Judiciary of Italy

| Part of the Politics series |

|

|---|

|

|

The judiciary of Italy is composed of courts that interpret and apply the law in the Italian Republic. Magistracy is a public office, accessible by the sole Italian citizens who have obtained an Italian Juris Doctor and taken part to the relevant competitive public examination organised by the Ministry of justice. The judicial power is independent and there is no internal hierarchy within. Italian magistrates are either judges or public prosecutors.

In particular, the Italian judiciary is independent from the executive branch, which cannot interfere with the appointment, career advancement and the prerogatives of magistrates.[1] Once one accesses the magistracy, they serve so long as the maximum age for retirement eligibility is attained; disciplinary sanctions can be solely pronounced by the High Council of the Judiciary.

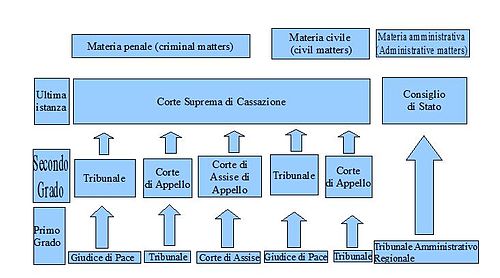

The structure of the Italian judiciary is three-tiered and follows the general civil law principles. Inferior courts have original and general jurisdiction over civil and criminal disputes. Appellate courts hear cases on appeal from lower courts, reassessing the legal principles used and, if need be, facts. The Corte Suprema di Cassazione is Italy's highest court in civil and criminal matters, and can be seized for matters relating to the interpretation of the law, exclusive of fact-related disputes.[2] Whilst the doctrine of stare decisis is not provided for under Italian law, the Corte Suprema di Cassazione's rulings exert legal suasion over lower courts.[3]

The administrative judicial circuit is independent from others powers under Article 120 of the Constitution, and also separate from the so-called ordinary judicial circuit wherein are comprised civil and criminal courts.[4] Administrative courts are divided into regional administrative courts and the Consiglio di Stato which sits as supreme court for administrative matters. The Managing Board of the administrative justice, instituted by ordinary law no. 205/2000, solves all issues related to the organisation, the functioning and the discipline of the administrative magistracy.

Law

The Italian legal system is based on civil law, even though, in certain instances, judicial rulings can be binding, and the rule of law. The laws of Italy rely on several sources, arranged in hierarchical scale so that lower rules cannot contradict upper rules.

The Italian Constitution signed in 1948 is the main legal source, which sets out the Republican form of the State, the separation of powers and the parliementary form of government.[5]

Italy's statutory laws comprise both codes and punctual statutes. Italy possesses a civil code which, originally, codified Roman law and was influenced by the German BGB and, slightly, by the Napoleonic civil code. The first code was adopted in 1865 under the Savoia's monarchy and then repealed by the second code of 1942, adopted during Fascism.[5] Likewise, the Italian penal code (also known as the "Rocco Code", eponym of the then Ministry of justice) was adopted in 1930 under the fascist regime.

Both the civil code and the penal code have undergone legislative modifications to ensure compliance with the democratic principle laid down, in the aftermath of World War II, by the Constitution and the corresponding social changes.[5]

Constitutional principles

Under Article 104 of the Constitution of the Italian Republic,[6] the judiciary is an autonomous branch of the State whose province is the interpretation and the application of the laws of the Italian Republic.

Once appointed to a certain office, judges and public prosecutors are irremovable by law unless the magistrate's consent or following a decision of the High Council of the Judiciary under one of the limitative reasons set out by the law.[7] In order to sanction an Italian magistrate, the prosecuting body must ensure compliance with the due process of law clause.

The High Council of the Judiciary is the self-governing body of the Italian judiciary, an institution of constitutional importance, chaired by the President of the Italian Republic and vice-chaired by a magistrate who ensures, de facto, presidency.[8] Article 105 of the Constitution vests this institution with the power to guarantee the autonomy and independence of the Italian judiciary, let alone solve any issue related to the recruitment, assignments and transfers, promotions and disciplinary measures vis-à-vis magistrates.[8]

The Constitution further lays down a number of principle that contribute to define the prerogatives of the Italian judiciary. First, judges must be preconstituted prior trial under Article 25, meaning that judges cannot be specially assigned to preside over a particular dispute. In the same vein, Article 102 § 2 prohibits the setting-up of extraordinary or special tribunals.[9]

Within the Italian legal order, magistrates are only subject to the law pursuant to Article 101 of the Constitution. Accordingly, neither the other powers of the States nor other courts' rulings can affect a magistrate's own decision-making process, as only legal norms of at least statutory relevance bind the magistrate's course of action. The independency of magistracy also involves absence of hierarchy among magistrates, who can only be distinguished by the functions vested in them pursuant to Article 107 § 3.[10]

The Italian judiciary disposes of the Italian judicial police.[11]

Legal status

General provisions

Public prosecutors and judges assigned to criminal bench are granted by law a license to carry firearms.[12]

Components

Career magistrates – also known as togates (togati) – can occupy one of the following offices:[13]

- ordinary court magistrate, who can serve as:

- public prosecutor; or,

- bench judges;

- administrative court magistrate, whose competence comprises the protection of legitimate interests against the public administration and specific matters arising out of the exercice of subjective rights;

- audit court magistrates assigned to the Court of Audit, with competence to assess and ascertain matters related to the public expenditure, let alone sanction those who have misused public funds; these magistrate can carry the duties of:

- public prosecutor; or,

- bench judges.

- tax court magistrate with jurisdiction over tax-related disputes.

However, access to each of the four main categories of public office is differentiated. Article 106 of the Constitution only requires the organisation of a public examination to provide for the appointment of magistrates. In fact, candidates with no prior legal experience can solely have access to ordinary courts via the public examination organised roughly each year by the Ministry of justice, whereas access to administrative, audit and tax courts requires separate competitions with relevant legal experience.

To complement these offices, Article 106 § 2 allows the High Council of the Judiciary to create punctual offices of councilor of cassation (consigliere di cassazione) in favour of university professors of law or lawyers with at least 15 years of experience and admitted to plead before the higher jurisdictions who have proven outstanding abilities throughtout their career.[14] These magistrates operate within the Corte Suprema di Cassazione.

Lastly, the Italian judiciary comprises honorary magistrate, who back professional magistrates in handling the workload that stems from less significant disputes. Litigation in Italy is known to bring about significant delays prior one can obtain a ruling, that is the so-called Italian torpedo. Honorary magistrates can either be assigned to a Court of peace (giudice di pace, for civil matters), to a honorary deputy public prosecutor office or to a honorary court (for criminal matters).[15] The adjective "honorary" is intended to confirm the non-professional nature of the duties carried out by these magistrates, who are remunerated according to the number of cases adjudged rather than on a fixed basis.[16]

The Italian military judiciary exists on a stand-alone basis, with exclusive competence to judge crimes committed by members of the Italian Armed Forces.[17]

Responsibility

Magistrates judges and prosecutors are liable under criminal, civil and disciplinary laws for the actions undertaken to the detriment of citizens through exercise of their functions; the principle of public liability of judges is rooted in Article 28 of the Constitution, that reads "the officials and employees of the State and public bodies are directly responsible, according to criminal, civil and administrative laws, for acts committed in violation of rights".[18] In such cases it extends to the State and public bodies.[18]

Personnel

Recruitment

Access to the ordinary magistrature, is based on a competitive examination managed by the Ministry of Justice. Candidates are required to possess an Italian law degree.[19]

Prior to the 2022 reform, candidates were required to pass the Italian bar examination and practice law for at least five years in the absence of any disciplinary sanction. Candidates could also rely on alternative requirements to qualify for the competitive assessment, namely:[20]

- graduation from the so-called Italian Schools of Specialization for the Legal Professions;

- obtention of Doctor of Philosophy in law;

- hold a position as university lecturer in legal matters in the absence of any disciplinary sanction;

- work within the Italian honorary magistrature for at least six years without demerit, revocation or disciplinary sanctions;

- work as C-category civil servant in the Italian administration with at least five years of seniority and absent any disciplinary sanction;

- completion of an eighteen-month internship within the judicial branch,[21] whether with a bench judge or a state's prosecutor;[22]

- hold a position of administrative or accounting magistrate;

- hold a position of state attorney (not to be confused with state prosecutors) in the absence of any disciplinary sanction.

The competitive examination is roughly held every every year and consists of three written compositions (first phase) followed by an oral examination (second phase). Candidates have to draft legal dissertations each eight-hour long, on a given subject of private law, criminal law and administrative law respectively. Upon obtention of the pass mark (12/20), they move on to the oral phase which substantiates in an interdisciplinary interview with the examination jury on the following subject-matters:[23]

- Roman law;

- civil law;

- civil procedure;

- criminal law;

- administrative law;

- constitutional law;

- tax law;

- commercial law;

- bankruptcy law;

- labor law;

- social security law;

- European Union law;

- public international law and private international law;

- elements of legal information technology and the Italian judicial system;

- interview on a foreign language, indicated by the candidate when applying for participation in the competition, chosen from: English, Spanish, French or German.

Laureates acquire the status of "trainee ordinary magistrate", following the reform of 2007 maintained by the last reform of 2022. Candidates can sit to the examination thrice in their life.[24]

Training and updating

The following training activities are provided for ordinary magistrates:[25]

- "initial training" (for trainee ordinary magistrates);

- "permanent training" for professional judges (implemented nationally and locally)

- training for office managers;

- "permanent training" for honorary magistrates (implemented nationally and locally);

- "International training".

A so-called "lifelong learning", previously carried out by the CSM (IX Commission),[26] from autumn 2012 gradually passed to the Higher School of the Judiciary. The inauguration of the training activities at the single site of Villa Castel Pulci in Scandicci (Florence) took place on 15 October 2012.[27]

Judicial stream

The Italian judiciary is the system of courts that adjudicates legal disputes/disagreements and interprets, defends, and applies the civil law, the criminal law and the administrative law in legal cases.

The structure of the Italian judiciary is divided into three tiers (gradi, sing. grado): primo grado ("first tier"), secondo grado ("second tier") and ultima istanza ("last resort") also called terzo grado ("third tier"). Inferior courts of original and general jurisdiction, intermediate appellate courts which hear cases on appeal from lower courts, and courts of last resort which hear appeals from lower appellate courts on the interpretation of law.[28]

Giudice di pace

The giudice di pace ("justice of the peace") is the court of original jurisdiction for less significant civil matters. The court replaced the old preture ("Praetor Courts") and the giudice conciliatore ("judge of conciliation") in 1991.[29]

Tribunale

The tribunale ("tribunal") is the court of general jurisdiction for civil matters. Here, litigants are statutorily required to be represented by an Italian barrister, or avvocato. It can be composed of one judge or of three judges, according to the importance of the case.[30] When acting as Appellate Court for the Justice of the Peace, it is always monocratico (composed of only one Judge).[30]

Divisions and Specialized Divisions

- Giudice del Lavoro ("labor tribunal"): hears disputes and suits between employers and employees (apart from cases dealt with in administrative courts, see below). A single judge presides over cases in the giudice del lavoro tribunal.[31]

- Sezione specializzata agraria ("land estate court"): the specialized section that hears all agrarian controversies. Cases in this court are heard by two expert members in agricultural matters.[32]

- Tribunale per i minorenni ("Family Proceedings Court"): the specialized section that hears all cases concerning minors, such as adoptions or emancipations; it is presided over by two professional judges and two lay judges.[33]

Corte d'appello

The Corte d'appello ("Court of Appeal") has jurisdiction to retry the cases heard by the tribunale as a Court of first instance and is divided into three or more divisions: labor, civil, and criminal.[34] Its jurisdiction is limited to a territorial constituency called a "district".[34] The judgments of the court of appeal can be appealed with a Supreme Court of Cassation appeal.[34]

Corte Suprema di Cassazione

The Corte Suprema di Cassazione ("Supreme Court of Cassation") is the highest court of appeal or court of last resort in Italy. It has its seat in the Palace of Justice, Rome. The Court of Cassation also ensures the correct application of law in the inferior and appeal courts and resolves disputes as to which lower court (penal, civil, administrative, military) has jurisdiction to hear a given case.[35]

Corte d'Assise

The Corte d'Assise ("Court of Assizes") has jurisdiction to try all crimes carrying a maximum penalty of 24 years in prison or more.[36] These are the most serious crimes, such as terrorism and murder. Also slavery, killing a consenting human being, and helping a person to commit suicide are serious crimes that are tried by this court. Penalties imposed by the court can include life sentences (ergastolo).[36]

Corte d'assise e d'appello

The Corte d'assise e d'appello ("Court of Assize Appeal") judges following an appeal against the sentences issued in the first instance by the assize court or by the judge of the preliminary hearing who has judged in the forms of the summary judgment on crimes whose knowledge is normally devolved to the court of assizes.[37] An appeal is made to the Supreme Court of Cassation against its sentences. The Court of Assize Appeal is made up of two professional judges and eight lay judges.[38]

Tribunale amministrativo regionale

The tribunale amministrativo regionale ("Regional administrative court") is competent to judge appeals, brought against administrative acts, by subjects who consider themselves harmed (in a way that does not comply with the legal system) in their own legitimate interest. These are administrative judges of first instance, whose sentences are appealable before the Council of State. For the same reason, it is the only type of special judiciary to provide for only two tiers of judgment.[39]

Consiglio di Stato

The Consiglio di Stato ("Council of State") is, in the Italian legal system, a body of constitutional significance. Provided for by art. 100 of the Constitution, which places it among the auxiliary organs of the government, it is a judicial body, and is also the highest special administrative judge, in a position of third party with respect to the Italian public administration, pursuant to art. 103 of the Constitution.[40]

Ministry of Justice

The Ministry of Justice handles the administration of courts and judiciary, including paying salaries and constructing new courthouses. The Ministry of Justice and that of the Infrastructure fund, and the Ministry of Justice and that of the Interior administer the prison system.

Lastly, the Ministry of Justice receives and processes applications for presidential pardons and proposes legislation dealing with matters of civil or criminal justice.[41]

Police forces

Penitentiary police

The polizia penitenziaria ("penitentiary police") is a law enforcement agency in Italy which is subordinate to the Ministry of Justice and operates the Italian prison system as corrections officers. The Vatican City, an independent state, does not have a prison system, so the Vatican sends convicted criminals to the Italian prison system.[42] According to Interpol, this force (as part of the Ministry of Justice) has a "nationwide remit for prison security, inmate safety and transportation".[43]

The polizia penitenziaria carries out the functions of the Judicial Police, Public Safety, Traffic Police and Corrections. They support other law enforcement agencies, such as with traffic roadblocks (known as a controllo).[44] The polizia penitenziaria is one of the four national police forces of Italy (along with the Carabinieri, the Polizia di Stato and the Guardia di Finanza), with each force performing a slightly different function.[45]

Judicial police

The polizia giudiziaria ("judicial police"), in Italy, indicates a civil service, exercised by subjects belonging to the Italian police forces and by certain officials of the Italian public administration; in the latter case in the cases expressly provided for by law. According to art. 109 of the Constitution of the Italian Republic, the Italian judicial authority directly disposes of the judicial police.[46] They exist primarily to provide evidence to the prosecutor. They can arrest and interrogate suspects, conduct lineups, question witnesses, and even interrogate non-suspects.[47]

See also

References

- ^ "Autonomia ed indipendenza della magistratura" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Il ricorso per cassazione. L'impugnazione per i soli vizi di applicazione della legge. Il terzo grado di Giudizio" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Case Law: il diritto del precedente". Altalex (in Italian). 19 October 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ admin. "Status e carriere dei giudici amministrativi". Amministrativisti Veneti (in Italian). Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ a b c "Guide to Law Online: Italy | Law Library of Congress". loc.gov.

- ^ "Art. 104 della Costituzione della Repubblica Italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Circolare CSM 30 novembre 1993, n. 15098" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Consiglio superiore della magistratura" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Art. 102 della Costituzione della Repubblica Italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "La Costituzione - Articolo 107 | Senato della Repubblica". www.senato.it. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ "Art. 109 della Costituzione della Repubblica Italiana" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Art. 73 R.D. 6 maggio 1940 n. 635" (in Italian). Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "Come diventare magistrato: percorso di studi, concorso, opportunità" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "La costituzione italiana – Articolo 106" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Riforma organica della magistratura onoraria e altre disposizioni sui giudici di pace" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "le figure della magistratura onoraria" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "OHCHR, The Italian Judicial System" (PDF).

- ^ a b "La Costituzione – Articolo 28" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "NUOVO ACCESSO DIRETTO AL CONCORSO IN MAGISTRATURA CON LA SOLA LAUREA – RIFORMA CARTABIA 2022 – ART 4 LEGGE 17 GIUGNO 2022, N. 71, n. 98" (in Italian). Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "Descrizione del concorso sul sito del Consiglio Superiore della Magistratura" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Art. 73 del decreto legge 21 giugno 2013, n. 69 – convertito in legge 9 agosto 2013, n. 98" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Art. 50 decreto legge 24 giugno 2014, n. 90 convertito in legge 11 agosto 2014, n. 114" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Come funziona concorso in magistratura" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Art. 1 paragraph 3 law 30 July 2007 n. 111.

- ^ "Sito della Scuola superiore della magistratura" (in Italian). Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Competenze della IX Commissione sul sito del Consiglio superiore della magistratura" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 27 April 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Scuola superiore della magistratura, "Inizio delle attività didattiche"" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Il ricorso per cassazione. L'impugnazione per i soli vizi di applicazione della legge. Il terzo grado di Giudizio" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Legge n. 374/1991" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Tribunale" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "A cosa serve il giudice del lavoro?" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Processo agrario" (in Italian). Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "N. 601 ORDINANZA (Atto di promovimento) 6 luglio 1993" (in Italian). Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "L'esordio operativo dell'Ufficio per il processo nelle Corti di appello" (in Italian). Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "La Corte di Cassazione" (in Italian). Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Competenza della corte di assise" (in Italian). Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "Concentrato di Procedura Penale" (PDF) (in Italian). p. 12. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "Nomina Giudice Popolare di Corte di Assise" (in Italian). Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "Gradi del giudizio amministrativo" (in Italian). Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "La Costituzione – Articolo 103" (in Italian). Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "Riforma della giustizia penale: contesto, obiettivi e linee di fondo della "legge Cartabia"" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Is the Vatican a Rogue State?" Spiegel Online. 19 January 2007. Retrieved on 25 August 2010.

- ^ "Italie". Interpol. 1 March 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ "Polizia Penitenziaria website page". poliziapenitenziaria.gov.it. Italian Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "I corpi armati in Italia" (in Italian). Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ "La Costituzione – Articolo 109" (in Italian).

- ^ "ORGANIZATION AND RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE ITALIAN JUDICIAL POLICE | Office of Justice Programs". ojp.gov. Retrieved 26 January 2022.