Seldsjukkriket

| persisk: آلِ سلجوق Āl-e Saljuq[1] Seldsjukkriket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rike | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hovedstad | Nishapur (1037–1043) Rey (1043–1051) Isfahan (1051–1118) Hamadan, hovedstad i vest (1118–1194) Merv, hovedstad i øst (1118–1153) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Språk | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunniislam (Hanafi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Styreform | Monarki | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - 1037–1063 | Toghril 1. (første) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - 1174–1194 | Toghril 3. (siste)[7][8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historie | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - Grunnlagt av Toghril beg | 1037 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - Slaget ved Dandanaqan | 1040 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - Slaget ved Manzikert | 1071 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - Det første korstog | 1095–1099 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - Slaget ved Qatwan | 1141 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - Etterfulgt av Khoresm-riket[9] | 1194 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Areal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - 1080 (estimat)[10][11] | 3 900 000 km² | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I dag en del av | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Seldsjukkriket, eller Det store seldsjukkriket,[12] var et tyrkisk-persisk sunnimuslimsk rike i middelalderen,[13] med opphav i Kınık-grenen av oghuz-tyrkerne.[14] Seldsjukkriket kontrollerte et vidstrakt område, fra Hindu Kush i øst til det østre Lilleasia i vest, og fra Sentral-Asia i nord til Den persiske bukt i syd. Fra sitt hjemland nær Aralsjøen vandret først seldsjukkene inn i Khorasan, før de fortsatte videre inn i Persia, og til slutt erobret det østre Lilleasia.

Seldsjukkriket ble grunnlagt av Toghril beg (1016–63) in 1037. Toghril ble oppfostret av sin farfar, Seldsjukk beg, som hadde en høytstående posisjon i Oğuz Yabgu-riket. Seldsjukk gav sitt navn både til seldsjukkriket og seldsjukkdynastiet. Seldsjukkene forente den fragmenterte politiske scene i den østre delen av den islamske verden, og spilte en nøkkelrolle i både det første og det andre korstog. Med en meget persifisert[15] kultur[16] og språk,[17] spilte også seldsjukkene en viktig rolle i utviklingen av den tyrkisk-persiske tradisjon,[18] og medførte også eksporteringen av persisk kultur til Lilleasia.[19][20] Bosetningen av tyrkiske stammer i de nordvestre perifere delene av riket, grunnet strategiske militære behov for å bekjempe invasjoner fra nabostater, førte til den gradvise tyrkifiseringen av de områdene.[21]

Dynastiets grunnlegger

Utdypende artikkel: Seldsjukk

Seldsjukkenes felles stamfar var deres beg Seldsjukk, som angivelig skal ha tjenestegjort i khazarenes armé, og under ham skal de ha migrert til Khoresm rundt år 950, nær byen Jend, hvor de også konverterte til islam.[22]

Rikets ekspansjon

Utdypende artikler: Seldsjukk-dynastiet og Tyrkisk-persisk kultur

Seldsjukkene var alliert med de persiske samanide-sjahene mot karakhanidene. Samanidene falt til karakhanidene i Transoxania (992–999) derimot, hvoretter ghaznavidene vokste frem. Seldsjukkene involverte seg i denne regionale maktkampen før de etablerte sin egen uavhengige base.

Toghril og Tsjaghri

Utdypende artikkel: Toghril

Toghril var Seldsjukks barnebarn, og bror til Tsjaghri, hvorunder seldsjukkene frarøvet et rike fra ghaznavidene. Innledningsvis ble seldsjukkene slått tilbake av Mahmud og trakk seg tilbake til Khoresm, men Toghril and Tsjaghri ledet dem til å erobre Merv og Neyshabur i 1037.[23] Senere plyndret og byttet de landområder med hans etterfølgere på tvers av Khorasan og Balkh, og plyndret til og med Ghazni i 1037.[24] I 1040, i slaget ved Dandanaqan, påførte de et avgjørende tap på Masud I av ghaznavidene, noe som fikk ham til å gi opp mesteparten av hans vestre territorier til seldsjukkene. I 1055 erobret Toghril Bagdad fra de sjiittiske buyidene på oppdrag av abbasidene.

Alp Arslan

Utdypende artikkel: Alp Arslan

Alp Arslan, Tsjaghri Begs sønn, utvidet Toghrils rike ved erobre Armenia og Georgia i 1064, og ved å invadere Østromerriket i 1068, hvorfra han annekterte mesteparten av Lilleasia. Arslans avgjørende seier i slaget ved Manzikert i 1071 nøytraliserte nærmest all bysantinsk motstand mot den tyrkiske invasjonen av Anatolia.[25] Han gav sine turkmenske generaler lov til å skjære ut sine egne fyrstedømmer fra det tidligere østromerske Lilleasia, og regjere de som atabeger under ham. Innen to år hadde turkmenerne fått etablert kontroll på områder så lang vest som Egeerhavet, i form av en rekke beglikher (beyliker): saltukide-dynastiet i Nordøst-Anatolia, mengujekide-dynastiet i Øst-Anatolia, artukide-dynastiets i Sørøst-Anatolia, danishmende-dynastiet i Sentral-Anatolia, Rum-seldsjukkene (beghliken Suleiman, som senere flyttet til Sentral-Anatolia) i Vest-Anatolia, og beyliken Tzachas av Smyrna i İzmir (Smyrna).

Malik Shah I

Utdypende artikkel: Malik Shah I

Under Alp Arslans etterfølger, Malik Shah, og hans to persiske vesirer,[26] Nizām al-Mulk og Tāj al-Mulk, ekspanderte seldjukkriket i forskjellige retninger, til den tidligere iranske grensen før arabernes invasjon, slik at riket grenset mot Østromerriket i vest og mot Kina i øst. Malikshāh flyttet hovedstaden fra Rey til Isfahan, og det var under hans regjering at Det store seldsjukkriket nådde sitt høydepunkt.[27] Militærsystemet iqta og Nizāmīyyah Universitet ved Bagdad ble etablert av Nizām al-Mulk, og Malikshāhs regjering ble anerkjent som storseldsjukks gullalder. Abbasidekalifen gav ham tittelen «Østens og vestens sultan» i 1087. Hassan-i Sabāhs assasinere (hasjsjasjin) vokste seg derimot også mektige under hans regjering, og de snikmyrdet mange ledende skikkelser i hans administrasjon; ifølge mange kilder inkluderte offerlisten Nizām al-Mulk.

Regjering

Utdypende artikkel: Diwan#Seldsjukkene

Seldsjukkmakten nådde sitt høydepunkt under Malikshāh 1., og både karakhanidene og ghaznavidene ble tvunget til å anerkjente seldsjukkisk overherredømme.[28] Seldsjukkriket ble etablert på det gamle sasaniderikets territorium, i Iran og Irak, og inkluderte Anatolia i tillegg til deler av Sentral-Asia og dagens Afghanistan.[28] Seldsjukkstyret ble basert på en stammeorganisasjon som var vanlig blant tyrkiske og mongolske nomader, og organisasjonen liknet en «familieføderasjon», eller «apanasjestat».[28] Under denne ordningen delte overhodet av den ledende familie ut deler av sine domener som selvstyre apanasjer.[28]

Rikets oppløsning

Ved Malikshāh 1.s bortgang i 1092 ble riket delt da hans bror og fire sønner kranglet over fordelingen av riket. Malikshāh 1, ble i Lilleasia etterfulgt av Kilij Arslan 1., som grunnla Rum-sultanatet, og i Syria av hans bror Tutusj 1.. I Persia ble han etterfulgt av sin sønn Mahmud 1., hvis regjering ble utfordret av hans andre tre brødre (Barkiyaruq i Irak, Muhammad I i Bagdad, og Ahmad Sanjar i Khorasan). Da Tutusj 1. død arvet hans sønner Radwan og Duqaq henholdsvis Aleppo og Damaskus, som videre utfordret hverandre, noe som ytterligere delte Syria inn i fiendtlige emirer.

I 1118 tok Ahmad Sanjars tredje sønn over riket. Hans nevø, sønn av Muhammad 1., anerkjente derimot ikke hans krav på tronen, og Mahmud 2. erklærte seg selv sultan, og etablerte en hovedstad i Bagdad fram til 1131 da han endelig ble offisielt avsatt av Ahmad Sanjar.

Ellers i nominelt seldsjukkterritorium fantes artukidene i Nordøst-Syria og Nord-Mesopotamia; de kontrollerte Jerusalem fram til 1098. Danishmende-dynastiet grunnla en stat i Øst-Anatolia og Nord-Syria, og kjempet om landområder med Rum-sultanatet, og i tillegg nøt Kerbogha selvstendighet som Mosuls atabeg.

Det første korstog

Utdypende artikkel: Det første korstog

Under det første korstog var de splittede seldsjukkstatene generelt sett mer opptatt av å konsolidere sine egne territorier og erobre naboene enn å samarbeide mot korsfarerne. Seldsjukkene beseiret med enkelhet det utrente folkekorstoget i 1096, men de maktet ikke stoppe fremgangen til hæren til det påfølgende fyrstekorstoget, som erobret viktige byer som Nikea (İznik), Iconium (Konya), Caesarea Mazaca (Kayseri), og Antiokia (Antakya) i sitt felttog mot Jerusalem (Al-Quds). I 1099 erobret endelig korsfarerne det hellige land og etablerte de første korsfarerstatene. Seldsjukkene hadde innen denne tid allerede tapt Palestina til fatimidene, som hadde gjenerobret området kort tid før korsfarerne igjen erobret det.

Det andre korstog

Også i det andre korstog var konflikten med korsfarerstatene sporadisk, og etter det første korstog kom flere uavhengige atabeger til å alliere seg med korsfarerstatene mot andre atabeger, mens de kjempet med hverandre om landområder. I Mosul etterfulgte Zengi Kerbogha som atabeg og iverksatte en vellykket prosess med å konsolidere Syrias atabeger. I 1144 erobret Zengi Edessa, da Grevskapet Edessa hadde alliert seg med artukidene mot ham. Denne hendelsen forårsaket iverksettingen av det andre korstog. Nur ad-Din, en av Zengis sønner, som etterfulgte ham som Aleppos atabeg, stiftet en allianse i området mot korsfarerne, som ankom i 1147.

Svekkelse

Ahmad Sanjar slet med å begrense opprørene til karakhanidene opprør i Transoxiana, ghuridene i Afghanistan og qarlukkene i dagens Kirgisistan, i tillegg til karakitaienes nomadeinvasjon i øst. De fremadrykkende karakitaiene beseiret først de østre karakhanidene, før de slo ned de vestre karakhanidene, som var vasaller av seldsjukkene i Khujand. Karakhanidene henvendte seg til deres overherre seldsjukkene for å få assistanse, hvortil Sanjar svarte med å personlig lede en armé mot karakitaiene. Sanjars armé ble derimot påført et avgjørende tap av Yulu Dashis horder i slaget ved Qatwan den 9. september 1141. Selv om Sanjar maktet å flykte helskinnet ble mange i hans nære familie, inkludert hans kone, tatt til fange i kjølvannet av slaget. Som et resultat av Sanjars fiasko i å håndtere trusselen i øst mistet Seldsjukkriket alle sine østre provinser fram til elven Syr-Darja, og overherredømmet over de vestre karakhanidene ble overtatt av Kara-Kitai, også kjent som «Vest-Liao» i kinesisk historiografi.[29]

Fall til Khoresm-riket og ayyubidene

I 1153 gjorde ghuzzerne (oghuziske tyrkere) opprør og tok Sanjar til fange. Han maktet å flykte etter tre år, men døde ett år senere. Atabegene, som zengidene og artukidene, var kun nominelt underlagt seldsjukkenes sultan, og hersket generelt sett Syria uavhengig av sultanen. Da Ahmed Sanjar døde i 1156 splittet det riket opp endelig, og gjorde atabegene i praksis selvstendige.

- Khorasan-seldsjukkene i Khorasan og Transoxania. Hovedstad: Merv

- Kerman-seldsjukkene

- Sultanatet Rum (eller Anatolia-seldsjukkene). Hovedstad: Iznik (Nikea), senere Konya (Iconium)

- Salghuridenes atabeghlik i Iran

- Eldiguzidenes atabeghlik i Irak og Aserbajdsjan. Hovedstad: Hamadan

- Buridenes atabeghlik i Syria. Hovedstad: Damaskus

- Zangis atabeghlik i Al Jazira (Nord-Mesopotamia). Hovedstad: Mosul

- Turkmenske beghliker: danishmendene, artukidene, saltukidene og mengujekidene i Lilleasia.

Etter det andre korstog ble Nur ad-Dins general Shirkuh, som hadde etablert seg i Egypt på fatimidiske landområder, etterfulgt av Saladin. Saladin gjorde etter hvert opprør mot Nur ad-Din, og, ved hans bortgang giftet Saladin seg med hans enke, erobret mesteparten av Syria, og etablerte ayyubide-dynastiet.

På andre fronter vokste Kongeriket Georgia å bli en regional makt, og utvidet sine grenser på storseldsjukks bekostning. Det samme gjaldt også gjenopplivingen av Det armenske kongeriket Kilikia under Leo II av Armenia i Anatolia. Abbasidekalifen An-Nasir begynte også å gjenhevde kalifens autoritet og allierte seg med den khoresmiske Takash.

I en kort periode var Togrul 3. sultan over hele seldsjukkriket utenom Anatolia. I 1194 derimot ble Togrul beseiret av Takash, Khoresm-rikets sjah, og Seldsjukkriket kollapset endelig. Av det tidligere seldsjukkriket gjenstod kun Rum-sultanatet i Anatolia. Mens dynastiet ble svekket på midten av 1200-tallet invaderte mongolene Anatolia i 1260-årene og delte det inn i mindre emirater kalt De anatoliske beyliker. Til slutt kom en av disse, den osmanske, til å vokse frem og erobre de resterende.

Ettermæle

Seldsjukkene ble utdannet i tjeneste av muslimske hoff som slaver eller leiesoldater. Dynastiet brakte vekkelse, energi og gjenforening til den islamske sivilisasjonen som til da hadde vært dominert av arabere og persere.

Seldsjukkene grunnla også universiteter og støttet også kunst og litteratur. Deres regjering karakteriseres av persiske astronomer som Omar Khayyám, og den persiske filosofen al-Ghazali. Under seldsjukkene ble nypersisk språket i historiske fortegnelser, mens den arabiske språkkulturens sentrum flyttet fra Bagdad til Kairo.[30]

Liste over Det store seldsjukkrikets sultaner

Utdypende artikkel: Liste over Seldsjukkrikets sultaner

| # | Laqab | Herskernavn | Regjering | Ekteskap | Etterfølgekrav |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din رکن الدنیا والدین |

Toghrul beg | 1037–1063 | 1) Altun Jan Khatun (2) Aka Khatun (3) Fulana Khatun (datter av Abu Kalijar) (4) Seyyidah Khatun (datter av Al-Qa'im, Abbaside-kalif) (5) Fulana Khatun (enke av Tsjaghri beg) |

sønn av Mikail (sønnesønn av Seldsjukk) |

| 2 | Diya ad-Dunya wa ad-Din Adud ad-Dawlah ضياء الدنيا و الدين عضد الدولة |

Alp Arslan | 1063–1072 | 1) Aka Khatun (enke av Toghrul 1.) (2) Safariyya Khatun (datter av Yusuf Qadir Khan, khagan av karakhanidene) (3) Fulana Khatun (datter av Smbat Lorhi) (4) Fulana Khatun (datter av Kurtchu bin Yunus bin Seljuk) |

sønn av Tsjaghri |

| 3 | Muizz ad-Dunya wa ad-Din Jalal ad-Dawlah معز الدین جلال الدولہ |

Malik-Shah 1. | 1072–1092 | 1) Turkan Khatun (datter av Ibrahim Tamghach Khan, khagan av Vestre Kara-Khanid) (2) Zubeida Khatun (datter av Yaquti ibn Tsjaghri) (3) Safariyya Khatun (datter av Isa Khan, sultan av Samarkand) (4) Fulana Khatun (datter av Romanos IV Diogenes) |

sønn av Alp Arslan |

| 4 | Nasir ad-Dunya wa ad-Din ناصر الدنیا والدین |

Mahmud 1. | 1092–1094 | sønn av Malik-Shah 1. | |

| 5 | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din رکن الدنیا والدین |

Barkiyaruq | 1094–1105 | sønn av Malik-Shah 1. | |

| 6 | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din Jalal ad-Dawlah رکن الدنیا والدین جلال الدولہ |

Malik-Shah 2. | 1105 | sønn av Barkiyaruq | |

| 7 | Ghiyath ad-Dunya wa ad-Din غیاث الدنیا والدین |

Tapar | 1105–1118 | 1) Nisandar Jihan Khatun (2) Gouhar Khatun (datter av Isma'il bin Yaquti) (3) Fulana Khatun (datter av Aksungur beg) |

sønn av Malik-Shah 1. |

| 8 | Mughith ad-Dunya wa ad-Din Jalal ad-Dawlah مُغيث الدنيا و الدين جلال الدولة |

Mahmud 2. | 1118–1131 | 1) Mah-i Mulk Khatun (d. 1130) (datter av Sanjar) (2) Amir Siti Khatun (datter av Sanjar) (3) Ata Khatun (datter av Ali bin Faramarz) |

son of Muhammad I |

| 9 | Muizz ad-Dunya wa ad-Din Adud ad-Dawlah مُعز الدنيا و الدين جلال الدولة |

Sanjar | 1118–1153 | 1) Turkan Khatun (datter av Muhammad Arslan Khan, khagan av Vestre Kara-Khanid) (2) Rusudan Khatun (datter av Demetrius 1. av Georgia) (3) Gouhar Khatun (datter av Isma'il bin Yaquti, enke av Tapar) (4) Fulana Khatun (datter av Arslan Khan, en kara-kitai-fange) |

sønn av Malik-Shah 1. |

| 10 | Ghiyath ad-Dunya wa ad-Din غیاث الدنیا والدین |

Dawud | 1131–1132 | Gouhar Khatun (datter av Masud) |

sønn av Mahmud 2. |

| 11 | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din رکن الدنیا والدین |

Toghril 2. | 1132–1135 | 1) Mumine Khatun (mor til Arslan-Shah) (2) Zubeida Khatun (datter av Barkiyaruq) |

sønn av Muhammad 1. |

| 12 | Ghiyath ad-Dunya wa ad-Din غیاث الدنیا والدین |

Masud | 1135–1152 | 1) Gouhar Nasab Khatun (datter av Sanjar) (2) Zubeida Khatun (datter av Barkiyaruq, enke av Toghril 2.) (3) Mustazhiriyya Khatun (datter av Qawurd) (4) Sufra Khatun (datter av Dubais) (5) Arab Khatun (datter av Al-Muqtafi) (6) Ummiha Khatun (datter av Amid ud-Deula bin Juhair) (7) Abkhaziyya Khatun (datter av David IV of Georgia) (8) Sultan Khatun (mor til Malik-Shah III) |

sønn av Muhammad 1. |

| 13 | Muin ad-Dunya wa ad-Din مُعين الدنيا و الدين |

Malik-Shah 3. | 1152–1153 | sønn av Mahmud 2. | |

| 14 | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din رکن الدنیا والدین |

Muhammad | 1153–1159 | 1) Mahd Rafi Khatun (datter av Kirman-Shah) (2) Gouhar Khatun (datter av Masud, enke av Dawud) (3) Kerman Khatun (datter av Al-Muqtafi) (4) Kirmaniyya Khatun (datter av Tughrul Shah, hersker over Kerman) |

sønn av Mahmud 2. |

| 15 | Ghiyath ad-Dunya wa ad-Din غیاث الدنیا والدین |

Suleiman-Shah | 1159–1160 | 1) Khwarazmi Khatun (datter av Muhammad Khwarazm Shah) (2) Abkhaziyya Khatun (datter av David 4. av Georgia, enke av Masud) |

sønn av Muhammad 2. |

| 16 | Muizz ad-Dunya wa ad-Din معز الدنیا والدین |

Arslan-Shah | 1160–1176 | 1) Kerman Khatun (datter av Al-Muqtafi, enke av Muhammad) (2) Sitti Fatima Khatun (datter av Ala ad-Daulah) (3) Kirmaniyya Khatun (datter av Tughrul Shah, hersker over Kerman, enke av Muhammad) (4) Fulana Khatun (søster av Izz al-Din Hasan Qipchaq) |

sønn av Toghril 2. |

| 17 | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din رکن الدنیا والدین |

Toghril 3. | 1176–1191<br />(første regjering) | Inanj Khatun (datter av Sunqur-Inanj, hersker over Rey, enke av Toghril 3.) |

søvv av Arslan-Shah |

| 18 | Muzaffar ad-Dunya wa ad-Din مظفر الدنیا والدین |

Qizil Arslan | 1191 | Inanj Khatun (datter av Sunqur-Inanj, hersker over Rey, enke av Muhammad ibn Ildeniz) |

sønn av Ildeniz (stebror av Arslan-Shah) |

| — | Rukn ad-Dunya wa ad-Din رکن الدنیا والدین |

Toghril III | 1192–1194 (andre regjering) |

sønn av Arslan-Shah |

Bildegalleri

-

Seljuq-era art: Ewer fra Herat i Afghanistan, datert 1180–1210 e.Kr. Messing utarbeidet i opptrykk med innlagt sølv og bitumen. British Museum.

-

Hodet til en mannlig kongeskikkelse, 1100- til 1200-tallet, funnet i Iran.

-

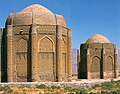

Kharāghān-tårnene, bygget i 1053 i Iran, er seldsjukkfyrstenes begravelsessted.

-

Seldsjukkesultanen Barkiyaruq

-

Seldsjukkesultanen Muhammad ibn Malik-Shah

Se også

- Artukidene

- Assassiner

- Atabeg

- Danishmendene

- Ghaznavideriket

- Rahat al-sudur

- Seldsjukke-arkitektur

- Seldsjukk-dynastiet

- Sultanatet Rûm

- Liste over tyrkiske dynastier og stater

Referanser

- ^ Rāvandī, Muḥammad (1385). Rāḥat al-ṣudūr va āyat al-surūr dar tārīkh-i āl-i saljūq. Tihrān: Intishārāt-i Asāṭīr. ISBN 9643313662.

- ^ a b Introduction to Islamic Civilisation. Cambridge University Press. 1976. s. 82. ISBN 0-521-20777-0.

- ^ Black, Edwin (2004). Banking on Baghdad: Inside Iraq's 7,000-year History of War, Profit and Conflict. John Wiley and Sons. s. 38. ISBN 0-471-67186-X.

- ^ a b c Bosworth, C. E.: «Turkish Expansion towards the west» i UNESCO History of Humanity, bind 4, titulert «From the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century». UNESCO Publishing/Routledge. Sitat side 391: «While the Arabic language retained its primacy in such spheres as law, theology and science, the culture of the Seljuk court and secular literature within the sultanate became largely Persianized; this is seen in the early adoption of Persian epic names by the Seljuk rulers (Qubād, Kay Khusraw and so on) and in the use of Persian as a literary language (Turkish must have been essentially a vehicle for everyday speech at this time).»

- ^ Stokes 2008, s. 615.

- ^ Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World, Ed. Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie, (Elsevier Ltd., 2009), 1110; sitat: «Oghuz Turkic is first represented by Old Anatolian Turkish which was a subordinate written medium until the end of the Seljuk rule.»

- ^ A New General Biographical Dictionary, Vol.2, Ed. Hugh James Rose, (London, 1853), 214.

- ^ Grousset, Rene: The Empire of the Steppes. New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press (1988). s. 167.

- ^ Grousset, Rene (1988). The Empire of the Steppes. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. s. 159 & 161. ISBN 0-8135-0627-1. «In 1194, Togrul III would succumb to the onslaught of the Khwarizmian Turks, who were destined at last to succeed the Seljuks to the empire of the Middle East.»

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (desember 2006). «East-West Orientation of Historical Empires». Journal of world-systems research. 12 (2): 223. Besøkt 13. september 2016.

- ^ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). «Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia». International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 496. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. Besøkt 13. september 2016.

- ^ Axner Ims, Gunvald. (2015, 29. desember). Seldsjukkriket I Anatolia. I Store norske leksikon. Hentet 26. november 2016 fra https://snl.no/Seldsjukkriket_i_Anatolia.

- ^ * «Aḥmad of Niǧde's al-Walad al-Shafīq and the Seljuk Past», A. C. S. Peacock, Anatolian Studies, Vol. 54, (2004), s. 97; Sitat: «With the growth of Seljuk power in Rum, a more highly developed Muslim cultural life, based on the Persianate culture of the Great Seljuk court, was able to take root in Anatolia.»

- Meisami, Julie Scott: Persian Historiography to the End of the Twelfth Century. Edinburgh University Press (1999), s. 143; «Nizam al-Mulk also attempted to organise the Saljuq administration according to the Persianate Ghaznavid model...»

- Encyclopaedia Iranica, «Šahrbānu», Online Edition: «... here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkmen heroes or Muslim saints ...»

- Josef W. Meri, Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, 2005, s. 399

- Michael Mandelbaum, Central Asia and the World, Council on Foreign Relations (mai 1994), s. 79

- Jonathan Dewald, Europe 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World, Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004, s. 24: «Turcoman armies coming from the East had driven the Byzantines out of much of Asia Minor and established the Persianized sultanate of the Seljuks.»

- Grousset, Rene: The Empire of the Steppes, Rutgers University Press (1991), s. 161 & 164; «renewed the Seljuk attempt to found a great Turko-Persian empire in eastern Iran." "It is to be noted that the Seljuks, those Turkomans who became sultans of Persia, did not Turkify Persia-no doubt because they did not wish to do so. On the contrary, it was they who voluntarily became Persians and who, in the manner of the great old Sassanid kings, strove to protect the Iranian populations from the plundering of Ghuzz bands and save Iranian culture from the Turkoman menace.»

- Shaw, Wendy M. K.: Possessors and possessed: museums, archaeology, and the visualization of history in the late Ottoman Empire; Utgitt av University of California Press (2003), ISBN 0520233352, ISBN 9780520233355; s. 5.

- ^ * Jackson, P. (2002). «Review: The History of the Seljuq Turkmens: The History of the Seljuq Turkmens». Journal of Islamic Studies. Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. 13 (1): 75–76. doi:10.1093/jis/13.1.75.

- Bosworth, C. E. (2001). Notes on Some Turkish Names in Abu 'l-Fadl Bayhaqi's Tarikh-i Mas'udi. Oriens, bind 36 (2001), s. 299–313.

- Dani, A. H., Masson, V. M. (Eds), Asimova, M. S. (Eds), Litvinsky, B. A. (Eds), Boaworth, C. E. (Eds). (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (Pvt. Ltd).

- Hancock, I. (2006). ON ROMANI ORIGINS AND IDENTITY. The Romani Archives and Documentation Center. The University of Texas at Austin.

- Asimov, M. S., Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). (1998). History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. IV: The Age of Achievement: AD 750 to the End of the Fifteenth Century, Part One: The Historical, Social and Economic Setting. Multiple History Series. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- Dani, A. H., Masson, V. M. (Eds), Asimova, M. S. (Eds), Litvinsky, B. A. (Eds), Boaworth, C. E. (Eds). (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers (Pvt. Ltd).

- ^ * Encyclopaedia Iranica, «Šahrbānu», Online Edition: «... here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkmen heroes or Muslim saints ...»

- Josef W. Meri, «Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia», Routledge, 2005, s. 399

- Michael Mandelbaum, «Central Asia and the World», Council on Foreign Relations (May 1994), s. 79

- Jonathan Dewald, «Europe 1450 to 1789: Encyclopedia of the Early Modern World», Charles Scribner's Sons, 2004, s. 24: «Turcoman armies coming from the East had driven the Byzantines out of much of Asia Minor and established the Persianized sultanate of the Seljuks.»

- ^ * C.E. Bosworth, «Turkmen Expansion towards the west» in UNESCO History of Humanity, Volume IV, titled «From the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century», UNESCO Publishing/Routledge, s. 391: «While the Arabic language retained its primacy in such spheres as law, theology and science, the culture of the Seljuk court and secular literature within the sultanate became largely Persianized; this is seen in the early adoption of Persian epic names by the Seljuk rulers (Qubād, Kay Khusraw and so on) and in the use of Persian as a literary language (Turkmen must have been essentially a vehicle for everyday speech at this time). The process of Persianization accelerated in the thirteenth century with the presence in Konya of two of the most distinguished refugees fleeing before the Mongols, Bahā' al-Dīn Walad and his son Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, whose Mathnawī, composed in Konya, constitutes one of the crowning glories of classical Persian literature.»

- Mehmed Fuad Köprülü, «Early Mystics in Turkish Literature», oversatt av Gary Leiser og Robert Dankoff, Routledge (2006) sitat s. 149: «If we wish to sketch, in broad outline, the civilization created by the Seljuks of Anatolia, we must recognize that the local—i.e., non-Muslim, element was fairly insignificant compared to the Turkish and Arab-Persian elements, and that the Persian element was paramount. The Seljuk rulers, to be sure, who were in contact with not only Muslim Persian civilization, but also with the Arab civilizations in al-jazlra and Syria—indeed, with all Muslim peoples as far as India—also had connections with [various] Byzantine courts. Some of these rulers, like the great 'Ala' al-Dln Kai-Qubad I himself, who married Byzantine princesses and thus strengthened relations with their neighbors to the west, lived for many years in Byzantium and became very familiar with the customs and ceremonial at the Byzantine court. Still, this close contact with the ancient Greco-Roman and Christian traditions only resulted in their adoption of a policy of tolerance toward art, aesthetic life, painting, music, independent thought—in short, toward those things that were frowned upon by the narrow and piously ascetic views [of their subjects]. The contact of the common people with the Greeks and Armenians had basically the same result. [Before coming to Anatolia,] the Turkmens had been in contact with many nations and had long shown their ability to synthesize the artistic elements that thev had adopted from these nations. When they settled in Anatolia, they encountered peoples with whom they had not yet been in contact and immediately established relations with them as well. Ala al-Din Kai-Qubad I established ties with the Genoese and, especially, the Venetians at the ports of Sinop and Antalya, which belonged to him, and granted them commercial and legal concessions. Meanwhile, the Mongol invasion, which caused a great number of scholars and artisans to flee from Turkmenistan, Iran, and Khwarazm and settle within the Empire of the Seljuks of Anatolia, resulted in a reinforcing of Persian influence on the Anatolian Turks. Indeed, despite all claims to the contrary, there is no question that Persian influence was paramount among the Seljuks of Anatolia. This is clearly revealed by the fact that the sultans who ascended the throne after Ghiyath al-Din Kai-Khusraw I assumed titles taken from ancient Persian mythology, like Kai-Khusraw, Kai-Ka us, and Kai-Qubad; and that. Ala' al-Din Kai-Qubad I had some passages from the Shahname inscribed on the walls of Konya and Sivas. When we take into consideration domestic life in the Konya courts and the sincerity of the favor and attachment of the rulers to Persian poets and Persian literature, then this fact [i.e., the importance of Persian influence] is undeniable. With- regard to the private lives of the rulers, their amusements, and palace ceremonial, the most definite influence was also that of Iran, mixed with the early Turkish traditions, and not that of Byzantium.»

- Stephen P. Blake, Shahjahanabad: The Sovereign City in Mughal India, 1639–1739. Cambridge University Press (1991). s. 123: «For the Seljuks and Il-Khanids in Iran it was the rulers rather than the conquered who were "Persianized and Islamicized»

- ^ * Encyclopaedia Iranica, «Šahrbānu», Online Edition: «... here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkmen heroes or Muslim saints ...»

- O. Özgündenli, «Persian Manuscripts in Ottoman and Modern Turkish Libraries Arkivert 22. januar 2012 hos Wayback Machine.», Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition

- Encyclopædia Britannica, «Seljuq», Online Edition: «... Because the Turkish Seljuqs had no Islamic tradition or strong literary heritage of their own, they adopted the cultural language of their Persian instructors in Islam. Literary Persian thus spread to the whole of Iran, and the Arabic language disappeared in that country except in works of religious scholarship ...»

- M. Ravandi, «The Seljuq court at Konya and the Persianisation of Anatolian Cities», i Mesogeios (Mediterranean Studies), vol. 25–26 (2005), s. 157–69

- F. Daftary, «Sectarian and National Movements in Iran, Khorasan, and Trasoxania during Umayyad and Early Abbasid Times», i History of Civilizations of Central Asia, bind 4, del 1; redigert av M. S. Asimov og C. E. Bosworth; UNESCO Publishing, Institute of Ismaili Studies: «... Not only did the inhabitants of Khurasan not succumb to the language of the nomadic invaders, but they imposed their own tongue on them. The region could even assimilate the Turkic Ghaznavids and Seljuks (eleventh and twelfth centuries), the Timurids (fourteenth–fifteenth centuries), and the Qajars (nineteenth–twentieth centuries) ...»

- ^ «The Turko-Persian tradition features Persian culture patronized by Turkic rulers.» Se Daniel Pipes: «The Event of Our Era: Former Soviet Muslim Republics Change the Middle East» in Michael Mandelbaum, «Central Asia and the World: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkemenistan and the World», Council on Foreign Relations, s. 79. Sitat: «In Short, the Turko-Persian tradition featured Persian culture patronized by Turcophone rulers.»

- ^ Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, Rutgers University Press, (1991), s. 574.

- ^ Bingham, Woodbridge, Hilary Conroy og Frank William Iklé, History of Asia, Vol. 1. Allyn & Bacon (1964), s. 98.

- ^

- An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples (Peter B. Golden. Otto Harrasowitz, 1992). s. 386:

- John Perry. «The Historical Role of Turkish in Relation to Persian of Iran». Iran & the Caucasus, Vol. 5, (2001), s. 193–200: «We should distinguish two complementary ways in which the advent of the Turks affected the language map of Iran. First, since the Turkish-speaking rulers of most Iranian polities from the Ghaznavids and Seljuks onward were already Iranized and patronized Persian literature in their domains, the expansion of Turk-ruled empires served to expand the territorial domain of written Persian into the conquered areas, notably Anatolia and Central and South Asia. Secondly, the influx of massive Turkish-speaking populations (culminating with the rank and file of the Mongol armies) and their settlement in large areas of Iran (particularly in Azerbaijan and the northwest), progressively turkicized local speakers of Persian, Kurdish and other Iranian languages»

- Ifølge C.E. Bosworth: «The eastern Caucasus came under Saljuq control in the middle years of the 5th/11th century, and in ca. 468/1075-56 Sultan Alp Arslān sent his slave commander ʿEmād-al-dīn Savtigin as governor of Azerbaijan and Arrān, displacing the last Shaddadids. From this period begins the increasing Turkicization of Arrān, under the Saljuqs and then under the line of Eldigüzid or Ildeñizid Atabegs, who had to defend eastern Transcaucasia against the attacks of the resurgent Georgian kings. The influx of Oghuz and other Türkmens was accentuated by the Mongol invasions. Bardaʿa had never revived fully after the Rūs sacking, and is little mentioned in the sources.» (C. E. Bosworth, «Arran» i Encyclopedia Iranica)

- Ifølge Fridrik Thordarson: «Iranian influence on Caucasian languages. There is general agreement that Iranian languages predominated in Azerbaijan from the 1st millennium b.c. until the advent of the Turks in a.d. the 11th century (see Menges, pp. 41–42; Camb. Hist. Iran IV, pp. 226–28, and VI, pp. 950–52). The process of Turkicization was essentially complete by the beginning of the 16th century, and today Iranian languages are spoken in only a few scattered settlements in the area.»

- ^ Wink, Andre, Al Hind the Making of the Indo Islamic World, Brill Academic Publishers, Jan 1, 1996, ISBN 90-04-09249-8 s. 9

- ^ Andre Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, Vol.2, (Brill, 2002), 9. (Abonnement påkrevet)

- ^ Iran, The Columbia World Dictionary of Islamism, ed. Antoine Sfeir and John King, transl. John King, (Columbia University Press, 2007), s. 141.

- ^ «Dhu'l Qa'da 463/ August 1071 The Battle of Malazkirt (Manzikert)». Besøkt 8. september 2007.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, «Nizam al-Mulk», Online Edition

- ^ "The Kings of the East and the West": The Seljuk Dynastic Concept and Titles in the Muslim and Christian sources, Dimitri Korobeinikov, The Seljuks of Anatolia, ed. A.C.S. Peacock and Sara Nur Yildiz, (I.B. Tauris, 2015), 71.

- ^ a b c d Wink, Andre: Al Hind the Making of the Indo Islamic World. Brill Academic Publishers (1. januar 1996), ISBN 90-04-09249-8. s. 9–10

- ^ Biran, Michel, The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History, (Cambridge University Press, 2005), s. 44.

- ^ Andre Wink, Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, Vol.2, 16. (Abonnement påkrevet)

Litteratur

- Previté-Orton, C. W. (1971). The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tetley, G. E. (2008). The Ghaznavid and Seljuk Turks: Poetry as a Source for Iranian History. Abingdon. ISBN 9780415431194.

- Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. New York: Facts On File. 2008. ISBN 9780816071586. Arkivert fra originalen 14. februar 2017.