Zirconocene dichloride

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

|---|---|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.697 | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C10H10Cl2Zr | |||

| Molar mass | 292.31 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | white solid | ||

| Soluble (Hydrolysis) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | CAMEO Chemicals MSDS | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related compounds

|

Titanocene dichloride Hafnocene dichloride Vanadocene dichloride Niobocene dichloride Tantalocene dichloride Tungstenocene dichloride | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Zirconocene dichloride is an organozirconium compound composed of a zirconium central atom, with two cyclopentadienyl and two chloro ligands. It is a colourless diamagnetic solid that is somewhat stable in air.

Preparation and structure

Zirconocene dichloride may be prepared from zirconium(IV) chloride-tetrahydrofuran complex and sodium cyclopentadienide:

- ZrCl4(THF)2 + 2 NaCp → Cp2ZrCl2 + 2 NaCl + 2 THF

The closely related compound Cp2ZrBr2 was first described by Birmingham and Wilkinson.[1]

The compound is a bent metallocene: the Cp rings are not parallel, the average Cp(centroid)-M-Cp angle being 128°. The Cl-Zr-Cl angle of 97.1° is wider than in niobocene dichloride (85.6°) and molybdocene dichloride (82°). This trend helped to establish the orientation of the HOMO in this class of complex.[2]

Reactions

Schwartz's reagent

Zirconocene dichloride reacts with lithium aluminium hydride to give Cp2ZrHCl Schwartz's reagent:

- (C5H5)2ZrCl2 + 1/4 LiAlH4 → (C5H5)2ZrHCl + 1/4 LiAlCl4

Since lithium aluminium hydride is a strong reductant, some over-reduction occurs to give the dihydrido complex, Cp2ZrH2; treatment of the product mixture with methylene chloride converts it to Schwartz's reagent.[3]

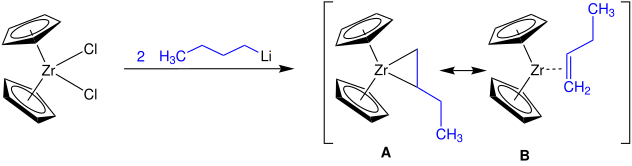

Negishi reagent

Zirconocene dichloride can also be used to prepare the Negishi reagent, Cp2Zr(η2-butene), which can be used as a source of Cp2Zr in oxidative cyclisation reactions. The Negishi reagent is prepared by treating zirconocene dichloride with n-BuLi, leading to replacement of the two chloride ligands with butyl groups. The dibutyl compound subsequently undergoes beta-hydride elimination to give one η2-butene ligand, with the other butyl ligand promptly lost as butane via reductive elimination.[4]

Carboalumination

Zirconocene dichloride catalyzes the carboalumination of alkynes by trimethylaluminium to give a (alkenyl)dimethylalane, a versatile intermediate for further cross coupling reactions for the synthesis of stereodefined trisubstituted olefins. For example, α-farnesene can be prepared as a single stereoisomer by carboalumination of 1-buten-3-yne with trimethylaluminium, followed by palladium-catalyzed coupling of the resultant vinylaluminium reagent with geranyl chloride.[5]

The use of trimethylaluminium for this reaction results in exclusive formation of the syn-addition product and, for terminal alkynes, the anti-Markovnikov addition with high selectivity (generally > 10:1). Unfortunately, the use of higher alkylaluminium reagents results in lowered yield, due to the formation of the hydroalumination product (via β-hydrogen elimination of the alkylzirconium intermediate) as side product, and only moderate regioselectivities.[6] Thus, practical applications of the carboalumination reaction are generally confined to the case of methylalumination. Although this is a major limitation, the synthetic utility of this process remains significant, due to the frequent appearance of methyl-substituted alkenes in natural products.

Zr-walk

Zirconocene dichloride together with a reducing reagent can form the zirconocene hydride catalyst in situ, which allows a positional isomerization (so-called "Zr-walk"[7]), and ends up with a cleavage of allylic bonds. Not only individual steps under stoichiometric conditions were described with Schwartz reagent,[8] and Negishi reagent,[9] but also catalytic applications on alkene hydroaluminations,[10] radical cyclisation,[11] polybutadiene cleavage,[12] and reductive removal of functional groups[13] were reported.

References

- ^ G. Wilkinson and J. M. Birmingham (1954). "Bis-cyclopentadienyl Compounds of Ti, Zr, V, Nb and Ta". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 76 (17): 4281–4284. doi:10.1021/ja01646a008.

- ^ K. Prout, T. S. Cameron, R. A. Forder, and in parts S. R. Critchley, B. Denton and G. V. Rees "The crystal and molecular structures of bent bis-π-cyclopentadienyl-metal complexes: (a) bis-π-cyclopentadienyldibromorhenium(V) tetrafluoroborate, (b) bis-π-cyclopentadienyldichloromolybdenum(IV), (c) bis-π-cyclopentadienylhydroxomethylaminomolybdenum(IV) hexafluorophosphate, (d) bis-π-cyclopentadienylethylchloromolybdenum(IV), (e) bis-π-cyclopentadienyldichloroniobium(IV), (f) bis-π-cyclopentadienyldichloromolybdenum(V) tetrafluoroborate, (g) μ-oxo-bis[bis-π-cyclopentadienylchloroniobium(IV)] tetrafluoroborate, (h) bis-π-cyclopentadienyldichlorozirconium" Acta Crystallogr. 1974, volume B30, pp. 2290–2304. doi:10.1107/S0567740874007011

- ^ S. L. Buchwald; S. J. LaMaire; R. B.; Nielsen; B. T. Watson; S. M. King. "Schwartz's Reagent". Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, vol. 9, p. 162

- ^ Negishi, E.; Takashi, T. (1994). "Patterns of Stoichiometric and Catalytic Reactions of Organozirconium and Related Complexes of Synthetic Interest". Accounts of Chemical Research. 27 (5): 124–130. doi:10.1021/ar00041a002.

- ^ "Palladium-Catalyzed Synthesis of 1,4-Dienes by Allylation of Alkenylalanes: α-Farnesene". www.orgsyn.org. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- ^ Huo, Shouquan (2016-09-19), Rappoport, Zvi (ed.), "Carboalumination Reactions", PATAI'S Chemistry of Functional Groups, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–64, doi:10.1002/9780470682531.pat0834, ISBN 978-0-470-68253-1, retrieved 2021-01-19

- ^ Sommer, Heiko; Juliá-Hernández, Francisco; Martin, Ruben; Marek, Ilan (2018-02-08). "Walking Metals for Remote Functionalization". ACS Central Science. 4 (2): 153–165. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.8b00005. ISSN 2374-7943. PMC 5833012. PMID 29532015. S2CID 4389888.

- ^ Cénac, Nathalie; Zablocka, Maria; Igau, Alain; Commenges, Gérard; Majoral, Jean-Pierre; Skowronska, Aleksandra (1996-02-20). "Zirconium-Promoted Ring Opening. Scope and Limitations". Organometallics. 15 (4): 1208–1217. doi:10.1021/om950491+. ISSN 0276-7333.

- ^ Masarwa, Ahmad; Didier, Dorian; Zabrodski, Tamar; Schinkel, Marvin; Ackermann, Lutz; Marek, Ilan (2013-12-08). "Merging allylic carbon–hydrogen and selective carbon–carbon bond activation". Nature. 505 (7482): 199–203. doi:10.1038/nature12761. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 24317692. S2CID 205236414.

- ^ Negishi; Yoshida (1980). "A novel zirconium- catalyzed hydroalumination of olefins". Tetrahedron Lett. 21 (16): 1501–1504. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(00)92757-6.

- ^ Fujita; Nakamura; Oshima (2001). "Triethylborane-Induced Radical Reaction with Schwartz Reagent". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123 (13): 3137–3138. doi:10.1021/ja0032428.

- ^ Zheng, Jun; Lin, Yichao; Liu, Feng; Tan, Haiying; Wang, Yanhui; Tang, Tao (2012-11-08). "Controlled Chain-Scission of Polybutadiene by the Schwartz Hydrozirconation". Chemistry - A European Journal. 19 (2): 541–548. doi:10.1002/chem.201202942. ISSN 0947-6539. PMID 23139199.

- ^ Matt, Christof; Kölblin, Frederic; Streuff, Jan (2019-09-06). "Reductive C–O, C–N, and C–S Cleavage by a Zirconium Catalyzed Hydrometalation/β-Elimination Approach". Organic Letters. 21 (17): 6983–6988. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02572. ISSN 1523-7060. PMID 31403304. S2CID 199539801.

Further reading

- A. Maureen Rouhi (1998). "Organozirconium Chemistry Arrives". Chemical & Engineering News. 82 (16): 162. doi:10.1021/cen-v082n015.p035.