菌異營

菌異營(英語:Myco-heterotrophy),或称真菌异养型,是植物與真菌的一種共生關係,此關係中植物不行光合作用,而是與真菌形成菌根後,透過寄生真菌取得全部或部分的有機養分。菌異營被認為是一種欺詐行為,行菌異營的植物靠真菌取得有機養分而得以在樹林下方等缺乏光線的環境生存,這些植物有時被稱為「菌根欺詐者」(mycorrhizal cheaters)[2]。

交互作用

絕對菌異營植物(obligate myco-heterotroph)因失去了葉綠素或整個光系統而完全失去了行光合作用的能力,只從寄生的真菌處獲得有機養分,而兼性菌異營植物(facultative myco-heterotrophy)本身仍有行光合作用的能力,但從寄生的真菌處獲得額外的養分來源[2]。有些蘭科的植物在生活史的某一階段是絕對菌異營者,沒有行光合作用的能力,其他階段則轉為兼性菌異營者或失去菌異營的行為[3]。不過並非所有不行光合作用的植物都行菌異營,菟絲子等植物沒有葉綠體,透過直接寄生其他植物取得養分,即非菌異營者[4]。

過去人們誤認為這些不行光合作用的植物是像真菌一樣,直接分解環境中的有機物質以取得養分,而將它們稱為腐生植物,現在知道這些植物並沒有直接分解有機物質的能力,只能透過菌異營或直接寄生其他植物等寄生的方式取得養分[5][6]。

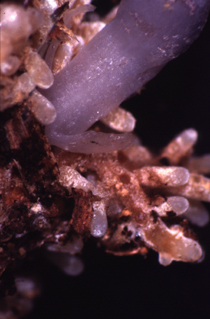

菌異營中,植物與真菌交互作用的部位為植物的根與真菌的菌絲體,與菌根相仿,也被認為是由菌根演化而來的一種交互作用[5]。在菌根中,真菌幫助植物吸收水分與無機鹽,而有機物流動的方向是從植物流向真菌,但在菌異營中流向相反,是由真菌流向植物[7][8],因此菌異營的植物算是一種外寄生物(epiparasites)[5][6][9]。且由於許多菌根在底下都會透過菌絲相連,形成稱為菌根網的複雜結構[10],使植物用以和其他植物交換物質[6],許多菌異營中被寄生的真菌也是從其他植物的菌根中取得有機養分的,在這個系統中,菌異營的植物是一個欺詐者,從系統中獲取有機養分,卻沒有提供相應回報[5]。

也有些菌異營的植物寄生於分解環境中有機物為生的腐生真菌[11]。另外也有研究顯示有些演化上與菌異營植物親緣接近,但本身能正常行光合作用的綠色植物也是兼性菌異營者,即它們以光合作用取得有機養分之外,還能從真菌處獲取額外養分[12][13]。

在寄生真菌之餘,菌異營的植物可能有刺激真菌生長的機制,有研究顯示鬚腹菌屬真菌可以同時與菌異營的血晶兰以及非菌異營的紅果冷杉形成菌根,此共生關係中,血晶兰可以刺激真菌與紅果冷杉的生長,不過具體機制亦不明[14]。

物種

許多植物都演化出了菌異營的交互作用,水晶蘭亞科、不行光合作用的蘭科植物、甚至屬於苔蘚植物的腐生苔屬和屬於裸子植物的寄生松屬均是菌異營者[2],蘭科植物與真菌形成的蘭菌根便是菌異營的經典例子,是蘭科植物種子萌發與生長不可或缺的構造[15]。兼性菌異營在龍膽科植物中相當常見,也有部分屬如Voyria是絕對菌異營者。另外有些蕨類與石松的配子體世代也行菌異營[3][6][16]。而被寄生的真菌通常是可以形成菌根,而有很大的能量潛力可以吸取的種類,不過也有研究顯示有菌異營植物可以寄生腐生真菌,甚至菌絲體網絡複雜的植物病原菌蜜環菌[6]。形成菌異營的菌根屬於外菌根、叢枝菌根與蘭菌根者皆有[17],行菌異營的植物與真菌相當多樣,且在分類上分屬不同類群,表示菌異營是從菌根多次平行演化而出現的交互作用[17]。

演化

菌異營可能是由互利共生的菌根演化而來,許多例子中,菌異營的演化過程可能是植物細胞外的外菌根穿透植物細胞形成內菌根,有機物的流向再經由不明機制逆轉所致[2]。部分菌異營植物可能是由原本就生存在樹林下方、缺乏光線的環境的綠色植物演化而來[2]。而由於許多在菌異營植物中,真菌對種子萌發的階段相當重要,有假說認為菌異營在演化早期可能是真菌在植物種子萌發時先提供其有機養分作為投資,待植物長成可以行光合作用後再取得有機養分作為回報,而形成互利共生的作用模式,之後有些植物漸演化出長成後避免向真菌輸入有機養分的機制,即成為絕對菌異營植物[2]。

參考資料

- ^ Yang, S; DH Pfister. Monotropa uniflora plants of eastern Massachusetts form mycorrhizae with a diversity of russulacean fungi. Mycologia. 2006, 98 (4): 535–540 [2018-08-14]. PMID 17139846. doi:10.3852/mycologia.98.4.535. (原始内容存档于2009-07-19).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Martin I. Bidartondo. The evolutionary ecology of myco-heterotrophy 167 (2). New Phytologist: 335-352. 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01429.x.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Leake JR. The biology of myco-heterotrophic ('saprophytic') plants. 127. New Phytologist: 171–216. 1994. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb04272.x.

- ^ Dawson JH, Musselman LJ, Wolswinkel P, Dörr I. Biology and control of Cuscuta 6. Reviews of Weed Science: 265–317. 1994.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Bidartondo, Martin I. The evolutionary ecology of myco-heterotrophy. New Phytologist. 2005-04-12, 167 (2): 335–352. ISSN 0028-646X. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01429.x.

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Plants parasitic on fungi: unearthing the fungi in myco-heterotrophs and debunking the ‘saprophytic’ plant myth. Mycologist. 2005-08-01, 19 (3): 113–122. ISSN 0269-915X. doi:10.1017/S0269-915X(05)00304-6.

- ^ Trudell SA, Rygiewicz PT, Edmonds RL. Nitrogen and carbon stable isotope abundances support the myco-heterotrophic nature and host-specificity of certain achlorophyllous plants 160. New Phytologist: 391–401. 2003. doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00876.x.

- ^ Bidartondo MI, Burghardt B, Gebauer G, Bruns TD, Read DJ. Changing partners in the dark: isotopic and molecular evidence of ectomycorrhizal liaisons between forest orchids and trees 271. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, series B: 1799–1806. 2004. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2807.

- ^ Selosse M-A, Weiss M, Jany J, Tilier A. Communities and populations of sebacinoid basidiomycetes associated with the achlorophyllous orchid Neottia nidus-avis (L.) L.C.M. Rich. and neighbouring tree ectomycorrhizae 11. Molecular Ecology: 1831–1844. 2002. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01553.x.

- ^ Peter Kennedy. Common Mycorrhizal Networks: An Important Ecological Phenomenon. MykoWeb (originally published on Mycena News). November 2005 [2012-01-19]. (原始内容存档于2012-02-04).

- ^ Martos F, Dulormne M, Pailler T, Bonfante P, Faccio A, Fournel J, Dubois M-P, Selosse M-A. Independent recruitment of saprotrophic fungi as mycorrhizal partners by tropical achlorophyllous orchids 184. New Phytologist: 668–681. 2009. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02987.x.

- ^ Gebauer G, Meyer M. 15N and 13C natural abundance of autotrophic and myco-heterotrophic orchids provides insights into nitrogen and carbon gain from fungal association 160. New Phytologist: 209–223. 2003. doi:10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00872.x.

- ^ Selosse M-A, Roy M. Green plants eating fungi: facts and questions about mixotrophy 14. Trends in Plant Sciences: 64–70. 2009. PMID 19162524. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2008.11.004.

- ^ Bidartondo MI, Kretzer AM, Pine EM, Bruns TD. High root concentration and uneven ectomycorrhizal diversity near Sarcodes sanguinea (Ericaceae): a cheater that stimulates its victims? 87 (12). American Journal of Botany: 1783-1788. 2000. doi:10.2307/2656829.。

- ^ Smith, S. E.; Read, D. J.; Harley, J. L. Mycorrhizal symbiosis 2nd. San Diego, Calif.: Academic Press. 1997. ISBN 0126528403. OCLC 35637899.

- ^ Taylor DL, Bruns TD, Leake JR, Read DJ. Mycorrhizal specificity and function in myco-heterotrophic plants. Sanders IR, van der Heijden M (编). Ecological Studies (PDF). Mycorrhizal Ecology 157 (Springer-Verlag). 2002: 375–414 [2018-08-14]. ISBN 3-540-00204-9. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2017-05-31).

- ^ 17.0 17.1 Imhof S. Arbuscular, ecto-related, orchid mycorrhizas—three independent structural lineages towards mycoheterotrophy: implications for classification? 19 (6). Mycorrhiza: 357–363. 2009 [2018-08-18]. (原始内容存档于2018-08-18).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||