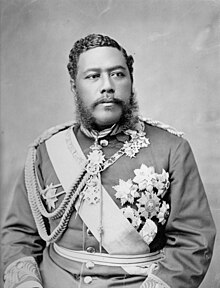

Kalākaua

| Kalākaua | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HM The King | |||||

Kalākaua I | |||||

| Reign | February 12, 1874 — January 30, 1891 (16 years, 342 days) | ||||

| Predecessor | Lunalilo | ||||

| Successor | Liliuokalani | ||||

| Born | November 16, 1836 Honolulu, Oahu | ||||

| Died | January 20, 1891 (aged 54) Palace Hotel, San Francisco | ||||

| Burial | Mauna Ala Royal Mausoleum | ||||

| Spouse | Queen Kapiolani | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Kalākaua | ||||

| Father | High Chief Caesar Kaluaiku Kapaʻakea | ||||

| Mother | High Chiefess Analea Keohokālole | ||||

Kalākaua I (November 16, 1836 - January 20, 1891) was the last king of Hawaii. His full name was David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Mahinulani Nalaiaehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua.[1] He was sometimes called The Merrie Monarch. He was king from February 12, 1874 until his death on January 20, 1891.

Early life

Kalākaua's parents were a high chief and a high chiefess. He had two older siblings and six younger siblings.[1] When he was four, he started school. He became fluent in English and the Hawaiian language. He started studying law at age 16. However, his government positions kept him from completing his legal training. By 1856, Kalākaua was a major on the staff of King Kamehameha IV. He had also led a political organization known as the Young Hawaiians. Kalākaua also served in the Department of the Interior. In 1863, he was appointed postmaster general.

Reign as King

The king before Kalākaua was King Lunalilo. He died on February 3, 1874. Kalākaua was elected to replace him. Kalākaua named his brother, William Pitt Leleiohoku, as his heir.

Kalākaua started his reign with a tour of the Hawaiian islands. This made him more popular. In October 1874, he sent representatives to the United States to negotiate a treaty. In November, Kalākaua went to Washington DC to meet Ulysses S. Grant. An agreement was reached and the treaty was signed on January 30, 1875. The treaty allowed certain Hawaiian goods, mainly sugar and rice, to come into the United States tax-free.

During the early part of Kalākaua's reign, he dismissed many cabinets and appointed new ones. This drew criticism from people who wanted Hawaiian government to be like the United Kingdom's constitutional monarchy. They believed the legislature should control the cabinet ministers rather than the king. This struggle continued throughout Kalākaua's reign.

In 1881, King Kalākaua left Hawaii on a trip around the world. He went to study immigration and to improve foreign relations. He also wanted to study how other rulers ruled. In his absence, his sister and heir, Princess Liliʻuokalani, ruled as regent. (Prince Leleiohoku, the former heir, had died in 1877.) The King received a royal welcome in San Francisco. In the Empire of Japan, he met with the Meiji Emperor. He continued through Qing Dynasty China, Siam under King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), Burma, British Raj India, Egypt, Italy, Belgium, the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the French Third Republic, Spain, Portugal, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and back through the United States. During this trip, he met with many other heads of state, including Pope Leo XIII, Umberto I of Italy, Tewfik, Viceroy of Egypt, William II of Germany, Rama V of Siam, President Chester Arthur, and Victoria of the United Kingdom. In this, he became the first king to travel around the world.[2]

Kalākaua also built ʻIolani Palace. It cost $300,000, an amount unheard of at the time. Many of the furnishings in the palace were ordered by Kalākaua while he was in Europe.

Kalākaua decided to build the Kamehameha Statue. It honored Kamehameha I, the first king of the whole Hawaiian Islands. The original statue was lost when the ship carrying it sank near the Falkland Islands. A replacement was ordered and unveiled by the king in 1883. The original statue was later repaired and sent to Hawaii in 1912. A third statue, erected in 1969, is in the United States Capitol. It is the only statue there that commemorates a native Hawaiian.

King Kalākaua is said to have wanted to build a Polynesian Empire. In 1886, the legislature gave the government $30,000 for the formation of a Polynesian confederation. The King sent representatives to Sāmoa. There Malietoa Laupepa agreed to a confederation between the two kingdoms. This confederation did not last very long, because King Kalākaua lost power the next year to the Bayonet Constitution.

By 1887, some people were very frustrated with Kalākaua. They blamed him for the Kingdom's growing debt. They accused him of being a spendthrift. Some foreigners wanted to force him to abdicate and put his sister Liliʻuokalani onto the throne. Others wanted to end the monarchy altogether and make the islands part of the United States. The people who wanted to be part of the United States formed a group called the Hawaiian League. In 1887, members of the League armed with guns got together. The King was frightened by this show of force. He offered to transfer his powers to the foreign ministers representing the United States, the United Kingdom, or Portugal. The members of the league instead asked him to sign a new constitution.

This new constitution was nicknamed the Bayonet Constitution. It took away much of the King's executive power. It took away the voting rights of most native Hawaiians. The legislature could override a veto by the King. The King was no longer allowed to take action without approval of the cabinet. The House of Nobles, the house of legislature appointed by the King, was to be elected. Non-Hawaiian citizens could now vote. Robert Wilcox led a counter-revolution to give power back to the king, but it failed.

By 1890, the King was ill. Under the advice of his physician, he went to San Francisco. His health continued to get worse. He died on January 20, 1891 at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco. His final words were, "Tell my people I tried."

Kalākaua's remains were sent to Honolulu aboard the American cruiser USS Charleston. Because he did not have any children, his sister, Liliʻuokalani, became queen.

Legacy

King Kalākaua was called "the Merrie Monarch" because he loved the joyful things in life. While he was king, people started to do hula again. (It had been banned by Queen Kaʻahumanu in 1830.) There is a hula festival named for him, the Merrie Monarch Festival. He also brought back the Hawaiian martial art of Lua, and surfing. He and his brother and sisters were known as the "Royal Fours" for their musical talents. He wrote "Hawaii Ponoi", which is the state song of Hawaii today. Kalākaua strongly supported the ukulele as a Hawaiian instrument.

"Kalākaua Avenue" in Waikiki is named after him. It is the main avenue of Waikiki. It goes from the Ala Wai Canal to Waikiki beach. It continues almost to the Diamond Head crater.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Christopher Buyers. "Kauai Genealogy". Royal Ark web site. Retrieved 2010-02-28.

- ↑ "Ka Momi". Archived from the original on 2010-06-20. Retrieved 2013-10-02.

Further reading

- Tabrah, Ruth M. (1984). Hawaii: A History. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393302202.

Other websites

- Ukulele Hall Of Fame Museum - David Kalākaua Archived 2017-12-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Kalākaua elected king

- David Kalākaua

- Kalākaua at Find a Grave

| Preceded by Lunalilo |

King of Hawaii 1874 - 1891 |

Succeeded by Liliʻuokalani |