Ben Nevis

| Ben Nevis | |

|---|---|

| Beinn Nibheis | |

Ben Nevis from Banavie. The summit is beyond and to the left of the apparent highest point. | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,345 m (4,413 ft)[1] |

| Prominence | 1,345 m (4,413 ft) Ranked 1st in British Isles |

| Parent peak | none – Highest peak on island of Great Britain |

| Isolation | 739 km (459 mi) |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 56°47′49″N 5°00′13″W / 56.79685°N 5.003508°W |

| Geography | |

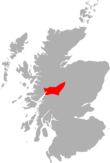

| Location | Lochaber, Highland, Scotland |

| Parent range | Grampian Mountains |

| OS grid | NN166712 |

| Topo map | OS Landranger 41, Explorer 392 |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 19 August 1771, by James Robertson[2] |

| Easiest route | Pony track and mountain path |

Ben Nevis (/ˈnɛvɪs/ NEV-iss; Template:Lang-gd, Scottish Gaelic pronunciation: [pe(ɲ) ˈɲivɪʃ]) is the highest mountain in Scotland, the United Kingdom and the British Isles. The summit is 4,411 feet (1,345 m)[1] above sea level and is the highest land in any direction for 459 miles (739 kilometres).[3][a] Ben Nevis stands at the western end of the Grampian Mountains in the Highland region of Lochaber, close to the town of Fort William.

The mountain is a popular destination, attracting an estimated 130,000 ascents a year,[4] around three-quarters of which use the Mountain Track from Glen Nevis.[5] The 700-metre (2,300 ft) cliffs of the north face are among the highest in Scotland, providing classic scrambles and rock climbs of all difficulties for climbers and mountaineers. They are also the principal locations in Scotland for ice climbing.

The summit, which is the collapsed dome of an ancient volcano,[6] features the ruins of an observatory which was continuously staffed between 1883 and 1904. The meteorological data collected during this period is still important for understanding Scottish mountain weather. C. T. R. Wilson was inspired to invent the cloud chamber after a period spent working at the observatory.

Etymology

Ben Nevis is the Anglicisation of the Scottish Gaelic name Beinn Nibheis. Whilst Beinn is the common Scottish Gaelic word for 'mountain', the meaning of Nibheis is unclear.

Nibheis may preserve an earlier Pictish form, *Nebestis or *Nebesta, involving the Celtic root *neb, meaning 'clouds' (compare: Welsh nef ).,[7] thus 'Cloudy Mountain'.

Nibheis may also have an origin with the words nèamh meaning 'heaven' (which is related to the modern Scottish Gaelic word neamh meaning 'bright, shining') and bathais meaning 'the top of a man's head'. Thus, Beinn Nibheis could derive from beinn nèamh-bhathais, "the mountain with its head in the clouds",[8] or 'mountain of heaven'.[9]

Alternatively, the Scottish Gaelic word neimh can be translated as 'malice', 'poison' or 'venom'[9] giving 'venomous mountain', possibly describing the storms that envelop the summit.

Nibheis, can also be the genitive form of a male (god's?) name. This could be the god Lugh whose place of worship was often on mountain tops throughout the Celtic world, thus giving 'god's mountain'. [citation needed]

As is common for many Scottish mountains, it is known both to locals and visitors as simply the Ben.[10][11]

Geography

Ben Nevis forms a massif with its neighbours to the northeast, Càrn Mòr Dearg, to which it is linked by the Càrn Mòr Dearg Arête, Aonach Beag and Aonach Mòr.[12] All four are Munros and among the eleven mountains in Scotland over 4,000 feet (1,200 m) (of which nine are currently listed as Munros).

The western and southern flanks of Ben Nevis rise 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) in about 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) above the River Nevis flowing down Glen Nevis – the longest and steepest hill slope in Britain[8] – with the result that the mountain presents an aspect of massive bulk on this side. To the north, by contrast, cliffs drop some 600 metres (2,000 ft) to Coire Leis (IPA: [ˈkʰɔɾʲə ˈleʃ]).

A descent of 200 metres from this corrie leads to the Charles Inglis Clark Memorial Hut (known as the CIC Hut), a private mountain hut 680 metres (2,230 ft) above sea level, owned by the Scottish Mountaineering Club[13] and used as a base for the many climbing routes on the mountain's north face. The hut is just above the confluence of Allt a' Mhuilinn and Allt Coire na Ciste.

In addition to the main 1,345-metre (4,413 ft) summit, Ben Nevis has two subsidiary "tops" listed in Munro's Tables, both of which are called Càrn Dearg ("red hill").[14] The higher of these, at 1,221 metres (4,006 ft), is to the northwest, and is often mistaken for Ben Nevis itself in views from the Fort William area. The other Càrn Dearg (1,020 m (3,350 ft)) juts out into Glen Nevis on the mountain's southwestern side. A lower hill, Meall an t-Suidhe (711 metres (2,333 ft)), is further west, forming a saddle with Ben Nevis which contains a small loch, Lochan Meall an t-Suidhe. The popular tourist path from Glen Nevis skirts the side of this hill before ascending Ben Nevis's broad western flank.

Geology

Ben Nevis is all that remains of a Devonian volcano that met a cataclysmic end in the Carboniferous period around 350 million years ago. Evidence near the summit shows light-coloured granite (which had cooled in subterranean chambers several kilometres beneath the surface) lies among dark basaltic lavas (that form only on the surface). The two lying side by side is evidence the huge volcano collapsed in on itself creating an explosion comparable to Thera (2nd millennium BC) or Krakatoa (1883).[6] The mountain is now all that remains of the imploded inner dome of the volcano.[15] Its form has been extensively shaped by glaciation.[16]

Research has shown igneous rock from the Devonian period (around 400 million years ago) intrudes into the surrounding metamorphic schists; the intrusions take the form of a series of concentric ring dikes. The innermost of these, known as the Inner Granite, constitutes the southern bulk of the mountain above Lochan Meall an t-Suidhe, and also the neighbouring ridge of Càrn Mòr Dearg; Meall an t-Suidhe forms part of the Outer Granite, which is redder in colour. The summit dome itself, together with the steep northern cliffs, is composed of andesite and basaltic lavas.[17][18]

Climate

Ben Nevis has a highland tundra climate (ET in the Köppen classification). Ben Nevis's elevation, maritime location and topography frequently lead to cool and cloudy weather conditions, which can pose a danger to ill-equipped walkers. According to the observations carried out at the summit observatory from 1883 to 1904, fog was present on the summit for almost 80% of the time between November and January, and 55% of the time in May and June.[19] The average winter temperature was around −5 °C (23 °F),[19] and the mean monthly temperature for the year was −0.5 °C (31.1 °F).[20] In an average year the summit sees 261 gales,[20] and receives 4,350 millimetres (171 in) of rainfall, compared to only 2,050 millimetres (81 in) in nearby Fort William,[21] 840 millimetres (33 in) in Inverness and 580 millimetres (23 in) in London. Rainfall on Ben Nevis is about twice as high in the winter as it is in the spring and summer. Snow can be found on the mountain almost all year round, particularly in the gullies of the north face – with the higher reaches of Observatory Gully holding snow until September most years and sometimes until the new snows of the following season.

| Climate data for Ben Nevis (1883-1904) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 9.1 (48.4) |

7.8 (46.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.4 (52.5) |

13.3 (55.9) |

19.1 (66.4) |

17.8 (64.0) |

17.5 (63.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

19.1 (66.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −2.5 (27.5) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

2.6 (36.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

6.4 (43.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

1.4 (34.5) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−1.9 (28.6) |

1.6 (34.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −4.4 (24.0) |

−4.6 (23.8) |

−4.4 (24.0) |

−2.4 (27.6) |

0.6 (33.0) |

4.3 (39.7) |

5.1 (41.1) |

4.7 (40.4) |

3.3 (38.0) |

−0.3 (31.4) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−0.3 (31.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −6.2 (20.8) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

2.1 (35.8) |

3.1 (37.6) |

2.9 (37.2) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−5.5 (22.1) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.4 (0.7) |

−16.8 (1.8) |

−15.8 (3.6) |

−11.5 (11.3) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−12.1 (10.2) |

−13.8 (7.2) |

−17.4 (0.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 469.8 (18.50) |

342.0 (13.46) |

378.9 (14.92) |

237.2 (9.34) |

204.4 (8.05) |

193.7 (7.63) |

269.8 (10.62) |

331.3 (13.04) |

391.6 (15.42) |

397.8 (15.66) |

394.8 (15.54) |

492.3 (19.38) |

4,103.8 (161.57) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 22.4 | 16.8 | 20.1 | 16.5 | 17.0 | 16.1 | 21.0 | 22.0 | 20.0 | 21.9 | 20.4 | 21.3 | 235.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 22.4 | 42.3 | 54.7 | 80.4 | 116.3 | 127.0 | 84.8 | 58.1 | 62.3 | 41.8 | 27.8 | 18.0 | 735.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 10 | 16 | 15 | 19 | 23 | 22 | 16 | 13 | 16 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 16 |

| Source 1: CEDA Archive[22] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Royal Society of Edinburgh (mean temp and sunshine 1884-1903)[23] | |||||||||||||

History

The first recorded ascent of Ben Nevis was made on 17 August 1771[24] by James Robertson, an Edinburgh botanist, who was in the region to collect botanical specimens. Another early ascent was in 1774 by John Williams, who provided the first account of the mountain's geological structure.[25] John Keats climbed the mountain in 1818, comparing the ascent to "mounting ten St. Pauls without the convenience of a staircase".[26] The following year William MacGillivray, who was later to become a distinguished naturalist, reached the summit only to find "fragments of earthen and glass ware, chicken bones, corks, and bits of paper".[27] It was not until 1847 that Ben Nevis was confirmed by the Ordnance Survey as the highest mountain in Britain and Ireland, ahead of its rival Ben Macdui.

The summit observatory was built in the summer of 1883, and would remain in operation for 21 years. The first path to the summit was built at the same time as the observatory and was designed to allow ponies to carry up supplies, with a maximum gradient of one in five.[19] The opening of the path and the observatory made the ascent of the Ben increasingly popular, all the more so after the arrival of the West Highland Railway in Fort William in 1894.[28] Around this time the first of several proposals was made for a rack railway to the summit, none of which came to fruition.[26]

In 1911, an enterprising Ford dealer named Henry Alexander ascended the mountain in a Model T as a publicity stunt. The ascent was captured on film, and can be seen in the archives of the British Film Institute.[29] A statue of Alexander and the car was unveiled in Fort William in 2018.[30]

In 2000, the Ben Nevis Estate, comprising all of the south side of the mountain including the summit, was bought by the Scottish conservation charity the John Muir Trust.

In 2016, the height of Ben Nevis was officially remeasured to be 1344.527m by Ordnance Survey. The height of Ben Nevis will therefore be shown on new Ordnance Survey maps as 1,345 metres (4,411 ft) instead of the now obsolete value of 1,344 metres (4,409 ft).[1]

Ascent routes

The 1883 Pony Track to the summit (also known as the Ben Path, the Mountain Path or the Tourist Route) remains the simplest and most popular route of ascent. It begins at Achintee on the east side of Glen Nevis about 2 km (1.2 mi) from Fort William town centre, at around 20 metres above sea level. Bridges from the Visitor Centre and the youth hostel now allow access from the west side of Glen Nevis.[12][31] The path climbs steeply to the saddle by Lochan Meall an t-Suidhe (colloquially known as the 'Halfway Lochan') at 570 m, then ascends the remaining 700 metres up the stony west flank of Ben Nevis in a series of zig-zags. The path is regularly maintained but running water, uneven rocks and loose scree make it hazardous and slippery in places. Thanks to the zig-zags, the path is not unusually steep apart from in the initial stages, but inexperienced walkers should be aware that the descent is relatively arduous and wearing on the knees.

A route popular with experienced hillwalkers starts at Torlundy, a few miles north-east of Fort William on the A82 road, and follows the path alongside the Allt a' Mhuilinn. It can also be reached from Glen Nevis by following the Pony Track as far as Lochan Meall an t-Suidhe, then descending slightly to the CIC Hut. The route then ascends Càrn Mòr Dearg and continues along the Càrn Mòr Dearg Arête ("CMD Arête") before climbing steeply to the summit of Ben Nevis. This route involves a total of 1,500 metres of ascent and requires modest scrambling ability and a head for heights.[32] In common with other approaches on this side of the mountain, it has the advantage of giving an extensive view of the cliffs of the north face, which are hidden from the Pony Track.[31]

It is also possible to climb Ben Nevis from the Nevis Gorge car park at Steall at the head of the road up Glen Nevis, either by the south-east ridge or via the summit of Càrn Dearg (south-west). These routes require mild scrambling, are shorter and steeper than the Pony Track, and tend only to be used by experienced hill walkers.

Summit

The summit of Ben Nevis comprises a large stony plateau of about 40 hectares (100 acres).[33] The highest point is marked with a large, solidly built cairn atop which sits an Ordnance Survey trig point. The summit is the highest ground in any direction for 459 miles (739 km) before the Scandinavian Mountains in western Norway are reached.

The ruined walls of the observatory are a prominent feature on the summit. An emergency shelter has been built on top of the observatory tower for the benefit of those caught out by bad weather. Although the base of the tower is slightly lower than the true summit of the mountain, the roof of the shelter overtops the trig point by several feet, making it the highest man-made structure in the UK. A war memorial to the dead of World War II is located next to the observatory.

On 17 May 2006, a piano that had been buried under one of the cairns on the peak was uncovered by the John Muir Trust, which owns much of the mountain.[34][35] The piano is believed to have been carried up for charity by removal men from Dundee over 20 years earlier.[36]

The view from the UK's highest point is extensive. Under ideal conditions, it can extend to over 190 kilometres (120 mi), including such mountains as the Torridon Hills, Morven in Caithness, Lochnagar, Ben Lomond, Barra Head and to Knocklayd in County Antrim, Northern Ireland.[37]

Observatory

A meteorological observatory on the summit was first proposed by the Scottish Meteorological Society (SMS) in the late-1870s, at a time when similar observatories were being built around the world to study the weather at high altitude.[19] In the summer of 1881, Clement Lindley Wragge climbed the mountain daily to make observations (earning him the nickname "Inclement Rag"), leading to the opening on 17 October 1883 of a permanent observatory run by the SMS.[38] The building was staffed full-time until 1904, when it was closed due to inadequate funding. The twenty years worth of readings still provide the most comprehensive set of data on mountain weather in Great Britain.[19]

In September 1894, C. T. R. Wilson was employed at the observatory for a couple of weeks as temporary relief for one of the permanent staff. During this period, he witnessed a Brocken spectre and glory, caused by the sun casting a shadow on a cloud below the observer. He subsequently tried to reproduce these phenomena in the laboratory, resulting in his invention of the cloud chamber, used to detect ionising radiation.[39][40]

Navigation and safety

Ben Nevis's popularity, climate and complex topography contribute to a high number of mountain rescue incidents. In 1999 there were 41 rescues and four fatalities on the mountain.[5] It has also been estimated that there are several deaths annually on Ben Nevis.[41]

Avalanches

In two avalanches that occurred on Ben Nevis in 2009[42] and 2016[43] two people died on both occasions. In two avalanches that occurred in 1970[44] and 2019[45] three people died on both occasions. A climber died in an avalanche on the north face in 2022.[46]

Navigation

Some accidents arise over difficulties in navigating to or from the summit,[47] especially in poor visibility. The problem stems from the fact that the summit plateau is roughly kidney-shaped and surrounded by cliffs on three sides; the danger is particularly accentuated when the main path is obscured by snow. Two precise compass bearings taken in succession are necessary to navigate from the summit cairn to the west flank, from where a descent can be made on the Pony Track in relative safety.[48]

In the late 1990s, Lochaber Mountain Rescue Team erected two posts on the summit plateau to assist walkers attempting the descent in foggy conditions. These posts were subsequently cut down by climbers, sparking controversy in mountaineering circles on the ethics of such additions.[47][49] Critics argued that cairns and posts are an unnecessary man-made intrusion into the natural landscape, which create a false sense of security and could lessen mountaineers' sense of responsibility for their own safety.[49]

Supporters of navigational aids pointed to the high number of accidents that occurred on the mountain. Between 1990 and 1995 alone there were 13 fatalities, although eight of these were due to falls while rock climbing rather than navigational error.[47] Also there is a long tradition of placing such aids on the summit, and the potentially life-saving role they could play.

In 2016, the John Muir Trust cleared a number of smaller informal cairns which had recently been erected by visitors, many near the top of gullies, which were seen as dangerous as they could confuse walkers using them for navigation.[50] As of 2019, a series of solidly-constructed cairns, each several feet high, marks the upper reaches of the Pony Track and the path across the summit plateau.

Climbing on Ben Nevis

The north face of Ben Nevis is riven with buttresses, ridges, towers and pinnacles, and contains many classic scrambles and rock climbs. It is of major importance for British winter climbing, with many of its routes holding snow often until late April. It was one of the first places in Scotland to receive the attention of serious mountaineers; a partial ascent and, the following day, a complete descent of Tower Ridge in early September 1892 is the earliest documented climbing expedition on the Ben.[51][52] (It was not climbed from bottom to top in entirety for another two years). The Scottish Mountaineering Club's Charles Inglis Clark hut was built below the north face in Coire Leis in 1929. Because of its remote location, it is said to be the only genuine alpine hut in Britain.[13] It remains popular with climbers, especially in winter.

Tower Ridge is the longest of the north face's four main ridges, with around 600 metres of ascent. It is not technically demanding (its grade is Difficult), and most pitches can be tackled unroped by competent climbers, but it is committing and very exposed.[51] Castle Ridge (Moderate), the northernmost of the main ridges, is an easier scramble, while Observatory Ridge (Very Difficult),[53] the closest ridge to the summit, is "technically the hardest of the Nevis ridges in summer and winter".[54] Between the Tower and Observatory Ridges are the Tower and Gardyloo Gullies; the latter takes its name from the cry of "garde à l'eau" (French for "watch out for the water") formerly used in Scottish cities as a warning when householders threw their waste out of a tenement window into the street. The gully's top wall was the refuse pit for the now-disused summit observatory.[8] The North-east Buttress (Very Difficult) is the southernmost and bulkiest of the four ridges; it is as serious as Observatory Ridge but not as technically demanding, mainly because an "infamous"[55] rock problem, the 'Man-trap', can be avoided on either side.

The north face contains dozens of graded rock climbs along its entire length, with particular concentrations on the Càrn Dearg Buttress (below the Munro top of Càrn Dearg NW) and around the North-east Buttress and Observatory Ridge. Classic rock routes include Rubicon Wall on Observatory Buttress (Severe) – whose second ascent in 1937, when it was considered the hardest route on the mountain, is described by W. H. Murray in Mountaineering in Scotland[56] – and, on Càrn Dearg, Centurion and The Bullroar (both HVS), Torro (E2), and Titan's Wall (E3), these four described in the SMC's guide as among "the best climbs of their class in Scotland".[55]

Many seminal lines were recorded before the First World War by pioneering Scottish climbers like J. N. Collie, Willie Naismith, Harold Raeburn, and William and Jane Inglis Clark. Other classic routes were put up by G. Graham Macphee, Dr James H. B. Bell and others between the Wars; these include Bell's 'Long Climb', at 1,400 ft (430 m) reputedly the longest sustained climb on the British mainland. In summer 1943 conscientious objector Brian Kellett made a phenomenal seventy-four repeat climbs and seventeen first ascents including fourteen solos,[54] returning in 1944 to add fifteen more new lines, eleven solo, including his eponymous HVS on Gardyloo buttress. Much more recently, an extreme and as yet ungraded climb on Echo Wall was completed by Dave MacLeod in 2008 after two years of preparation.[57]

The north face is also one of Scotland's foremost venues for winter mountaineering and ice climbing, and holds snow until quite late in the year; in a good year, routes may remain in winter condition until mid-spring. Most of the possible rock routes are also suitable as winter climbs, including the four main ridges; Tower Ridge, for example, is grade IV on the Scottish winter grade, having been upgraded in 2009 by the Scottish Mountaineering Club after requests by the local Mountain Rescue Team, there being numerous benightments and incidents every winter season.[58] Probably the most popular ice climb on Ben Nevis[59] is The Curtain (IV,5) on the left side of the Càrn Dearg Buttress. At the top end of the scale, Centurion in winter is a grade VIII,8 face climb.

In February 1960 James R. Marshall and Robin Clark Smith recorded six major new ice routes in only eight days including Orion Direct (V,5 400m); this winter version of Bell's Long Climb was "the climax of a magnificent week's climbing by Smith and Marshall, and the highpoint of the step-cutting era".[55]

Ben Nevis Race

The history of hill running on Ben Nevis dates back to 1895. William Swan, a barber from Fort William, made the first recorded timed ascent up the mountain on or around 27 September of that year, when he ran from the old post office in Fort William to the summit and back in 2 hours 41 minutes.[28] The following years saw several improvements on Swan's record, but the first competitive race was held on 3 June 1898 under Scottish Amateur Athletic Association rules. Ten competitors ran the course, which started at the Lochiel Arms Hotel in Banavie and was thus longer than the route from Fort William; the winner was 21-year-old Hugh Kennedy, a gamekeeper at Tor Castle, who finished (coincidentally with Swan's original run) in 2 hours 41 minutes.[28]

Regular races were organised until 1903, when two events were held; these were the last for 24 years, perhaps due to the closure of the summit observatory the following year.[28] The first was from Achintee, at the foot of the Pony Track, and finished at the summit; It was won in just over an hour by Ewen MacKenzie, the observatory roadman.[28] The second race ran from new Fort William post office, and MacKenzie lowered the record to 2 hours 10 minutes, a record he held for 34 years.[28]

The Ben Nevis Race has been run in its current form since 1937. It now takes place on the first Saturday in September every year, with a maximum of 500 competitors taking part.[60] It starts and finishes at the Claggan Park football ground on the outskirts of Fort William, and is 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) long with 1,340 metres (4,400 ft) of ascent.[61] Due to the seriousness of the mountain environment, entry is restricted to those who have completed three hill races, and runners must carry waterproofs, a hat, gloves and a whistle; anyone who has not reached the summit after two hours is turned back.[62] As of 2018, the record for the men's race has stood unbroken since 1984, when Kenny Stuart of Keswick Athletic Club won with a time of 1:25:34. The record for the women's race of 1:43:01 was set in 2018 by Victoria Wilkinson.[61]

Extreme sports on The Ben

Ben Nevis is becoming popular with ski mountaineers and boarders. The Red Burn (Allt Coire na h-Urcaire) just to the North of the tourist path gives the easiest descent, but most if not all of the easier gullies on the North Face have been skied, as has the slope once adorned by the abseil poles into Coire Leis. No 4 gully is probably the most skied. Although Tower scoop makes it a no-fall zone, Tower Gully is becoming popular, especially in May and June when there is spring snow.[63]

In 2018 Jöttnar pro team member Tim Howell BASE jumped off Ben Nevis which was covered by BBC Scotland.[64]

On 6 May 2019, a team of highliners completed a crossing above the Gardyloo Gully, a new altitude record for the UK.[65]

Also in May 2019, a team of 12, led by Dundee artist Douglas Roulston carried a 5-foot (1.5-metre) tall statue of the DC Thomson character Oor Wullie to the top of the mountain. The statue, which had been painted by Roulston with a 360 degree scene of the view from the summit was later sold at the Oor Wullie Big Bucket Trail charity auction to raise money for a number of Scottish children's charities.

Environmental issues and Nevis Landscape Partnership

Ben Nevis's popularity and high-profile have led to concerns in recent decades over the impact of humans on the fragile mountain environment within the Ben Nevis and Glen Coe National Scenic Area. These concerns contributed to the creation of The Nevis Landscape Partnership,[66] a five-year programme which aimed to protect, enhance and future-proof Ben Nevis by delivering nineteen ambitious environmental projects between 2014 and 2019. The Nevis Landscape Partnership is supported by five partner organisations (John Muir Trust, Forestry Commission Scotland, The Highland Council, Scottish Natural Heritage and The Nevis Partnership) and was made possible by Heritage Lottery Funding.

With the 5-year programme now finished, there have been significant positive changes implemented by Nevis Landscape Partnership and their projects, most significantly the upgrades to the Ben Nevis Mountain Track. Work to upgrade the mountain track started in November 2015 after two contracts were awarded to McGowan Ltd. and Cairngorm Wilderness Contracts. Between 2015 and 2019, 3.5 km of path has been repaired through eight separate contracts and 3,323 hours of volunteer time.

Volunteers help to maintain the mountain track. Nevis Landscape Partnership and National Trust for Scotland have run Thistle Camp Working Holidays[67] which have focused on maintenance on the first section of the Ben Nevis footpath.

Ben Nevis Distillery

The Ben Nevis Distillery is a single malt whisky distillery at the foot of the mountain, near Victoria Bridge to the north of Fort William. Founded in 1825 by John McDonald (known as "Long John"), it is one of the oldest licensed distilleries in Scotland,[68][69] and is a popular visitor attraction in Fort William. The water used to make the whisky comes from the Allt a' Mhuilinn, the stream that flows from Ben Nevis's northern corrie.[70] "Ben Nevis" 80/‒ organic ale is, by contrast, brewed in Bridge of Allan near Stirling.[71]

Other uses

Ben Nevis was the name of a White Star Line packet ship which in 1854 carried the group of immigrants who were to become the Wends of Texas.[72] At least another eight vessels have carried the name since then.[73]

A mountain in Svalbard is also named Ben Nevis, after the Scottish peak. It is 922 metres high, and is south of the head of Raudfjorden, Albert I Land, in the northwestern part of the island of Spitsbergen.[74]

A comic strip character, Wee Ben Nevis, about a Scottish Highlands boarding school student with superhuman strength and his antics were featured in the British comic The Beano from 1974 to 1977, named after the mountain.

Hung Fa Chai, a 489-metre hill in Northeast New Territories of Hong Kong was marked as Ben Nevis on historical colonial maps.

See also

- Mountains and hills of Scotland

- National Three Peaks Challenge

- Northwest Spitsbergen National Park Norway - includes a mountain called Ben Nevis. Its height is 918 metres and it is located at Northwest Spitsbergen National Park

- The Remarkables, New Zealand – mountain range containing a peak also called Ben Nevis

- Scottish Highlands

- Scafell Pike

- Snowdon

Footnotes

- ^ This is the distance to the mountain Melderskin in Norway.

References

- Notes

- ^ a b c "Great Britain's tallest mountain is taller". Ordnance Survey. 18 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ Mitchell, Ian R. (2004). Scotland's Mountains Before the Mountaineers. Luath Press Limited. p. 33.

- ^ "Isolation for Ben Nevis - Peakbagger.com". www.peakbagger.com.

- ^ "Ben Nevis". John Muir Trust. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ a b The Nevis Working Party (2001). "Nevis Strategy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 5 November 2006.

- ^ a b "How volcanoes shaped Britain's landscape". BBC News. 5 July 2012.

- ^ MacBain, Alexander (1922). Place names Highlands & Islands of Scotland. p. 156. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ a b c W. H. Murray, The Companion Guide to the West Highlands of Scotland

- ^ a b Butterfield, The High Mountains, p. 96

- ^ "Ben Nevis, or the 'Ben' as it is fondly known locally". Visit Fort William Ltd. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ^ "Ben Nevis is almost always referred to by climbers as simply The Ben (Ben meaning Mountain)". The Ben Nevis Challenge. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ^ a b Ordnance Survey Landranger 41.

- ^ a b Scottish Mountaineering Club website. "Charles Inglis Clark Memorial Hut (C.I.C.)". Archived from the original on 15 September 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ Derek A. Bearhop (1997). Munro's Tables. Scottish Mountaineering Club & Trust. ISBN 978-0-907521-53-2.

- ^ "Geology of Ben Nevis". ben-nevis.com. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- ^ Averis, A. B. G.; Averis, A. M. (2005). "A survey of the vegetation of Ben Nevis Site of Special Scientific Interest and Special Area of Conservation, 2003–2004" (PDF). Scottish National Heritage Commissioned Report. 090. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2006.

- ^ McKirdy, Alan; Gordon, John & Crofts, Roger (2007). Land of Mountain and Flood: The Geology and Landforms of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. Pages 114–116.

- ^ Gillen, Con (2003) Geology and landscapes of Scotland. Harpenden. Terra. Page 80.

- ^ a b c d e Marjorie Roy (2004). "The Ben Nevis Meteorological Observatory 1883–1904" (PDF). International Commission on History of Meteorology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 27 November 2006.

- ^ a b Murray, Companion Guide, p. 221

- ^ Eric Langmuir (1995). Mountaincraft and Leadership (Third ed.). Edinburgh: SportScotland. ISBN 978-1-85060-295-8.

- ^ "Meteorological Observations taken from Ben Nevis and Fort William (1883 -1904)". Centre for Environmental Data Analysis. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: The Meteorology of the Ben Nevis Observations". Royal Society of Edinburgh. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ Henderson, D.M.; Dickson, J.H. (1994). A Naturalist in the Highlands: James Robertson, His Life and Travels in Scotland 1767-1771. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-7073-0734-3.

- ^ Suzanne Miller (2004). "Ben Nevis Geology". The Edinburgh Geologist. 43: 3–9.

- ^ a b Hodgkiss, The Central Highlands, p. 117

- ^ Hunter, Andrew (September 2014). "Bones on Ben Nevis – a walk back into history". Leopard Magazine: 30–34. ISSN 2053-9851.

- ^ a b c d e f Hugh Dan MacLennan (November 1998). "The Ben Race: The supreme test of athletic fitness" (PDF). The Sports Historian. 18 (2): 131–147. doi:10.1080/17460269809445800. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ^ "Motoring over Ben Nevis". The British Film Institute. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ MacLennan, Chris (21 May 2018). "Bronze Ford Model T unveiled in Fort William". The Press and Journal. Aberdeen. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ a b Butterfield, The High Mountains, p. 97

- ^ Butterfield, The High Mountains, p. 98

- ^ "Ben Nevis". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 November 2006. (Subscription required for full access.)

- ^ "Piano found on Britain's highest mountain". The Guardian. London. 17 May 2006. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ "New twist in Nevis music mystery". BBC News. 18 May 2006. Retrieved 22 June 2006.

- ^ "Trust names Ben Nevis 'piano men'". BBC News. 19 May 2006. Retrieved 15 August 2006.

- ^ Viewfinder Panoramas: North, South. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- ^ Crocket, Ken (1986). Ben Nevis : Britain's highest mountain. Glasgow: Scottish Mountaineering Trust. pp. 41–44. ISBN 978-0907521167.

- ^ Nobel Foundation (1965). "C. T. R. Wilson Biography from Nobel Lectures, Physics 1922–1941, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam". Retrieved 27 November 2006.

- ^ YouTube. Archived from the original on 7 April 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ Arnette, Alan. "About Ben Nevis". Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Carrell, Severin (30 December 2009). "Ben Nevis avalanche kills two climbers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Missing Ben Nevis couple were hit by 'massive avalanche'". The Herald (Glasgow). 24 March 2016. Archived from the original on 4 July 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ "Rescuer tells of horror as Glencoe avalanche kills three climbers: "There were hundreds of tons of snow"". The Scotsman. 25 January 2009. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ Carrell, Severin (12 March 2019). "Ben Nevis avalanche kills three people". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ "Bristol teacher killed in Ben Nevis avalanche". BBC News. 5 January 2023. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ a b c The Mountaineering Council of Scotland (1997). "Ben Nevis—The Future". Newsletter. 33.

- ^ "Navigation on Ben Nevis". www.mcofs.org.uk. Mountaineering Scotland. Retrieved 30 October 2016.

- ^ a b The Mountaineering Council of Scotland. "Summit Safety and Ben Nevis Cairns: The MCofS seeks a resolution" (also see sub-pages). Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- ^ Shute, Joe (6 March 2016). "The deadly secret of Ben Nevis's man-made cairns". Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ a b Terry Adby & Stuart Johnston (2003). The Hillwalker's Guide to Mountaineering. Milnthorpe: Cicerone. pp. 240–247. ISBN 978-1-85284-393-9.

- ^ Hodgkiss, The Central Highlands, p. 119

- ^ Hodgkiss, The Central Highlands, p. 126

- ^ a b Crocket, Ken; Richardson, Simon (2009). Ben Nevis: Britain's Highest Mountain (second ed.). Glasgow: Scottish Mountaineering Trust. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-907233-10-4.

- ^ a b c Richardson, Simon (2002). Ben Nevis: Rock and Ice Climbs. Glasgow: Scottish Mountaineering Trust. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-907521-73-0.

- ^ W. H. Murray [1947] (1962). Mountaineering in Scotland. London: J. M. Dent.

- ^ "MacLeod's Boldest: Echo Wall". Alpinist.com. Retrieved 22 February 2006.

- ^ "Climbing on Ben Nevis". Scottish Climbing Archive. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006. Retrieved 26 October 2006.

- ^ Hodgkiss, The Central Highlands, p. 130

- ^ "Ben Nevis Race – a brief history". Fort William Online. Archived from the original on 2 January 2007. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- ^ a b "Ben Nevis Race". www.scottishhillracing.co.uk. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ Bob Kopac. "For Sport Alone: The Ben Nevis Race". MHRRC Online. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- ^ Kenny Biggin, Scottish Offpiste Skiing and Snowboarding: Nevis Range and Ben Nevis (Spean Bridge: Skimountain, 2013), pp. 64–84

- ^ "Base jumper Tim Howell leaps from Ben Nevis". BBC Scotland, 12 February 2019

- ^ "In pictures: UK's highest altitude highline completed on Ben Nevis". BBC News. BBC. 5 July 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ "Nevis Landscape Partnership". www.nevislandscape.co.uk.

- ^ "Thistle Camps - Home : Welcome". 25 January 2020. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020.

- ^ "Ben Nevis Distillery". Archived from the original on 25 November 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- ^ "Ben Nevis". Edinburgh Malt Whisky Tour. Archived from the original on 10 October 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- ^ "Ben Nevis Distillery". Scotchwhisky.net. Archived from the original on 29 December 2006. Retrieved 25 November 2006.

- ^ "Ben Nevis ale". Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2006.

- ^ Lammert, Ron (January 2010). "Texas Wendish Heritage Society: Brief History". Texas Wendish Heritage Society.

- ^ "Miramar Ship Index". Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ "Place names in Norwegian polar areas". Norwegian Polar Institute. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- Bibliography

- Butterfield, Irvine (1986). The High Mountains of Britain and Ireland. London: Diadem Books. pp. 96–99. ISBN 978-0-906371-71-8.

- Crocket, Ken; Richardson, Simon (2009). Ben Nevis: Britain's Highest Mountain: 2nd Edition. The Scottish Mountaineering Trust. ISBN 978-1-907233-10-4.

- Hodgkiss, Peter (1994). The Central Highlands (5th ed.). Scottish Mountaineering Trust. pp. 116–134. ISBN 978-0-907521-44-0.

- Irving, R. L. G. (1940). Ten Great Mountains. London: J. M. Dent & Sons.

- Ordnance Survey. (2002). Landranger 41: Ben Nevis (Map). Ordnance Survey. ISBN 0-319-22641-7.

- Murray, W. H. (1977). The Companion Guide to the West Highlands of Scotland. London: Collins. pp. 218–221. ISBN 978-0-00-216813-7.

- Richardson, Simon (2002). Ben Nevis: Rock and Ice Climbs. The Scottish Mountaineering Trust. ISBN 978-0-907521-73-0.

External links

- Ben Nevis Photo Tour – 57 images from the Car Park to the Summit and Back via the Tourist Trail

- Nevis Partnership – Environmental and visitor management in the Nevis area

- Computer generated digital panoramas from Ben Nevis: North South index

- Ben Nevis Webcam

- 360munros.co.uk - Ben Nevis 360° Virtual Tours

- Ben Nevis. Munros Table. Scottish Mountaineering Club.