.1 | |||

| 0.6 | 0.4 | Front Street | ||

| 0.8 | 0.5 | King Street | ||

| 1.2 | 0.8 | Queen Street | ||

| 1.7 | 1.0 | Dundas Street | ||

| 3.3 | 2.1 | Bloor Street | ||

| 5.4 | 3.3 | St. Clair Avenue | ||

| 7.5 | 4.6 | Eglinton Avenue | ||

| 9.5 | 5.9 | Lawrence Avenue | ||

| 11.7 | 7.3 | Wilson Avenue / York Mills Road | ||

| 12.7 | 7.9 | Highway 401 exit 369 | ||

| 13.7 | 8.5 | Sheppard Avenue | ||

| 15.7 | 9.8 | Finch Avenue | ||

| Markham – Vaughan – Toronto tripoint | 17.8 | 11.1 | Steeles Avenue | |

| Vaughan – Markham boundary | 19.8 | 12.3 | Centre Street | |

| Markham – Vaughan – Richmond Hill tripoint | 21.9 | 13.6 | Highway 407 exit 77 | |

| Richmond Hill | 22.1 | 13.7 | ||

| 24.0 | 14.9 | |||

| 26.0 | 16.2 | |||

| 28.1 | 17.5 | |||

| 32.2 | 20.0 | |||

| 34.3 | 21.3 | |||

| Richmond Hill – Aurora boundary | 36.4 | 22.6 | ||

| Aurora | 40.5 | 25.2 | ||

| Newmarket | 46.8 | 29.1 | ||

| East Gwillimbury | 49.88 | 31.0 | Former Highway 11 | |

| 55.3 | 34.4 | Continues north 0.2 km east along Queensville Sideroad | ||

| 57.1 | 35.5 | Dead end |

See also

References

- ^ the Historical Committee (1984). "Main Street, Ontario". From Footpaths to Freeways. Ontario Ministry of Transportation and Communications. p. 23. ISBN 0-7743-9388-2.

- ^ a b "Toronto Neighborhoods". Boldts.net.

- ^ a b Google (March 21, 2018). "Yonge Street route Simcoe County & Barrie" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ Young, Mark C. (1999). Guinness Book of World Records. Bantam. ISBN 0-553-58075-2. Retrieved February 16, 2010.

- ^ Construction of Yonge Street National Historic Event – Directory of Designations of National Historic Significance of Canada

- ^ http://wholemap.com/map/area.php?area=NorthToronto&pin=RHPL-1[dead link]

- ^ "Early Days in Richmond Hill: A History of the Community to 1930 : electronic edition. : The Road through Richmond Hill". edrh.rhpl.richmondhill.on.ca.

- ^ Mike Filey (1997). Toronto Sketches 5: The Way We Were. Dundurn Press. p. 96. ISBN 9781459713307. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

augustus jones yonge.

- ^ "The Road through Richmond Hill". Richmond Hill Public Library. Archived from the original on 2001-10-29. Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- ^ Peppiatt, Liam. "Chapter 16: The Children's Friend". Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto Revisited. Archived from the original on 2018-09-22. Retrieved 2015-07-09.

- ^ "Yonge Street's History". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ McHugh, Patricia. Toronto Architecture. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1989 pg. 60

- ^ Peppiatt, Liam. "Chapter 19: A Sketch of the Grange". Robertson's Landmarks of Toronto Revisited.

- ^ a b c Stamp, Robert M. (1991). "Chapter 6 Stagecoach Lines and Railway Tracks". Early Days in Richmond Hill: A History of the Community to 1930 (electronic ed.). Richmond Hill Public Library Board.

- ^ a b Mayers, Adam (24 March 2008). "When Yonge was a toll road". Toronto Star Newspapers Ltd.

- ^ a b SCHLEE, GARY (13 February 2021). "1837, Yonge Street, Never Popular as a Toll Road". Bedford Park Residents Organization.

- ^ "The Tollkeepers Cottage and Early Roads". P.J. Hare and The Toronto Green Community. Lost Rivers. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- ^ Hutcheson, Stephanie (1978). "Toll Gate at Yonge & Bloor". Toronto Public Library.

- ^ Filey, Mike (2001). A Toronto Album: Glimpses of the City that Was. Toronto: Anthony Hawke (The Dundurn Group). p. 9. ISBN 9780888822420. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- ^ "Toronto History FAQs". City of Toronto Archives. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- ^ "Early Days in Richmond Hill: A History of the Community to 1930 : electronic edition. : Rails through Richmond Hill". edrh.rhpl.richmondhill.on.ca.

- ^ a b "A Cavalcade of Progress, 1921–1954". Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ Toronto, City of (2017-11-23). "Canada's First Subway: Why a Subway?". City of Toronto. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ James Bow, "A History of the Original Yonge Subway", December 8, 2009

- ^ "Canada's First Subway: Underground Downtown". City of Toronto. 2017-11-23. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ "1954: Toronto's subway opens – CBC Archives". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ "New $3.2B subway extension will improve 'life for hardworking people,' Trudeau says". thestar.com. 2017-12-15. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ a b Giambrone, Adam (2010-06-01). "Rocket Talk: What's the Status of the Downtown Relief Line?". Torontoist. Retrieved 2021-05-04.

- ^ a b Meri Perra, "The 'myth' of Yonge Street being the world's longest road lives on". Yahoo! News, April 14, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Sean Marshall, "The end of Yonge Street". Spacing, April 13, 2011.

- ^ Bill Taylor, "A road runs through it The far side of Rainy River is pretty well the end of the line for Yonge St.". Toronto Star, February 13, 1996.

- ^ "Rainy River Makes Unabashed Pitch for Publicity". The Sault Star, April 28, 1965.

- ^ a b Zena Cherry, "Big days for Ottawa centre". The Globe and Mail, September 2, 1977. p. 11. ProQuest 1241439869

- ^ "Toronot As It Is: A Residential and Manufacturing Centre – A Clean and Healthy City With a Vigorous Business District – A Study of Her Industries – Her Elaborate Stores and Busy Streets". The Globe, July 6, 1985.

- ^ J. A. H. Hunter, "Fun With Figures". The Globe and Mail, November 7, 1953.

- ^ Kate Harries, "Road transfers a route to chaos". The Globe and Mail, September 8, 1998.

- ^ Cohen, Ben (June 30, 2021). "'This is going to be massive': Move to replace the Dundas name causes ripples across the province". Toronto Star. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- ^ Austen, Ian; Stack, Liam (April 23, 2018). "Toronto Van Plows Along Sidewalk, Killing 10 in 'Pure Carnage'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "'A huge loss': Yonge Street van attack victim Amaresh Tesfamariam missed 'every day'". Toronto.com. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ Ricky Martin mania shuts down T.O.

- ^ "History of the TUC". Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ^ "Ken Westerfield Frisbee Pioneer". Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- ^ "186th Year for Orange Parade".

- ^ "98/99 Yonge" (PDF). Route Navigator. York Region Transit. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "52 Holland Landing" (PDF). Route Navigator. York Region Transit. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "Barrie corridor" (PDF). Maps. GO Transit. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ "Route 8 map (both branches)" (PDF). Maps. Barrie Transit. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- Bibliography

- Berchem, F. R. (1977). The Yonge Street Story (1793–1860). Toronto, ON: Natural Heritage Books.

- Magel, Ralph (1998). 200 years Yonge; a history. Toronto, ON: Natural Heritage Books.

References to old Toronto

(a) Berczy's Draft letter in the Public Archives of Canada. Among the William Berczy Papers (M.G.23, H ii, Vol.2, p. 419 and Vol. 3, p. 527). As well as agreement of the German Company reproduced in The Simcoe correspondence, I, p. 191, 192

(b) Baby collection, University of Montreal. Salso Berczy Papers National Archive.

(c) John Andre the Berczy Study Infant Toronto as Simcoe's Folly p. 137. Also see Table II that shows comparison by yearly averaged growth from 1802 to 1825 p. 138

(d) Firth, p. 10 p. 10 P.Russell to Elizabeth Russell, Sep. 1, 1793 Also in Eric ArthurToronto No Mean City" Toronto, 1964 p. 138