越語支

| 越语支 | |

|---|---|

| 地理分佈 | 东南亚 |

| 谱系学分类 | 南亚语系

|

| 原始語言 | 原始越芒语 |

| 分支 | |

| – | |

| Glottolog | viet1250[1] |

越语支 | |

越语支(Vietic)是南亚语系的一个分支。此语支曾被称为越芒语支、安南-芒语支及越南-芒语支。“越语支”之名于1992年由Hayes提出,他提议将“越芒语支”进行重新定义,成为越语支的一个分支,仅仅包含拥有越南语和芒语两种语言,而使用越芒語支的各民族也被稱為越芒民族。

许多越语支语言拥有声调或喉音,這是汉语及侗台语的特征,在越语支以外的其他南亚语系分支中所沒有的。

今日的越南语中包含汉语影响的特征,尤其是词汇及声调系统。越南语词汇中包含30%至60%的汉越词,不包括来自中国的借译。

起源

然而,越语支的起源仍是一个饱含争议的话题。基于语言多样性的理论认为越语支最可能的故乡是在今日老挝波里坎塞省、甘蒙省及越南乂安省和广平省部分地区。越语支的时间深度有2500-2000年(Chamberlain 1998)、3500年(Peiros 2004)、约3000年(Alves 2020)几说。[5][6]:xix尽管如此,古基因学证明,远在东山文化之前,红河三角洲的住民就已经操南亚语系语言:逢元文化缦泊遗址(1800 BC)的主体基因与现代南亚语使用者的基本相似;[7][8]同时,东山文化𡶀纳遗址的“混合基因”与“中国傣族、泰国壮侗语系语言使用者、越南南亚语系语言使用者,包括京族”有着密切联系;[9]因此,“越语支的扩张肯定是从红河三角洲开始的。至于南部的高多样性,则尚待其它假说。”[10]

越南语

越南语在19世纪中叶被识别为南亚语系语言。现代越南语丢失了许多原始南亚语音系、词法特征,还从汉语借来大量词汇。然而认为越南语和高棉语比和汉语或傣族语更近的说法却经久不衰。大多数语言学家认为这些语言类型学上的相似性不是因为有共同祖先,而是由语言接触产生的。[11]

Chamberlain (1998)认为红河三角洲地区本是傣语使用者聚居区,在7-9世纪间被从越南中部来的越语移民占据,这一地区也是今日最异相、最保守的中北部越南语方言分布地区。因此,越南语起源地也位于红河以南。[12]

另一方面,Ferlus (2009)发现,东山文化特有的杵、桨和炒糯米用的锅对应北部(越芒语)、中部越语(哲土语)的词汇创新。这些新词被证明是从原始动词派生而来的,而不是借来的词汇。北越语目前的分布也与东山文化的区域相对应。由此,Ferlus得出结论,北部越语是东山文化的直系后代,他们自公元前1千纪以来一直居住在红河三角洲南部和越南中北部。[3]

John Phan (2013, 2016)[13][14]进一步宣称,曾有过一种分布在红河河谷的“中古安南汉语”,后来被同时共存的原始越芒语吸收,它的一种异相方言后来演化成越南语。ref>Phan, John. "Re-Imagining 'Annam': A New Analysis of Sino–Viet–Muong Linguistic Contact" in Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, Volume 4, 2010. pp. 22-3</ref>中古安南汉语属于中国西南中古汉语方言连续体的一部分,最终演化成瓦乡话、贺州九都土話、南部平话和湘语。[14]Phan (2013)列出三类主要的汉越词类型:

分布

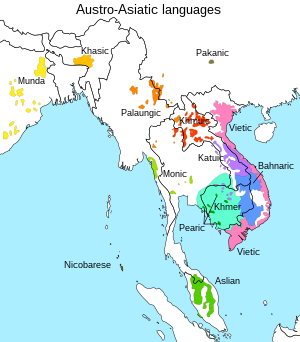

越语支使用者分布在老挝部分地区和越南中北部(Chamberlain 1998)。许多人被分为芒族、茹廊族和源族。Chamberlain (1998)列出老挝境内越语支使用者居住地。[15]基于一首田野调查数据的概览由Michel Ferlus主持编写。[16]

- 源语:甘蒙省布拉帕县Pak Phanang版

- Liha、Phong、Toum:波里坎塞省坎格县;可能来自乂安省北部/坎格县交界附近地区

- Ahoe:本居于甘蒙省纳开县Na Tane区和波里坎塞省坎格县Na Va版;越南战争期间迁徙至甘蒙省欣本县,后被安置在纳开高原上的Nakai Tay(39户)和Sop Hia(20户)。

- 他文语(Ahao、Ahlao方言):Lak Xao附近几个村庄;可能来自Na Heuang附近

- 哲语:甘蒙省布拉帕县Na Phao版和Tha Sang;可能在Pha Song、Vang Nyao、Takaa亦有分布;从越南、Hin Nam No迁来

- Atel:Nam Sot的Tha Meuang(主要为麻楞族);来自Houay Kanil地区

- Thémarou:南屯河的Vang Chang;Nam Noy附近的Ban Soek

- Makang:波里坎塞省坎格县Na Kadok(主要为Saek族);来自Sot上游地区

- 麻楞语:Nam Sot的Tha Meuang

- “Salang”:甘蒙省布拉帕县Xe Neua版

- Atop:波里坎塞省坎格县Na Thone(主要为Tai Theng族);来自Sot上游地区

- Mlengbrou:邻近Nam One;后来被重新安置至Ak山脉甘蒙省纳马拉胶县一侧,现在生活在纳马拉胶县Sang版(主要Yooy族)

- 克里语:Maka版

在越南,部分越语支山地民族,如Arem、Rục、Maliêng、Mày(Cươi)族被安置到Cu Nhái(广平省西部或河静省香溪县西南部)。越南也有册族。

下表列出不同越语支族群的生活方式。不同于相邻的傣语族群,许多越语支族群并不种水稻。

| 生活方式 | 越语支族群 |

|---|---|

| 小群觅食游牧民族 | Atel、Thémarou、Mlengbrou、(哲语?) |

| 采猎贸易部落→新兴临时烧垦定居者 | Arao、麻楞语、Malang, Makang、Tơe、Ahoe、Phóng |

| 烧垦种植者,每2–3年在已有村落间移动 | 克里语 |

| 烧垦、水稻定居混合 | Ahao、Ahlao、Liha、Phong、Toum |

语言

越南语声调与同一语系其他语言非声调特征的规则对应被认为是历史语言学发展路上的一块里程碑。[17]越语支的类型学特征介于汉语、傣语和一般南亚语系语言之间,有着复杂的声调、复杂的辅音系统、C(g)VC或CCVC音节结构、单音节或多音节-分析或黏着的语法特征。[18][19]

- 阿楞语:缺乏越语支普遍的气声,但有声门化的韵尾辅音。

- 土语: 老挝封语、越南土语

- 他文语:在韵尾展现出清与气声、无标记与声门化的4重对立。这和比尔语支的情况很像,不过它的声门化落在元音上。

- 哲语:方言连续体;有4个音区,与他文语调音方法互相对应

- 麻楞语:有一种他文语特色的4向音区系统。

- 越芒语:越南语和芒语,共享75%的基础词汇,都有5–6个声调。与其他越语支语言规则对应:3对高低调对应祖语声母浊音、清音(阴阳分调);平调对应开音节或鼻音结尾的音节;高升调和低降调对应塞音结尾的音节,后来消失;降调对应擦音结尾的音节,后来也消失了;声门化塞音调对应以声门化塞音结尾的音节,后来声门化消失。

系属分类

Sidwell (2021)

Paul Sidwell给出越语支如下系属分类。越异质的分支越靠前。[20][21]

- 他文–麻令:克里语、麻楞语、麻令语、Ahao/Ahlao、他文语

- 哲语:阿楞语、册方言、浊方言、眉方言

- 封–Liha(Pong–Toum[22]):Phong、Toum、Liha

- 土语:土语

- 越芒语:越南语、芒语、源语

他文-麻令群有着最古老的词汇、音韵特征,哲语*-r、*-l韵尾合流为*-l。[20]

Chamberlain (2018)

Chamberlain (2018:9)[23]将越语支称作克里-门语,认为有门-土和侬-屯两大支。

- 克里-门语支

- 门-土语群

- 侬-屯语群

Sidwell (2015)

基于Ferlus (1982, 1992, 1997, 2001)的比较研究和Phan (2012)对芒语的新研究,[24]Sidwell (2015)[25]指出,芒语实际上是个并系群,且是越南语内部的亚群。Sidwell (2015)的分类如下:

越语支

- 越芒语:越南语、Mường Muốt、Mường Nàbái、Mường Chỏi等

- Pong-Toum:Đan Lai、Hung、Toum、Cuôi等

- 哲语

- 东部:Mãliềng、麻楞语、阿楞语、克里语、哲语(Mày, Rụt, Sách, Mụ Già)等

- 西部:他文语、Pakatan等

Chamberlain (2003)

下列Chamberlain (2003:422)越语支语言分类方案来自Sidwell (2009:145)的引用。不同于过去的分类,其中包括第六个南支,含新发现的克里语。

动物生肖年名

Michel Ferlus(1992, 2013)[27][28]发现高棉曆以12年为一周期有生肖循环,它还产生了泰国阴历的动物周期年名,实际上均来自越芒语对动物的称呼。Ferlus主张动物生肖年名来自一种北部越语,古高棉语“蛇”m.saɲ的元音对应越芒语/a/,而不是南部越语的/i/。

| 动物 | 泰语生肖年名 | 高棉语 IPA | 现代高棉语 | 高棉帝国高棉语 | 古高棉语 | 原始越芒语 | 越南语 | 芒语 | 土语 | 克里语 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 鼠 | Chuat (ชวด) | cuːt | jūt (ជូត) | ɟuot | ɟuot | *ɟuot | chuột | chuột[a] /cuot⁸/ | - | - |

| 牛 | Chalu (ฉลู) | cʰlou | chlūv (ឆ្លូវ) | caluu | c.luː | *c.luː | trâu | tlu /tluː¹/[b] | kluː¹ | săluː² |

| 虎 | Khan (ขาล) | kʰaːl | khāl (ខាល) | kʰaal | kʰa:l | *k.haːlˀ | khái[c] | khảl /kʰaːl³/ | kʰaːl³ | - |

| 兔 | Thɔ (เถาะ) | tʰɑh | thoḥ (ថោះ) | tʰɔh | tʰɔh | *tʰɔh | thỏ | thó /tʰɔː⁵/ | tʰɔː³ | - |

| 龍 | Marong (มะโรง) | roːŋ | roṅ (រោង) | marooŋ | m.roːŋ | *m.roːŋ | rồng | rồng /roːŋ²/ | - | roːŋ¹ |

| 蛇 | Maseng (มะเส็ง) | mə̆saɲ | msāñ' (ម្សាញ់) | masaɲ | m.saɲ | *m.səɲˀ | rắn | thẳnh /tʰaɲ³/[d] | siŋ³ | - |

| 馬 | Mamia (มะเมีย) | mə̆miː | mamī (មមី) | mamia | m.ŋɨa | *m.ŋǝːˀ | ngựa | ngữa /ŋɨa⁴/ | - | măŋəː⁴ |

| 羊 | Mamɛɛ (มะแม) | mə̆mɛː | mamæ (មមែ) | mamɛɛ | m.ɓɛː | *m.ɓɛːˀ | -[e] | bẻ /ɓɛ:³/ | - | - |

| 猴 | Wɔɔk (วอก) | vɔːk | vak (វក) | vɔɔk | vɔːk | *vɔːk | voọc[f] | voọc /vɔːk⁸/ | vɔːk⁸ | - |

| 雞 | Rakaa (ระกา) | rə̆kaː | rakā (រកា) | rakaa | r.kaː | *r.kaː | gà | ca /kaː¹/ | kaː¹ | kaː¹ |

| 狗 | Jɔɔ (จอ) | cɑː | ca (ច) | cɔɔ | cɔː | *ʔ.cɔːˀ | chó | chỏ /cɔː³/ | cɔː³ | cɔː³ |

| 豬 | Kun (กุน) | kao/kol | kur (កុរ) | kur | kur | *kuːrˀ | cúi[g] | củi /kuːj³/ | kuːl⁴ | kuːl⁴ |

阅读更多

- Alves, Mark J. Historical Ethnolinguistic Notes on Proto-Austroasiatic and Proto-Vietic Vocabulary in Vietnamese. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 2020, 13 (2): xiii–xlv. hdl:10524/52472.

- Alves, Mark. 2020. Data for Vietic Native Etyma and Early Loanwords (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- Alves, Mark J. 2016. Identifying Early Sino-Vietnamese Vocabulary via Linguistic, Historical, Archaeological, and Ethnological Data, in Bulletin of Chinese Linguistics 9 (2016):264-295.

- Alves, Mark J. 2017. Etymological research on Vietnamese with databases and other resources. Ngôn Ngữ Học Việt Nam, 30 Năm Đổi Mới và Phát Triển (Kỷ Yếu Hội Thảo Khoa Học Quốc Tế), 183-211. Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Khoa Học Xã Hội.

- Alves, Mark J. (2003). Ruc and Other Minor Vietic Languages: Linguistic Strands Between Vietnamese and the Rest of the Mon-Khmer Language Family (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). In Papers from the Seventh Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, ed. by Karen L. Adams et al. Tempe, Arizona, 3-19. Arizona State University, Program for Southeast Asian Studies.

- Barker, M. E. (1977). Articles on Proto-Viet–Muong. Vietnam publications microfiche series, no. VP70-62. Huntington Beach, Calif: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Chamberlain, J.R. 2003. Eco-Spatial History: a nomad myth from the Annamites and its relevance for biodiversity conservation. In X. Jianchu and S. Mikesell, eds. Landscapes of Diversity: Proceedings of the III MMSEA Conference, 25–28 August 2002. Lijiand, P. R. China: Center for Biodiversity and Indigenous Knowledge. pp. 421–436.

- Miyake, Marc. 2014. Black and white evidence for Vietnamese phonological history (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- Miyake, Marc. 2014. Soni linguae capitis. (Parts 1 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), 2-4 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).)

- Miyake, Marc. 2014. What the *-hɛːk is going on? (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Miyake, Marc. 2013. A 'wind'-ing tour (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- Miyake, Marc. 2010. Muong rhotics (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- Miyake, Marc. 2010. A meaty mystery: did Vietnamese have voiced aspirates? (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Nguyễn, Tài Cẩn. (1995). Giáo trình lịch sử ngữ âm tiếng Việt (sơ thảo) (Textbook of Vietnamese historical phonology). Hà Nội: Nhà Xuất Bản Gíao Dục.

- Pain, Frederick. "Giao Chỉ" (Jiaozhi 交趾) as a Diffusion Center of Middle Chinese Diachronic Changes: Syllabic Weight Contrast and Phonologisation of Its Phonetic Correlates. Tsing Hua Journal of Chinese Studies. 2020, 50 (3): 356–437. doi:10.6503/THJCS.202009_50(3).0001.

- Peiros, Ilia J. 2004. Geneticeskaja klassifikacija aystroaziatskix jazykov. Moskva: Rossijskij gosudarstvennyj gumanitarnyj universitet (doktorskaja dissertacija).

- Trần Trí Dõi (2011). Một vài vấn đề nghiên cứu so sánh - lịch sử nhóm ngôn ngữ Việt - Mường [A historical-comparative study of Viet-Muong group]. Hà Nội: Nhà xuất bản Đại Học Quốc Gia Hà nội. ISBN 978-604-62-0471-8

- Sidwell, Paul (2009). Classifying the Austroasiatic languages: history and state of the art. LINCOM studies in Asian linguistics, 76. Munich: Lincom Europa.

参考

- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian (编). Vietic. Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. 2016.

- ^ Sagart, Laurent, The expansion of Setaria farmers in East Asia, Past human migrations in East Asia: matching archaeology, linguistics and genetics: 141–145, 2008 [2022-01-29], (原始内容存档于2021-08-15),

The cradle of the Vietic branch of Austroasiatic is very likely in north Vietnam, at least 1000km to the south‑west of coastal Fújiàn

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Ferlus, Michael. A Layer of Dongsonian Vocabulary in Vietnamese. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 2009, 1: 105 [2022-01-29]. (原始内容存档于2022-03-27).

- ^ Alves, Mark. Data from Multiple Disciplines Connecting Vietic with the Dong Son Culture. 2019-05-10 [2022-01-29]. (原始内容存档于2023-03-26).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Chamberlain, J.R. 1998, "The origin of Sek: implications for Tai and Vietnamese history (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)", in The International Conference on Tai Studies, ed. S. Burusphat, Bangkok, Thailand, pp. 97-128. Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidol University.

- ^ Alves 2020.

- ^ Lipson, Mark; Cheronet, Olivia; Mallick, Swapan; Rohland, Nadin; Oxenham, Marc; Pietrusewsky, Michael; Pryce, Thomas Oliver; Willis, Anna; Matsumura, Hirofumi; Buckley, Hallie; Domett, Kate; Hai, Nguyen Giang; Hiep, Trinh Hoang; Kyaw, Aung Aung; Win, Tin Tin; Pradier, Baptiste; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Candilio, Francesca; Changmai, Piya; Fernandes, Daniel; Ferry, Matthew; Gamarra, Beatriz; Harney, Eadaoin; Kampuansai, Jatupol; Kutanan, Wibhu; Michel, Megan; Novak, Mario; Oppenheimer, Jonas; Sirak, Kendra; Stewardson, Kristin; Zhang, Zhao; Flegontov, Pavel; Pinhasi, Ron; Reich, David. Ancient genomes document multiple waves of migration in Southeast Asian prehistory. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)). 2018-05-17, 361 (6397): 92–95. Bibcode:2018Sci...361...92L. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 6476732

. PMID 29773666. bioRxiv 10.1101/278374

. PMID 29773666. bioRxiv 10.1101/278374  . doi:10.1126/science.aat3188.

. doi:10.1126/science.aat3188.

- ^ Corny, Julien, et al. 2017. "Dental phenotypic shape variation supports a multiple dispersal model for anatomically modern humans in Southeast Asia." Journalof Human Evolution 112 (2017):41-56. cited in Alves, Mark (2019-05-10). "Data from Multiple Disciplines Connecting Vietic with the Dong Son Culture". Conference: "Contact Zones and Colonialism in Southeast Asia and China's South (~221 BCE - 1700 CE)"At: Pennsylvania State University

- ^ McColl et al. 2018. "Ancient Genomics Reveals Four Prehistoric Migration Waves into Southeast Asia". Preprint. Published in Science. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/278374v1 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) cited in Alves, Mark (2019-05-10). "Data from Multiple Disciplines Connecting Vietic with the Dong Son Culture". Conference: "Contact Zones and Colonialism in Southeast Asia and China's South (~221 BCE - 1700 CE)"At: Pennsylvania State University

- ^ Alves, Mark (2019-05-10). "Data from Multiple Disciplines Connecting Vietic with the Dong Son Culture" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Conference: "Contact Zones and Colonialism in Southeast Asia and China's South (~221 BCE - 1700 CE)"At: Pennsylvania State University

- ^ LaPolla, Randy J.. (2010). "Language Contact and Language Change in the History of the Sinitic Languages." Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(5), 6858-6868.

- ^ *Chamberlain, James R. 1998. "The Origin of the Sek: Implications for Tai and Vietnamese History (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)". Journal of the Siam Society 86.1 & 86.2: 27-48.

- ^ Phan, John. 2013. Lacquered Words: the Evolution of Vietnamese under Sinitic Influences from the 1st Century BCE to the 17th Century CE (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Ph.D. dissertation: Cornell University.

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Phan, John D. & de Sousa, Hilário. 2016. A preliminary investigation into Proto-Southwestern Middle Chinese (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). (Paper presented at the International workshop on the history of Colloquial Chinese – written and spoken, Rutgers University, New Brunswick NJ, 11–12 March 2016.)

- ^ Welcome to World Bank Intranet (PDF). [2022-01-29]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-03-03).

- ^ Ferlus, Michel. 1996. Langues et peuples viet-muong. Mon-Khmer Studies 26. 7–28.

- ^ Ferlus, Michel. 2004. The Origin of Tones in Viet-Muong. In Somsonge Burusphat (ed.), Papers from the Eleventh Annual Conference of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 2001, 297–313. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona State University Programme for Southeast Asian Studies Monograph Series Press.

- ^ See Alves 2003 on the typological range in Vietic.

- ^ The following information is taken from Paul Sidwell's lecture series on the Mon–Khmer languages.[1] (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ 20.0 20.1 Sidwell, Paul. Classification of MSEA Austroasiatic languages. The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia. De Gruyter. 2021: 179–206. ISBN 9783110558142. doi:10.1515/9783110558142-011.

- ^ Sidwell, Paul and Mark Alves. In preparation. A Phylogenetic Analysis of Vietic.

- ^ Alves, Mark J. Typological profile of Vietic. The Languages and Linguistics of Mainland Southeast Asia. De Gruyter. 2021: 469–498. ISBN 9783110558142. doi:10.1515/9783110558142-022.

- ^ Chamberlain, James R. 2018. A Kri-Mol (Vietic) Bestiary: Prolegomena to the Study of Ethnozoology in the Northern Annamites (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Kyoto Working Papers on Area Studies (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) No. 133. Kyoto: Kyoto University.

- ^ Phan, John. 2012. "Mường is not a subgroup: Phonological evidence for a paraphyletic taxon in the Viet-Muong sub-family." In Mon-Khmer Studies, no. 40, pp. 1-18., 2012.

- ^ Sidwell, Paul. 2015. "Austroasiatic classification." In Jenny, Mathias and Paul Sidwell, eds (2015). The Handbook of Austroasiatic Languages, 144-220. Leiden: Brill.

- ^ Phan, John D. 2012. "Mường is not a subgroup: Phonological evidence for a paraphyletic taxon in the Viet-Muong sub-family." Mon-Khmer Studies 40:1-18.

- ^ Ferlus, Michel. 1992. "Sur L’origine Des Langues Việt-Mường (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)." In The Mon-Khmer Studies Journal, 18-19: 52-59. (in French)

- ^ Michel Ferlus. The sexagesimal cycle, from China to Southeast Asia (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). 23rd Annual Conference of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, May 2013, Bangkok, Thailand. <halshs-00922842v2>

外部链接

- La Vaughn Hayes Vietic Digital Archives (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- SEAlang Project: Mon–Khmer languages. The Vietic Branch (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Sidwell (2003)

- Endangered Languages of Mainland Southeast Asia (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- http://projekt.ht.lu.se/rwaai (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) RWAAI (Repository and Workspace for Austroasiatic Intangible Heritage)

- http://hdl.handle.net/10050/00-0000-0000-0003-670D-C@view Vietic languages in RWAAI Digital Archive