Digital warfare

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

Cyberwarfare is the use of cyber attacks against an enemy state, causing comparable harm to actual warfare and/or disrupting vital computer systems.[1] Some intended outcomes could be espionage, sabotage, propaganda, manipulation or economic warfare.

There is significant debate among experts regarding the definition of cyberwarfare, and even if such a thing exists.[2] One view is that the term is a misnomer since no cyber attacks to date could be described as a war.[3] An alternative view is that it is a suitable label for cyber attacks which cause physical damage to people and objects in the real world.[4]

Many countries, including the United States, United Kingdom, Russia, China, Israel, Iran, and North Korea,[5][6][7][8] have active cyber capabilities for offensive and defensive operations. As states explore the use of cyber operations and combine capabilities, the likelihood of physical confrontation and violence playing out as a result of, or part of, a cyber operation is increased. However, meeting the scale and protracted nature of war is unlikely, thus ambiguity remains.[9]

The first instance of kinetic military action used in response to a cyber-attack resulting in the loss of human life was observed on 5 May 2019, when the Israel Defense Forces targeted and destroyed a building associated with an ongoing cyber-attack.[10][11]

Definition

There is ongoing debate over how cyberwarfare should be defined and no absolute definition is widely agreed upon.[9][12] While the majority of scholars, militaries, and governments use definitions that refer to state and state-sponsored actors,[9][13][14] other definitions may include non-state actors, such as terrorist groups, companies, political or ideological extremist groups, hacktivists, and transnational criminal organizations depending on the context of the work.[15][16]

Examples of definitions proposed by experts in the field are as follows.

'Cyberwarfare' is used in a broad context to denote interstate use of technological force within computer networks in which information is stored, shared, or communicated online.[9]

Raymond Charles Parks and David P. Duggan focused on analyzing cyberwarfare in terms of computer networks and pointed out that "Cyberwarfare is a combination of computer network attack and defense and special technical operations."[17] According to this perspective, the notion of cyber warfare brings a new paradigm into military doctrine. Paulo Shakarian and colleagues put forward the following definition of "cyber war" in 2013, drawing on Clausewitz's definition of war: "War is the continuation of politics by other means":[13]

Cyber war is an extension of policy by actions taken in cyber space by state or nonstate actors that constitute a serious threat to a nation's security or are conducted in response to a perceived threat against a nation's security.

Taddeo offered the following definition in 2012:

The warfare grounded on certain uses of ICTs within an offensive or defensive military strategy endorsed by a state and aiming at the immediate disruption or control of the enemy's resources, and which is waged within the informational environment, with agents and targets ranging both on the physical and non-physical domains and whose level of violence may vary upon circumstances.[18]

Robinson et al. proposed in 2015 that the intent of the attacker dictates whether an attack is warfare or not, defining cyber warfare as "the use of cyber attacks with a warfare-like intent."[12]

In 2010, the former US National Coordinator for Security, Infrastructure Protection and Counter-terrorism, Richard A. Clarke, defined cyberwarfare as "actions by a nation-state to penetrate another nation's computers or networks for the purposes of causing damage or disruption".[14] The target's own cyber-physical infrastructure may be used by the adversary in case of a cyber conflict, thus weaponizing it.[19]

Controversy of term

There is debate on whether the term "cyber warfare" is accurate. In 2012, Eugene Kaspersky, founder of Kaspersky Lab, concluded that "cyberterrorism" is a more accurate term than "cyberwar." He states that "with today's attacks, you are clueless about who did it or when they will strike again. It's not cyber-war, but cyberterrorism."[20] Howard Schmidt, former Cyber Security Coordinator in the Obama administration, said that "there is no cyberwar... I think that is a terrible metaphor and I think that is a terrible concept. There are no winners in that environment."[21]

Some experts take issue with the possible consequences linked to the warfare goal. In 2011, Ron Deibert, of Canada's Citizen Lab, warned of a "militarization of cyberspace", as militaristic responses may not be appropriate.[22] However, to date, even serious cyber-attacks that have disrupted large parts of a nation's electrical grid (230,000 customers, Ukraine, 2015) or affected access to medical care, thus endangering life (UK National Health Service, WannaCry, 2017) have not led to military action.[23]

In 2017, Oxford academic Lucas Kello proposed a new term, "Unpeace", to denote highly damaging cyber actions whose non-violent effects do not rise to the level of traditional war. Such actions are neither warlike nor peace-like. Although they are non-violent, and thus not acts of war, their damaging effects on the economy and society may be greater than those of some armed attacks.[24][25] This term is closely related to the concept of the "grey zone", which came to prominence in 2017, describing hostile actions that fall below the traditional threshold of war.[26] But as Kello explained, technological unpeace differs from the grey zone as the term is commonly used in that unpeace by definition is never overtly violent or fatal, whereas some grey-zone actions are violent, even if they are not acts of war.[27]

Cyberwarfare vs. cyber war

The term "cyberwarfare" is distinct from the term "cyber war". Cyberwarfare includes techniques, tactics and procedures that may be involved in a cyber war, but the term does not imply scale, protraction or violence, which are typically associated with the term "war", which inherently refers to a large-scale action, typically over a protracted period of time, and may include objectives seeking to utilize violence or the aim to kill.[9] A cyber war could accurately describe a protracted period of back-and-forth cyber attacks (including in combination with traditional military action) between warring states. To date, no such action is known to have occurred. Instead, armed forces have responded with tit-for-tat military cyber actions. For example, in June 2019, the United States launched a cyber attack against Iranian weapons systems in retaliation to the shooting down of a US drone in the Strait of Hormuz.[28][29]

Cyberwarfare and cyber sanctions

In addition to retaliatory digital attacks, countries can respond to cyber attacks with cyber sanctions. Sometimes, it is not easy to detect the attacker, but suspicions may focus on a particular country or group of countries. In these cases, unilateral and multilateral economic sanctions can be used instead of cyberwarfare. For example, the United States has frequently imposed economic sanctions related to cyber attacks. Two Executive Orders issued during the Obama administration, EO 13694 of 2015[30] and EO 13757 of 2016,[31][32] specifically focused on the implementation of the cyber sanctions. Subsequent US presidents have issued similar Executive Orders. The US Congress has also imposed cyber sanctions in response to cyberwarfare. For example, the Iran Cyber Sanctions Act of 2016 imposes sanctions on specific individuals responsible for cyber attacks.[33]

Types of threat

Types of warfare

Cyber warfare can present a multitude of threats towards a nation. At the most basic level, cyber attacks can be used to support traditional warfare. For example, tampering with the operation of air defenses via cyber means in order to facilitate an air attack.[34] Aside from these "hard" threats, cyber warfare can also contribute towards "soft" threats such as espionage and propaganda. Eugene Kaspersky, founder of Kaspersky Lab, equates large-scale cyber weapons, such as Flame and NetTraveler which his company discovered, to biological weapons, claiming that in an interconnected world, they have the potential to be equally destructive.[20][35]

Espionage

Traditional espionage is not an act of war, nor is cyber-espionage, and both are generally assumed to be ongoing between major powers.[36] Despite this assumption, some incidents can cause serious tensions between nations, and are often described as "attacks". For example:[37]

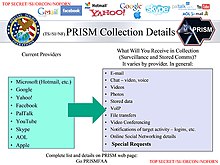

- Massive spying by the US on many countries, revealed by Edward Snowden.

- After the NSA's spying on Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel was revealed, the Chancellor compared the NSA with the Stasi.[38]

- The NSA recording nearly every cell phone conversation in the Bahamas, without the Bahamian government's permission, and similar programs in Kenya, the Philippines, Mexico and Afghanistan.[39][40]

- The "Titan Rain" probes of American defense contractors computer systems since 2003.[41]

- The Office of Personnel Management data breach, in the US, widely attributed to China.[42][43]

- The security firm Area 1 published details of a breach that compromised one of the European Union's diplomatic communication channels for three years.[44]

Out of all cyber attacks, 25% of them are espionage based.[45]

Sabotage

Computers and satellites that coordinate other activities are vulnerable components of a system and could lead to the disruption of equipment. Compromise of military systems, such as C4ISTAR components that are responsible for orders and communications could lead to their interception or malicious replacement. Power, water, fuel, communications, and transportation infrastructure all may be vulnerable to disruption. According to Clarke, the civilian realm is also at risk, noting that the security breaches have already gone beyond stolen credit card numbers, and that potential targets can also include the electric power grid, trains, or the stock market.[46]

In mid-July 2010, security experts discovered a malicious software program called Stuxnet that had infiltrated factory computers and had spread to plants around the world. It is considered "the first attack on critical industrial infrastructure that sits at the foundation of modern economies," notes The New York Times.[47]

Stuxnet, while extremely effective in delaying Iran's nuclear program for the development of nuclear weaponry, came at a high cost. For the first time, it became clear that not only could cyber weapons be defensive but they could be offensive. The large decentralization and scale of cyberspace makes it extremely difficult to direct from a policy perspective. Non-state actors can play as large a part in the cyberwar space as state actors, which leads to dangerous, sometimes disastrous, consequences. Small groups of highly skilled malware developers are able to as effectively impact global politics and cyber warfare as large governmental agencies. A major aspect of this ability lies in the willingness of these groups to share their exploits and developments on the web as a form of arms proliferation. This allows lesser hackers to become more proficient in creating the large scale attacks that once only a small handful were skillful enough to manage. In addition, thriving black markets for these kinds of cyber weapons are buying and selling these cyber capabilities to the highest bidder without regard for consequences.[48][49]

Denial-of-service attack

In computing, a denial-of-service attack (DoS attack) or distributed denial-of-service attack (DDoS attack) is an attempt to make a machine or network resource unavailable to its intended users. Perpetrators of DoS attacks typically target sites or services hosted on high-profile web servers such as banks, credit card payment gateways, and even root nameservers. DoS attacks often leverage internet-connected devices with vulnerable security measures to carry out these large-scale attacks.[50] DoS attacks may not be limited to computer-based methods, as strategic physical attacks against infrastructure can be just as devastating. For example, cutting undersea communication cables may severely cripple some regions and countries with regards to their information warfare ability.[51]

Electrical power grid

The federal government of the United States admits that the electric power grid is susceptible to cyberwarfare.[52][53] The United States Department of Homeland Security works with industries to identify vulnerabilities and to help industries enhance the security of control system networks. The federal government is also working to ensure that security is built in as the next generation of "smart grid" networks are developed.[54] In April 2009, reports surfaced that China and Russia had infiltrated the U.S. electrical grid and left behind software programs that could be used to disrupt the system, according to current and former national security officials.[55] The North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) has issued a public notice that warns that the electrical grid is not adequately protected from cyber attack.[56] China denies intruding into the U.S. electrical grid.[57] One countermeasure would be to disconnect the power grid from the Internet and run the net with droop speed control only.[58] Massive power outages caused by a cyber attack could disrupt the economy, distract from a simultaneous military attack, or create a national trauma.[59]

Iranian hackers, possibly Iranian Cyber Army pushed a massive power outage for 12 hours in 44 of 81 provinces of Turkey, impacting 40 million people. Istanbul and Ankara were among the places suffering blackout.[60]

Howard Schmidt, former Cyber-Security Coordinator of the US, commented on those possibilities:[21]

It's possible that hackers have gotten into administrative computer systems of utility companies, but says those aren't linked to the equipment controlling the grid, at least not in developed countries. [Schmidt] has never heard that the grid itself has been hacked.

In June 2019, Russia said that its electrical grid has been under cyber-attack by the United States. The New York Times reported that American hackers from the United States Cyber Command planted malware potentially capable of disrupting the Russian electrical grid.[61]

Propaganda

Cyber propaganda is an effort to control information in whatever form it takes, and influence public opinion.[62] It is a form of psychological warfare, except it uses social media, fake news websites and other digital means.[63] In 2018, Sir Nicholas Carter, Chief of the General Staff of the British Army stated that this kind of attack from actors such as Russia "is a form of system warfare that seeks to de-legitimize the political and social system on which our military strength is based".[64]

Jowell and O'Donnell (2006) state that "propaganda is the deliberate, systematic attempt to shape perceptions, manipulate cognitions, and direct behavior to achieve a response that furthers the desired intent of the propagandist" (p. 7). The internet is the most important means of communication today. People can convey their messages quickly across to a huge audience, and this can open a window for evil. Terrorist organizations can exploit this and may use this medium to brainwash people. It has been suggested that restricted media coverage of terrorist attacks would in turn decrease the number of terrorist attacks that occur afterwards.[65]

Economic disruption

In 2017, the WannaCry and Petya (NotPetya) cyber attacks, masquerading as ransomware, caused large-scale disruptions in Ukraine as well as to the U.K.'s National Health Service, pharmaceutical giant Merck, Maersk shipping company and other organizations around the world.[66][67][68] These attacks are also categorized as cybercrimes, specifically financial crime because they negatively affect a company or group.[69]

Surprise cyber attack

The idea of a "cyber Pearl Harbor" has been debated by scholars, drawing an analogy to the historical act of war.[70][71] Others have used "cyber 9/11" to draw attention to the nontraditional, asymmetric, or irregular aspect of cyber action against a state.[72][73]

Motivations

There are a number of reasons nations undertake offensive cyber operations. Sandro Gaycken, a cyber security expert and adviser to NATO, advocates that states take cyber warfare seriously as they are viewed as an attractive activity by many nations, in times of war and peace. Offensive cyber operations offer a large variety of cheap and risk-free options to weaken other countries and strengthen their own positions. Considered from a long-term, geostrategic perspective, cyber offensive operations can cripple whole economies, change political views, agitate conflicts within or among states, reduce their military efficiency and equalize the capacities of high-tech nations to that of low-tech nations, and use access to their critical infrastructures to blackmail them.[74]

Military

With the emergence of cyber as a substantial threat to national and global security, cyber war, warfare and/or attacks also became a domain of interest and purpose for the military.[75]

In the U.S., General Keith B. Alexander, first head of USCYBERCOM, told the Senate Armed Services Committee that computer network warfare is evolving so rapidly that there is a "mismatch between our technical capabilities to conduct operations and the governing laws and policies. Cyber Command is the newest global combatant and its sole mission is cyberspace, outside the traditional battlefields of land, sea, air and space." It will attempt to find and, when necessary, neutralize cyberattacks and to defend military computer networks.[76]

Alexander sketched out the broad battlefield envisioned for the computer warfare command, listing the kind of targets that his new headquarters could be ordered to attack, including "traditional battlefield prizes – command-and-control systems at military headquarters, air defense networks and weapons systems that require computers to operate."[76]

One cyber warfare scenario, Cyber-ShockWave, which was wargamed on the cabinet level by former administration officials, raised issues ranging from the National Guard to the power grid to the limits of statutory authority.[77][78][79][80]

The distributed nature of internet based attacks means that it is difficult to determine motivation and attacking party, meaning that it is unclear when a specific act should be considered an act of war.[81]

Examples of cyberwarfare driven by political motivations can be found worldwide. In 2008, Russia began a cyber attack on the Georgian government website, which was carried out along with Georgian military operations in South Ossetia. In 2008, Chinese "nationalist hackers" attacked CNN as it reported on Chinese repression on Tibet.[82] Hackers from Armenia and Azerbaijan have actively participated in cyberwarfare as part of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, with Azerbaijani hackers targeting Armenian websites and posting Ilham Aliyev's statements.[83][84]

Jobs in cyberwarfare have become increasingly popular in the military. All four branches of the United States military actively recruit for cyber warfare positions.[85]

In a 2024 study on the use of military cyber operations during the Russo-Ukrainian War, Frederik A. H. Pedersen and Jeppe T. Jacobsen concluded that cyber operations in warfare may only be impactful on the tactical and operational levels in a war's beginning, when cyber and non-cyber operations can be aligned and complex cyber weapons can be prepared before war breaks out, as well as cumulatively on a strategic level.[86]

Civil

Potential targets in internet sabotage include all aspects of the Internet from the backbones of the web, to the internet service providers, to the varying types of data communication mediums and network equipment. This would include: web servers, enterprise information systems, client server systems, communication links, network equipment, and the desktops and laptops in businesses and homes. Electrical grids, financial networks, and telecommunications systems are also deemed vulnerable, especially due to current trends in computerization and automation.[87]

Hacktivism

Politically motivated hacktivism involves the subversive use of computers and computer networks to promote an agenda, and can potentially extend to attacks, theft and virtual sabotage that could be seen as cyberwarfare – or mistaken for it.[88] Hacktivists use their knowledge and software tools to gain unauthorized access to computer systems they seek to manipulate or damage not for material gain or to cause widespread destruction, but to draw attention to their cause through well-publicized disruptions of select targets. Anonymous and other hacktivist groups are often portrayed in the media as cyber-terrorists, wreaking havoc by hacking websites, posting sensitive information about their victims, and threatening further attacks if their demands are not met. However, hacktivism is more than that. Actors are politically motivated to change the world, through the use of fundamentalism. Groups like Anonymous, however, have divided opinion with their methods.[89]

Income generation

Cyber attacks, including ransomware, can be used to generate income. States can use these techniques to generate significant sources of income, which can evade sanctions and perhaps while simultaneously harming adversaries (depending on targets). This tactic was observed in August 2019 when it was revealed North Korea had generated $2 billion to fund its weapons program, avoiding the blanket of sanctions levied by the United States, United Nations and the European Union.[90][91]

Private sector

Computer hacking represents a modern threat in ongoing global conflicts and industrial espionage and as such is presumed to widely occur.[87] It is typical that this type of crime is underreported to the extent they are known. According to McAfee's George Kurtz, corporations around the world face millions of cyberattacks a day. "Most of these attacks don't gain any media attention or lead to strong political statements by victims."[92] This type of crime is usually financially motivated.[93]

Non-profit research

But not all those who engage in cyberwarfare do so for financial or ideological reasons. There are institutes and companies like the University of Cincinnati[94] or the Kaspersky Security Lab which engage in cyberwarfare so as to better understand the field through actions like the researching and publishing of new security threats.[95]

Preparedness

A number of countries conduct exercise to increase preparedness and explore the strategy, tactics and operations involved in conducting and defending against cyber attacks against hostile states, this is typically done in the form of war games.[96]

The Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCE), part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), have conducted a yearly war game called Locked Shields since 2010 designed to test readiness and improve skills, strategy tactics and operational decision making of participating national organizations.[97][98] Locked Shields 2019 saw 1200 participants from 30 countries compete in a red team vs. blue team exercise. The war game involved a fictional country, Berylia, which was "experiencing a deteriorating security situation, where a number of hostile events coincide with coordinated cyber attacks against a major civilian internet service provider and maritime surveillance system. The attacks caused severe disruptions in the power generation and distribution, 4G communication systems, maritime surveillance, water purification plant and other critical infrastructure components". CCDCE describe the aim of the exercise was to "maintain the operation of various systems under intense pressure, the strategic part addresses the capability to understand the impact of decisions made at the strategic and policy level."[97][99] Ultimately, France was the winner of Locked Shields 2019.[100]

The European Union conducts cyber war game scenarios with member states and foreign partner states to improve readiness, skills and observe how strategic and tactical decisions may affect the scenario.[101]

As well as war games which serve a broader purpose to explore options and improve skills, cyber war games are targeted at preparing for specific threats. In 2018 the Sunday Times reported the UK government was conducting cyber war games which could "blackout Moscow".[102][103] These types of war games move beyond defensive preparedness, as previously described above and onto preparing offensive capabilities which can be used as deterrence, or for "war".[104]

Cyber activities by nation

Approximately 120 countries have been developing ways to use the Internet as a weapon and target financial markets, government computer systems and utilities.[105]

Asia

China

According to Fritz, China has expanded its cyber capabilities and military technology by acquiring foreign military technology.[106] Fritz states that the Chinese government uses "new space-based surveillance and intelligence gathering systems, Anti-satellite weapon, anti-radar, infrared decoys, and false target generators" to assist in this quest, and that they support their "Informatisation" of their military through "increased education of soldiers in cyber warfare; improving the information network for military training, and has built more virtual laboratories, digital libraries and digital campuses."[106] Through this informatisation, they hope to prepare their forces to engage in a different kind of warfare, against technically capable adversaries.[107] Foreign Policy magazine put the size of China's "hacker army" at anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000 individuals.[108] Diplomatic cables highlight US concerns that China is using access to Microsoft source code and 'harvesting the talents of its private sector' to boost its offensive and defensive capabilities.[109]

While China continues to be held responsible for a string of cyber-attacks on a number of public and private institutions in the United States, India, Russia, Canada, and France, the Chinese government denies any involvement in cyber-spying campaigns. The administration maintains the position that China is also victim to an increasing number of cyber-attacks. Most reports about China's cyber warfare capabilities have yet to be confirmed by the Chinese government.[110]

In June 2015, the United States Office of Personnel Management (OPM) announced that it had been the target of a data breach targeting the records of as many as four million people.[111] Later, FBI Director James Comey put the number at 18 million.[112] The Washington Post has reported that the attack originated in China, citing unnamed government officials.[113]

Operation Shady RAT is a series of cyber attacks starting mid-2006, reported by Internet security company McAfee in August 2011. China is widely believed to be the state actor behind these attacks which hit at least 72 organizations including governments and defense contractors.[114]

The 2018 cyberattack on the Marriott hotel chain[115][116] that collected personal details of roughly 500 million guests is now known to be a part of a Chinese intelligence-gathering effort that also hacked health insurers and the security clearance files of millions more Americans, The hackers, are suspected of working on behalf of the Ministry of State Security (MSS), the country's Communist-controlled civilian spy agency.[117][118][119]

On 14 September 2020, a database showing personal details of about 2.4 million people around the world was leaked and published. A Chinese company, Zhenhua Data compiled the database.[120] According to the information from "National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System", which is run by State Administration for Market Regulation in China, the shareholders of Zhenhua Data Information Technology Co., Ltd. are two natural persons and one general partnership enterprise whose partners are natural persons.[121] Wang Xuefeng, who is the chief executive and the shareholder of Zhenhua Data, has publicly boasted that he supports "hybrid warfare" through manipulation of public opinion and "psychological warfare".[122]

In February 2024 The Philippines announced that it had successfully fought off a cyber attack which was traced to hackers in China. Several government websites were targeted including the National coast watch and personal website of the president of the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos Jr.[123]

In May 2024 The UK announced that it had taken a database offline that is used by its defense ministry after coming under a cyber attack attributed to the Chinese state.[124]

India

The Department of Information Technology created the Indian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-In) in 2004 to thwart cyber attacks in India.[125] That year, there were 23 reported cyber security breaches. In 2011, there were 13,301. That year, the government created a new subdivision, the National Critical Information Infrastructure Protection Centre (NCIIPC) to thwart attacks against energy, transport, banking, telecom, defense, space and other sensitive areas.[126]

The executive director of the Nuclear Power Corporation of India (NPCIL) stated in February 2013 that his company alone was forced to block up to ten targeted attacks a day. CERT-In was left to protect less critical sectors.[127]

A high-profile cyber attack on 12 July 2012 breached the email accounts of about 12,000 people, including those of officials from the Ministry of External Affairs, Ministry of Home Affairs, Defense Research and Development Organizations (DRDO), and the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP).[125] A government-private sector plan being overseen by National Security Advisor (NSA) Shivshankar Menon began in October 2012, and intends to boost up India's cyber security capabilities in the light of a group of experts findings that India faces a 470,000 shortfall of such experts despite the country's reputation of being an IT and software powerhouse.[128]

In February 2013, Information Technology Secretary J. Satyanarayana stated that the NCIIPC[page needed] was finalizing policies related to national cyber security that would focus on domestic security solutions, reducing exposure through foreign technology.[125] Other steps include the isolation of various security agencies to ensure that a synchronised attack could not succeed on all fronts and the planned appointment of a National Cyber Security Coordinator. As of that month, there had been no significant economic or physical damage to India related to cyber attacks.

On 26 November 2010, a group calling itself the Indian Cyber Army hacked the websites belonging to the Pakistan Army and the others belong to different ministries, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Finance, Pakistan Computer Bureau, Council of Islamic Ideology, etc. The attack was done as a revenge for the Mumbai terrorist attacks.[129]

On 4 December 2010, a group calling itself the Pakistan Cyber Army hacked the website of India's top investigating agency, the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). The National Informatics Center (NIC) has begun an inquiry.[130]

In July 2016, Cymmetria researchers discovered and revealed the cyber attack dubbed 'Patchwork', which compromised an estimated 2500 corporate and government agencies using code stolen from GitHub and the dark web. Examples of weapons used are an exploit for the Sandworm vulnerability (CVE-2014–4114), a compiled AutoIt script, and UAC bypass code dubbed UACME. Targets are believed to be mainly military and political assignments around Southeast Asia and the South China Sea and the attackers are believed to be of Indian origin and gathering intelligence from influential parties.[131][132]

The Defence Cyber Agency, which is the Indian Military agency responsible for Cyberwarfare, is expected to become operational by November 2019.[133]

Philippines

The Chinese are being blamed after a cybersecurity company, F-Secure Labs, found a malware, NanHaiShu, which targeted the Philippines Department of Justice. It sent information in an infected machine to a server with a Chinese IP address. The malware which is considered particularly sophisticated in nature was introduced by phishing emails that were designed to look like they were coming from an authentic sources. The information sent is believed to be relating to the South China Sea legal case.[134]

South Korea

In July 2009, there were a series of coordinated denial of service attacks against major government, news media, and financial websites in South Korea and the United States.[135] While many thought the attack was directed by North Korea, one researcher traced the attacks to the United Kingdom.[136] Security researcher Chris Kubecka presented evidence multiple European Union and United Kingdom companies unwittingly helped attack South Korea due to a W32.Dozer infections, malware used in part of the attack. Some of the companies used in the attack were partially owned by several governments, further complicating cyber attribution.[137]

In July 2011, the South Korean company SK Communications was hacked, resulting in the theft of the personal details (including names, phone numbers, home and email addresses and resident registration numbers) of up to 35 million people. A trojaned software update was used to gain access to the SK Communications network. Links exist between this hack and other malicious activity and it is believed to be part of a broader, concerted hacking effort.[138]

With ongoing tensions on the Korean Peninsula, South Korea's defense ministry stated that South Korea was going to improve cyber-defense strategies in hopes of preparing itself from possible cyber attacks. In March 2013, South Korea's major banks – Shinhan Bank, Woori Bank and NongHyup Bank – as well as many broadcasting stations – KBS, YTN and MBC – were hacked and more than 30,000 computers were affected; it is one of the biggest attacks South Korea has faced in years.[139] Although it remains uncertain as to who was involved in this incident, there has been immediate assertions that North Korea is connected, as it threatened to attack South Korea's government institutions, major national banks and traditional newspapers numerous times – in reaction to the sanctions it received from nuclear testing and to the continuation of Foal Eagle, South Korea's annual joint military exercise with the United States. North Korea's cyber warfare capabilities raise the alarm for South Korea, as North Korea is increasing its manpower through military academies specializing in hacking. Current figures state that South Korea only has 400 units of specialized personnel, while North Korea has more than 3,000 highly trained hackers; this portrays a huge gap in cyber warfare capabilities and sends a message to South Korea that it has to step up and strengthen its Cyber Warfare Command forces. Therefore, in order to be prepared from future attacks, South Korea and the United States will discuss further about deterrence plans at the Security Consultative Meeting (SCM). At SCM, they plan on developing strategies that focuses on accelerating the deployment of ballistic missiles as well as fostering its defense shield program, known as the Korean Air and Missile Defense.[140]

North Korea

Africa

Egypt

In an extension of a bilateral dispute between Ethiopia and Egypt over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, Ethiopian government websites have been hacked by the Egypt-based hackers in June 2020.[141][142]

Europe

Cyprus

The New York Times published an exposé revealing an extensive three-year phishing campaign aimed against diplomats based in Cyprus. After accessing the state system the hackers had access to the European Union's entire exchange database.[143] By login into Coreu, hackers accessed communications linking all EU states, on both sensitive and not so sensitive matters. The event exposed poor protection of routine exchanges among European Union officials and a coordinated effort from a foreign entity to spy on another country. "After over a decade of experience countering Chinese cyberoperations and extensive technical analysis, there is no doubt this campaign is connected to the Chinese government", said Blake Darche, one of the Area 1 Security experts – the company revealing the stolen documents. The Chinese Embassy in the US did not return calls for comment.[144] In 2019, another coordinated effort took place that allowed hackers to gain access to government (gov.cy) emails. Cisco's Talos Security Department revealed that "Sea Turtle" hackers carried out a broad piracy campaign in the DNS countries, hitting 40 different organizations, including Cyprus.[145]

Estonia

In April 2007, Estonia came under cyber attack in the wake of relocation of the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn.[146] The largest part of the attacks were coming from Russia and from official servers of the authorities of Russia.[147] In the attack, ministries, banks, and media were targeted.[148][149] This attack on Estonia, a seemingly small Baltic state, was so effective because of how most of Estonian government services are run online. Estonia has implemented an e-government, where banking services, political elections, taxes, and other components of a modern society are now all done online.[150]

France

In 2013, the French Minister of Defense, Mr Jean-Yves Le Drian, ordered the creation of a cyber army, representing its fourth national army corps[151] (along with ground, naval and air forces) under the French Ministry of Defense, to protect French and European interests on its soil and abroad.[152] A contract was made with French firm EADS (Airbus) to identify and secure its main elements susceptible to cyber threats.[153] In 2016 France had planned 2600 "cyber-soldiers" and a 440 million euros investment for cybersecurity products for this new army corps.[154] An additional 4400 reservists constitute the heart of this army from 2019.[155]

Germany

In 2013, Germany revealed the existence of their 60-person Computer Network Operation unit.[156] The German intelligence agency, BND, announced it was seeking to hire 130 "hackers" for a new "cyber defence station" unit. In March 2013, BND president Gerhard Schindler announced that his agency had observed up to five attacks a day on government authorities, thought mainly to originate in China. He confirmed the attackers had so far only accessed data and expressed concern that the stolen information could be used as the basis of future sabotage attacks against arms manufacturers, telecommunications companies and government and military agencies.[157] Shortly after Edward Snowden leaked details of the U.S. National Security Agency's cyber surveillance system, German Interior Minister Hans-Peter Friedrich announced that the BND would be given an additional budget of 100 million Euros to increase their cyber surveillance capability from 5% of total internet traffic in Germany to 20% of total traffic, the maximum amount allowed by German law.[158]

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, Cyber Defense is nationally coordinated by the National Cyber Security Centrum (NCSC).[159] The Dutch Ministry of Defense laid out a cyber strategy in 2011.[160] The first focus is to improve the cyber defense handled by the Joint IT branch (JIVC). To improve intel operations, the intel community in the Netherlands (including the military intel organization, MIVD) has set up the Joint Sigint Cyber Unit (JSCU). The Ministry of Defense oversees an offensive cyber force, called Defensive Cyber Command (DCC).[161]

Norway

Russia

It has been claimed that Russian security services organized a number of denial of service attacks as a part of their cyber-warfare against other countries,[162] most notably the 2007 cyberattacks on Estonia and the 2008 cyberattacks on Russia, South Ossetia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan.[163] One identified young Russian hacker said that he was paid by Russian state security services to lead hacking attacks on NATO computers. He was studying computer sciences at the Department of the Defense of Information. His tuition was paid for by the FSB.[164] Russian, South Ossetian, Georgian and Azerbaijani sites were attacked by hackers during the 2008 South Ossetia War.[165]

In October 2016, Jeh Johnson the United States Secretary of Homeland Security and James Clapper the U.S. Director of National Intelligence issued a joint statement accusing Russia of interfering with the 2016 United States presidential election.[166] The New York Times reported the Obama administration formally accused Russia of stealing and disclosing Democratic National Committee emails.[167] Under U.S. law (50 U.S.C.Title 50 – War and National Defense, Chapter 15 – National Security, Subchapter III Accountability for Intelligence Activities[168]) there must be a formal Presidential finding prior to authorizing a covert attack. Then U.S. vice president Joe Biden said on the American news interview program Meet The Press that the United States will respond.[169] The New York Times noted that Biden's comment "seems to suggest that Mr. Obama is prepared to order – or has already ordered – some kind of covert action".[170]

Sweden

In January 2017, Sweden's armed forces were subjected to a cyber-attack that caused them to shutdown a so-called Caxcis IT system used in military exercises.[171]

Ukraine

According to CrowdStrike from 2014 to 2016, the Russian APT Fancy Bear used Android malware to target the Ukrainian Army's Rocket Forces and Artillery. They distributed an infected version of an Android app whose original purpose was to control targeting data for the D-30 Howitzer artillery. The app, used by Ukrainian officers, was loaded with the X-Agent spyware and posted online on military forums. The attack was claimed by Crowd-Strike to be successful, with more than 80% of Ukrainian D-30 Howitzers destroyed, the highest percentage loss of any artillery pieces in the army (a percentage that had never been previously reported and would mean the loss of nearly the entire arsenal of the biggest artillery piece of the Ukrainian Armed Forces[172]).[173] According to the Ukrainian army this number is incorrect and that losses in artillery weapons "were way below those reported" and that these losses "have nothing to do with the stated cause".[174]

In 2014, the Russians were suspected to use a cyber weapon called "Snake", or "Ouroboros," to conduct a cyber attack on Ukraine during a period of political turmoil. The Snake tool kit began spreading into Ukrainian computer systems in 2010. It performed Computer Network Exploitation (CNE), as well as highly sophisticated Computer Network Attacks (CNA).[175]

On 23 December 2015 the Black-Energy malware was used in a cyberattack on Ukraine's power-grid that left more than 200,000 people temporarily without power. A mining company and a large railway operator were also victims of the attack.[176]

Ukraine saw a massive surge in cyber attacks during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Several websites belonging to Ukrainian banks and government departments became inaccessible.[177]

United Kingdom

MI6 reportedly infiltrated an Al Qaeda website and replaced the instructions for making a pipe bomb with the recipe for making cupcakes.[178]

In October 2010, Iain Lobban, the director of the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), said the UK faces a "real and credible" threat from cyber attacks by hostile states and criminals and government systems are targeted 1,000 times each month, such attacks threatened the UK's economic future, and some countries were already using cyber assaults to put pressure on other nations.[179]

On 12 November 2013, financial organizations in London conducted cyber war games dubbed "Waking Shark 2"[180] to simulate massive internet-based attacks against bank and other financial organizations. The Waking Shark 2 cyber war games followed a similar exercise in Wall Street.[181]

Middle East

Iran

Iran has been both victim and perpetrator of several cyberwarfare operations. Iran is considered an emerging military power in the field.[182]

In September 2010, Iran was attacked by the Stuxnet worm, thought to specifically target its Natanz nuclear enrichment facility. It was a 500-kilobyte computer worm that infected at least 14 industrial sites in Iran, including the Natanz uranium-enrichment plant. Although the official authors of Stuxnet haven't been officially identified, Stuxnet is believed to be developed and deployed by the United States and Israel.[183] The worm is said to be the most advanced piece of malware ever discovered and significantly increases the profile of cyberwarfare.[184][185]

Iranian Cyber Police department, FATA, was dismissed one year after its creation in 2011 because of the arrest and death of Sattar Behesti, a blogger, in the custody of FATA. Since then, the main responsible institution for the cyberwarfare in Iran is the "Cyber Defense Command" operating under the Joint Staff of Iranian Armed Forces.

The Iranian state sponsored group MuddyWater is active since at least 2017 and is responsible for many cyber attacks on various sectors.[186]

Israel

In the 2006 war against Hezbollah, Israel alleges that cyber-warfare was part of the conflict, where the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) intelligence estimates several countries in the Middle East used Russian hackers and scientists to operate on their behalf. As a result, Israel attached growing importance to cyber-tactics, and became, along with the U.S., France and a couple of other nations, involved in cyber-war planning. Many international high-tech companies are now locating research and development operations in Israel, where local hires are often veterans of the IDF's elite computer units.[187] Richard A. Clarke adds that "our Israeli friends have learned a thing or two from the programs we have been working on for more than two decades."[14]: 8

In September 2007, Israel carried out an airstrike on a suspected nuclear reactor[188] in Syria dubbed Operation Orchard. U.S. industry and military sources speculated that the Israelis may have used cyberwarfare to allow their planes to pass undetected by radar into Syria.[189][190]

Following US President Donald Trump's decision to pull out of the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018, cyber warfare units in the United States and Israel monitoring internet traffic out of Iran noted a surge in retaliatory cyber attacks from Iran. Security firms warned that Iranian hackers were sending emails containing malware to diplomats who work in the foreign affairs offices of US allies and employees at telecommunications companies, trying to infiltrate their computer systems.[191]

Saudi Arabia

On 15 August 2012 at 11:08 am local time, the Shamoon virus began destroying over 35,000 computer systems, rendering them inoperable. The virus used to target the Saudi government by causing destruction to the state owned national oil company Saudi Aramco. The attackers posted a pastie on PasteBin.com hours prior to the wiper logic bomb occurring, citing oppression and the Al-Saud regime as a reason behind the attack.[192]

The attack was well staged according to Chris Kubecka, a former security advisor to Saudi Aramco after the attack and group leader of security for Aramco Overseas.[193] It was an unnamed Saudi Aramco employee on the Information Technology team which opened a malicious phishing email, allowing initial entry into the computer network around mid-2012.[194]

Kubecka also detailed in her Black Hat USA talk Saudi Aramco placed the majority of their security budget on the ICS control network, leaving the business network at risk for a major incident.[194] The virus has been noted to have behavior differing from other malware attacks, due to the destructive nature and the cost of the attack and recovery. US Defense Secretary Leon Panetta called the attack a "Cyber Pearl Harbor".[195] Shamoon can spread from an infected machine to other computers on the network. Once a system is infected, the virus continues to compile a list of files from specific locations on the system, upload them to the attacker, and erase them. Finally the virus overwrites the master boot record of the infected computer, making it unusable.[196][197] The virus has been used for cyber warfare against the national oil companies Saudi Aramco and Qatar's RasGas.[198][199][196][200]

Saudi Aramco announced the attack on their Facebook page and went offline again until a company statement was issued on 25 August 2012. The statement falsely reported normal business was resumed on 25 August 2012. However a Middle Eastern journalist leaked photographs taken on 1 September 2012 showing kilometers of petrol trucks unable to be loaded due to backed business systems still inoperable.

On 29 August 2012 the same attackers behind Shamoon posted another pastie on PasteBin.com, taunting Saudi Aramco with proof they still retained access to the company network. The post contained the username and password on security and network equipment and the new password for the CEO Khalid Al- Falih[201] The attackers also referenced a portion of the Shamoon malware as further proof in the pastie.[202]

According to Kubecka, in order to restore operations. Saudi Aramco used its large private fleet of aircraft and available funds to purchase much of the world's hard drives, driving the price up. New hard drives were required as quickly as possible so oil prices were not affected by speculation. By 1 September 2012 gasoline resources were dwindling for the public of Saudi Arabia 17 days after the 15 August attack. RasGas was also affected by a different variant, crippling them in a similar manner.[203]

Qatar

In March 2018 American Republican fundraiser Elliott Broidy filed a lawsuit against Qatar, alleging that Qatar's government stole and leaked his emails in order to discredit him because he was viewed "as an impediment to their plan to improve the country's standing in Washington."[204] In May 2018, the lawsuit named Mohammed bin Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, brother of the Emir of Qatar, and his associate Ahmed Al-Rumaihi, as allegedly orchestrating Qatar's cyber warfare campaign against Broidy.[205] Further litigation revealed that the same cybercriminals who targeted Broidy had targeted as many as 1,200 other individuals, some of whom are also "well-known enemies of Qatar" such as senior officials of the U.A.E., Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain. While these hackers almost always obscured their location, some of their activity was traced to a telecommunication network in Qatar.[206]

United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates has launched several cyber-attacks in the past targeting dissidents. Ahmed Mansoor, an Emirati citizen, was jailed for sharing his thoughts on Facebook and Twitter.[207] He was given the code name Egret under the state-led covert project called Raven, which spied on top political opponents, dissidents, and journalists. Project Raven deployed a secret hacking tool called Karma, to spy without requiring the target to engage with any web links.[208]

In September 2021, three of the former American intelligence officers, Marc Baier, Ryan Adams, and Daniel Gericke, admitted to assisting the UAE in hacking crimes by providing them with advanced technology and violating US laws. Under a three-year deferred prosecution agreement with the Justice Department, the three defendants also agreed to pay nearly $1.7 million in fines to evade prison sentences. The court documents revealed that the Emirates hacked into the computers and mobile phones of dissidents, activists, and journalists. They also attempted to break into the systems of the US and rest of the world.[209]

North America

United States

Cyberwarfare in the United States is a part of the American military strategy of proactive cyber defence and the use of cyberwarfare as a platform for attack.[210] The new United States military strategy makes explicit that a cyberattack is casus belli just as a traditional act of war.[211]

U.S. government security expert Richard A. Clarke, in his book Cyber War (May 2010), had defined "cyberwarfare" as "actions by a nation-state to penetrate another nation's computers or networks for the purposes of causing damage or disruption."[14]: 6 The Economist describes cyberspace as "the fifth domain of warfare,"[212] and William J. Lynn, U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense, states that "as a doctrinal matter, the Pentagon has formally recognized cyberspace as a new domain in warfare . . . [which] has become just as critical to military operations as land, sea, air, and space."[213]

When Russia was still a part of the Soviet Union in 1982, a portion of a Trans-Siberia pipeline within its territory exploded,[214] allegedly due to a Trojan Horse computer malware implanted in the pirated Canadian software by the Central Intelligence Agency. The malware caused the SCADA system running the pipeline to malfunction. The "Farewell Dossier" provided information on this attack, and wrote that compromised computer chips would become a part of Soviet military equipment, flawed turbines would be placed in the gas pipeline, and defective plans would disrupt the output of chemical plants and a tractor factory. This caused the "most monumental nonnuclear explosion and fire ever seen from space." However, the Soviet Union did not blame the United States for the attack.[215]

In 2009, president Barack Obama declared America's digital infrastructure to be a "strategic national asset," and in May 2010 the Pentagon set up its new U.S. Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM), headed by General Keith B. Alexander, director of the National Security Agency (NSA), to defend American military networks and attack other countries' systems. The EU has set up ENISA (European Union Agency for Network and Information Security) which is headed by Prof. Udo Helmbrecht and there are now further plans to significantly expand ENISA's capabilities. The United Kingdom has also set up a cyber-security and "operations centre" based in Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), the British equivalent of the NSA. In the U.S. however, Cyber Command is only set up to protect the military, whereas the government and corporate infrastructures are primarily the responsibility respectively of the Department of Homeland Security and private companies.[212]

On 19 June 2010, United States Senator Joe Lieberman (I-CT) introduced a bill called "Protecting Cyberspace as a National Asset Act of 2010",[216] which he co-wrote with Senator Susan Collins (R-ME) and Senator Thomas Carper (D-DE). If signed into law, this controversial bill, which the American media dubbed the "Kill switch bill", would grant the president emergency powers over parts of the Internet. However, all three co-authors of the bill issued a statement that instead, the bill "[narrowed] existing broad presidential authority to take over telecommunications networks".[217]

In August 2010, the U.S. for the first time warned publicly about the Chinese military's use of civilian computer experts in clandestine cyber attacks aimed at American companies and government agencies. The Pentagon also pointed to an alleged China-based computer spying network dubbed GhostNet which was revealed in a 2009 research report.[218][219]

On 6 October 2011, it was announced that Creech AFB's drone and Predator fleet's command and control data stream had been keylogged, resisting all attempts to reverse the exploit, for the past two weeks.[220] The Air Force issued a statement that the virus had "posed no threat to our operational mission".[221]

On 21 November 2011, it was widely reported in the U.S. media that a hacker had destroyed a water pump at the Curran-Gardner Township Public Water District in Illinois.[222] However, it later turned out that this information was not only false, but had been inappropriately leaked from the Illinois Statewide Terrorism and Intelligence Center.[223]

In June 2012 the New York Times reported that president Obama had ordered the cyber attack on Iranian nuclear enrichment facilities.[224]

In August 2012, USA Today reported that the US conducted cyberattacks for tactical advantage in Afghanistan.[225]

According to a 2013 Foreign Policy magazine article, NSA's Tailored Access Operations (TAO) unit "has successfully penetrated Chinese computer and telecommunications systems for almost 15 years, generating some of the best and most reliable intelligence information about what is going on inside the People's Republic of China."[226][227]

In 2014, Barack Obama ordered an intensification of cyberwarfare against North Korea's missile program for sabotaging test launches in their opening seconds.[228] On 24 November 2014, Sony Pictures Entertainment hack was a release of confidential data belonging to Sony Pictures Entertainment (SPE).

In 2016 President Barack Obama authorized the planting of cyber weapons in Russian infrastructure in the final weeks of his presidency in response to Moscow's interference in the 2016 presidential election.[229] On 29 December 2016 United States imposed the most extensive sanctions against Russia since the Cold War,[230] expelling 35 Russian diplomats from the United States.[231][232]

Economic sanctions are the most frequently used the foreign policy instruments by the United States today[233] Thus, it is not surprising to see that economic sanctions are also used as counter policies against cyberattacks. According to Onder (2021), economic sanctions are also information gathering mechanisms for the sanctioning states about the capabilities of the sanctioned states.[234]

In March 2017, WikiLeaks published more than 8,000 documents on the CIA. The confidential documents, codenamed Vault 7 and dated from 2013 to 2016, include details on CIA's software capabilities, such as the ability to compromise cars, smart TVs,[235] web browsers (including Google Chrome, Microsoft Edge, Mozilla Firefox, and Opera Software ASA),[236][237][238] and the operating systems of most smartphones (including Apple's iOS and Google's Android), as well as other operating systems such as Microsoft Windows, macOS, and Linux.[239]

In June 2019, the New York Times reported that American hackers from the United States Cyber Command planted malware potentially capable of disrupting the Russian electrical grid.[61]

The United States topped the world in terms of cyberwarfare intent and capability, according to Harvard University's Belfer Center Cyber 2022 Power Index, above China, Russia, the United Kingdom and Australia.[240]

In June 2023, the National Security Agency and Apple were accused by the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) of compromising thousands of iPhones, including those of diplomats from China, Israel, NATO members, and Syria. Kaspersky Lab said many of its senior staff and managers were also hit by the ongoing attack, which it first suspected in early 2023. The oldest traces of infiltration date back to 2019. Kaspersky Lab said it had not shared the findings with Russian authorities until the FSB announcement.[240]

Cyber mercenary

A cyber mercenary is a non-state actor that carries out cyber attacks for Nation states for hire. State actors can use the cyber mercenaries as a front to try and distance themselves from the attack with plausible deniability.[241]

Cyberpeace

The rise of cyber as a warfighting domain has led to efforts to determine how cyberspace can be used to foster peace. For example, the German civil rights panel FIfF runs a campaign for cyberpeace − for the control of cyberweapons and surveillance technology and against the militarization of cyberspace and the development and stockpiling of offensive exploits and malware.[242] Measures for cyberpeace include policymakers developing new rules and norms for warfare, individuals and organizations building new tools and secure infrastructures, promoting open source, the establishment of cyber security centers, auditing of critical infrastructure cybersecurity, obligations to disclose vulnerabilities, disarmament, defensive security strategies, decentralization, education and widely applying relevant tools and infrastructures, encryption and other cyberdefenses.[242][243]

The topics of cyber peacekeeping[244][245] and cyber peacemaking[246] have also been studied by researchers, as a way to restore and strengthen peace in the aftermath of both cyber and traditional warfare.[247]

Cyber counterintelligence

Cyber counter-intelligence are measures to identify, penetrate, or neutralize foreign operations that use cyber means as the primary tradecraft methodology, as well as foreign intelligence service collection efforts that use traditional methods to gauge cyber capabilities and intentions.[248]

- On 7 April 2009, The Pentagon announced they spent more than $100 million in the last six months responding to and repairing damage from cyber attacks and other computer network problems.[249]

- On 1 April 2009, U.S. lawmakers pushed for the appointment of a White House cyber security "czar" to dramatically escalate U.S. defenses against cyber attacks, crafting proposals that would empower the government to set and enforce security standards for private industry for the first time.[250]

- On 9 February 2009, the White House announced that it will conduct a review of the country's cyber security to ensure that the Federal government of the United States cyber security initiatives are appropriately integrated, resourced and coordinated with the United States Congress and the private sector.[251]

- In the wake of the 2007 cyberwar waged against Estonia, NATO established the Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCD CoE) in Tallinn, Estonia, in order to enhance the organization's cyber defence capability. The center was formally established on 14 May 2008, and it received full accreditation by NATO and attained the status of International Military Organization on 28 October 2008.[252] Since Estonia has led international efforts to fight cybercrime, the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation says it will permanently base a computer crime expert in Estonia in 2009 to help fight international threats against computer systems.[253]

- In 2015, the Department of Defense released an updated cyber strategy memorandum detailing the present and future tactics deployed in the service of defense against cyberwarfare. In this memorandum, three cybermissions are laid out. The first cybermission seeks to arm and maintain existing capabilities in the area of cyberspace, the second cybermission focuses on prevention of cyberwarfare, and the third cybermission includes strategies for retaliation and preemption (as distinguished from prevention).[254]

One of the hardest issues in cyber counterintelligence is the problem of cyber attribution. Unlike conventional warfare, figuring out who is behind an attack can be very difficult.[255]

Doubts about existence

In October 2011 the Journal of Strategic Studies, a leading journal in that field, published an article by Thomas Rid, "Cyber War Will Not Take Place" which argued that all politically motivated cyber attacks are merely sophisticated versions of sabotage, espionage, or subversion – and that it is unlikely that cyber war will occur in the future.[256]

Legal perspective

NIST, a cybersecurity framework, was published in 2014 in the US.[257]

The Tallinn Manual, published in 2013, is an academic, non-binding study on how international law, in particular the jus ad bellum and international humanitarian law, apply to cyber conflicts and cyber warfare. It was written at the invitation of the Tallinn-based NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence by an international group of approximately twenty experts between 2009 and 2012.[258]

The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (members of which include China and Russia) defines cyberwar to include dissemination of information "harmful to the spiritual, moral and cultural spheres of other states". In September 2011, these countries proposed to the UN Secretary General a document called "International code of conduct for information security".[259]

In contrast, the United approach focuses on physical and economic damage and injury, putting political concerns under freedom of speech. This difference of opinion has led to reluctance in the West to pursue global cyber arms control agreements.[260] However, American General Keith B. Alexander did endorse talks with Russia over a proposal to limit military attacks in cyberspace.[261] In June 2013, Barack Obama and Vladimir Putin agreed to install a secure Cyberwar-Hotline providing "a direct secure voice communications line between the US cybersecurity coordinator and the Russian deputy secretary of the security council, should there be a need to directly manage a crisis situation arising from an ICT security incident" (White House quote).[262]

A Ukrainian international law scholar, Alexander Merezhko, has developed a project called the International Convention on Prohibition of Cyberwar in Internet. According to this project, cyberwar is defined as the use of Internet and related technological means by one state against the political, economic, technological and information sovereignty and independence of another state. Professor Merezhko's project suggests that the Internet ought to remain free from warfare tactics and be treated as an international landmark. He states that the Internet (cyberspace) is a "common heritage of mankind".[263]

On the February 2017 RSA Conference Microsoft president Brad Smith suggested global rules – a "Digital Geneva Convention" – for cyber attacks that "ban the nation-state hacking of all the civilian aspects of our economic and political infrastructures". He also stated that an independent organization could investigate and publicly disclose evidence that attributes nation-state attacks to specific countries. Furthermore, he said that the technology sector should collectively and neutrally work together to protect Internet users and pledge to remain neutral in conflict and not aid governments in offensive activity and to adopt a coordinated disclosure process for software and hardware vulnerabilities.[264][265] A fact-binding body has also been proposed to regulate cyber operations.[266][267]

In popular culture

In films

- Independence Day (1996)

- Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines (2003)

- Live Free or Die Hard (2007)

- Terminator Genisys (2015)

- Snowden (2016)

- Terminator: Dark Fate (2019)

- Documentaries

- Hacking the Infrastructure: Cyber Warfare (2016) by Viceland

- Cyber War Threat (2015)

- Darknet, Hacker, Cyberwar[268] (2017)

- Zero Days (2016)

- The Perfect Weapon (2020)

In television

- "Cancelled", an episode of the animated sitcom South Park

- Series 2 of COBRA, a British thriller series, revolves around a sustained campaign of cyberwar against the United Kingdom and the British government's response to it.

See also

- Automated teller machine

- Computer security

- Computer security organizations

- Cyberattack

- Cybercrime

- Cyber spying

- Cyber-arms industry

- Cyber-collection

- Cyberterrorism

- Cyberweapon

- Duqu

- Fifth Dimension Operations

- IT risk

- iWar

- List of cyber attack threat trends

- List of cyber warfare forces

- List of cyberattacks

- Military-digital complex

- Penetration test

- Proactive cyber defence

- Signals intelligence

- Silent Horizon

- United States Cyber Command

- Virtual war

- Convention on Cybercrime

- Vulkan files leak

- Cyberattack

- Cybercrime

- Hacking

- DDoS

- Spyware

- Firewall

References

- ^ Singer, P. W.; Friedman, Allan (March 2014). Cybersecurity and cyberwar: what everyone needs to know. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-991809-6. OCLC 802324804.

- ^ "Cyberwar – does it exist?". NATO. 13 June 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Smith, Troy E. (2013). "Cyber Warfare: A Misrepresentation of the True Cyber Threat". American Intelligence Journal. 31 (1): 82–85. ISSN 0883-072X. JSTOR 26202046.

- ^ Lucas, George (2017). Ethics and Cyber Warfare: The Quest for Responsible Security in the Age of Digital Warfare. Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-19-027652-2.

- ^ "Advanced Persistent Threat Groups". FireEye. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ "APT trends report Q1 2019". securelist.com. 30 April 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ "GCHQ". www.gchq.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ "Who are the cyberwar superpowers?". World Economic Forum. 4 May 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Green, James A., ed. (7 November 2016). Cyber warfare: a multidisciplinary analysis. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-78707-9. OCLC 980939904.

- ^ Newman, Lily Hay (6 May 2019). "What Israel's Strike on Hamas Hackers Means For Cyberwar". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Liptak, Andrew (5 May 2019). "Israel launched an airstrike in response to a Hamas cyberattack". The Verge. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ a b Robinson, Michael; Jones, Kevin; Helge, Janicke (2015). "Cyber Warfare Issues and Challenges". Computers and Security. 49: 70–94. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2014.11.007. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ a b Shakarian, Paulo; Shakarian, Jana; Ruef, Andrew (2013). Introduction to cyber-warfare: a multidisciplinary approach. Amsterdam: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers – Elsevier. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-12-407926-7. OCLC 846492852.

- ^ a b c d Clarke, Richard A. Cyber War, HarperCollins (2010) ISBN 978-0-06-196223-3

- ^ Blitz, James (1 November 2011). "Security: A huge challenge from China, Russia and organised crime". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 6 June 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- ^ Arquilla, John (1999). "Can information warfare ever be just?". Ethics and Information Technology. 1 (3): 203–212. doi:10.1023/A:1010066528521. S2CID 29263858.

- ^ Parks, Raymond C.; Duggan, David P. (September 2011). "Principles of Cyberwarfare". IEEE Security Privacy. 9 (5): 30–35. doi:10.1109/MSP.2011.138. ISSN 1558-4046. S2CID 17374534.

- ^ Taddeo, Mariarosaria (19 July 2012). An analysis for a just cyber warfare. International Conference on Cyber Conflict (ICCC). Estonia: IEEE.

- ^ "Implications of Privacy & Security Research for the Upcoming Battlefield of Things". Journal of Information Warfare. 17 (4). 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Latest viruses could mean 'end of the world as we know it,' says the man who discovered Flame", The Times of Israel, 6 June 2012

- ^ a b "White House Cyber Czar: 'There Is No Cyberwar'". Wired, 4 March 2010

- ^ Deibert, Ron (2011). "Tracking the emerging arms race in cyberspace". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 67 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1177/0096340210393703. S2CID 218770788.

- ^ "What limits does the law of war impose on cyber attacks?". International Committee of the Red Cross. 28 June 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Kello, Lucas (2017). The Virtual Weapon and International Order. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0-300-22023-0.

- ^ "The Politics of Cyberspace: Grasping the Danger". The Economist. London. 26 August 2017.

- ^ Popp, George; Canna, Sarah (Winter 2016). "The Characterization and Conditions of the Gray Zone" (PDF). NSI, Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 September 2021.

- ^ Kello, Lucas (2022). Striking Back: The End of Peace in Cyberspace and How to Restore It. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-300-24668-1.

- ^ "US 'launched cyber-attack on Iran weapons systems'". BBC News. 23 June 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ Barnes, Julian E.; Gibbons-Neff, Thomas (22 June 2019). "U.S. Carried Out Cyberattacks on Iran". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ "Executive Order – "Blocking the Property of Certain Persons Engaging in Significant Malicious Cyber-Enabled Activities"". The White House. 1 April 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "Sanctions Programs and Country Information". U.S. Department of the Treasury. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "Cyber Sanctions". United States Department of State. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Ratcliffe, John (18 May 2016). "Text – H.R.5222 – 114th Congress (2015–2016): Iran Cyber Sanctions Act of 2016". United States Congress. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Weinberger, Sharon (4 October 2007). "How Israel Spoofed Syria's Air Defense System". Wired.

- ^ "Cyber espionage bug attacking Middle East, but Israel untouched — so far", The Times of Israel, 4 June 2013

- ^ "A Note on the Laws of War in Cyberspace" Archived 7 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine, James A. Lewis, April 2010

- ^ "Cyberwarfare". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Rayman, Noah (18 December 2013). "Merkel Compared NSA To Stasi in Complaint To Obama". Time. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ^ Devereaux, Ryan; Greenwald, Glenn; Poitras, Laura (19 May 2014). "Data Pirates of the Caribbean: The NSA Is Recording Every Cell Phone Call in the Bahamas". The Intercept. First Look Media. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ^ Schonfeld, Zach (23 May 2014). "The Intercept Wouldn't Reveal a Country the U.S. Is Spying On, So WikiLeaks Did Instead". Newsweek. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ Bodmer, Kilger, Carpenter, & Jones (2012). Reverse Deception: Organized Cyber Threat Counter-Exploitation. New York: McGraw-Hill Osborne Media. ISBN 0-07-177249-9, ISBN 978-0-07-177249-5

- ^ Sanders, Sam (4 June 2015). "Massive Data Breach Puts 4 Million Federal Employees' Records at Risk". NPR. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Liptak, Kevin (4 June 2015). "U.S. government hacked; feds think China is the culprit". CNN. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Liptak, Kevin (20 June 2015). "Hacking Diplomatic Cables Is Expected. Exposing Them Is Not". Wired. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Gupta, S.C. (8 November 2022). 151 Essays. Vol. 1. Australia. p. 231.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Clarke: More defense needed in cyberspace" Archived 24 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine HometownAnnapolis.com, 24 September 2010

- ^ "Malware Hits Computerized Industrial Equipment". The New York Times, 24 September 2010

- ^ Singer, P.W.; Friedman, Allan (2014). Cybersecurity and Cyberwar: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-19-991809-6.

- ^ Gross, Michael L.; Canetti, Daphna; Vashdi, Dana R. (2016). "The psychological effects of cyber terrorism". The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 72 (5): 284–291. Bibcode:2016BuAtS..72e.284G. doi:10.1080/00963402.2016.1216502. ISSN 0096-3402. PMC 5370589. PMID 28366962.

- ^ "Understanding Denial-of-Service Attacks | CISA". us-cert.cisa.gov. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ Sherryn Groch; Felicity Lewis (4 November 2022). "The internet is run under the sea. What if the cables are cut?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Shiels, Maggie. (9 April 2009) BBC: Spies 'infiltrate US power grid'. BBC News. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Meserve, Jeanne (8 April 2009). "Hackers reportedly have embedded code in power grid". CNN. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "US concerned power grid vulnerable to cyber-attack" Archived 30 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine. In.reuters.com (9 April 2009). Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Gorman, Siobhan. (8 April 2009) Electricity Grid in U.S. Penetrated By Spies. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ NERC Public Notice. (PDF). Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Xinhua: China denies intruding into the U.S. electrical grid. 9 April 2009

- ^ ABC News: Video. ABC News. (20 April 2009). Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Buchan, Russell (2012). "Cyber Attacks: Unlawful Uses of Force or Prohibited Interventions?". Journal of Conflict and Security Law. 17 (2): 211–227. doi:10.1093/jcsl/krs014. ISSN 1467-7954. JSTOR 26296227.

- ^ Halpern, Micah (22 April 2015). "Iran Flexes Its Power by Transporting Turkey to the Stone Age". Observer.

- ^ a b "How Not To Prevent a Cyberwar With Russia". Wired. 18 June 2019.

- ^ "Russian military admits significant cyber-war effort". bbc.com. 21 February 2017.

- ^ Ajir, Media; Vailliant, Bethany (2018). "Russian Information Warfare: Implications for Deterrence Theory". Strategic Studies Quarterly. 12 (3): 70–89. ISSN 1936-1815. JSTOR 26481910.

- ^ Carter, Nicholas (22 January 2018). "Dynamic Security Threats and the British Army". RUSI. Archived from the original on 29 March 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ Cowen, Tyler (2006). "Terrorism as Theater: Analysis and Policy Implications". Public Choice. 128 (1/2): 233–244. doi:10.1007/s11127-006-9051-y. ISSN 0048-5829. JSTOR 30026642. S2CID 155001568.

- ^ "NotPetya: virus behind global attack 'masquerades' as ransomware but could be more dangerous, researchers warn". 28 June 2017. Archived from the original on 19 September 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ "NotPetya ransomware outbreak cost Merck more than $300M per quarter". TechRepublic. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ Perlroth, Nicole; Scott, Mark; Frenkel, Sheera (27 June 2017). "Cyberattack Hits Ukraine Then Spreads Internationally". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

- ^ Elhais, Hassan Elhais-Dr Hassan (21 November 2021). "What is the impact of ransomware on financial crime compliance in the UAE?". Lexology. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Palmer, Robert Kenneth. "Critical Infrastructure: Legislative Factors for Preventing a Cyber-Pearl Harbor." Va. JL & Tech. 18 (2013): 289.