ภคัต สิงห์

ภคัต สิงห์ | |

|---|---|

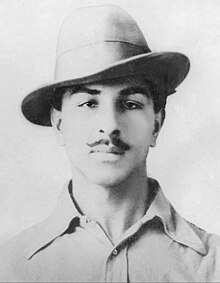

สิงห์เมื่อปี 1929 | |

| เกิด | 27 กันยายน ค.ศ. 1907[a] บังกา บริติชอินเดีย (ปัจจุบันอยู่ในประเทศปากีสถาน) |

| เสียชีวิต | 23 มีนาคม ค.ศ. 1931 (23 ปี) เรือนจำกลางลาฮอร์ ลาฮอร์ บริติชอินเดีย (ปัจจุบันอยู่ในประเทศปากีสถาน) |

| สาเหตุเสียชีวิต | ประการชีวิตด้วยการแขวนคอ |

| อนุสรณ์สถาน | อนุสรณ์ผู้พลีตนเพื่อชาติฮุสเซนีวาลา |

| ชื่ออื่น | ชาฮีเดอาซาม (Shaheed-e-Azam) |

| องค์การ | เนาชวันภารตสภา สมาคมสาธารณรัฐสังคมนิยมฮินดูสถาน |

| ผลงานเด่น | Why I Am an Atheist |

| ขบวนการ | เอกราชอินเดีย |

| ถูกกล่าวหา | ฆาตกรรมจอห์น พี. ซอนเดอส์ (John P. Saunders) และจันนัน สิงห์ (Channan Singh)[5] |

| รับโทษ | ประหารชีวิต |

| สถานะทางคดี | ประหารชีวิต |

ภคัต สิงห์ (อักษรโรมัน: Bhagat Singh, 27 กันยายน 1907[a] – 23 มีนาคม 1931) เป็นนักปฏิวัติชาวอินเดีย[6] ผู้มีส่วนร่วมในการฆาตกรรมตำรวจชาวอังกฤษชั้นผู้น้อยซึ่งผิดจากเป้าหมายจริง[7] ซึ่งตั้งใจจะเป็นการแก้แค้นการเสียชีวิตของนักชาตินิยมอินเดียคนหนึ่ง[8] เขามีส่วนร่วมในการวางระเบิดสภานิติบัญญัติกลางในเดลีที่เป็นการทำไปในเชิงสัญลักษณ์ และทำการอดอาหารประท้วงในเรือนจำ เรื่องราวการอดอาหารประท้วงในเรือนจำของเขาแพร่หลายผ่านหนังสือพิมพ์ทำให้เขากลายเป็นคนมีชื่อเสียงโดยเฉพาะในภูมิภาคปัญจาบ เขาถูกประหารชีวิตเมื่อวัย 23 และนับจากนั้นกลายมาเป็นผู้พลีชีพเพื่อชาติและวีรบุรุษท้องถิ่นของอินเดียเหนือ[9] เขาได้รับอิทธิพลทางการเมืองหลัก ๆ จากลัทธิบอลเชวิก และ ลัทธิอนาธิปไตย[10][11][12][13][14] เขามีส่วนร่วมในการสนับสนุนกองทัพในอินเดียในทศวรรษ 1930 และกระตุ้นให้ทั้งภายในพรรคคองเกรสแห่งชาติและกลุ่มเคลื่ออนไหวเรียกร้องเอกราชอินเดียได้ใคร่ครวญตัวเองใหม่ในแนวทางอหิงสาของตน[15]

ในเดือนธันวาคม 1928 ภคัต สิงห์ และมิตรสหาย ศิวราม ราชคุรุ ซึ่งล้วนเป็นสมาชิกของสมาคมสาธารณรัฐสังคมนิยมฮินดูสถาน (หรือ HSRA) ก่อการฆาตกรรมจอห์น ซอนเดอส์ (John Saunders) เจ้าหน้าที่ตำรวจชาวอังกฤษวัย 21 ปีในลาฮอร์ จังหวัดปัญจาบ ทั้งคู่ฆาตกรรมผิดคน เป้าหมายจริงของทั้งคู่คือผู้บัญชาการตำรวจอาวุโส เจมส์ สก็อต (James Scott)[16] ซึ่งทั้งคู่เชื่อว่าเป็นผู้รับผิดชอบการเสียชีวิตของลาลา ลาชปาต ราย ผู้นำชาตินิยมอินเดียที่เป็นที่ได้รับความนิยม หลังสก็อตสั่งให้รายถูกทุบตีด้วยตะบองลาตี รายเสียชีวิตในสองสัปดาห์ต่อมาด้วยหัวใจวาย ซอนเดอส์ถูกยิงขณะขี่จักรยานยนต์ออกจากสถานีตำรวจ เขาถูกยิงล้มลงด้วยกระสุนนัดเดียวจากราชคุรุซึ่งเป็นนักแม่นปืน ยิงจากฝั่งตรงข้ามถนน[17][18] ขณะที่ล้มลงบาดเจ็บนั้น สิงห์ยิงเข้าที่ซอนเดอส์ในระยะใกล้หลายครั้งจนเสียชีวิต รายงานนิติเวชระบุว่าซอนเดอส์ถูกกระสุนรวมแปดนัด[19] มิตรสหายอีกคนของสิงห์ จันทระ ศิขร อาฌาด ใช้ปืนยิงสังหารหัวหน้าตำรวจชาวอินเดีย จันนัน สิงห์ (Channan Singh) ซึ่งพยายามไล่จับสิงห์และราชคุรุขณะหลบหนี[17][18]

หลังหลบหนีสำเร็จ ภคัต สิงห์ และมิตรสหายใช้ชื่อปลอมเพื่อประกาศตัวล้างแค้นการเสียชีวิตของลาชปาต ราย ติดป้ายประกาศที่แก้ไขให้ระบุว่าจอห์น ซอนเดอส์ เป็นเป้าหมายการสังหารแทนที่เจมส์ สก็อต[17] สิงห์หลบหนีเป็นเวลาหลายเดือน ก่อนจะกลับมาอีกครั้งในเดือนเมษายน 1929 เขาและมิตรสหาย บาตูเกศวร ทัตต์ วางระเบิดทำมือความรุนแรงต่ำสองชิ้นบนม้านั่งว่างในสภานิติบัญญัติกลางในย่านเมืองเก่าเดลี ทั้งคู่โปรยใบปลิวลงจากแกลเลอรีลงบนสมาชิกสภานิติบัญญัติซึ่งนั่งอยู่ด้านล่าง ตะโกนคำขวัญ และยินยอมให้ถูกเข้าหน้าที่จับกุม[20] หลังถูกจับกุมและด้วยผลจากเหตุการณ์ในสภานิติบัญญัตินี้ทำให้ทราบว่าสิงห์เป็นผู้ก่อเหตุสังหารซอนเดอส์ ขณะรอศาลตัดสิน สิงห์ได้รับความเห็นอกเห็นใจจากสาธารณะหลังเขากระทำการอดอาหารประท้วงตามชติน ทาสในเรือนจำเพื่อเรียกร้ งสภาพความเป็นอยู่ที่ดีขึ้นให้กับนักโทษชาวอินเดีย ทาสเสียชีวิตจากการขาดอาหารในเดือนกันยายน 1929

ภคัต สิงห์ ถูกตัดสินมีความผิดฐานฆาตกรรมจอห์น ซอนเดอส์ และจันนัน สิงห๋ เขาถูกประหารชีวิตในเดือนมีนาคม 1931 อายุได้ 23 ปี เขากลายมาเป็นวีรบุรุษท้องถิ่นหลังเสียชีวิต ชวาหรลาล เนหรู เคยเขียนเกี่ยวกับเขาว่า: "ภคัต สิงห์ ไม่ได้กบายมาเป็นที่นิยมเพราะการก่อการร้ายของเขา แต่เป็นเพราะเขาดูเหมือนจะได้แก้แค้นให้กับเกียรติยศของลาลา ลาชปาต ราย ในขั่วขณะ และเป็นการแก้แค้นให้กับชาติ ผ่านทางเขา [ราย] สิงห์กลายมาเป็นสัญลักษณ์; การลงมือของเขาถูกลืม [แต่]ลักษลักษณ์นี้จะดำรงอยู่ และภายในไม่กี่เดือน เมืองแต่ละเมือง หมู่บ้านแต่บะแห่งในปัญจาบ และในอินเดียเหนือส่วนอื่น ๆ จะก้องกังวาลไปด้วยชื่อของเขา"[21] สิงห์ในฐานะเอธิสต์และนักสังคมนิยม ได้รับการเชิดชูในอินเดียจากกลุ่มต่าง ๆ ทางการเมือง ตั้งแต่คอมมิวนิสต์ซ้ายจัด ไปจนถึงชาตินิยมฮินดูขวาจัด บางครั้งสิงห์ได้รับการเรียกขานเป็น ชาฮีเด-อาฌาม (Shaheed-e-Azam; "ผู้พลีชีพผู้ยิ่งใหญ่") ในภาษาอูรดูและภาษาปัญจาบ[22]

อ้างอิง

- ↑

- Deol, Jeevan Singh (2004). "Singh, Bhagat [known as Bhagat Singh Sandhu". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/73519.

Singh, Bhagat (1907–1931), revolutionary and writer, was born in the village of Banga, Punjab, India (now in Pakistan) on 27 September 1907, the second of the four sons and three daughters of Kishan Singh Sandhu, a farmer and political activist, and his wife, Vidyavati.

(ต้องรับบริการหรือเป็นสมาชิกหอสมุดสาธารณะสหราชอาณาจักร) - "Bhagat Singh", Encyclopedia Britannica, 2021,

Bhagat Singh, (born September 27, 1907, Lyallpur, western Punjab, India [now in Pakistan]—died March 23, 1931, Lahore [now in Pakistan]) (subscription needed)

- Phanjoubam, Pradip (2016), The Northeast Question: Conflicts and Frontiers, Oxford and New York: Routledge, pp. 68–69, ISBN 978-1-138-95798-5,

Consider this. 27 September is the birthday of Google. This day is also the birthday of well-known and respected Indian freedom fighter Bhagat Singh, though some claim 28 September to be his birthday. For all the years after Indian independence, Bhagat Singh's birthday was what the Indian media remembered on 27 September, with the union government's Directorate of Advertising and Visual Publicity (DAVP) issuing large eulogising display advertisements ahead of the day, reminding the nation of the day's significance in the Indian independence movement and nation-building. But by the turn of the twenty-first century, amidst the excitement of changes brought about by the liberalisation of the Indian economy and its consequent growing integration with the global market, all major Indian news channels and newspapers began enthusiastically remembering Google, carrying features on this phenomenon of the digital age for days, and in the process, virtually marginalised the memory of Bhagat Singh to the periphery of the media's, and therefore, the public's consciousness.2 Obviously, the paradigms of history writing are yet getting set for another revolution. If history is the story of the state, as Carr suggested, then history telling must also have to change with the transformation the nature of modern States is going through.

- Noorani, A. G. (2001), The Trial of Bhagat Singh: Politics of Justice, Oxford University Press, p. 9, ISBN 978-0-19-579667-4,

Bhagat Singh was born in the village Banga in Lyallpur, on September 27, 1907, in a family of revolutionaries and in a clime in which the spirit of revolt gripped a large number of people in the Punjab.

- Dayal, Ravi, บ.ก. (1995), We Fought Together for Freedom: Chapters from the Indian National Movement, Delhi: Oxford University Press, p. 139, ISBN 978-0-19-563286-6,

Bhagat Singh was born on 27 September 1907 in the village of Banga in the Lyallpur district of Punjab (now in Pakistan) into a patriotic family.

- Singh, Fauja (1972), Eminent Freedom Fighters of Punjab, Punjab University, Department of Punjab Historical Studies, p. 80, OCLC 504464385,

Bhagat Singh He belongs to the front rank of Punjabi heroes martyred in the cause of national movement . ... He was born on September 27 , 1907.

- Aggarwal, Som Nath (1995), The heroes of Cellular Jail: Study based on personal memoirs of Indian freedom fighters incarcerated in the Cellular Jail, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, in connection with freedom movement, 1857-1945; includes a list of prisoners period-wise and state-wise, Patiala: Publication Bureau, Punjab University, p. 193, ISBN 9788173801075, OCLC 33970606,

In the Punjab , Lahore was once again agog with revolutionary activities and Bhagat Singh who was to become Shaheed - i - Azam in subsequent years was on the forefront . He was born on 27 September 1907 and belonged to village Khatkar

- Communist Party of India (Marxist) History Commission (2005), History of the Communist Movement in India: The Formative Years, 1920–1933, New Delhi: CPI (M) Publications and LeftWord Books, p. 231, ISBN 9788187496496, OCLC 493429162,

Bhagat Singh 1907-1931 One of the most outstanding revolutionaries of India , martyred at the age of 23. Born in a peasant family in Banga village of Lyallpur district of Punjab on September 27 , 1907

- Mittal, Satish Chandra; National Council for Educational Research and Training(India) (2004), Modern India: a textbook for Class XII, Textbooks from India, vol. 18, New Delhi: National Council for Educational Research and Training, p. 219, ISBN 9788174501295, OCLC 838284530,

Sardar Bhagat Singh was the symbol of young revolutionaries . He was born in a place called Banga in the Layalpur district on 27 September 1907.

- Singh, Bhagat; Gupta, D. N. (2007), Gupta, D. N.; Chandra, Bipan (บ.ก.), Selected Writings, New Delhi: National Book Trust, p. xi, ISBN 9788123749419, OCLC 607855643,

Bhagat Singh was born in a patriotic family on 27 September 1907 in the village Khatkar Kalan , tehsil Banga , district Jalandhar , though his father , Sardar Kishan Singh , had shifted to Layallpur ( now Faisabad in Pakistan )

- Deol, Jeevan Singh (2004). "Singh, Bhagat [known as Bhagat Singh Sandhu". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/73519.

- ↑ Sohi, Seema (2014), Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance, and Indian Anticolonialism in North America, Oxford University Press, p. 195, ISBN 978-0-19-939044-1,

... and on March 23, 1931, twenty-three year old Bhagat Singh was hanged. Born on September 28, 1907, Bhagat Singh came from a family of freedom fighters

- ↑ Parashar, Swati (2018), "Terrorism and the Postcolonial 'State'", ใน Rutazibwa, Olivia U.; Shilliam, Robbie (บ.ก.), Routledge Handbook of Postcolonial Politics, Routledge, p. 178, ISBN 978-1-317-36939-4,

Footnote 2: Bhagat Singh (28 September 1907 – 23 March 1931) was an Indian freedom fighter with socialist revolutionary leanings.

- ↑ Sanyal et al. (2006), pp. 19, 26

- ↑ Deol, Jeevan Singh (2004). "Singh, Bhagat [known as Bhagat Singh Sandhu". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/73519.

The trial of Bhagat Singh and a number of his associates from the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association for the killing of Saunders and Channan Singh followed. On 7 October 1929 Bhagat Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev Thapar were sentenced to death.Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar, and Shiv Ram Hari Rajguru were executed by hanging at the central gaol, Lahore, on 23 March 1931.

(ต้องรับบริการหรือเป็นสมาชิกหอสมุดสาธารณะสหราชอาณาจักร) - ↑

- Raza, Ali (2020), Revolutionary Pasts: Communist Internationalism in Colonial India, Cambridge University Press, pp. 106–107, ISBN 978-1-108-48184-7,

Bhagat Singh's life epitomized the political journeys of many disaffected youths who took to revolutionary and militant activism. Involved in a (mistaken) high-profile assassination of John Saunders, ...

- Moffat, Chris (2019), India's Revolutionary Inheritance: Politics and the Promise of Bhagat Singh, Cambridge University Press, pp. 78–79, ISBN 978-1-108-75005-9,

One month after Lajpat Rai's death, at 4:30 pm on 17 December 1928, members of the HSRA ambushed Assistant Superintendent of Police J. P. Saunders as he was leaving the police station on Lahore's College Road. He was shot once by Shivaram Rajguru, and then again by Bhagat Singh." As the two fled through the gates of the DAV College located opposite the station, their comrade Chandrashekhar Azad fired at the pursuing officer, Constable Chanan Singh. Both Singh and Saunders died from their wounds. Amid the chaos, there was some room for farce. Saunders was not the primary target; the HSRA's Jaigopal mistook the assistant for his boss, Mr. Scott, the man who had ordered police to charge the Simon Commission protestors two months earlier. Once it was clear this was a subordinate and not Scott, the revolutionaries scrambled to amend posters prepared in advance to announce the act.

- Raza, Ali (2020), Revolutionary Pasts: Communist Internationalism in Colonial India, Cambridge University Press, pp. 106–107, ISBN 978-1-108-48184-7,

- ↑

- Vaidik, Aparna (2021), Waiting for Swaraj: Inner Lives of Indian Revolutionaires, Cambridge University Press, p. 121, ISBN 978-1-00-903238-4,

The memoirs poignantly recount how they would be filled with agony and remorse after the assassinations and the deaths of the innocent. For instance, Azad shot the Indian constable Chanan Singh, who had chased Bhagat and Rajguru as they escaped through the DAV College after shooting Saunders. Azad was standing guard a few metres away from Bhagat and Rajguru supervising the operation and, if needed, was supposed to give them cover. Azad called out to Chanan Singh to give up the chase before shooting but Chanan did not heed the warning and kept running. Azad lowered his gun and aimed at his legs and shot a preventive bullet. It got Chanan in the groin and he eventually bled to death. The well-being of Chanan Singh's family kept nagging Azad, who would voice his worries time and again to his associates.

- Vaidik, Aparna (2021), Waiting for Swaraj: Inner Lives of Indian Revolutionaires, Cambridge University Press, pp. 121–122, ISBN 978-1-00-903238-4,

Despite it being a vengeful act, even Rajguru and Bhagat Singh were deeply disturbed and filled with remorse after shooting Saunders. Rajguru opined: "Bhai bada sundar naujawan tha [Saunders!]. Uske gharwalon ko kaisa lag raha hoga?' (Brother, he [Saunders] was a very handsome young man. How his family must be feeling?)! Similar was Bhagat's state. Mahour recounts that he met Bhagat after the Saunders murder and found him deeply shaken. 'Kitna udvelit tha unka manas. Unke sayant kanth se unka uddveg ubhara pada tha. Baat karte karte ruk jaate the aur der tak chup raha kar phir baat ka sutra pakad kar muskaraane ke prayatn karte aage badte the' (How shaken his mind was. Despite his measured tone his discomposure was visible. He would suddenly stop talking mid-sentence and then stay quiet for a while before making an effort to smile and move forward.)

- Vaidik, Aparna (2021), Waiting for Swaraj: Inner Lives of Indian Revolutionaires, Cambridge University Press, p. 121, ISBN 978-1-00-903238-4,

- ↑ *Maclean, Kama (2016), "The Art of Panicking Quietly: British Expatriate Responses", ใน Fischer-Tine, Harald (บ.ก.), Anxieties, Fear and Panic in Colonial Settings: Empires on the verge of a Nervous Breakdown, Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 154, ISBN 978-3-319-45136-7,

Several HSRA members, including Bhagat Singh and Sukhdev, had dabbled in journalism and enjoyed friendships with journalists and editors in nationalist newspapers in Punjab, UP and Delhi, with the result that much of the coverage in Indian-owned newspapers was sympathetic to the revolutionary cause. By the end of 1929, Bhagat Singh was a household name, his distinctive portrait widely disseminated ...

- Grant, Kevin (2019), Last Weapons: Hunger Strikes and Fasts in the British Empire, 1890–1948, University of California Press, p. 143, ISBN 978-0-520-97215-5,

After 1929 the British regime became increasingly concerned that the hunger strike might break down discipline across the prison system and demoralize the police and army. In this year the power of the hunger strike was demonstrated by members of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association before and during their trial in the second Lahore conspiracy case. This case was widely publicized because several of the defendants had been involved either in the assassination of a police official and a head constable or in the bombing of the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi. Bhagat Singh, the charismatic leader of the group, had participated in both actions.

- Raza, Ali (2020), Revolutionary Pasts: Communist Internationalism in Colonial India, Cambridge University Press, p. 107, ISBN 978-1-108-48184-7,

His trial became the stuff of popular legend, as did his hanging — and those of his comrades Raj Guru and Sukhdev – in Lahore in March 1931. Bhagat Singh's death earned him the title of Shaheed-e-Azam (Great Martyr). He was not the only Shaheed who went to the gallows for his or her revolutionary activities, nor was he the only Shaheed-e-Azam.

- Grant, Kevin (2019), Last Weapons: Hunger Strikes and Fasts in the British Empire, 1890–1948, University of California Press, p. 143, ISBN 978-0-520-97215-5,

- ↑ Loadenthal, Michael (2017), The politics of attack: Communiques and insurrectionary violence, Digital Edition, Contemporary Anarchist Studies, Manchester University Press, p. 74, ISBN 978-1-5261-1445-7,

Though numerous illegalist anarchists are (in)famous due to their linkages to specific acts of political violence, the tradition includes many lesser known individuals. These include French illegalists Clément Duval, Francois Claudius Koenigstein (aka Ravachol), ..; and Indian socialist-anarchist Bhagat Singh who played a major role in India's anti-colonial struggle.

- ↑ Jeffrey, Craig (2010), Timepass: Youth, Class, and the Politics of Waiting in India, Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, p. 111, ISBN 978-0-8047-7073-6,

Bhagat Singh (1907–34), often referred to as "Shaheed (martyr) Bhagat Singh" was a freedom fighter influenced by communism and anarchism who became involved as a teenager in a number of revolutionary anti-British organizations. He was hanged for shooting a police officer in response to the killing of a veteran freedom fighter.

- ↑ Balinisteanu, Tudor (2013), Violence, Narrative and Myth in Joyce and Yeats: Subjective Identity and Anarcho-Syndicalist Traditions, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 141, ISBN 978-0-230-29095-2,

To capture better the political value of the manifestation of the contrary tendencies of monoglossia and heteroglossia in Joyce and Sorel, we might employ a term used to define the identity of the Indian anarchist Bhagat Singh: 'mystical atheism'. Singh developed his own brand of anarchism in the context of anti-colonial movements in India led by Gandhi and partly in relation to Irish anti-imperialism. Singh read anarchist philosophy extensively and translated Daniel Breen's My Fight for Irish Freedom (1924) under the name of Balwant Singh (Dublin, 1982, p. 54). In his 'Why I am an Atheist's, written in jail awaiting execution, Singh reflected on the role of religious belief in producing the romantic conviction required of the revolutionaries, but reasserted his faith in reason.

- ↑ Moffat, Chris (2019), India's Revolutionary Inheritance: Politics and the Promise of Bhagat Singh, Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/9781108655194, ISBN 978-1-108-49690-2, S2CID 158993652,

(p. 34) The worldliness of these spaces and print areas – rallies against the bombing of Medina at Mochi Bagh, reports from Munich in Lajpat Rai's weekly. The People, speeches on South Africa at the Bradlaugh Hall, books on the Soviet Union smuggled into Lahore by underground booksellers – allows us to approach a problem related to Bhagat Singh's biography: the manner in which the young man negotiated transnational currents so deftly, citing French anarchists in manifestos and regularly alluding to revolutionary Moscow, without ever once leaving India. (p. 151) The second function of the journey metaphor is to posit the eventual arrival at something refined, comprehensive, stable. If Bhagat Singh is separated from a 'terrorist' past above, here he is propelled into the future, beyond the event of death. The nature of his destination varies across the corps: for some it is most certainly Marxist, for others anarchist. <Footnote 128:Regarding the move from 'libertarian socialism' to 'decentralized collectives', the American historian and anarchist activist Maia Ramnath writes on Bhagat Singh that 'one revolutionary who might have been capable of persuasively elaborating such a synthesis died too soon to do so.' Ramnath, Decolonizing Anarchism, 145>

- ↑ Vaidik, Aparna (2021), Waiting for Swaraj: Inner Lives of Indian Revolutionaries, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, p. 123, ISBN 978-1-108-83808-5, LCCN 2021005366,

As Bhagat wrote in one his essays: 'All forms of government rest on violence.' The state, in the Marxist–anarchist conception, was the focal point of violence. "at is, the state created and perpetuated conditions of violence. If elimination of structural violence was the aim then the state as a form of human governance had to be done away with. Bhagat Singh questioned the desirability of all forms of state sysems, democratic or otherwise: 'They say: "Undermine the whole conception of the State and then only we will have liberty worth having."' In Bhagat's conception, anti-statism (or astatism) was almost indistinguishable from anarchism. The post-revolutionary society was to be one with absolute individual freedom: a society created, maintained and experienced collectively, and where military and bureaucracy were no longer needed. The statement the HSRA revolutionaries made to the Commissioner of the Special Tribunal, for instance, declared: 'Revolutionaries by virtue of their altruistic principles are lovers of peace – a genuine and permanent peace based on justice and equity, not the illusory peace resulting from cowardice and maintained at the point of bayonets.' Here poorna swaraj transformed into an 'astatist' and 'aviolent' utopia for absolute political and human freedom even if the means of achieving this goal were violent or involved staging an armed revolution.

- ↑ *Jaffrelot, Christophe (22 September 2017), "The Making of Indian Revolutionaries (1885–1931)", ใน Bozarsian, Hamit; Batallion, Gilles; Jaffrelot, Christophe (บ.ก.), Revolutionary Passions: Latin America, Middle East and India, Routledge, p. 122, ISBN 978-1-351-37809-3,

The man who epitomizes this transition is Bhagat Singh. His Janus-like appearance reflected his two sources of inspiration (Bolshevism and Anarchism), the Marxist one becoming dominant by the late 1920s. But his evolution has been followed by others, including Shiv Verma, one of the founders of the HSRA. Verma, however, admitted in a 1986 article, that if in 1928 the firm resolution to turn away from 'anarchism and to make socialism an act of faith' had been taken, 'in practice, we held on to our old style of individual actions'

- Misra, Maria (2008), Vishnu's Crowded Temple: India Since the Great Rebellion, Yale University Press, p. 174, ISBN 978-0-300-14523-6,

In 1928 the Hindustan Socialist Republican Army (HSRA), an out-growth of the older revolutionary tradition of the Punjab, was founded in Lahore. Led by a charismatic 22-year-old student, Bhagat Singh, it departed from its pre-war terrorist lineage by adopting Marxist militant atheism as its ideology. The HSRA favoured acts of 'exemplary' revolutionary violence.

- Vaidik, Aparna (2021), Waiting for Swaraj: Inner Lives of Indian Revolutionaires, Cambridge University Press, p. 75, ISBN 978-1-00-903238-4,

Bhagat's use of the 'socialist' language in his later writings has created the assumption of him being a theoretically sophisticated author. Daniel Elam in his analysis of Bhagat's jail notebook, however, observes that there has been 'a politically sympathetic attempt to place Bhagat Singh in line with other radical writers, especially Antonio Gramsci'. While Bhagat was believed to be a singular anti-colonial 'author' figure of his jail notebook, the text was actually an assemblage of quotations, fragments and notes. He is also believed to have authored all the HSRA propaganda materials (pamphlets, posters, court statements and essays) that were in fact a product of brainstorming and collective authorial contribution of Shiv Verma, Bhagwati Charan Vohra, Yashpal and others.

- Raza, Ali (2020), Revolutionary Pasts: Communist Internationalism in Colonial India, Cambridge University Press, p. 107, ISBN 978-1-108-48184-7,

Bhagat Singh's hanging further galvanized a radical and militantly nationalistic politics that was in a state of ferment from the mid-1920s onwards.<Footnote 22: A point made, among others, by Kama Maclean in A Revolutionary History of Interwar India ...> It also lent an added urgency to the ongoing civil disobedient movement.

- Misra, Maria (2008), Vishnu's Crowded Temple: India Since the Great Rebellion, Yale University Press, p. 174, ISBN 978-0-300-14523-6,

- ↑ Moffat 2016, pp. 83, 89.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Moffat 2016, p. 83.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Maclean & Elam 2016, p. 28.

- ↑ Moffat 2016, p. 89.

- ↑ Moffat 2016, p. 84.

- ↑ Mittal & Habib (1982)

- ↑ Raza, Ali (2020), Revolutionary Pasts: Communist Internationalism in Colonial India, Cambridge University Press, p. 107, ISBN 978-1-108-48184-7,

His trial became the stuff of popular legend, as did his hanging — and those of his comrades Raj Guru and Sukhdev – in Lahore in March 1931. Bhagat Singh's death earned him the title of Shaheed-e-Azam (Great Martyr). He was not the only Shaheed who went to the gallows for his or her revolutionary activities, nor was he the only Shaheed-e-Azam.

หมายเหตุ

บรรณานุกรม

- Bakshi, S.R.; Gajrani, S.; Singh, Hari (2005), Early Aryans to Swaraj, vol. 10: Modern India, New Delhi: Sarup & Sons, ISBN 978-8176255370

- Datta, Vishwanath (2008). Gandhi and Bhagat Singh. Rupa & Co. ISBN 978-81-291-1367-2.[ลิงก์เสีย]

- Gaur, I.D. (2008), Martyr as Bridegroom, Anthem Press, ISBN 978-1-84331-348-9

- Grewal, J.S. (1998), The Sikhs of the Punjab, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-63764-0

- Gupta, Amit Kumar (September–October 1997), "Defying Death: Nationalist Revolutionism in India, 1897–1938", Social Scientist, 25 (9/10): 3–27, doi:10.2307/3517678, JSTOR 3517678 (ต้องรับบริการ)

- Habib, Irfan S.; Singh, Bhagat (2007). To make the deaf hear: ideology and programme of Bhagat Singh and his comrades. Three Essays Collective. ISBN 978-81-88789-56-6.

- MacLean, Kama (2015). A revolutionary history of interwar India : violence, image, voice and text. New York: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-021715-0.

- Maclean, Kama; Elam, J. David (2016), Revolutionary Lives in South Asia: Acts and Afterlives of Anticolonial Political Action, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-63712-7

- Moffat, Chris (2016), "Experiments in political truth", ใน Maclean, Kama; Elam, J. David (บ.ก.), Revolutionary Lives in South Asia: Acts and Afterlives of Anticolonial Political Action, Routledge, pp. 73–89, ISBN 978-1-317-63712-7

- Nair, Neeti (2011). Changing Homelands. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05779-1.

- Nair, Neeti (May 2009), "Bhagat Singh as 'Satyagrahi': The Limits to Non-violence in Late Colonial India", Modern Asian Studies, 43 (3): 649–681, doi:10.1017/S0026749X08003491, JSTOR 20488099, S2CID 143725577

- Nayar, Kuldip (2000), The Martyr Bhagat Singh: Experiments in Revolution, Har-Anand Publications, ISBN 978-81-241-0700-3

- Noorani, Abdul Gafoor Abdul Majeed (2001) [1996]. The Trial of Bhagat Singh: Politics of Justice. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-579667-4.

- Rana, Bhawan Singh (2005a), Bhagat Singh, Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd., ISBN 978-81-288-0827-2

- Rana, Bhawan Singh (2005b), Chandra Shekhar Azad (An Immortal Revolutionary of India), Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd., ISBN 978-81-288-0816-6

- Sanyal, Jatinder Nath; Yadav, Kripal Chandra; Singh, Bhagat; และคณะ, บ.ก. (2006) [1931], Bhagat Singh: a biography, Pinnacle Technology, ISBN 978-81-7871-059-4[ลิงก์เสีย][ไม่แน่ใจ ]

- Sharma, Shalini (2010). Radical Politics in Colonial Punjab: Governance and Sedition. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-45688-3.

- Singh, Bhagat; Hooja, Bhupendra (2007), The Jail Notebook and Other Writings, LeftWord Books, ISBN 978-81-87496-72-4

- Singh, Pritam (Fall 2007), "Review article" (PDF), Journal of Punjab Studies, 14 (2): 297–326, คลังข้อมูลเก่าเก็บจากแหล่งเดิม (PDF)เมื่อ 1 October 2015, สืบค้นเมื่อ 8 October 2013

- Singh, Randhir; Singh, Trilochan (1993). Autobiography of Bhai Sahib Randhir Singh: freedom fighter, reformer, theologian, saint and hero of Lahore conspiracy case, first prisoner of Gurdwara reform movement. Bhai Sahib Randhir Singh Trust.

- Tickell, Alex (2013), Terrorism, Insurgency and Indian-English Literature, 1830–1947, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-61840-6

- Waraich, Malwinder Jit Singh (2007). Bhagat Singh: The Eternal Rebel. Delhi: Publications Division. ISBN 978-8123014814.

- Waraich, Malwinder Jit Singh; Sidhu, Gurdev Dingh (2005). The hanging of Bhagat Singh : complete judgement and other documents. Chandigarh: Unistar.