Paradise Now

| Paradise Now | |

|---|---|

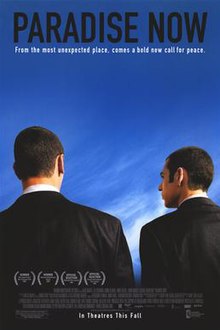

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Hany Abu-Assad |

| Written by | Hany Abu-Assad Bero Beyer Pierre Hodgson |

| Produced by | Bero Beyer |

| Starring | Kais Nashef Ali Suliman Lubna Azabal Hiam Abbass |

| Cinematography | Antoine Héberlé |

| Edited by | Sander Vos |

| Music by | Jina Sumedi |

| Distributed by | A-Film Distribution (Netherlands)[1] Constantin Film (Germany and Austria)[1] Haut et Court (France)[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Countries | Netherlands Palestine Germany France |

| Languages | Palestinian Arabic English |

| Budget | $2,000,000 |

| Box office | $3,579,902[2] |

Paradise Now (Arabic: الجنّة الآن, romanized: al-Janna al-Laan) is a 2005 psychological drama film directed by Hany Abu-Assad. It follows the story of two Palestinian men preparing for a suicide attack in Israel. The film won the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film and received an Academy Award nomination in the same category.

According to Abu-Assad, "The film is an artistic point of view of that political issue. The politicians want to see it as black and white, good and evil, and art wants to see it as a human thing."[3]

Plot

Paradise Now follows Palestinian childhood friends Said and Khaled who live in Nablus and have been recruited for suicide attacks in Tel Aviv. It focuses on what would be their last days together.

Their handlers from an unidentified terrorist group tell them the attack will take place the next day. The pair record videos glorifying God and their cause, and bid their unknowing families and loved ones goodbye, while trying to behave normally to avoid arousing suspicion. The next day, they shave off their hair and beards and don suits in order to look like Israelis. Their cover story is that they are going to a wedding.

An explosive belt is attached to each man; the handlers are the only ones with the keys needed to remove the belts without detonating them. The men are instructed to detonate the bombs at the same place, a military checkpoint in Israel, with a time interval of 15 minutes so that the second bomb will kill police arriving after the first blast.

They cross the Israeli border but have to flee from guards. Khaled returns to their handlers, who fled by the time Said arrives. The handlers remove Khaled's explosive belt and issue a search for Said. Khaled believes he is the best person to find Said since he knows him well, and he is given until the end of that day to find him.

After Said escapes from the guards, he approaches an Israeli settlement. At one point, he considers detonating the bomb on a commercial bus, but he decides not to when he sees a child on board. Eventually, Said reveals his reason for taking part in the suicide bombing. While in a car with Suha (Lubna Azabal), a woman he has fallen in love with, he explains that his father was an ameel (a "collaborator", or Palestinian working for the Israelis), who was executed for his actions. He blames the Israelis for taking advantage of his father's weakness.

Khaled eventually finds Said, who is still wearing the belt and about to detonate it while lying on his father's grave. They return to the handlers, and Said convinces them that the attack need not be canceled, because he is ready for it. They both travel to Tel Aviv. Influenced by Suha, who discovered their plan, Khaled cancels his suicide attack. Khaled tries to convince Said to back off as well. However, Said manages to shake Khaled by pretending to agree.

The film ends with a long shot of Said sitting on a bus carrying Israeli soldiers, slowly zooming in on his eyes, and then suddenly cuts to white.

Cast

- Kais Nashef as Said

- Ali Suliman as Khaled

- Lubna Azabal as Suha

- Hiam Abbass as Said's mother

Production

Hany Abu-Assad and co-writer Bero Beyer started working on the script in 1999, but it took them five years to get the story before cameras. The original script was about a man searching for his friend, who is a suicide bomber, but it evolved into a story of two friends, Said and Khaled.

The filmmakers faced great difficulties making the film on location. A land mine exploded 300 meters away from the set.[4] While filming in Nablus, Israeli helicopter gunships launched a missile attack on a car near the film's set one day, prompting six crew members to leave the production indefinitely.[5] Paradise Now's location manager was kidnapped by a Palestinian faction during the shooting and was not released until Palestinian president Yasser Arafat's office intervened.[4] In an interview with the Telegraph, Hany Abu-Assad said, "If I could go back in time, I wouldn't do it again. It's not worth endangering your life for a movie."[6]

Statements by the filmmakers

In Hany Abu-Assad's Golden Globe acceptance speech he made a plea for a Palestinian state, saying he hoped the Golden Globe was “a recognition that the Palestinians deserve their liberty and equality unconditionally."[7]

In an interview with Jewish American Tikkun magazine, Hany Abu-Assad was asked, "When you look ahead now, what gives you hope?", "The conscience of the Jewish people," he answered. "The Jews have been the conscience of humanity, always, wherever they go. Not all Jews, but part of them. Ethics. Morality. They invented it! I think Hitler wanted to kill the conscience of the Jews, the conscience of humanity. But this conscience is still alive.… Maybe a bit weak.… But still alive. Thank God."[8] In an interview with the Tel Aviv-based newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth, Abu-Assad stated he views Palestinian suicide attacks as counter-terrorism, and that had he been raised in the Palestinian territories instead of in his Arab-Israeli home city of Nazareth, he would have become a suicide bomber himself.[9]

Israeli-Jewish producer Amir Harel[10] told reporters that "First and foremost the movie is a good work of art", adding that "If the movie raises awareness or presents a different side of reality, this is an important thing."[11]

Oscar controversy

Paradise Now was the first Palestinian film to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. An earlier Palestinian film, Divine Intervention (2002), had controversially failed to gain admission to the competition, allegedly because films nominated for this award must be put forward by the government of their country, and Palestine's status as a sovereign state is disputed.This is similar to the sovereign state of Taiwan. Although Taiwan is a sovereign state, China often files complaints with organizations that recognize its sovereignty. Hong Kong is another special case. Despite being a Special Administrative Region of China it is allowed to make submissions as its own category. Puerto Rico too, enjoys a similar ability to submit entries even though it does not have full United Nations representation, which was used as a basis to launch accusations of a double standard.[citation needed]

Paradise Now was submitted to the academy and to the Golden Globes as a film from 'Palestine'. It was referred to as such at the Golden Globes. However, Israeli officials, including Consul General Ehud Danoch and Consul for Media and Public Affairs Gilad Millo, tried to extract a guarantee from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences that Paradise Now would not be presented in the ceremony as representing the state of Palestine, despite the fact it was introduced as such in the Academy Awards' official website.[12] The Academy Awards began to refer to the film's country instead as "the Palestinian Authority". This decision angered director-writer Hany Abu-Assad, who said it represented a slap in the face for the Palestinian people and their national identity. The academy subsequently referred to it as a submission from the "Palestinian Territories".[13]

On March 1, 2006, a group representing Israeli victims of suicide bombings asked the Oscar organizers to disqualify the film. These protesters claimed that showing the film was immoral and encouraged killing civilians in terror acts.[14]

Reception

Critical response

Paradise Now has an 89% rating on the review compendium website Rotten Tomatoes, based on 103 reviews, and an average rating of 7.48/10. The site's consensus states: "This film delves deeply into the minds of suicide bombers, and the result is unsettling."[15] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 71 out of 100, based on 32 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[16]

Stephen Holden, in his October 28, 2005 article in the New York Times, applauded the suspense and plot twists in the film, and the risks involved in humanizing suicide bombers, saying "it is easier to see a suicide bomber as a 21st-century Manchurian Candidate - a soulless, robotic shell of a person programmed to wreak destruction - than it is to picture a flesh-and-blood human being doing the damage."[17] In contrast, in a February 7, 2006 article for Ynetnews entitled "Anti-Semitism Now", Irit Linor criticized the movie as a "quality Nazi film".[18]

Accolades

Academy Award

- On January 31, 2006, the film was nominated in the Best Foreign Language Film category.

Golden Globe

- Paradise Now won "Best Foreign Language Film" for the 63rd Golden Globe Awards, the first time a Palestinian film was nominated for such an award.

Other awards won

- 2005 Berlin International Film Festival:

- Amnesty International Film Prize

- AGICOA 2005 Blue Angel Award

- Reader Jury of the "Berliner Morgenpost"

- 2005 European Film Awards:

- Best Screenplay

- 2005 Independent Spirit Awards:

- Best Foreign Film

- 2005 National Board of Review Awards (USA) :

- Best Foreign Language Film

- 2005 Netherlands Film Festival:

- Best Feature Film (Beste Lange Speelfilm)

- Best Editing (Beste Montage)

- 2005 Durban International Film Festival (South Africa)

- Best Director[19]

- 2005 Dallas-Fort Worth Film Critics Association Awards

- Best Foreign Language Film

- 2005 Vancouver Film Critics Circle Awards

- Best Foreign Film

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c "Film #23881: Paradise Now". Lumiere. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Paradise Now (2005)". Box Office Mojo.

- ^ Glaister, Dan. "It was a joke I was even nominated", The Guardian, January 20, 2006.

- ^ a b Garcia, Maria (20 October 2005). "Visions of Paradise". Film Journal International. Archived from the original on 12 December 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ [dead link] ae.philly.com

- ^ "I risked my life to make this movie". The Telegraph. London. 2006-07-28. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2018-07-27.

- ^ "Palestinian Film on Suicide Bombers Wins Golden Globe". Haaretz. Los Angeles. Reuters. 17 January 2006. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ "n Conversation: Paradise Now Director Hany Abu-Assad | Tikkun Magazine". Tikkun.org. 2007-10-11. Archived from the original on 2011-11-24. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ^ Hofstein, Avner (2 March 2006). "Oscar nominee: People hate Israelis for a reason". Ynetnews.com. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ Gutman, Matthew Suicide bomber story contender for foreign Oscar USA Today. 2 March 2006

- ^ Daraghmeh, Ali (2006-01-25). "Palestinians living in West Bank have dim view of "Paradise Now"". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2011-05-24. Retrieved 2019-03-06.

- ^ Dünya Namaz Vakitleri. "zaman.com". zaman.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ^ Agassi, Tirzah (26 February 2006). "Middle East tensions hang over Palestinian nominee for an Oscar / 'Paradise Now' traces lives of two men who are suicide bombers". SFGate.com. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ Toth, Sara (1 March 2006). "Some Israelis against 'Paradise Now'". The Mercury News. Jerusalem. Associated Press. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- ^ "Paradise Now". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ^ "Paradise Now".

- ^ Holden, Stephen (2005-10-28). "Terrorists Facing Their Moment of Truth". nytimes.com. Retrieved 2012-10-28.

- ^ Linor, Irit (7 February 2006). "Anti-Semitism now". ynetnews.com. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ "Durban International Film Festival Awards 2005". Centre for Creative Arts (South Africa). 22 May 2005. Archived from the original on 4 July 2005. Retrieved 6 March 2019.

- Greer, Darroch (December 1, 2005). "Fade to Black: Hany Abu-Assad, Director". digitalcontentproducer.com (Creative Planet Network). Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2016.