Avestan period

| Part of a series on |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

|

|

|

The Avestan period (c. 1500 – c. 500 BCE)[note 1] is the period in the history of the Iranians when the Avesta was produced.[1] It saw important contributions to both the religious sphere, as well as to Iranian mythology and its epic tradition.[2]

Scholars can reliably distinguish between two different linguistic strata in the Avesta; Old Avestan and Young Avestan, which are interpreted as belonging to two different stages in the development of the Avestan language and society.[3] The Old Avestan society is the one to which Zarathustra himself and his immediate followers belonged. The Young Avestan society is less clearly delineated and reflects a larger time span.[4]

There is a varying level of agreement on the chronological and geographical boundaries of the Avestan period. Regarding the geographical extent of the Avesta, modern scholarship agrees that it reflects the eastern portion of Greater Iran.[5] Regarding the chronological extent, scholarship initially focused on a late chronology, that places Zarathustra in the 6th century BCE. More recently an early chronology, that places him several centuries earlier, has become widely accepted.[6][7] This early chronology would largely place the Avestan period before the Achaemenid period, making it the earliest period of Iranian history for which literary sources are available.[8]

Sources

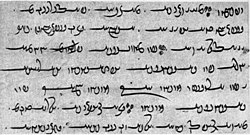

The primary source for the Avestan period are the texts of the Avesta, i.e., the collection of canonical texts of Zoroastrianism. All material in the Avesta is composed in Avestan, an otherwise unattested Old Iranian language. The Avesta itself was compiled and put into writing much later during the Middle Iranian Sassanian period by collecting texts used during Zoroastrian rituals.[9] At this time, Avestan had long ceased to be a spoken language and it is generally agreed that these texts had been passed down orally for some time.[10] The exact age and provenance of different Avestan texts are still debated, but scholars can reliably distinguish two linguistic layers, Old Avestan and Young Avestan.[11]

Old Avestan

The Old Avestan material consists of the Gathas, the Yasna Haptanghaiti, and a number of mantras, namely the Ashem Vohu, the Ahuna Vairya and the Airyaman ishya. These Old Avestan texts are assumed to have been composed close together and must have crystallized early on, possibly due to the associating with Zarathustra himself.[12] They all play a central role in the Yasna, the principal ritual of Zoroastrianism. A few texts are sometimes considered to be in pseudo Old Avestan, namely the Yenghe hatam mantra and some parts of the Yasna Haptanghaiti.[13] This could mean they originated during the Young Avestan period but were composed in such a way to make them appear more ancient.[14]

Young Avestan

The Young Avestan material is much larger, but also more varied and may reflect a longer time of composition and transmission, during which the different texts may have been constantly updated and revised.[15] At some time, however, this process stopped, i.e., the Young Avestan texts crystallized as well and the material was transmitted largely unchanged.[16] This could have happened during the Achaemenid period by Persian-speaking priests who no longer fully mastered the Avestan language.[17]

However, some Young Avestan texts are considered to have be revised or otherwise altered after the main parts of the corpus had already become fixed.[18] This may indicate a composition by people who didn't speak Avestan or after Avestan ceased to be a living language.[19][20] One example of such a late revision may be found in the extant Aban Yasht dedicated to Aredvi Sura Anahita. Anahita became popular under the Achaemenid kings, and some scholars have argued that certain verses in the Yasht may have been added later to reflect this rise in popularity and the Near Eastern influence that was exerted under royal patronage.[21] A particularly late date is often considered for the Vendidad, which is assumed to have been redacted by an editor or group of editors who compiled a number of early, now-lost Avestan sources, while having only a limited command of the Avestan language.[22] Apart from such changes and redactions, the extant Old and Young Avestan texts were then passed on orally for several centuries until they were eventually redacted and set down in writing during the Sassanid period, forming the Avesta as we have it today.[12]

Zoroastrian literature

In addition to the canonical texts in Avestan, Zoroastrianism features a large literature in Middle Persian. The most important of them are the Bundahishn, a collection of Zoroastrian cosmogony, and the Denkard, a form of encyclopedia of Zoroastrianism. These texts are not considered scripture but they do contain some additional material of the Avesta not contained in the extant text. This is due to the fact that a large portion of the Avesta became lost after the Islamic conquest of Iran and the subsequent marginalisation of Zoroastrianism.[23] The summaries and references made in the Middle Persian literature to these lost texts are therefore an additional source on the Avestan period.[24]

History

Geography

The Old Avestan parts of the Avesta contain no geographical places names that can be identified with any degree of certainty.[25][26] Later Iranian tradition identifies Airyanem Vaejah as the home of the early Iranians and birthplace of Zarathustra. However, there is no consensus on where Airyanem Vaijah may have been located or whether it was a real or mythological place.[27] Attempts to locate the Old Avestan society are therefore often contingent of the assumed chronology of the text. Proponents of an early chronology locate Zarathustra and his followers in Central Asia or Eastern Iran, whereas proponents of a late chronology sometimes place him in Western Iran.[28]

On the other hand, the Younger Avestan portion of the text contains a number of geographical references that can be identified with modern locations and therefore allow to delineate the geographical horizon of the Avestan people.[29] It is generally accepted that these place names are concentrated in the eastern parts of Greater Iran centered around the modern day countries of Afghanistan and Tajikistan.[30][31]

Chronology

There has been a long debate in modern scholarship about the chronology of the Avestan period, particularly about the life of Zarathustra as its most important event. While a relative chronology between the time of Zarathustra and that of his community in the Young Avestan period has been established with some certainty, opinions about its absolute place in time have changed considerably in recent decades. As far as the relative chronology is concerned, it is generally accepted that the Young Avestan period reflects considerable linguistic, social and cultural development compared to its Old Avestan predecessor.[32] Scholars therefore consider a time difference of several centuries necessary to explain these differences.[33] For example, Jean Kellens gives an estimate of roughly 400 years,[34] whereas Prods Oktor Skjaervo assumes that 300–500 years may separate Old and Young Avestan.[35]

- Approximate timeline of the Avestan period (estimates according to Prods Oktor Skjaervo[36]) vis-a-vis several regions inhabited by Indo-Iranian peoples from 1500 BCE to 0 CE. The range for the Old Avestan period represents an uncertainty range rather than a duration, i.e., Zarathustra and his immediate followers may have lived sometime during the indicated time frame.

As regards the absolute chronology, roughly two different approaches can be found in the literature; a late and an early chronology. The late chronology is based on a rather precise date for the life of Zarathustra placing him in the sixth century BCE. The Young Avestan period would therefore reflect the Hellenistic or even early Parthian period of Iranian history. This date appears in some Greek accounts of Zarathutra's life as well as in later Zoroastrian texts like the Bundahishn. The discussion around this chronology, therefore, strongly focused on the validity of these accounts, with scholars like Walter Bruno Henning, Ilya Gershevitch, and Gherardo Gnoli having made arguments in its favor whereas others have criticized them.[37][38]

The early chronology assumes a much earlier time frame for the Avestan period, with Zarathustra having lived sometime in the second half of second millennium BCE (1500-1000 BCE) and the Young Avestan period, therefore, reflecting the first half of the first millennium B.C.E. (1000 - 500 BCE).[36] This early chronology is sometimes supported by an older dating of Zarathustra's life which, while giving an implausibly early date of 6.000 year before Xerxes, suggest that the Greeks initially placed Zarathustra into a remote past.[39] In addition, two groups of arguments are typically made in favor of an early chronology. First, the numerous and strong parallels between Old Avestan and the early Vedic period, which itself is assumed to reflect the second half of second millennium BCE.[40] For example, both Old Avestan and the language of the Rigveda are still very close, suggesting only a limited time frame had passed since they split off from their common Proto-Indo-Iranian ancestor.[41] Furthermore, both depict a society of semi-nomadic pastoralists, make no mention of Iron, use chariots and engage in regular cattle raids.[42][43] Second, the Young Avestan texts lack any discernible Persian or Median influence indicating that the bulk of them was produced before the rise of the Achaemenid Empire.[44][45][46][47] As a result, much, in particular more recent, scholarship now supports an early chronology for the Avestan period.[48][49][50][51]

Archeology

Modern archaeology has unearthed a wealth of data on settlements and cultures in Central Asia and Greater Iran during the Avestan period, i.e., from the Middle Bronze Age to the rise of the Achaemenids.[52] However, linking these data to the literary sources of the Avesta remains difficult. This is due to the aforementioned uncertainty of the texts regarding when and where they were produced. As a result, any identification of a particular archaeological site or culture with parts of the Avesta runs the risk of circular reasoning.[53] Modern scholarship is, therefore, largely confined to interpret the material in the Avesta only within the broader outline of Iranian history, in particular the southward movement of Iranian tribes from the Eurasian steppe into southern Central Asia and eventually onto the Iranian plateau during the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age.[54]

Due to the pastoralism visible in the Old Avestan material, a connection with the Andronovo culture has been proposed for this period.[55] As regards the Young Avestan period, the region of southern Central Asia has attracted interest.[56] This is due to the shift from a pastoralist to a sedentary agricultural lifestyle, which is indicated for the time between the Old and Young Avestan period, and the interaction of the Avestan people with pastoralist steppe cultures, indicating a continued proximity to the steppe regions during the Young Avestan period.

During the Bronze Age, Southern Central Asia was home to a prominent urban civilization with long-range trade networks to the south. However, the middle of the second millennium BCE saw major transformations of this area, with the urban centers being replaced by smaller settlements and a shift to a mixed agricultural-pastoral economy with strong ties to the northern steppe regions.[57] This is commonly seen as a result of the migration of Iranian tribes from the steppe.[58] Within this context, one candidate for the Avestan society is the Tazabagyab culture in the region of Khwarazm.[59] This is sometimes connected to the location of Airyanem Vaejah, which Zoroastrian tradition names as the early homeland of the Iranians and birthplace of the Zoroastrian faith.[60] Another archeological culture that has attracted interest as a candidate for the Avestan society is the Yaz culture, also known as Sine-Sepulchro or Handmade-Painted-Ware cultural complex.[57] This is due to the fact that it is also connected to the southward spread of steppe-derived Iranian populations, the presence of farming practices consisted with the Young Avestan society and the lack of burial sites, indicating the Zoroastrian practice of Sky burial.[61]

Culture

Society

Old Avestan period

The Old Avestan texts reflect the perspective of a pastoralist society.[62] The cow is of primary importance and considered sacred.[63] In addition to cattle, livestock like sheep and goats are mentioned in the texts. Hippophoric names like Vishtaspa, Pourushaspa and Haecataspa (āspa, 'horse') show the value placed on horses. In addition, camelophoric names like Zarathustra and Frahaostra (uštra, 'camel') show the importance of the Bactrian camel, an animal well adapted to the harsh conditions of the steppe and desert regions of Central Asia.[64]

Kinship is perceived as concentric circles, with the innermost being the family (xvaētu), followed by the clan (vərəzə̄na) and the outermost being the tribe (airyaman).[65] These kinship groups may relate to geographical distinctions, with the family sharing a home (dəmāna), the clan living in a settlement (vīs), and the tribe living jointly in a land (dahyu).[66] There is a clear delineation between priest on one side and warrior-herdsmen on the other. However, it is not clear whether the later group is further separated like in the related Young Avestan and Vedic societies.[67] In the non-Zoroastrian Old Avestan society, priests are generally called karapan, whereas an officiating priest is called zaotar (compare Sanskrit: hotar) and mantras are uttered by priests called mąθran (compare Sanskrit: mántrin).[66]

There is no mention of horse riding but several allusion to chariots and chariot races are made. The Old Avestan people knew metal working. Like the Old Vedic term for metal ayas, the meaning of the Old Avestan term aiiah is unknown, but it has been interpreted as copper/bronze, consistent with a setting in the Bronze Age.[68][69]

Young Avestan period

The Young Avestan texts present a substantially different perspective. Society is now mostly sedentary and numerous references are being made to settlements and larger buildings.[70] Agriculture is very prominent and the texts name activities like ploughing, irrigating, seeding, harvesting and winnowing. Mentioned are grains like barley (yava) and wheat (gantuma). The Vendidad specifically states how "who sows grain sows Asha" and how it is equivalent to "ten thousand Yenghe hatam mantras". In addition, montane transhumance of cattle, sheep and goats is practiced and each September a feast similar to Almabtrieb (ayāθrima, driving in) is celebrated, after which the livestock is kept in stables during the winter.[71]

Young Avestan society has similar concentric circles of kinship; the family (nmāna), clan (vīs) and the tribe (zantu). Together with term for land (dahyu), they are related to the Old Avestan geographical distinctions. There is now a distinct tripartite division of the society into priests (Avestan: āθravan, Sanskrit: aθaravan, 'fire priest'), warriors (Avestan: raθaēštar, Sanskrit: raθešta, 'he who stands in a raθa'), and commoners (vāstryō.fšuyant, 'he who fattens cattle on pastures').[72] Despite the same division and the same general terms existing in the Vedic society, the specific names for priests, warriors and commoners are different, which may reflect an independent development of the two systems.[73] There is a single passage in the Avesta that names a fourth class, namely the craftsmen (huiti).[74]

Society appears to be very warlike and numerous references are made to battles with nomadic raiders.[75] The army is organised at the level of clans and tribes.[76] They march into battle with uplifted banners.[77] Chiefs ride chariots, while commoners fight on foot and warriors on horseback. Weapons include spears, maces and short swords. There is no mention of logistics, and military campaigns were probably only organised on a small scale.[76]

In the Young Avestan society, a number of features associated with Zoroastrianism, like the killing of noxious animals, purity laws, the veneration of the dog, and a strong dichotomy between good and evil, are already fully present.[73] Great emphasis is placed on procreation, and sexual activities that are not conducive to this goal, such as masturbation, homosexuality and prostitution, are strongly condemned.[78] One of the most salient elements of the Young Avestan society was the promotion of next-of-kin marriage (xᵛae.tuuadaθa), even between direct relatives. Although it is not clear to what extent it was practiced by common people, it has been speculated that this custom was part of an identity-building process in which the customs of closely related Indo-Iranian groups were deliberately inverted.[79]

Identity

The people of the Avesta consistently use the term Arya (Avestan: 𐬀𐬌𐬭𐬌𐬌𐬀, airiia) as a self designation. In Western Iran, the same term (Old Persian: 𐎠𐎼𐎡𐎹, ariyaʰ) appears in the 6th and 5th century BCE in several inscriptions by Darius and Xerxes. In those inscriptions, the use of the word Arya already indicates a sense of a wider, shared cultural space and modern scholars interpret Avestan and Old Persian Arya as the expressing of a distinct Iranian identity.[80][81] This identification of Arya with Iranian is, however, context specific.

On the one hand, the term Arya (Sanskrit: आर्य, ārya) also appears in ancient India as a self designation of the people of the Vedas. The people of the Avesta and of the Vedas share a wide range of linguistic, social, religious and cultural similarities and must have formed a single people at some earlier time.[82] Yet despite the close proximity of the Avestan and Vedic Arya, it is not clear if these two peoples had any continued interaction, since neither the Avesta nor the Vedas make any unambiguous reference to the other group.

On the other hand, the Avesta mentions a number of people with whom the Arya were in continuous contact with, namely the Turiia, Sairima, Sainu and Dahi. Despite the clear delineation between the Arya of the Avesta and these other groups, they all appear to be Iranian-speaking peoples.[83][84] The Turiia are the Turanians of later legends and said to live somewhere beyond the Oxus river. On the other hand, the Sairima and Dahi have been connected to the Sarmatians[85] and Dahae,[86] based on linguistic similarities, whereas the identity of the Sainu is unknown. Scholars, therefore, connect these peoples with the Iranian-speaking nomads that lived in the steppe zone of northern Central Asia.[87]

Religion

Zarathustra's religious reforms took place within the context of Old Iranian paganism. There are no direct sources on the religious beliefs of the Iranian peoples before Zarathustra, but scholars can draw on Zoroastrian polemics and use comparisons with the Vedic religion of Ancient India. There are a number of similarities between Zoroastrianism and the Vedic religion in the ritual sphere, suggesting they go back to the shared Indo-Iranian past.[88] The exact nature of Zarathustra's reforms remains a subject of debate among scholars, but the hostility experienced by the early Zoroastrian community suggests they were substantial.[89] A main target of Zarathustra's criticism was the Iranian cult of the Daevas.[90] These supernatural beings appear in the Vedic religion and later Hindusim as regular gods and it is assumed that they were once the gods of the Iranian peoples as well.[91]

Old Avestan period

Apart from his criticism of the Iranian Daeva cult, Zarathustra's reforms center around a supreme deity called Mazda (Avestan: 𐬨𐬀𐬰𐬛𐬃, the Wise One) or Ahura (Avestan: 𐬀𐬵𐬎𐬭𐬋, the Lord), as well as a fundamental opposition between good and evil. The teachings of Zarathustra, therefore, contain both monotheistic and dualistic elements.[92] There is no consensus on the origin of Mazda, who does not appear in the Vedic religion. Some scholars opine he may be a religious innovation of Zarathustra while others believe he represents an early Iranian innovation distinct from the Vedic tradition or that he is the Iranian counterpart of the Vedic Varuna.[93][94] The dualism expressed in the Gathas exist both within the contrast between Asha (Avestan: 𐬀𐬴𐬀, truth) and Druj (Avestan: 𐬛𐬭𐬎𐬘, deception) as well as between Vohu Manah (good mind) and Aka Manah (bad mind). While Asha and Druj have counterparts in Vedic Ṛta and Druh, both concepts have a more prominent and expanded role in Zarathustra's thinking.[95] The Gathas use the term Ahura for both Mazda and some supernatural entities associated with him.[96] Like the Deavas, the Ahuras have an equivalent in Ancient India as the Asuras. While during the Old Vedic period, both the Devas and Asuras are considered gods, the latter become demonized in the Late Vedic period, a process that parallels the demonization of the Daevas in Ancient Iran.

Young Avestan period

The religion expressed in the Young Avestan texts already exhibits the main elements associated with Zoroastrianism. [97] The dualism of the Old Avestan texts is now expressed in the divine sphere as the opposition between Ahura Mazda (the Wise Lord), whose name is now fixed, and Angra Mainyu (Avestan: 𐬀𐬢𐬭𐬀⸱𐬨𐬀𐬌𐬥𐬌𐬌𐬎, the Evil Spirit), who did not directly appear in the Gathas. The most striking difference, however, from the Old Avestan texts is the presence of a large number of deities called yazata (Avestan: 𐬫𐬀𐬰𐬀𐬙𐬀, one worthy of worship).[98] These deities add a pronounced polytheistic element to the religion.[99] Some of these deities have counterparts in the Vedic religion, whereas others may be Iranian innovations.[100] There is no consensus on how and why these deities appear in the Younger Avestan period. On the one hand, scholars like Mary Boyce believe this represents a continuation of Zarathustra's teaching. On the other hand, scholars such as Ilya Gershevitch have argued that Zoroastrianism is a syncretistic religion that formed from the fusion of Zarathustra's strictly dualistic teachings with the practices of polytheistic Iranian communities that were absorbed as the faith spread.[101]

World view

The people of the Avesta imagined the world to be divided into seven regions, the Haft Keshvar.[103] Six of these regions are placed in a concentric manner around the central one called xvaniraθa. This central continent is the home of the Avestan people. This is for instance expressed in the Mihr Yasht, which describes how Mithra is crossing Mount Hara and surveys the Airyoshayana, i.e., the lands inhabited by the Airiia, and the seven regions(Yt. 10.12-16, 67).[104] Mount Hara therefore stands at the center of the inhabited world. Around its peak, the Sun, the Moon and stars revolve, and the mythical river Aredvi Sura Anahita flows from its peak into the world ocean Vourukasha.

When the Iranians came into contact with the civilizations of the Ancient Near East, their geographical knowledge and perspective greatly increased. Consequently, their world view became influenced by the world view of these other peoples. For example, the Sassanians often used a fourfold division of the Earth, which was inspired by the Greeks. Regardless, the world view of the Avestan period remained common well into the Islamic period, where Iranian scholars like al-Biruni fused the knowledge of a spherical Earth with the Iranian concept of the seven regions.[105]

Epic tradition

In the Avesta, numerous allusions to the poetry, mythology, stories and folklore of the early Iranians can be found. In particular the Aban Yasht, the Drvasp Yasht, the Ram Yasht, the Den Yasht, and the Zamyad Yasht, often called the legendary Yashts, contain a large number of references.[106] The single largest source is, however, the Bundahishn, a compendium of Zoroastrian cosmogony from the Middle Ages written in Pahlavi.

The Avesta present a long history of the Iranians starting with the Pishdadian dynasty who is followed by the Kayanian dynasty. The last of the Kayanians is Vishtaspa, an early convert to Zoroastrianism and an important patron of Zarathustra. An important part of these stories is the fight between the Iranians (Airiia) against their archenemies the Turanians (Turiia). In particular, their king Franrasyan and his ultimately unsuccessful attempts to acquire the Khvarenah from them are described in great detail. Overall, these stories are considered primarily mythical. Characters like Yima, Thraetaona and Kauui Usan have counterparts in the Vedic Yama, Trita, and Kavya Ushanas and therefore must go back to the common Indo-Iranian period. Regardless, some elements may contain historical information. One example is a possible memory of the kinship between the Iranians peoples expressed through three sons of Thraetaona, namely Iraj (Airiia), Tur (Turiia) and Sarm (Sairima).[107][108] Another example is the historicity of the Kayanians. While early scholarship had largely accepted their historicity, more recent opinions range over a wide spectrum regarding this question.[109]

Elements of these stories and its characters occur prominently in many later Iranian texts like the Bahman-nameh, the Borzu Nama, the Darab-nama, the Kush Nama as well as most prominently in the Iranian national epic, the Shahnameh. The impact of the Avestan period on Iranian literary tradition was overall so substantial that Elton L. Daniel concluded "Its stories were so rich, detailed, coherent, and meaningful that they came to be accepted as records of actual events - so much so that they almost totally supplanted in collective memory the genuine history of ancient Iran."[110]

See also

- Avestan geography

- Vedic period, its Hindu counterpart

- Indo-Iranians

References

Notes

- ^ This dating of the Avestan period reflects the opinion of recent scholarship. For a more thoughrough discussion of the chronology and other possible datings, see below.

Citations

- ^ Daniel 2012, p. 51: "In addition to their religious thought, the Avestan people also contributed to another enduring aspect of Iranian culture, the epic tradition.".

- ^ Schmitt 2000, p. 25: "Die Sprachform der avestischen Texte insgesamt ist nicht einheitlich; es lassen sich zwei Hauptgruppen unterscheiden, die nicht nur chronologisch, sondern in einzelnen Punkten auch dialektologisch voneinander zu trennen sind[.]".

- ^ Skjaervø 1995, pp. 160-161: "There is therefore no reason to believe that the texts contained in the younger Avesta belong to even the same century".

- ^ Witzel 2000, p. 10: "Since the evidence of Young Avestan place names so clearly points to a more eastern location, the Avesta is again understood, nowadays, as an East Iranian text, whose area of composition comprised -- at least -- Sīstån/Arachosia, Herat, Merw and Bactria.".

- ^ Bryant 2001, p. 130: "Previously, a sixth century B.C.E. date based on Greek sources was accepted by many scholars, but this has now been completely discarded by present-day specialists in the field.".

- ^ Malandra 2009, "Controversy over Zaraθuštra's date has been an embarrassment of long standing to Zoroastrian studies. If anything approaching a consensus exists, it is that he lived ca. 1000 BCE give or take a century or so [...]".

- ^ Skjaervø 1995, p. 158 "In view of the dearth of historical sources it is of paramount importance that one should evaluate the evidence of the Avesta, the holy book of the Zoroastrians, parts at least of which antedate the Old Persian inscriptions by several centuries.".

- ^ de Vaan & Martínez García 2014, p. 3.

- ^ Hoffmann 1989, p. 90: "Mazdayasnische Priester, die die Avesta-Texte rezitieren konnten, müssen aber in die Persis gelangt sein. Denn es ist kein Avesta-Text außerhalb der südwestiranischen, d.h. persischen Überlieferung bekannt[...]. Wenn die Überführung der Avesta-Texte, wie wir annehmen, früh genug vonstatten ging, dann müssen diese Texte in zunehmendem Maße von nicht mehr muttersprachlich avestisch sprechenden Priestern tradiert worden sein".

- ^ Schmitt 2000, p. 25: "Die Sprachform der avestischen Texte insgesamt ist nicht einheitlich; es lassen sich zwei Hauptgruppen unterscheiden, die nicht nur chronologisch, sondern in einzelnen Punkten auch dialektologisch voneinander zu trennen sind".

- ^ a b Skjaervø 2009, p. 46.

- ^ Hoffmann 1996, p. 34: "Doch sind einige zusammenhängende jav. Textstücke vor allem durch die Durchführung auslautender Langvokale (§5,2) dem Aav. oberflächlich angeglichen; man kann die Sprache dieser Stücke pseudo-altavestisch (=pseudo-aav) nennen.".

- ^ Humbach 1991, p. 7.

- ^ Hintze 2014, "Like other parts of the Avesta, including Young Avestan sections of the Yasna, Visperad, Vidēvdād, and Khorde Avesta, the Yašts were produced throughout the Old Iranian period in the oral culture of priestly composition, which was alive and productive as long as the priests were able to master the Avestan language.".

- ^ de Vaan & Martínez García 2014.

- ^ Skjaervø 2011, p. 59: "The Old Avestan texts were crystallized, perhaps, some time in the late second millennium BCE, while the Young Avestan texts, including the already crystallized Old Avesta, were themselves, perhaps, crystallized under the Acheamenids, when Zoroastrianism became the religion of the kings".

- ^ Skjaervø 1995, p. 163: "Finally, some parts of the Young Avesta, in particular of the Videvdad, exhibit grammatical features very similar to those of late Old Persian, that is, texts consisting of "correct words with the wrong grammatical ending"".

- ^ Skjaervø 1995, p. 166.

- ^ Schmitt 2000, p. 26: "Andere Texte sind von sehr viel geringerem Rang und zeigen eine sehr uneinheitliche und oft grammatisch fehlerhafte Sprache, die deutlich verrät, daß die Textverfasser oder -kompilatoren sie gar nicht mehr verstanden haben".

- ^ Boyce 2014, "[T]here are others which appear to have been composed after the syncretistic identification of Arədvī Sūrā with the Semitic goddess Anaïtis. [...] The final version is linguistically harmonious; but the literary quality varies greatly, from some truly poetic lines in the archaic portions to the halting Avestan of the latest additions".

- ^ Hoffmann 1996, p. 36: "Nach dem Sturz der Sassaniden durch die islamische Eroberung (651 n. Chr.) kam über das Avesta eine Zeit des Niedergangs. In dieser "Nachsasanidischen Verfallszeit" gingen große Teile des Avesta verloren".

- ^ Boyce 1990, p. 4:"Several important Pahlavi books consist largely or in part of selections from the Zand of lost Avestan nasks, often cited by name; and by comparing these with the Zand of extant texts it becomes possible to distinguish fairly confidently the translation from the paraphrases and commentaries, and so to attain knowledge of missing doctrinal and narrative Avestan works".

- ^ Boyce 1996, p. 250: "The Fravasis are also honoured of individuals in the lands of Muzii, Raozdyii, Tanya, Auhvi and ApakhSirii. As has been said: "We suffer the torments of Tantalus with regard to these names, whose secret will probably always elude us". One can only presume that they belonged to regions in the remote north-east, at some distant time in the prehistory of that area".

- ^ Grenet 2015, p. 21: "Does the Avesta contain any reliable evidence concerning the place where the "real" Zarathustra (i.e., the person repeatedly mentioned in the Gāthās) lived? The answer is no".

- ^ Vogelsang 2000, pp. 49: "An additional problem is the question whether all the lands that are mentioned in the list refer to an actual geographical location, or whether in at least some cases we are dealing with mythical names that bear no direct relationship to a specific area. Such a point has often been brought forward as regards the first and the last names in the list: Airyanem Vaejah (No. 1) and Upa Aodaeshu Rahnghaya (No. 16)".

- ^ Grenet 2015, pp. 22-24.

- ^ Grenet 2015, p. 21: "Can we determine the regional and, to a certain extent, the archaeological context where his followers lived a few centuries later, before they entered recorded history? The answer is definitely yes".

- ^ Witzel 2000, p. 48: "The Vīdẽvdaδ list obviously was composed or redacted by someone who regarded Afghanistan and the lands surrounding it as the home of all Aryans (airiia), that is of all (eastern) Iranians, with Airiianem Vaẽjah as their center".

- ^ Vogelsang 2000, p. 58: "The list describes the lands which are located to the north, west, south and east of the mountains of modern Afghanistan".

- ^ Daniel 2012, p. 46: "The society of the Avestan people was in many respects a simple one, but it changed considerably in the period from Old Avestan to Young Avestan times.".

- ^ Hintze 2015, p. 38: "Linguistic, literary and conceptual characteristics suggest that the Old(er) Avesta pre‐dates the Young(er) Avesta by several centuries.".

- ^ Kellens 1989, p. 36.

- ^ Skjaervø 1995, p. 162.

- ^ a b Skjaervø 2012, p. 2.

- ^ Shahbazi 1977, pp. 25-35.

- ^ Stausberg 2008, p. 572.

- ^ Boyce 1996, p. 191: "The prophet himself must therefore have flourished centuries earlier, and this accords with the fact that the Greeks in the 6th century learnt of him from the Persians as a figure belonging to immense, remote antiquity.".

- ^ Bryant 2001, p. 130: "The oldest parts of the Avesta, which is the body of texts preserving the ancient canon of the Iranian Zarthustrian tradition, is linguistically and culturally very close to the material preserved in the Rgveda.".

- ^ Humbach 1991, p. 73: "Though phonetically somewhat dissimilar from each other, Old Avestan (in its original form) and Vedic had not yet developed far from each other.".

- ^ Boyce 1996, p. 14: "there is not a single simile there drawn from tilling the soil - no mention of plough or com, seed time or harvest, though such things are much spoken of in the Younger Avesta.".

- ^ Schwartz 1985, p. 662: "It is a striking fact that in the oldest Avestan texts, the Gathas, which abound, as we have seen, in cattle imagery, there seems to be little or no reference to agriculture.".

- ^ Skjaervø 1995, p.166 "The fact that the oldest Young Avestan texts apparently contain no reference to western Iran, including Media, would seem to indicate that they were composed in eastern Iran before the Median domination reached the area.".

- ^ Boyce 1996, p. 191: "Had it been otherwise, and had Zoroastrianism been carried in its infancy to the Medes and Persians, these imperial people must inevitable have found mention in its religious works.".

- ^ Vogelsang 2000, p. 62 "All of the above observations would indicate a date for the composition of the Videvdat list which would antedate, for a considerable time, the arrival in Eastern Iran of the Persian Acheamenids (ca. 550 B.C.)".

- ^ Grenet 2005, pp. 44-45 "It is difficult to imagine that the text was composed anywhere other than in South Afghanistan and later than the middle of the 6th century BCE.".

- ^ Stausberg 2002, p. 27 "Die 'Spätdatierung' wird auch in der jüngeren Forschung gelegentlich vertreten. Die Mehrzahl der Forscher neigt heutzutage allerding der 'Frühdatierung' zu".

- ^ Kellens 2011, pp. 35-44 "In the last ten years a general consensus has gradually emerged in favor of placing the Gāthās around 1000 BCE [...]".

- ^ Daniel 2012, p. 47: "Recent research, however, has cast considerable doubt on this dating and geographical setting. [...] All in all, it seems likely that Zoroaster and the Avestan people flourished in eastern Iran at a much earlier date (anywhere from 1500 to 900 B.C.) than once thought.".

- ^ Lhuillier & Boroffka 2018.

- ^ Skjaervø 1995, p. 158: "Of course, when we use archaeology and history to date the Avesta, we cannot turn around and use the Avesta to date the same archaeological and historical events, and vice versa.".

- ^ Hintze 2015, p. 38: " Although it is currently not possible to correlate archaeological and linguistic evidence, the most likely model historically is that Iranian tribes were on the move southwards into Iran some time around the mid‐2nd millennium bce. The provenance of the Avesta and of the Zoroastrian religion would then coincide with that of the Avestan language and early Iranians, presumably in the area of Southern Central Asia.".

- ^ Grenet 2015, p. 22: "All things considered, our chronological and cultural parameters tend to suggest locating Zarathustra (or, at least, the "Gathic community") in the northern steppes in the Bronze Age period, prior to the southward migration of the Iranian tribes, thus favoring some variant of the Andronovo pastoralist culture of present‐day Kazakhstan around c. 1500–1200 BCE.".

- ^ Kuzmina 2008, chap. Archeological Cultures of Southern Central Asia.

- ^ a b Lhuillier 2019.

- ^ Kuzmina 2007.

- ^ Boyce 1996, pp. 3-4: "The linguistic evidence shows, moreover, that his home must have been among the Iranians of the north-east; and it is probable that his own people (known as the "Avestan people" from the name of the Zoroastrian scriptures, the Avesta) settled eventually in Khwarezmia, the land along the lower course of the Oxus.".

- ^ Vogelsang 2000, p. 9: "The land of Airyanem Vaejah, which is described in the text as a land of extreme cold, has often been identified with ancient Choresmia.".

- ^ Kuzmina 2007, p. 430.

- ^ Daniel 2012, p. 46: "There is no indication that urban life or trade and commerce were of any importance in the Old Avestan period.".

- ^ Daniel 2012, p. 47: "The economy was primarily based on the herding of livestock; the people were pastoralists, cattle served as the basic unit of economic exchange, and the cow was venerated as sacred.".

- ^ Schmitt 1979, pp. 337–348.

- ^ Skjaervø 1995, p. 167.

- ^ a b Boyce 2011, p. 63.

- ^ Skjaervø 1995, p. 168: "The original meaning of this word may have been "bronze," but its exact meaning in the Gathas cannot be determined.".

- ^ Witzel 1995, "The next major archaeological date available is that of the introduction of iron at c. 1200 B.C. It is first mentioned in the second oldest text, the Atharvaveda, as 'black metal' (krsna ayas, ́syama ayas) while the Rigveda only knows of ayas itself "copper/bronze".".

- ^ Skjaervø 1995, p. 169: "Architectural imagery play an important role: colums supporting "towering" buildings, beams, porches, and so on, are a clear indication of a settled society.".

- ^ Schwartz 1985, pp. 658-663.

- ^ Schwartz 1985, pp. 650-651.

- ^ a b Boyce 2011, p. 66.

- ^ Schwartz 1985, p. 651.

- ^ Boyce 2011, p. 65: "During the course of these events the more warlike "Younger Avestan" society evolved.".

- ^ a b Shahbazi 2011, p. 489.

- ^ Schwartz 1985, p. 654.

- ^ Daniel 2012, "Interestingly, many customs of the Avestan people seem to have been almost deliberately designed to reinforce a sense of identity as a people apart from the non-Aranys and even other Aryans".

- ^ Kellens 2005, pp. 233-251.

- ^ Gnoli 2006, p. 504: "The inscriptions of Darius I [...] and Xerxes, in which the different provinces of the empire are listed, make it clear that, between the end of the 6th century and the middle of the 5th century B.C.E., the Persians were already aware of belonging to the ariya "Iranian" nation".

- ^ Bailey 2011, pp. 681-683.

- ^ Boyce 1996, p. 104: "In the Farvadin Yasht, 143-4, five divisions are recognized among the Iranians, namely the Airya (a term which the Avestan people appear to use of themselves), Tuirya, Sairima, Sainu and Dahi".

- ^ Schwartz 1985, p. 648: "While it is obvious that Iranian dialects were spoken throughout the East, and, as we have seen, a vast ares is regarded by the Avesta as Aryan, we find individuals bearing Iranian names who are classed as belonging to peoples others than Iranian (Airyas).".

- ^ Bailey 2011, p. 65: "In the Scythian field there are two names to be mentioned. The Sarmatai are in the Avesta Sairima-, and there are also the Sauromatai. The etyma of these two names are somewhat complex. The Sarmatai survived in the Zor. Pahl. slm *salm (the -l- is marked for -l-, not -r-, Bundashin TD 2, 106.15).".

- ^ Bailey 1959, p. 109: "A people called by the ethnic name Iran. daha-, now found in Old Persian daha placed before saka in an inscription of Xerxes (Persopolis h 26) has long been known. The Akkadian form is da-a-an for *daha-. The Avestan *daha- attested in the fem. dahi;- is an epithet of lands. Yasht 13.143-4 has the list airyanam ... tūiryanam ... sairimanam ... saininam ... dahinam ... From this we get : Arya-, Turiya-, Sarima-, Saini-, Daha-, as names of peoples known to the early litany of Yasht 13.".

- ^ Daniel 2012, p. 52: "They also included tales of the Kayanian kings, culminating in the reign of Kavi Vishtaspa (Goshtasp) and the warfare between the Iranians and their natural enemies, the Turanians (probably nomadic peoples to the north of Iran, later identified with the Turks).".

- ^ Gnoli 2012, "The highly ritualistic nature of the Vedic religion and of the religious world in which, by way of reaction and deliberate opposition, Zoroaster's message established itself, features a number of common points.".

- ^ Foltz 2013, p. 61: "Apparently Zoroaster's ideas were often seen as a threat, since there are hints, in the Avesta and elsewhere, of his missionaries being persecuted and even killed.".

- ^ Ahmadi 2019.

- ^ Herrenschmidt 2011, " That they were national gods is confirmed by the fact that they were invoked by means of the Iranian versions of expressions common in Vedic rhetoric, for example, daēuua-/maṧiia-: devá-/mártya-, vīspa-daēuua-: víśva- devá-, and daēuuo.zušta-: devájuṣṭa-.".

- ^ Boyd & Crosby 1979.

- ^ Hintze 2015, p. 33.

- ^ Kuiper 1976.

- ^ Stausberg 2002, p. 95.

- ^ Skjaervø 2012, p. 12: "In the Old Avesta, divine beings are referred to as "lords" (ahura, Old Indic asura), among them the heavenly fire, Ahura Mazdā's son, but they are mostly anonymous.".

- ^ Skjaervø 1995, p. 169: "In religion, for the first time, we find allusions to the cosmological myth well known from later times: the stages of the creation of Ahura Mazda; the attack of the aggressor, Agra Mainiiu and his coming through the division between the world of light and that of darkness. [...] We also have for the first time a description of the end of time, when Astuuat.areta will rise out of Lake Kasaoiia to banish the lie from the world of order ( Yt 19).".

- ^ Skjaervø 2012, p. 12: "The Young Avestan term for "deity, god" is yazata, literally "worthy of sacrifices" (only male deities), which is an epithet of Ahura Mazdā in the Old Avesta (Yasna 41.3).".

- ^ Hintze 2013.

- ^ Skjaervø 1995, p. 169: "Numerous deities are invoked or simply mentioned, most of whom are inherited, but some only of Iranian date, such as the goddesses Ashi and Druuäspä, both of whom were worshipped in central Asia during the Kushan period (Duchesne-Guillemin 1962: 240).".

- ^ Gershevitch 1967, pp. 13-14.

- ^ Gershevitch 1967.

- ^ Boyce 1990, pp. 16-17.

- ^ Gershevitch 1967, pp. 79-80.

- ^ Shahbazi 2012, pp. 519-522: "In due course and under the influence of astronomers, the seven climes came to be pictured as seven tracts of land above and parallel to the equator, each belonging to a planet and associated with one or two signs of the zodiac.".

- ^ Hintze 2014.

- ^ Boyce 1996, pp. 104–105: "The eponymous founders of the second and third groups figure with "Airya" in the Pahlavi tradition as Erec (older *Airyaeca), Tuc (*Tur(a)ca) and Sarm, who are represented as the three sons of Faredon among whom he divided the world. In the Book of Kings they appear as :Eraj, Tur and Salm, of whom Eraj received the realm of Iran itself, Tur the lands to north and east, and Salm those to the west; and ultimately the people of Tur, the Turanians, were identified with the alien Turks, who came to replace the Iranians in those lands."

- ^ Kuzmina 2007, p. 174 "In Iranian texts, the idea about the kinship of all Iranian-speaking languages is reflected in a legend of how the ancestor of the Iranians divided the land between three sons: Sairima, the forefather of Sauromatians (who dwelt in the historic period from the Don to the Urals), Tur, from whom the Turians originated (the northern part of Central Asia was called Turan), and the younger son Iraj, the ancestor of the Iranian population (Christensen 1934).".

- ^ Skjaervø 2013.

- ^ Daniel 2012, p. 47.

Bibliography

- Ahmadi, Amir (2019). The Daeva Cult in the Gathas: An Ideological Archaeology of Zoroastrianism. Iranian Studies. Vol. 24. Routledge. ISBN 978-0367871833.

- Bailey, Harold W. (1959). "Iranian Arya and Daha". Transactions of the Philological Society. 58: 71–115. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.1959.tb00300.x.

- Bailey, Harold W. (2011). "Arya". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II. Iranica Foundation.

- Boyce, Mary (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism (Textual Sources for the Study of Religion). The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226069302.

- Boyce, Mary (1996). A History Of Zoroastrianism: The Early Period. Brill.

- Boyce, Mary (2014). "Ābān Yašt". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. I. Iranica Foundation. pp. 60–61.

- Boyce, Mary (2011). "Avestan People". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III. Iranica Foundation. pp. 62–66.

- Boyd, James W.; Crosby, Donald A. (1979). "Is Zoroastrianism Dualistic or Monotheistic?". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 47 (4): 557–588. doi:10.1093/jaarel/XLVII.4.557. JSTOR 1462275 – via JSTOR.

- Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 131.

- Daniel, Elton L. (2012). The History of Iran. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0313375095.

- Foltz, Richard C. (2013). Religions of Iran: From Prehistory to the Present. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 978-1780743080.

- Geiger, Wilhelm (1884). "Vaterland und Zeitalter des Awestā und seiner Kultur". Sitzungsberichte der königlichen bayrischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. 2: 315–385.

- Gershevitch, Ilya (1967). The Avestan Hymn to Mithra. Cambridge University Press.

- Gershevitch, Ilya (1968). "Old Iranian Literature". In Spuler, B. (ed.). Handbuch der Orientalistik. Brill. pp. 1–32. doi:10.1163/9789004304994_001. ISBN 9789004304994.

- Gnoli, Gherardo (1980). Zoroaster's Time and Homeland: A Study on the Origins of Mazdeism and Related Problems. Istituto universitario orientale.

- Gnoli, Gherardo (2012). "Indo-Iranian Religion". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XIII. Iranica Foundation. pp. 97–100.

- Gnoli, Gherardo (2006). "Iranian Identity ii. Pre-Islamic Period". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XIII. Iranica Foundation. pp. 504–507.

- Grenet, Frantz (2005). "An Archaeologist's Approach to Avestan Geography". In Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Stewart, Sarah (eds.). Birth of the Persian Empire Volume I. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-7556-2459-1.

- Grenet, Frantz (2015). "Zarathustra's Time and Homeland - Geographical Perspectives". In Stausberg, Michael; Vevaina, Yuhan S.-D.; Tessmann, Anna (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 9781118785539.

- Herrenschmidt, Clarisse (2011). "Daiva". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. VI. Iranica Foundation. pp. 599–602.

- Hintze, Almut (2013). "Monotheism the Zoroastrian Way". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 24 (2): 225–249. JSTOR 43307294 – via JSTOR.

- Hintze, Almut (2014). "Yašts". Encyclopædia Iranica. Iranica Foundation.

- Hintze, Almut (2015). "Zarathustra's Time and Homeland - Linguistic Perspectives". In Stausberg, Michael; Vevaina, Yuhan S.-D.; Tessmann, Anna (eds.). The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Zoroastrianism. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 9781118785539.

- Hoffmann, Karl (1996). Avestische Laut- und Flexionslehre (in German). Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck.

- Hoffmann, Karl (1989). Der Sasanidische Archetypus - Untersuchungen zu Schreibung und Lautgestalt des Avestischen (in German). Reichert Verlag. ISBN 9783882264708.

- Homayoun, Nasser T. (2004). Kharazm: What do I know about Iran?. Cultural Research Bureau. ISBN 964-379-023-1.

- Humbach, Helmut (1991). The Gathas of Zarathustra and the Other Old Avestan Texts. Carl Winter Universitätsverlag.

- Kellens, Jean (1989). "Avestique". In Schmitt, Rüdiger (ed.). Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum. Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag.

- Kellens, Jean (2011). "Avesta i. Survey of the history and contents of the book". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. III. Iranica Foundation.

- Kellens, Jean (2005). "Les Airiia - ne sont plus des Āryas: ce sont déjà des Iraniens". Āryas, Aryens et Iraniens en Asie centrale. Association de Boccard.

- Kuiper, F. B. J. (1976). "Ahura "Mazda" 'Lord Wisdom'?". Indo-Iranian Journal. 18 (1–2): 25–42. doi:10.1163/000000076790079465. JSTOR 24652589 – via JSTOR.

- Kuzmina, Elena E. (2007). J.P. Mallory (ed.). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-2071-2.

- Kuzmina, Elena E. (2008). Victor H. Mair (ed.). The Prehistory of the Silk Road (Encounters With Asia). University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0812240412.

- Lhuillier, Johanna; Boroffka, Nikolaus, eds. (2018). A Millennium of History: The Iron Age in southern Central Asia (2nd and 1st Millennia BC)Proceedings of the conference held in Berlin (2014). Archäologie in Iran und Turan, Band 17. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-496-01594-9.

- Lhuillier, Johanna (2019). "The Settlement Pattern in Central Asia during the Early Iron Age". Urban Cultures of Central Asia from the Bronze Age to the Karakhanids: Learnings and conclusions from new archaeological investigations and discoveries. Proceedings of the First International Congress on Central Asian Archaeology held at the University of Bern (1st ed.). Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 115–128. doi:10.2307/j.ctvrnfq57.12. ISBN 9783447111690. JSTOR j.ctvrnfq57.12.

- Malandra, William W. (2006). "Vendīdād i. Survey of the history and contents of the text". Encyclopædia Iranica. Iranica Foundation.

- Malandra, William W. (2009). "Zoroaster ii. General Survey". Encyclopædia Iranica. Iranica Foundation.

- Malandra, William W. (2018). The Frawardin Yašt: Introduction, Translation, Text, Commentary, Glossary. Ancient Iran. Vol. 8. Brill Academic Pub. ISBN 978-1949743036.

- Skjaervø, P. Oktor (1995). "The Avesta as source for the early history of the Iranians". In Erdosy, George (ed.). The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia. De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110144475.

- Skjaervø, P. Oktor (2011). "Avestan Society". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199390427.

- Skjaervø, P. Oktor (2013). "Kayāniān xiv. The Kayanids in Western Historiography". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II. Iranica Foundation.

- Skjaervø, P. Oktor (2009). "Old Iranian". In Windfuhr, Gernot (ed.). The Iranian Languages. Routledge. ISBN 9780203641736.

- Skjaervø, P. Oktor (2012). The Spirit of Zoroastrianism. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17035-1.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2000). "Die Sprachen der altiranischen Periode". Die iranischen Sprachen in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag Wiesbaden. ISBN 3895001503.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (1979). "Die avestischen Namen". Iranisches Personennamenbuch, Band I: Die altiranischen Namen. Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. ISBN 978-3-7001-0300-4.

- Schwartz, Martin (1985). "The Old Eastern Iranian World View According to the Avesta". In Gershevitch, I. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 2: The Median and Achaemenian Periods. Cambridge University Press. pp. 640–663. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521200912.014. ISBN 9781139054935.

- Shahbazi, Alireza Shapur (1977). "The 'Traditional Date of Zoroaster' Explained". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 40 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00040386. JSTOR 615820. S2CID 161582719.

- Shahbazi, Alireza Shapur (2012). "Haft Kešvar". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. XI. Iranica Foundation.

- Shahbazi, Alireza Shapur (2011). "Army i. Pre-Islamic Iran". Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II. Iranica Foundation.

- Stausberg, Michael (2008). "On the State and Prospects of the Study of Zoroastrianism". Numen. 55 (5): 561–600. doi:10.1163/156852708X310536. S2CID 143903349.

- Stausberg, Michael (2002). Die Religion Zarathushtras: Geschichte - Gegenwart - Rituale. Vol. 1 (1st ed.). W. Kohlhammer GmbH. ISBN 978-3170171183.

- de Vaan, Michiel; Martínez García, Javier (2014). Introduction to Avestan (PDF). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-25777-1.

- Vogelsang, Willem (2000). "The sixteen lands of Videvdat - Airyanem Vaejah and the homeland of the Iranians". Persica. 16. doi:10.2143/PERS.16.0.511.

- Witzel, Michael (2000). "The Home of the Aryans". In Hinze, A.; Tichy, E. (eds.). Festschrift für Johanna Narten zum 70. Geburtstag (PDF). J. H. Roell. pp. 283–338. doi:10.11588/xarep.00000114.

- Witzel, Michael (1995). "Early Sanskritization Origins and Development of the Kuru State". Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies. 1 (4): 1–27. doi:10.11588/ejvs.1995.4.823.