Colony of New Jersey

New Jersey | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1664–1673 1702–1776 | |||||||||||||||||

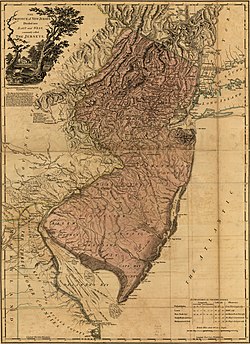

The Province of New Jersey, Divided into East and West, commonly called The Jerseys, 1777 map by William Faden | |||||||||||||||||

| Status | Proprietary Colony of England (1664–1673) Royal Colony of England (1702–1707) Royal Colony of Great Britain (1707–1776) | ||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Elizabethtown (1664–1673) Perth Amboy and Burlington (1702–1776) | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | English, Dutch | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Church of England (Official) | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Proprietary colony (1664-1673) Royal colony (1702-1776) | ||||||||||||||||

| Lords Proprieter | |||||||||||||||||

• 1664-1673 | Lord Berkeley of Stratton Sir George Carteret | ||||||||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||||||||

• 1664-1665 | Richard Nicolls (first) | ||||||||||||||||

• 1672-1673 | John Berry (last) | ||||||||||||||||

| Royal Governor | |||||||||||||||||

• 1702-1708 | Lord Cornbury (first) | ||||||||||||||||

• 1763-1776 | William Franklin (last) | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Council General Assembly Provincial Congress (1775-1776) | ||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• 1609 | 1664 | ||||||||||||||||

• 1666 | 1776 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | New Jersey pound | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | United States | ||||||||||||||||

| History of New Jersey |

|---|

|

| Colonial period |

| American Revolution |

| Nineteenth century |

| Twentieth century |

| Twenty-first century |

The Province of New Jersey was one of the Middle Colonies of Colonial America and became the U.S. state of New Jersey in 1776. The province had originally been settled by Europeans as part of New Netherland but came under English rule after the surrender of Fort Amsterdam in 1664, becoming a proprietary colony. The English renamed the province after the island of Jersey in the English Channel. The Dutch Republic reasserted control for a brief period in 1673–1674. After that it consisted of two political divisions, East Jersey and West Jersey, until they were united as a royal colony in 1702. The original boundaries of the province were slightly larger than the current state, extending into a part of the present state of New York, until the border was finalized in 1773.[1]

Background

The Province of New Jersey was originally settled in the 1610s as part of the colony of New Netherland. The surrender of Fort Amsterdam in September 1664 gave control over the entire Mid-Atlantic region to the English as part of the Second Anglo-Dutch War. The English justified the seizure by claiming that John Cabot, an Italian under the sponsorship of the English King Henry VII, had been the first to discover the place, but it was probably to assert control over the profitable North Atlantic trade. Director-General of New Netherland Peter Stuyvesant, unable to rouse a military defense, relinquished control of the colony and was able in the articles of transfer to secure guarantees for property rights, laws of inheritance, and freedom of religion. After the surrender, Richard Nicolls took the position as deputy-governor of New Amsterdam and the rest of New Netherland, including those settlements on the west side of the North River (Hudson River) known as Bergen and those along the Delaware River that had been New Sweden.

Proprietary government

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1670 | 1,000 | — |

| 1680 | 3,400 | +240.0% |

| 1690 | 8,000 | +135.3% |

| 1700 | 14,010 | +75.1% |

| 1710 | 19,872 | +41.8% |

| 1720 | 29,818 | +50.1% |

| 1730 | 37,510 | +25.8% |

| 1740 | 51,373 | +37.0% |

| 1750 | 71,393 | +39.0% |

| 1760 | 93,813 | +31.4% |

| 1770 | 117,431 | +25.2% |

| 1780 | 139,627 | +18.9% |

| 1784 | 149,435 | +7.0% |

| Source: 1670–1760;[2] 1784[3] 1770–1780[4] | ||

In March 1664, King Charles II granted his brother, James, the Duke of York, a Royal colony that covered New Netherlands and present-day Maine.[5] This charter also included parts of present-day Massachusetts, which conflicted with that colony's charter. The charter allowed James traditional propriety rights and imposed few restrictions upon his powers. In general terms, the charter was equivalent to a conveyance of land conferring on him the right of possession, control, and government, subject only to the limitation that the government must be consistent with the laws of England. The Duke of York never visited his colony and exercised little direct control of it. He elected to administer his government through governors, councils, and other officers appointed by himself. No provision was made for an elected assembly.

Later in 1664, the Duke of York gave the part of his new possessions between the Hudson River and the Delaware River to Sir George Carteret in exchange for settlement of a debt.[7] The territory was named after the island of Jersey, Carteret's ancestral home.[8] The other section of New Jersey was sold to Lord Berkeley of Stratton, who was a close friend of the Duke. As a result, Carteret and Berkeley became the two English lords proprietors of New Jersey.[9][10] The two proprietors of New Jersey attempted to attract more settlers to move to the province by granting sections of lands to settlers and by passing the Concession and Agreement, a 1665 document that granted religious freedom to all inhabitants of New Jersey;[11] under the British government, there was no such religious freedom as the Church of England was the state church. In return for the land, the settlers were supposed to pay annual fees known as quit-rents.

In 1665, Philip Carteret became the first governor of New Jersey, appointed by the two proprietors. He selected Elizabeth as the capital of New Jersey. Immediately, Carteret issued several additional grants of land to landowners. Towns were started and charters granted to Newark (1666), Piscataway (1666), Bergen (1668), Middletown (1693), Woodbridge (1669), and Shrewsbury.

The idea of quit-rents became increasingly difficult because many of the settlers refused to pay them. Most of them claimed that they owed nothing to the proprietors because they received land from Richard Nicolls, governor of New York. This forced Berkeley to sell West Jersey to John Fenwick and Edward Byllynge, two English Quakers. Many more Quakers made their homes in New Jersey, seeking religious freedom from English (Church of England) rule.

Meanwhile, conflicts began rising in New Jersey. Edmund Andros, governor of New York, attempted to gain authority over East Jersey after the death of Sir George Carteret in 1680. However, he was unable to remove the position of governorship from Governor Phillip Carteret and subsequently moved to attack him and brought him to trial in New York. Carteret was later acquitted. In addition, quarrels occurred between Eastern and Western New Jerseyans, between Native Americans and New Jerseyans, and between different religious groups.

East and West Jerseys

by John Thorton, surveyed by John Worlidge

From 1674 to 1702, the Province of New Jersey was divided into East Jersey and West Jersey, each with its own governor. Each had its own constitution: the West Jersey Constitution (1681) and the East Jersey Constitution (1683).[12][13]

The exact border between West and East Jersey was often disputed. The border between the two sides reached the Atlantic Ocean to the north of present-day Atlantic City. The border line was created by George Keith and can still be seen in the county boundaries between Burlington and Ocean counties, and between Hunterdon and Somerset counties. The Keith line runs north-northwest from the southern part of Little Egg Harbor Township, passing just north of Tuckerton, and reaching upward to a point on the Delaware River which is just north of the Delaware Water Gap. Later, the 1676 Quintipartite Deed helped to lessen the disputes. More accurate surveys and maps were made to resolve property disputes. This resulted in the Thornton Line, drawn around 1696, and the Lawrence Line, drawn around 1743, which was adopted as the final line for legal purposes.[14]

Dominion of New England

The Dominion of New England was a short-lived administrative union. On May 7, 1688, the Province of New York, the Province of East Jersey, and the Province of West Jersey were added to the Dominion. The capital was located in Boston, but because of its size, New York, East Jersey, and West Jersey were run by the lieutenant governor from New York City. After news of the overthrow of James II by William of Orange in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 reached Boston, the colonists rose up in rebellion, and the Dominion was dissolved in 1689.

Royal colony

On April 17, 1702, under the rule of Queen Anne, the two sections of the proprietary colony were united, and New Jersey became a royal colony. Edward Hyde, Lord Cornbury, became the first governor of the colony as a royal colony. However, he was an ineffective and corrupt ruler, taking bribes and speculating on land. In 1708, Lord Cornbury was recalled to England. New Jersey was then again ruled by the governors of New York, but this infuriated the settlers of New Jersey, accusing those governors of favoritism to New York. Judge Lewis Morris led the case for a separate governor and was appointed governor by King George II in 1738.[15]

New York–New Jersey Line War

The New York – New Jersey Line War was a series of skirmishes and raids that took place for over half a century between 1701 and 1765 at the disputed border between the two American colonies the Province of New York and the Province of New Jersey. Border wars were not unusual in the early days of settlements of the colonies and originated in conflicting land claims. Because of ignorance, willful disregard, and legal ambiguities, such conflicts arose involving local settlers until a final settlement was reached. In the largest of these squabbles some 210,000 acres (850 km2) of land were at stake between New York and New Jersey. The conflict was eventually settled by royal commission in 1769.

Provincial Congress

1777 map by William Faden

The Provincial Congress of New Jersey was a transitional governing body of the Province of New Jersey in the early part of the American Revolution. It first met in 1775 with representatives from all New Jersey's thirteen counties, to supersede the royal governor.

First state constitution

New Jersey's first state constitution was adopted on July 2, 1776.[16] The American Revolutionary War was underway, and General George Washington recently had been defeated in New York, putting the state in danger of invasion.[16] The 1776, the New Jersey State Constitution was drafted in five days and ratified within the next two days to establish a temporary government, thereby preventing New Jersey from collapsing and descending into anarchy.[17] Among other provisions, it granted unmarried women and blacks who met property requirements the right to vote.[16]

Judiciary

The Supreme Court was established in 1704, to sit alternately at Perth Amboy and Burlington, consisting of a chief justice, a second judge and several associate judges.

- Chief justices [18]

| Incumbent | Tenure | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Took office | Left office | ||

| Roger Mompesson | Oct 1704 | 1709 | |

| Thomas Gordon | April 28, 1709 | 1709 | |

| Roger Mompesson | 1709 | February 14, 1710 | |

| David Jamison (politician) | 1710 | 1723 | |

| William Trent | November 23, 1723 | December 25, 1724 | |

| Robert Lettis Hooper | January 2, 1725 | 1728 | |

| Thomas Farmar | 1728 | 1728 | |

| Robert Lettis Hooper | 1729 | 1738 | |

| Robert Hunter Morris | March 17, 1739 | January 27, 1757 | disputed resignation in 1754, left for England 1757 |

| William Aynsley | February 16, 1757 | May 1758 | |

| Robert Hunter Morris | 1761 | January 27, 1764 | restored to office |

| Charles Reade | February 20, 1764 | 1764 | |

| Frederick Smyth | October 17, 1764 | 1766 | |

See also

- Elizabethtown Tract

- Horseneck Tract

- English Neighborhood

- Colonial government in the Thirteen Colonies (Council and Assembly)

- Robert Treat

- List of the oldest buildings in New Jersey

References

- ^ The New York – New Jersey Line War (also known as the "N.J. Line War") refers to a series of skirmishes and raids that took place between 1701 and 1765 at the disputed border between two American colonies — the Province of New Jersey and the Province of New York.

- ^ Purvis, Thomas L. (1999). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Colonial America to 1763. New York: Facts on File. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-0816025275.

- ^ Purvis, Thomas L. (1995). Balkin, Richard (ed.). Revolutionary America 1763 to 1800. New York: Facts on File. p. 153. ISBN 978-0816025282.

- ^ "Colonial and Pre-Federal Statistics" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. p. 1168.

- ^ "Timeline". New York State Senate. February 13, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ Jan Mertens (October 13, 2008). "New Jersey: Tricentennial flag". Flags of the World. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ Turner, Jean-Rae and Richard T. Koles (August 27, 2003). Elizabeth: First Capital of New Jersey. Arcadia Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 0738523933.

- ^ The province was also called "the Province of New Caesaria or New Jersey". See: Philip Carteret.

- ^ Rieff, Henry, "Interpretations of New York-New Jersey Agreements 1834 and 1921" (PDF), Newark Law Review, 1 (2), archived from the original (PDF) on May 6, 2006

- ^ "Land Speculation and Proprietary Beginnings of New Jersey" (PDF). The Advocate. New Jersey Land Title Association. XVI (4): 3, 20, 14. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- ^ The Concession and Agreement was the first of three fundamental documents that governed the Province of New Jersey. See: New Jersey State Constitution#Previous versions. See also: History of the New Jersey State Constitution. For the other two fundamental documents, see #East and West Jerseys.

- ^ Avalon Project. "Province of West New-Jersey, in America, The 25th of the Ninth Month Called November". Yale Law School. Archived from the original on January 2, 2007. Retrieved December 17, 2006. Avalon Project. "The Fundamental Constitutions for the Province of East New Jersey in America, Anno Domini 1683". Yale Law School. Archived from the original on December 5, 2006. Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- ^ See: New Jersey State Constitution#Previous versions. See also: History of the New Jersey State Constitution. In addition to these two fundamental documents, a third such document was the Concession and Agreement. See: #Settlement and early history.

- ^ Aun, Fred (January 1995). "A Fine Old Line Across New Jersey". Coordinate. 15 (1). Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ Streissguth pg 30–36

- ^ a b c See: New Jersey State Constitution#Previous versions.

- ^ "The New Jersey Constitution of 1776". Retrieved December 17, 2006.

- ^ Tanner, Edwin. The province of New Jersey, 1664-1738 (Volume 1).

Further reading

- Cunningham, John T. Colonial New Jersey (1971) 160pp

- Doyle, John Andrew. English Colonies in America: Volume IV The Middle Colonies (1907) online ch 7–8

- McCormick, Richard P. New Jersey from Colony to State, 1609–1789 (1964) 191pp

- Pomfret, John Edwin. Colonial New Jersey: a history (1973), the standard modern history

External links

- Colonial Charters, Grants and Related Documents (at "New Jersey").