Europa Europa

| Europa Europa | |

|---|---|

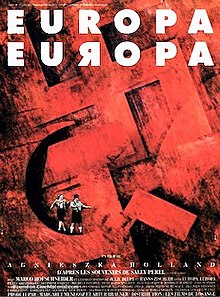

French theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Agnieszka Holland |

| Screenplay by | Agnieszka Holland |

| Based on | I Was Hitler Youth Salomon by Solomon Perel |

| Produced by | Artur Brauner Margaret Ménégoz |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Jacek Petrycki |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Zbigniew Preisner |

| Distributed by | Orion Pictures (US) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Countries | |

| Languages | German Russian Polish Hebrew Yiddish |

| Box office | $5,575,738 (domestic)[4] |

Europa Europa (German: Hitlerjunge Salomon, lit., "Hitler Youth Salomon") is a 1990 historical war drama film directed by Agnieszka Holland, and starring Marco Hofschneider, Julie Delpy, Hanns Zischler, and André Wilms. It is based on the 1989 autobiography of Solomon Perel, a German-Jewish boy who escaped the Holocaust by masquerading as a Nazi and joining the Hitler Youth. Perel himself appears briefly as "himself" in the film's finale. The film's title refers to World War II's division of continental Europe, resulting in a constant national shift of allegiances, identities, and front lines.

The film is an international co-production between the German company CCC Film and companies in France and Poland. Europa Europa won the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay in 1992.

Plot

In 1938, in Nazi Germany, on the eve of thirteen-year-old Solomon "Solek" Perel's bar mitzvah, Kristallnacht occurs. Solek evades the Nazis and later learns that his sister has been murdered. His father decides the family will move to his birthplace of Łódź in Poland, believing it will be safer there. Less than a year later, World War II begins, and Germany invades Poland. Solek's family decides he and his brother Isaak should flee to Eastern Europe. The brothers head for the eastern border of Poland, only to learn the Soviets have invaded. The brothers are separated, and Solek ends up in a Soviet orphanage in Grodno with other Polish refugee children.

Solek lives in the orphanage for two years, where he joins the Komsomol, receives a communist education, and learns Russian. He takes a romantic interest in Inna, a young instructor who defends him when the authorities discover his class origin is bourgeois. Solek receives a letter from his parents informing him of their imprisonment in the Łódź Ghetto.

Solek is captured by German soldiers during the German invasion of the Soviet Union and finds himself amongst Soviet prisoners. As the Germans single out the Jews and commissars for execution, Solek hides his identity papers and tells the Germans he is "Josef Peters", a "Volksdeutscher" from Grodno.[a] The soldiers believe Josef's parents were ethnic German, and he was in the orphanage because his parents were killed by the Soviets. Using his German-Russian bilingual language skill, "Josef" helps the unit identify a prisoner as Yakov Dzhugashvili, Joseph Stalin's son. The unit is impressed and adopts Solek as their interpreter, due to his fluency in German and Russian.

Solek avoids any public bathing or urinating, as his circumcised penis would expose him as a Jew. A closeted homosexual German soldier named Robert discovers Solek's secret but shows solidarity and sympathizes with him as they share a common ground of being in danger of persecution due to their backgrounds. During combat, Robert is killed, and Solek, the lone survivor of his unit, attempts to reach the Soviets. As he crosses a bridge, German soldiers charge across behind him, and the Soviet troops surrender; Solek is hailed as a hero. The company commander decides to adopt Solek and send him to the elite Hitler Youth Academy in Braunschweig, to receive a Nazi education.

At the school, Solek is very careful to hide his circumcision. Leni, a member of the Bund Deutscher Mädel who serves meals at the Academy, becomes infatuated with Solek. He returns her affections, but does not consummate their relationship for fear of exposing himself.

During his leave from the Academy, Solek travels to Łódź to find his family; however, the ghetto is sealed off and guarded. Solek rides a tram that travels through the ghetto, observing sights of tortured and starved people. Later, Solek visits Leni's mother, who does not sympathize with the Nazis. She tells him Leni is pregnant by Solek's roommate, Gerd, and will give up the child to the Lebensborn program. When Leni's mother presses Josef on his identity, he breaks down and confesses he is Jewish; she promises not to betray him.

Solek is summoned to the Gestapo offices. There, he is prodded about his supposed parentage and is asked to show a "Certificate of Racial Purity". When Solek claims the certificate is in Grodno, the Gestapo official says he will send for it. As Solek leaves to meet with Gerd, the building is destroyed by Allied bombs; Solek survives while Gerd dies in the bombing.

As Soviet troops close in on Berlin, the Hitler Youth are sent to the front lines. Solek deserts his unit and surrenders to the Soviets. His captors doubt that he is a Jew and accuse him of being a traitor. There, Solek learns of the Nazi death camps. The Soviets are about to have him shot when Solek's brother Isaak, just released from a camp, recognizes Solek. Isaak reveals their parents were killed years prior when the Łódź Ghetto was "liquidated". Shortly thereafter, Solek emigrates to the British Mandate of Palestine.

The real Solomon Perel, seen in modern day, sings as the film fades to a close.

Cast

- Marco Hofschneider as Solomon "Solek" Perel

- André Wilms as Robert Kellerman, a gay soldier who promises to protect Solek after discovering his Jewish identity

- Julie Delpy as Leni

- René Hofschneider as Isaak Perel

- Piotr Kozłowski as David Perel

- Klaus Abramowsky as Solomon's father

- Michèle Gleizer as Solomon's mother

- Ashley Wanninger as Gerd

- Nathalie Schmidt as Basia

- Delphine Forest as Inna Moyseevna

- Halina Łabonarska as Leni's mother

- Marta Sandrowicz as Bertha Perel

- Andrzej Mastalerz as Zenek Dracz

- Hanns Zischler as Hauptmann von Larenau

- Włodzimierz Press as Yakov Dzhugashvili, Stalin's son

- Martin Maria Blau as Ulmayer

- Solomon Perel as himself

Release

Box office

The film was given a limited release in the United States on 28 June 1991, and grossed $31,433 in its opening weekend in two theaters. Its final international gross was US$5,575,738.[4]

Reception

Europa Europa received widespread acclaim from critics. Europa Europa has an approval rating of 95% on review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 21 reviews, and an average rating of 7.8/10. [6]

Writing for the Los Angeles Times, critic Michael Wilmington lauded the film's multi-faceted structure, calling Europa Europa "a tense suspense story, an ironic romance, and a truly black comedy — all driving toward a dark crisis of identity".[7]

In a positive review, Janet Maslin of The New York Times said it "accomplishes what every film about the Holocaust seeks to achieve: It brings new immediacy to the outrage by locating specific, wrenching details that transcend cliche".[8]

Hal Hinson, of The Washington Post, praised the direction, saying "Holland isn't a dour moral instructor; she's an ironist with a deft ability to capture the absurd aspects of her material and keep them in balance with the tragic".[9] Hinson commended the film for its "[awareness] of the toll [Solly's] shape-shifting compromises exacts".[9] Desson Howe, also of The Post, was more critical, citing the film's "emotional distance",[10] and, similarly to Maslin, said the film did not fully probe Solly's conscience.[10]

Best Foreign Film controversy

As it won four major "best foreign-language film" prizes from American critics' groups of the 1991 awards season, Europa Europa was strongly regarded as a contender for a Best Foreign Film Oscar for the 64th Academy Awards ceremony.[7] However, the German Export Film Union, which oversaw the Oscar selection committee for German films, declined to submit the film for a nomination.[11] The committee reasoned the film did not meet certain eligibility criteria, such as not qualifying as a German film.[7][11] However, the film was a co-production between Germany, Poland, and France;[7] in addition, much of the film is spoken in German, while the film's producer and much of the cast and crew is German.[11] Export committee members reportedly called the film "junk" and "an embarrassment".[11][12] The film's unconventional use of black comedy, as opposed to full tragedy, in a Holocaust film has been speculated to be a main cause for the committee's omission.[13][14][15] The omission prompted leading German film-makers to write a public letter of support for the film and its director, Agnieszka Holland.[16][17] The letter signees included Werner Herzog, Wolfgang Petersen, and Wim Wenders.[7][16]

Despite the film's omission, it went on to be a critical and commercial success in the United States,[7] where it became the second most successful German film, after 1981's Das Boot,[16] and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay.[18]

Accolades

Home media

The film was released on DVD by MGM Home Entertainment on 4 March 2003.[27] The Criterion Collection released a special edition Blu-ray of the film on 9 July 2019.[28]

Notes

- ^ Horodno, a city in Belarus, formerly Poland-Lithuania.[5]

References

- ^ a b "Hitlerjunge Salomon". filmportal.de (in German). Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "Europa Europa". British Film Institute. London: BFI Film & Television Database. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "Europa Europa". Bifi.fr (in French). Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ a b Europa Europa at Box Office Mojo

- ^ "Grodno". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2024-03-04.

- ^ "Europa, Europa", Rotten Tomatoes, retrieved 2022-12-12

- ^ a b c d e f Wilmington, Michael (18 February 1992). ""Europa" at Center of Oscar Storm: Commentary: Debate over why the film won't be a foreign-language nominee reveals inequities of process". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (28 June 1991). "Reviews/Film; A Boy Confronts His Jewish Heritage as a Hero of Hitler Youth". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ a b Hinson, Hal (9 August 1991). "'Europa Europa'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ a b Howe, Desson (9 August 1991). "'Europa Europa'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d Weinraub, Bernard (14 January 1992). "The Talk of Hollywood; "Europa" Surfaces in Oscar Angling". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Fisher, Marc (20 February 1992). "A MESSAGE ON "EUROPA"". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ Iannone, Pasquale (October 2011). "Europa Europa". Senses of Cinema. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Taubin, Amy (9 July 2019). "Europa Europa: Border States". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Hornaday, Ann (5 December 1993). "FILM; For Foreign Films, the Rules For an Oscar Are Set in Sand". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Weinraub, Bernard (28 January 1992). "German Film-Makers Express Support for "Europa"". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (29 January 1992). "Germany Divided on "Europa": Movies: German film-makers protest the German Export Film Union's decision not to enter "Europa Europa" for best foreign-language film in the Academy Awards". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ a b "The 64th Academy Awards (1992) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ "BSFC Winners: 1990s". Boston Society of Film Critics. 27 July 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1993". BAFTA. 1993. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Europa Europa – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "KCFCC Award Winners – 1990-99". kcfcc.org. 14 December 2013. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "The Annual 17th Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "1991 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. 19 December 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1991 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". Mubi. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Europa Europa DVD". Amazon. 4 March 2003. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ Lybarger, Dan (26 July 2019). "Europa Europa deserving of its Criterion status". Arkansas Democrat-Gazette. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

External links

- Europa Europa at IMDb

- Europa Europa at Rotten Tomatoes

- Europa Europa: Border States an essay by Amy Taubin at the Criterion Collection

- A Life Stranger Than the Movie, 'Europa, Europa,' Based on It an interview with Solomon Perel