生态形态学

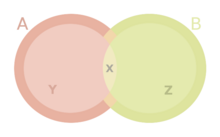

生态形态学(英語:ecomorphology或ecological morphology)是研究生物的生态角色与其适应形态(特别是解剖学形态)之间关系的交叉学科[1]。物种所处的栖息环境会直接或间接的影响其形态和生态位,而生态形态学的目标是鉴定不同物种间的这些区别[2],目前研究重点是通过测量行为性状的实际表现与适应度将形态与生态位相联系。

发展

生态形态学的起源可追溯至19世纪后期[3],当时形态学的重点是描述与比较不同物种的外形特征,主要用于鸟类分类。但在20世纪30年代和40年代,生态形态学因为新分类技术的兴起而出现学科衰落,但在50年代因为演化形态学的兴起又使得学科复兴[4]。高速摄影和X光摄影可以对身体部位的活动进行观察,而肌电图则可以监测肌肉活动,这使得形态学家可以更好的研究生物的行为细节。在50年代和60年代,生态学家也开始使用形态学测量来研究演化和生态问题,之后由华盛顿大学的詹姆斯·卡尔(James R. Karr)和佛罗里达州立大学的弗朗西斯·詹姆斯(Frances Crews James)两人在1975年首次使用了“生态形态学”一词[5]。随后脊椎动物形态和生态条件之间的联系被现代生态形态学的概念确定[6][7]。

与其它分科的关系

生态形态学与功能形态学

功能形态学(functional morphology)与生态形态学不同,主要关注因组织形态变化产生的特征变化[8];而生态形态学则主要关注周围生态系统和环境对体态的影响。功能形态学经常注重研究骨骼肌形态和运动功能(比如力量和关节灵活度)之间的关系[9],这意味着功能形态学研究可以在实验室内完成,但生态形态学则必须基于实地数据。此外,功能形态学研究本身无法提供足够数据来对物种对环境的适应做出结论,但其数据却可以被生态形态学充分利用[3]。很有代表性的例子是太阳鱼的颌骨结构、口腔尺寸和颚肌强度可以用来研究其进食习惯和可以适应的生态位[10]。

行为学

行为学(behavioural study)将功能形态学和生态形态学相结合,在生物学中的重要性与日俱增。这类研究曾展示鸟类觅食时的运动能力会影响其食谱偏好[11],渔业学和鸟类学中也经常使用生态形态学和行为学研究[12]。另有研究将消化道的生态形态学特征与食谱和进食量相联系[13],而消化道容积与代谢率之间有正向的相关联系。生态形态学研究也经常被用来通关判断宿主对栖息地的使用来鉴定寄生虫是否存在[14]。

应用

理解生态形态学对研究物种的生物多样性的起源和诱因十分必要。生态形态学通过理解生态位对形态变化的影响,可以展现不同的繁衍方式、感官能力和生存策略[15][16]。硬骨鱼类因为演化史很长、多样性很高、适应性强且具有数个生命阶段,常常被用来研究生态形态学[15],比如对非洲丽鱼形态多样性的研究[17]。

判断古栖息地

物种为了更好适应生态位而产生形态演化的历时可以用来帮助判定其史前栖息地的特征和性质。目前这种思路已经广泛应用在牛科化石的研究上[18],因为古牛类的化石的尺寸和辐射范围都十分客观[19]。牛类的系统发生树与其栖息地偏好之间很强的相关性说明形态学和栖息地之间做联系需要依赖分类阶元,而且有证据表明进一步研究之前存在的栖息地的生态形态特征有利于鉴定与栖息地相关的物种的系统发生学风险分析[19]。

演化形态学

演化形态学(evolutionary morphology)研究物种为了更好适应环境而出现的形态变化[3][16],主要手段是比较随着栖息地变化而产生的体态变化,而在演化形态史建立之前必须知道物种同源特征的背景历史。演化形态学只能为提供一个名义上的演化生物学解释,而全面解释物种演化则需要其生态史的深度了解。

目前有研究侧重将生态形态学与系统发生学和个体发生学结合来更好的理解演化形态学[15]。

生态形态学与栖息地偏好

有观点认为物种多样性和特定环境之间的相关联系未必是因为生态形态学因素,而是物种主动根据自身形态选择迁徙到更偏好的生态系统,然而目前并没有研究能够提供确凿证据支持这种理论。有研究试图用身体形态预测鱼类对栖息地的偏好,但没有发现明显差别[20][21]。

另见

参考

- ^ Ecomorphology. About.com. [2013-05-21]. (原始内容存档于2013-05-14).

- ^ Norton, Stephen. The role of ecomorphological studies in the comparative biology of fishes (PDF). University of South Florida. [2024-09-30]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2018-09-20).

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Bock, W. J. 1994. Concepts and methods in ecomorphology. Journal of Biosciences 19:403–413. [1]

- ^ Beer, G. 1954. Archaeopteryx and evolution. The Advancement of Science 11: 160–170. [2] (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Karr, James R.; James, Frances C. Eco-morphological configurations and convergent evolution of species and communities. Ecology and Evolution of Communities. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 1975: 258–291. ISBN 9780674224445.

- ^ Bock, W. 1977. Toward an ecological morphology. Vogelwarte 29: 127–135

- ^ Leisler, B. 1977. Morphological Aspects of Ecological Specializations in Bird Genera. American Zoologist 19(3): 1014–1014.[3]

- ^ Bock, W. Van Walhert, J. 1965. The role of adaptive mechanisms in the origin of higher levels of organisation. Systematic Biology 14(4): 272–287. [4][失效連結]

- ^ Bock, W., G. Lanzavecchia, and R. Valvassori. 1991. Levels of complexity and organismal organization. Selected Symposia and Monographs UZI. Vol 5 181–212. [5]

- ^ Wainwright, P. C. Ecological Explanation through Functional Morphology: The Feeding Biology of Sunfishes. Ecology. 1996, 77 (5): 1336–1343. Bibcode:1996Ecol...77.1336W. JSTOR 2265531. doi:10.2307/2265531.

- ^ Moermond, T., and J. Denslow. 1983. Fruit choice in neotropical birds: effects of fruit type and accessibility on selectivity. The Journal of Animal Ecology 52(2): 407–420. [6] (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Sibbing, F., L. Nagelkerke, and J. Osse. 1994. Ecomorphology as a tool in fisheries-Identification and ecotyping of Lake Tana Barbs (Barbus-Intermedius COmplex), Ethiopia. Netherlands Journal of Agricultural Science 42:77–85. Royal Netherlands Soc Agr Sci.[7]

- ^ Griffen, B. D., and H. Mosblack. 2011. Predicting diet and consumption rate differences between and within species using gut ecomorphology. The Journal of animal ecology 80:854–63.[8]

- ^ Goodman, B. A., and P. T. J. Johnson. 2011. Ecomorphology and disease: cryptic effects of parasitism on host habitat use, thermoregulation, and predator avoidance. Ecology 92:542–548.[9]

- ^ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Norton, S. F., J. J. Luczkovich, and P. J. Motta. 1995. The role of ecomorphological studies in the comparative biology of fishes. Environmental Biology of Fishes 44:287–304.[10]

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Moreno-Arias, Rafael A.; Bloor, Paul; Calderón-Espinosa, Martha L. Evolution of ecological structure of anole communities in tropical rain forests from north-western South America. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2020, 190 (1): 298–313 [2024-09-30]. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa006. (原始内容存档于2023-03-15).

- ^ Fryer, G. T. and Iles, T. D. The cichlid fishes of the great lakes of Africa: their biology and evolution. 1972. Oliver and Boyd, Cornell University.[11] (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Plummer, T. W., Bishop, L. C., Hertel, F. 2008. Habitat preference of extant African bovids based on astragalus morphology: operationalizing ecomorphology for palaeoenvironmental reconstruction. Journal of Archaeological Science 35(11): 3016–3027 [12]

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Scott, R. S., and W. A. Barr. 2014. Ecomorphology and phylogenetic risk: Implications for habitat reconstruction using fossil bovids. Journal of human evolution 73:47–57 [13]

- ^ Chan, M. D. 2001. Fish ecomorphology: predicting habitat preferences of stream fishes from their body shape. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.[14]

- ^ Betz, Oliver. Ökomorphologie: Integration von Form, Funktion und Ökologie bei der Analyse morpho-logischer Strukturen [Ecomorphology: Integration of form, function, and ecology in the analysis of morphological structures]. Mitteilungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Allgemeine und Angewandte Entomologie. 2006, 15: 409–416 (German).