Old Assyrian period

Old Assyrian period ālu Aššur | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2025 BC–c. 1364 BC[a] | |||||||||

| Capital | Assur[b] | ||||||||

| Common languages | Akkadian, Sumerian and Amorite | ||||||||

| Religion | Ancient Mesopotamian religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Notable kings | |||||||||

• c. 2025 BC | Puzur-Ashur I (first) | ||||||||

• c. 1974–1935 BC | Erishum I | ||||||||

• c. 1920–1881 BC | Sargon I | ||||||||

• c. 1808–1776 BC | Shamshi-Adad I | ||||||||

• c. 1700–1691 BC | Bel-bani | ||||||||

• c. 1521–1498 BC | Puzur-Ashur III | ||||||||

• c. 1390–1364 BC | Eriba-Adad I (last) | ||||||||

| Legislature | Ālum | ||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||

• Assur becomes independent from the Third Dynasty of Ur | c. 2025 BC | ||||||||

• Conquest by Shamshi-Adad I | c. 1808 BC | ||||||||

• Collapse of Shamshi-Adad's kingdom | c. 1776–1765 BC | ||||||||

• Foundation of the Adaside dynasty | c. 1700 BC | ||||||||

• Subjugation under Mitanni | c. 1430–1360 BC | ||||||||

• End of the reign of Eriba-Adad I | c. 1364 BC[a] | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Iraq | ||||||||

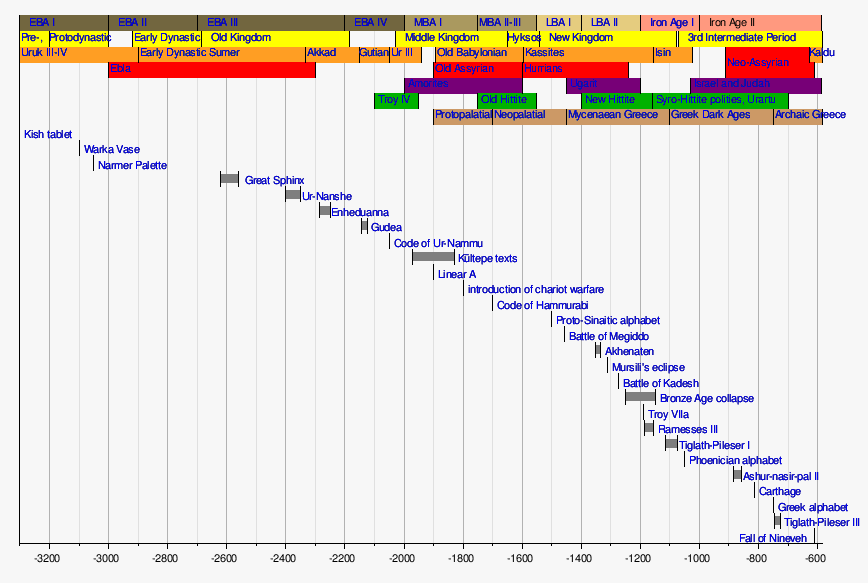

| Periodization of ancient Assyria | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||

|

See also: History of the Assyrians |

The Old Assyrian period was the second stage of Assyrian history, covering the history of the city of Assur from its rise as an independent city-state under Puzur-Ashur I c. 2025 BC[c] to the foundation of a larger Assyrian territorial state after the accession of Ashur-uballit I c. 1363 BC,[d] which marks the beginning of the succeeding Middle Assyrian period. The Old Assyrian period is marked by the earliest known evidence of the development of a distinct Assyrian culture, separate from that of southern Mesopotamia[7][8] and was a geopolitically turbulent time when Assur several times fell under the control or suzerainty of foreign kingdoms and empires. The period is also marked with the emergence of a distinct Assyrian dialect of the Akkadian language, a native Assyrian calendar and Assur for a time becoming a prominent site for international trade.[9]

For most of the Old Assyrian period, Assur was a minor city-state with little political and military influence. In contrast to Assyrian kings of later periods, the kings in the Old Assyrian period were just one of the prominent leading officials in the city's administration and normally used the style Išši'ak Aššur, which translates to "governor (on behalf) of (the god) Ashur", rather than šar (king). The kings presided over the city's actual administrative body, the Ālum (city assembly), which was made up of prominent and influential members among Assur's populace.[10] Though lacking in military and political might, Assur was an important economic center in northern Mesopotamia. From the time of Erishum I (c. 1974–1935 BC) until the late 19th century BC, the city was a hub in a large trading network that spanned from the Zagros Mountains in the east to central Anatolia in the west. During their time as prominent traders the Assyrians founded a number of trading colonies at various sites in the trading network, such as Kültepe.

The first Assyrian royal dynasty, founded by Puzur-Ashur I c. 2025 BC came to an end when the city was captured by the foreign Amorite conqueror Shamshi Adad I in c. 1808 BC. Shamshi-Adad ruled from the city Shubat-Enlil and established a short-lived kingdom, sometimes called the Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia, that collapsed after his death in c. 1776 BC. Events after Shamshi-Adad's death until the beginning of the Middle Assyrian period are poorly known, but there appears to initially have been some decades of frequent conflict in Assur and the surrounding region, not only between different states and empires, such as the Old Babylonian Empire, Mari and Eshnunna, but also between different Assyrian dynasties and nobles who vied for power over the city. This period culminated in the re-establishment of Assur as an independent city-state under the Adaside dynasty c. 1700 BC. Assur became a vassal of the Mitanni kingdom c. 1430 BC but broke free in the early 14th century after Mitanni suffered a series of defeats by the Hittites and began its transition into a large territorial state under a series of warrior-kings.

Through extensive cuneiform records, amounting to over 22,000 clay tablets found at the Old Assyrian trading colony at Kültepe, much information can be gathered about the culture, language and society of the Old Assyrian period. As in other societies of the Ancient Near East, the Old Assyrians practiced slavery, though confusion resulting from the terminology used in the texts might mean that many, but not all, of the supposed slaves were actually free servants.[11] Though men and women had different duties and responsibilities, they had more or less the same legal rights, with both being allowed to inherit property, make wills, initiate divorce proceedings and participate in trade.[12] The chief deity worshipped in the Old Assyrian period was, like in later periods, the Assyrian national deity Ashur, who had probably originated in the preceding Early Assyrian period as a deified personification of the city of Assur itself.[13]

Terminology

Modern researchers divide the thousands of years of ancient Assyrian history into several stages based on political events and gradual changes in language.[14] "Old Assyrian" is one of these stages and is thus a chronological label. As defined by Klaas Veenhof in 2008, the term applies to "the earliest phase of the culture of ancient Assur that is historically sufficiently recoverable to be called Assyrian", "Assyrian" here meaning the city of Assur and its culture rather than Assyria as a state governing a stretch of territory; Assyria only transitioned from a small city-state to a kingdom governing a larger stretch of territory in the succeeding Middle Assyrian period. As such, "Old Assyrian" refers to the history, politics, economics, religion, language and distinctive features of Assur and its people from the earliest comprehensive historical records at the site to the beginning of the Middle Assyrian period. Assur was much older than the commonly used beginning date for the Old Assyrian period, though the preceding Early Assyrian period is much more poorly known and Assur was not independent during that time but instead part of a sequence of states and empires from southern Mesopotamia.[7]

History

Puzur-Ashur and his dynasty

Assur is generally thought to have become an independent city-state under Puzur-Ashur I, who ruled c. 2025 BC.[15][16][17][18] Little is otherwise known of Puzur-Ashur, and it is unclear how exactly he came to power,[19] though his descendants, Assyria's first royal dynasty, wrote that he had restored the walls around the city.[20] Assur's independence was likely achieved in conjunction with the last Ur III ruler, Ibbi-Sin (c. 2028–2004 BC), losing his administrative grip on the peripheral regions of his empire.[21] Very little archaeological evidence survives from Assur in the first half of the second millennium BC and as a result, relatively little is known about the city, its people and its rulers during this time.[22] Surviving royal inscriptions from this time deal almost exclusively with building projects.[23] What is known is that Puzur-Ashur and his successors after independence did not actually claim the dignity of being kings (šar), as the Akkadian and Sumerian suzerains had done, but instead continued to style themselves as governors (Išši'ak), asserting that the Assyrian national god Ashur was king and that the Assyrian rulers therefore were only his representatives on Earth.[20][24] Assur was during the time of Puzur-Ashur's dynasty home to only about 5,000 to 8,000 people, which means its military power must have been very limited, and there are no sources that indicate any military institutions whatsoever. No surrounding cities were subjected to Assur and there are not even any known records of political interactions with the rulers of the city's immediate neighbors.[25]

The earliest known surviving inscription by an Assyrian king was written by Puzur-Ashur's son and successor Shalim-ahum, and records the king having built a temple dedicated to Ashur "for his own life and the life of his city".[20] Shalim-ahum's son and successor Ilu-shuma is the earliest Assyrian king known to have intervened in foreign affairs, campaigning and opening up trade. In one of his inscriptions, Ilu-shuma claims to have opened trade with the "Akkadians [i.e. southerners] and their children" and selling copper. That Ilu-shuma was able to sell copper to kings in the south is significant because it illustrates that Assur at this time was producing enough copper to sustain both itself and others. Where this copper came from is not clear, perhaps Assyrian miners made the long trip to Ergani in the north-west, in later texts described as a significant site of copper-mining.[26] According to his inscriptions, Ilu-shuma also constructed wells in Assur, used both as a source of water and to make bricks for the city wall.[23] Ilu-shuma was succeeded by his even more successful son, Erishum I (c. 1974–1934 BC),[27] the earliest king whose length of reign is recorded in the Assyrian King List, a later document recording the kings of Assyria and their reigns.[28] Erishum initiated the earliest known experiment in free trade, leaving the initiative for trade and large-scale foreign transactions entirely to his populace. Though large institutions, such as the temples and the king himself, did take part in trade, the financing itself was provided by private bankers, who in turn bore nearly all the risk (but also earned nearly all the profits) of the trading ventures.[29] Through Erishum's efforts, Assur appears to have quickly established itself as a prominent trading city in northern Mesopotamia.[30] Erishum earned some money himself through imposing tolls, which was put into expanding Assur itself: the temple of Ashur was rebuilt and expanded and a new temple, dedicated to the god Adad, was also constructed.[29]

Erishum's son and successor Ikunum (c. 1934–1921 BC)[31] rebuilt the fortification wall around Assur, an event which required financial contributions of silver not only from Assur itself but also from its widespread trading colonies. Whether the wall had to be rebuilt due to normal wear or due to having been damaged in war is not known. It is possible that it was damaged during conflict with the southern city-state Eshnunna, which at this time was pursuing an expansionist policy. In any case, repairs were not complete until the long reign of Ikunum's son Sargon I[32] (c. 1920–1881 BC).[31] Though Sargon's reign appears to have been a prosperous one during which Assyrian trade reached its peak,[32][33] the reigns of his son Puzur-Ashur II (c. 1880–1873 BC) and grandson Naram-Sin (c. 1872–1829/1819 BC)[31] saw Assur being threatened by foreign enemies, first by Ipiq-Adad II of Eshnunna and then by the more successful and dangerous Shamshi-Adad I of Ekallatum,[34] a city located near Assur.[35]

Trading colonies

Though evidence from Assur is scant, there are surviving rich textual records of Assyrian society and activity from the early Old Assyrian period, though they are not from Assur or northern Mesopotamia, but rather from central Anatolia. The largest known collection of old Assyrian tablets are from Kültepe, near the modern city of Kayseri. Kültepe, in this time period known by the name Kanesh, was also a city-state ruled by its own line of kings.[22] In the lower city of Kültepe, to the northwest, the Assyrians established a trade colony, or karum, out of which two levels (Ib, c. 1833–1719 BC, and II, c. 1950–1836 BC) have been archaeologically investigated.[36] Level II is particularly significant since it preserves about 22,000 cuneiform clay tablets that attest to a long-distance and extensive Assyrian trade network. The trade colony at Kültepe was a pivotal node in this network, which was centered in Assur and had extensive lesser trade posts throughout central Anatolia and likely Mesopotamia as well.[36] This trade network is the first noticeable impression left by the Assyrians in the historical record.[37] Assur was able to maintain its central position in the trade network despite being relatively small and having no history of military success.[1]

After the discovery of the Kültepe tablets in the 20th century, many historians suggested that they were evidence of a large "Old Assyrian Empire", stretching into Anatolia, but this interpretation is today discredited based on surviving archaeological and literary evidence. It is however possible that the cultural traditions that reached Assur during the time of its early trade network played some role in the rise of the first Assyrian territorial state centuries later.[8] Though an extensive number of Assyrian traders are known to have lived in the Kültepe trade colony, approximately 500 to 800 people, there are no obvious Assyrian elements in the settlement itself, apart from the tablets and seals. The houses in the colony can not be differentiated from the houses of the locals, which suggests that the traders lived not as colonists, but as expatriates, using the local artefacts and houses.[36] In all likelihood, the Assyrian community at Kültepe did not live in a separate walled part of the town, but rather simply in their own part of the lower city, also home to local Anatolians. The Assyrian colony was not only a trading settlement, but also functioned as a center of various craft production activities, such as the production of pottery and metal objects. The preserved cuneiform tablets demonstrate that the Assyrians had their own separate administrative structures and court at Kültepe, and thus were somewhat self-governing.[38] The Assyrian court at Kültepe based its rulings on Assyrian law, and often based its decisions on commands from Assur, sometimes issued by the kings themselves. In addition to trade, the cuneiform records at Kültepe also provide insight into the family lives of the traders, who often corresponded with their wives back home in Assur. These wives were in many cases responsible for gathering or acquiring the materials sold in the trading colonies.[39]

The original trading colony at Kültepe appears to have been burnt down c. 1836 BC, which led to the preservation of the thousands of tablets, but it was shortly thereafter rebuilt, as attested by the presence of later Assyrian activity in the second layer. In total, it has been estimated that during just the time of documented trade in Level II of the Kültepe trading colony, about twenty-five tons of Anatolian silver was transported to Assur, and that approximately one hundred tons of tin and 100,000 textiles were transported to Anatolia in return.[36] The Assyrians also sold livestock, processed goods and reed products.[40] In many cases, the materials sold by Assyrian colonists came from far-away places; the textiles sold by Assyrians in Anatolia were imported from southern Mesopotamia and the tin came from the east in the Zagros Mountains.[39] An Assyrian trader could probably make the 1,000 kilometer (620 mile) distance between Assur and Kültepe in six weeks, travelling through donkey caravans.[36][41] Though the traders had to pay road taxes and tolls to the various states and rulers in the lands in-between, profits were massive since the Assyrians sold many of their goods at double the price in Mesopotamia, or even more.[36] Assur's importance as a trading center declined in the 19th century BC, whereafter Assyrian traders played a more modest role. This decline might chiefly have resulted from increasing conflict between the states and rulers of the Ancient Near East leading to a decrease in trade in general.[1]

Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia

Conquests of Shamshi-Adad

From the 19th century BC until the end of the Old Assyrian period, the Assur city-state frequently came under the control of larger foreign states and empires.[42] The portion of the Old Assyrian period that is best historically attested, chiefly through extensive records found in the ruins of the city of Mari, is the time of Shamshi-Adad I (c. 1808–1776 BC) and his sons Ishme-Dagan I and Yasmah-Adad.[43] Shamshi-Adad (Samsi-Addu in his own Amorite language)[6] was an Amorite king, originally ruling the city of Ekallatum, where he had succeeded his father Ila‐kabkabuhu c. 1835 BC. Threatened by Ipiq-Adad II in Eshnunna, Shamshi-Adad sought refuge in southern Mesopotamia for several years but returned to Ekallatum c. 1811 BC and conquered his rival.[43] Three years later, in c. 1808 BC,[43] Shamshi-Adad deposed the last king of Puzur-Ashur I's dynasty,[35] Naram-Sin's son Erishum II (c. 1828/1818–1809 BC),[31] and took Assur for himself.[1]

After conquering both Eshnunna and Assur, Shamshi-Adad began extensive campaigns of conquest which culminated in his victory over Yahdun-Lim, the king of Mari, c. 1792 BC. Shamshi-Adad also went on to conquer cities to the north and east of Assur, such as Arrapha, Nineveh, Qabra and Erbil .[43] The realm founded by Shamshi-Adad eventually came to include most of northern Mesopotamia[1] and has been given various names by modern historians, such as the Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia[44] and the North-Mesopotamian Empire.[45] To rule this new realm, Shamshi-Adad established his capital at the city of Shubat-Enlil and in c. 1785 BC[43] placed his two sons in control of different parts of the kingdom as his vassals; Yasmah-Adad was granted Mari and the surrounding lands and Ishme-Dagan, the elder son, was granted Ekallatum, Assur and surrounding territories.[1] Under Shamshi-Adad's kingdom, Assur remained a distinct city and might have continued its trading with other cities. Local trade was evidently important for Shamshi-Adad, as there are from his reign records of an official overseeing merchants. Shamshi-Adad renovated the city and rebuilt the temples of Assur, though a sanctuary to the god Enlil also appears to have been added there, and Adad. Referring to the city as a city "full of gods", Shamshi-Adad respected Assur and sometimes stayed there to partake in religious ceremonies,[46] though he remained a foreign conqueror in the eyes of the locals and he placed his capital elsewhere.[47] The reason for making Shubat-Enlil his capital rather than Assur might have been that Assur was seen as formally ruled by the god Ashur, and had a powerful local city assembly, and was thus unattractive as a seat of power.[46]

Collapse of the kingdom

In the 18th century BC, Shamshi-Adad's kingdom became surrounded by competing large kingdoms. In the south, the rulers of Larsa, Babylon and Eshnunna fought with one another to re-unite southern Mesopotamia. In the east, the rulers of Elam increasingly involved themselves in Mesopotamian politics and in the west, new kingdoms arose at Yamhad and Qatna. The success and survival of Shamshi-Adad's kingdom relied chiefly on his own military success, strength and charisma. Increasing conflict with the surrounding kingdoms and Shamshi-Adad's death c. 1776 BC led to the collapse of the kingdom.[48] Local rulers quickly returned to power in many parts of the former realm, including in Mari,[49] where Zimri-Lim ousted Yasmah-Adad from power.[46] Shamshi-Adad's senior heir, Ishme-Dagan, retained control only of Ekallatum,[49] from where he ruled,[2] and Assur.[49] Ishme-Dagan was respectful of Assur's cults and traditions and occasionally used the city as his residence. His wife, Lamassi-Ashur was even named after the god Ashur.[46]

In c. 1772 BC, the new king of Eshnunna, Ibal-pi-el II invaded Ishme-Dagan's kingdom, occupying Assur, Ekallatum and Qattare before seizing Shamshi-Adad's old capital at Shubut-Enlil. Ishme-Dagan fled from his realm during this time, taking refuge in southern Mesopotamia, now ruled by the Old Babylonian Empire.[46] Ibal-pi-el II's invasion was eventually pushed back by Zimri-Lim of Mari and around this time, probably with the aid of the Babylonians, Ishme-Dagan returned to power in Ekallatum and Assur. A few years later, northern mesopotamia was again invaded, this time by an army from Elam that also seized Shubut-Enlil and other cities. This invasion was pushed back by an alliance between Mari, Ishme-Dagan and Babylon and in its aftermath, Ishme-Dagan strengthened his position by seizing some territory to the south and making a treaty with Eshnunna. When relations quickly thereafter soured again, Ishme-Dagan fled to Babylon once more. Assur and the rest of Ishme-Dagan's realm shortly thereafter came under the, perhaps only brief, control of the Old Babylonian Empire under Hammurabi (c. 1792–1750 BC),[50][51] who conquered the region c. 1761 BC[51] and appears to have respected Assur and its institutions since he wrote in one of his inscriptions that "I guided the people properly and returned to Assur its benevolent protective spirit".[50]

Assyrian Dark Age

The time between the collapse of Shamshi-Adad's kingdom in the 18th century BC and the rise of Assyria in the 14th century BC is often regarded by modern scholars as an Assyrian "Dark Age" due to the lack of sufficient historical evidence to clearly establish events during this time.[49] The main sources of historical records known from earlier Old Assyrian times; documents kept at other sites in northern Mesopotamia and in central Anatolia, fall silent in the 18th century BC and royal inscriptions and archival texts from Assur are very scanty in this time.[52] In any case it is apparent that Assur at some point returned to being an independent city-state.[49]

The Assyrian King List, the only real overarching source for the period,[53] presents a continuous sequence of rulers during this time,[49] but its account of at least the decades following Shamshi-Adad's death is clearly incomplete and does not fully reflect the politically uncertain time that followed,[54][55] when Shamshi-Adad's Amorite descendants, native Assyrians, and Hurrians appear to have fought one another for control of Assur.[56] According to the standard version of the list, Ishme-Dagan ruled for 40 years and was succeeded at Assur by the native Assyrian usurper Ashur-dugul.[31] Records at Mari establish that Ishme-Dagan only ruled for 11 years after his father's death, dying c. 1765 BC.[54] The king list also does not mention the brief conquests of Assur by outside powers, such as Eshnunna, Elam and Babylon during Ishme-Dagan's time.[3] Documents at Mari and a fragmentary alternate version of the king list also show that Ishme-Dagan was succeeded by his son Mut-Ashkur, who in turn was succeeded by Rimush. It is possible that these kings only ruled Ekallatum, and not Assur, but the Assyrian ruler Puzur-Sin, also absent in the king list, claims in one of his inscriptions to have deposed a-sí-nim, grandson (or descendant) of Shamshi-Adad and liberated Assur from the Amorites.[54][57] A-sí-nim is typically interpreted as a proper name, Asinum, in which case he was the last of Shamshi-Adad's dynasty to rule Assur, but it might alternatively have been a title, in which case the man driven away by Puzur-Sin could have been a local governor under Rimush.[54] In his inscription, Puzur-Sin prides himself on removing the ruler of "foreign seed" and demolishing their palace, erecting a religious sanctuary in its place. For these construction projects to have taken place, Puzur-Sin must have been able to maintain control over Assur for at least a few years.[58] Perhaps Puzur-Sin was omitted from the king list by mistake, or perhaps his omission reflects changing attitudes towards Shamshi-Adad and his dynasty by later Assyrians.[56]

Ashur-dugul, who ruled at some point after Puzur-Sin, is accorded a reign of six years by the Assyrian King List, which also states that his rule was challenged by six usurpers: Ashur-apla-idi, Nasir-Sin, Sin-namir, Ipqi-Ishtar, Adad-salulu and Adasi.[28] It is unclear if these figures were actually historical and actually claimed to be kings in opposition to Ashur-dugul. Their names are suspiciously similar to the eponyms (i.e. limmu officials) of Ashur-dugul's reign and they might thus in reality have been his generals and officials, misattributed as rival kings by the scribe who created the king list.[59] Ashur-dugul was according to the king list succeeded by Bel-bani,[31] c. 1700 BC,[60] apparently the son of Adasi.[31] Bel-bani founded the Adaside dynasty, which went on to rule Assyria for about a thousand years.[61] Later Assyrian monarchs, Bel-bani's descendants, would in times thereafter revere Bel-bani as a restorer of stability and as the founder of their long-lived dynasty. In time, he became an almost mythical ancestor figure.[62] It is possible that the Adaside dynasty originated as outsiders and that the family did not originally hail from Assur.[63] The name of Bel-bani's grandson[31] Shu-Ninua (c. 1615–1602 BC)[64] might mean "man from Nineveh"[e] and the repetition of the names Shamshi-Adad and Ishme-Dagan among the kings of the dynasty could suggest at least partial descent from Shamshi-Adad's dynasty.[63] The repetition of the names could alternatively be explained by Shamshi-Adad being revered by later generations as a great empire-builder.[66] The early kings of the Adaside dynasty also several times assumed names from the rulers of the Puzur-Ashur dynasty, including Erishum and Puzur-Ashur itself.[65]

Though it is not seen as reliable for the decades immediately following Shamshi-Adad's death, the Assyrian King List's account of the sequence of Assyrian kings and their reigns from Bel-bani onwards, when the rulers were securely based in Assur under a stable dynastic line, is thought to be reliable due to presumably being based on preserved chronological records. The precise relationships between the rulers might however not be fully reliable, as there is evidence to suggest that the genealogy of the early Adaside dynasty was at least partially reconstructed by later scribes.[67]

Rise of Assyria

In large parts, the invasion or raid of Mesopotamia by the Hittite king Mursili I in c. 1595 BC was critical to Assyria's later development. This invasion destroyed the then dominant power in Mesopotamia, the Old Babylonian Empire, which created a vacuum of power that led to the formation of the Kassite kingdom of Babylonia in the south[68] and the Hurrian[56] Mitanni state in the north.[68] The Hittite invasion must also directly have impacted Assur in some way, but there are no surviving sources discussing the matter.[49] Mitanni would in time become the dominant power in northern Mesopotamia, but in the power vacuum left after Mursili I's invasion, Assur also briefly rose to a first period of prominence.[4]

Assyrian rulers from c. 1520 to c. 1430 were more politically assertive than their predecessors, both regionally and internationally. Puzur-Ashur III (c. 1521–1498 BC) is the earliest Assyrian king to appear in the Synchronistic History, a later text concerning border disputes between Assyria and Babylonia, suggesting that Assyria first entered into diplomacy and conflict with Babylonia at this time[4] and that Assur at this time ruled a small stretch of territory beyond the city itself.[65] In the first half of the 15th century BC, there is also evidence of gifts for the first time being exchanged between Assyrian kings and Egyptian pharaohs.[4] It is clear the Assur experienced a period of prosperity from the late 16th to the early 15th century, as can be gathered from the royal inscriptions of Puzur-Ashur III, his two immediate predecessors Shamshi-Adad III (c.1563–1548 BC) and Ashur-nirari I (c.1547–1522 BC), and his successor Enlil-nasir I (c.1497–1485 BC), the first rulers with known royal inscriptions since Puzur-Sin's time. The inscriptions by these kings demonstrate that many of the buildings constructed earlier in the Old Assyrian period were repaired, rebuilt and extended under their reigns, including the temples dedicated to Ishtar and Adad, as well as the walls of the city itself. Under Puzur-Ashur III, the city walls were extended to cover a greater tract of land, presumably attesting to a growing population. Later documents also reference the construction of a "new city" (alu eššu) during this time, adding to the earlier "inner city" (libbi alī).[65]

Around c. 1430 BC, Assur was subjugated by Mitanni and forced to become a vassal, an arrangement that lasted for about 70 years, until c. 1360 BC.[4] Assur retained some autonomy under the Mitanni kings, as Assyrian kings during this time are attested as commissioning building projects, trading with Egypt and signing boundary agreements with the Kassites in Babylon.[69] Chiefly responsible for bringing an end to Mitanni rule was another Hittite king, Šuppiluliuma I, whose 14th century BC war with Mitanni over control of Syria effectively led to the beginning of the end of the Mitanni kingdom.[70][71] At the same time as the Mitanni king Tushratta had to fight Šuppiluliuma I, he was also forced to contend with a rival claimant to the throne, Artatama II. After the war with the Hittites relegated Mitanni to a minor kingdom, Assyria managed to free itself from its suzerain. Assyria's independence, achieved under the king Ashur-uballit I (c. 1363–1328 BC) and Ashur-uballit I's conquests of nearby territories, most importantly the fertile region between the Tigris, the foothills of the Taurus Mountains and the Upper Zab, marks the transition between the Old and Middle Assyrian periods,[72] though Assur's transformation into a territorial state appears to have already begun under the last few decades of Mitanni rule.[73] Ashur-uballit I was the first native Assyrian ruler to claim the dignity of king (rather than governor).[42] Shortly after achieving independence, he further claimed the dignity of a great king on the level of the pharaohs and the Hittite kings.[72]

Archaeological evidence

Little archaeological finds have been discovered dating to the Old Assyrian period other than the trade archives at Kültepe. The lack of substantial finds at Assur is probably attributable to later Assyrian kings expanding and rebuilding portions of the city, which left few traces of the original Old Assyrian structures.[74] Surviving finds at Assur include a new phase of the city's Ishtar temple (dubbed Ishtar D), built during the preceding Early Assyrian period, as well as an early palace.[75] The new Ishtar temple measured 34 by 9.5 meters (111.5 by 31.2 feet) and was substantially larger than preceding temples at the site. This temple included a large rectangular cult room which worshipper entered from the side.[75]

The Old Assyrian palace at Assur, dubbed the Urplan Palace by archaeologists, was an enormous structure, measuring 98 by 112 meters (321.5 by 367.5 meters), and included a large central court surrounded by several smaller courts, though it appears to never have been completed.[75] The construction does not seem to have progressed beyond cutting foundation trenches, though some scant evidence suggests that some of these foundation trenches were later reused for a poorly known construction project during the reign of Shamshi-Adad I.[76]

Little evidence survives on non-monumental buildings in Assur.[45] Not a single house has been excavated, nor have any private archives of its citizens been discovered.[74] Over seventy graves are however known from the site, dated to between 2500 and 1500 BC. The graves differ in design and in how many bodies were buried, and include bodies placed in pits, large ceramic vessels and tombs with vaulted roofs built with stone or mudbrick. The vaulted tombs are of particular significance as the same type of tombs were later used by prominent Assyrian families to bury their dead collectively beneath their houses, illustrating that this was a long-lasting Assyrian tradition. Several of the tombs contain rich funeral gifts, including jewelry, seals, stone objects and weapons.[45]

Government

Kingship and administration

| Old Assyrian kings |

|---|

|

[77][78][79] Puzur-Ashur dynasty |

|

| Shamshi-Adad dynasty |

|

| Non-dynastic |

|

| Adaside dynasty |

|

Assur in the Old Assyrian period was in many respects an oligarchy, where the king was a permanent, albeit not the only prominent, official in the city's politics.[45] Unlike in later Assyrian periods, the Assyrian kings of the Old Assyrian period are not thought to have been autocrats (i.e. rulers with sole power),[f] but rather they acted as the stewards of the city's god, Ashur, and presided over the meetings of the Ālum (city assembly),[24][76] Assur's main administrative body in this time.[80] The kings in the Old Assyrian period appears to have mainly functioned as the assembly's executive officers and chairmen. In documents from Kültepe, it is common to find mentions of "the City" (i.e. the city assembly) passing verdicts in judicial matters. Documents also however attest to rulers often being approached for legal advice, as they were seen as "constitutional experts".[80] Though the Assyrian kings themselves used the style Išši'ak, the citizens of Assur often referred to them with the style rubā’um ("great one"), clearly indicating authority and the status of being a primus inter pares (first among equals). Since the same title was used to refer to the kings in Anatolia, whom the Assyrians traded with, it also shows understanding of their king as a royal (and not simply civic or religious) figure.[81]

The composition of the city assembly is not known, but it is generally believed to have been made up of members of the most powerful families of the city,[45] many of whom were merchants.[30] From the time of Erishum I onwards,[74] a yearly office-holder, a limmu official, was elected from this body of citizens. The limmu official held substantial executive powers and gave their name to the year, which meant that their name appeared in all administrative documents of that year. Kings were usually the limmu officials in their first regnal years.[45] The city assembly is described to have convened either in a "sacred precinct" (ḫamrum) in the "Step Gate" (mušlālum) behind the temple of Ashur. In this sacred place, where oaths were also sworn, there were seven statues of divine judges. At other times, the assembly may have convened in a structure referred to in texts as the "city hall" (bēt ālim).[82] The city hall was run by the limmu official and was an important institution that managed the city's finances through collecting taxes and fines and also acted as a public warehouse, selling certain wares, such as barley and precious metals. On some wares, such as lapis lazuli and iron, the city all appears to have had a local monopoly.[83] Documents from Kültepe have shown that the verdicts of the local court, and thus possibly also the city assembly in Assur as well, during this time were reached by majority vote: the assembly was first divided into three groups and if no unamity was reached divided further into seven groups. A smaller group within the assembly, referred to as "the Elders" in a handful of texts, may have been the ones to finally pass verdicts.[82]

Assur first experienced a more autocratic form of kingship under Shamshi-Adad I,[45] the earliest ruler of Assur during the Old Assyrian period to assume the style šarrum (king)[84] and the title 'king of the Universe'.[85] Shamshi-Adad appears to have based his more absolute form of kingship on the rulers of the Old Babylonian Empire.[86] In one of his royal inscriptions at Assur, Shamshi-Adad assumed the full style "king of the Universe, builder of Assur's temple, pacifier of the land between Tigris and Euphrates". In some inscriptions and seals this style was preceded by "appointee of Enlil" and/or succeeded by "beloved of Ashur". On inscribed bricks, used in the construction projects, Shamshi-Adad was more modest and assumed the for Assur more traditional style of ensí (the Sumerian version of the Assyrian Išši'ak) of Ashur.[87] Under Shamshi-Adad, Assyrians also swore their oaths by the king, not just by the god. This practice did not survive beyond his death.[88]

Royal seals

In Ancient Mesopotamia, royal seals served as both instruments of office and personal seals for the kings.[89] Only four royal seals from the kings of the Puzur-Ashur dynasty are known, though only from their impressions, coming from Erishum I (two seals), Sargon I and Naram-Sin. With the sole exception of one of the seals of Erishum, found on a ceramic jar from Assur, they are all from the cuneiform tablets found at Kültepe.[90] The known seals of the Puzur-Ashur dynasty kings are highly consistent in content, both in the text and in the artwork. The inscriptions of the seals all include the name of the king, the title Išši'ak Aššur and further text establishing him as the son of the preceding king.[89] When compared to other seals of non-royal Assyrians in the Old Assyrian period, the motif itself—a goddess who is holding the hand of a bald man and leading him to a seated ruler with brimmed, rounded headgear—is not very distinctive and appears in other seals as well. An aspect that is distinctive when compared to the other seals is that there are no "filler figures" between the four primary figures depicted, making the space between them appear larger and the figures themselves stand out more.[91]

In terms of the artwork and the layout, the Puzur-Ashur dynasty seals are reminiscent of the seals of the kings of the Third Dynasty of Ur,[89] though noticeable differences do exist, such as the presence of a second goddess behind the seated ruler, a very rare motif in both Ur III seals and in seals of non-royal Assyrians of the Old Assyrian period.[92] In Ur III seals, the seated ruler was the divinely ordained king of Ur, but as the rulers of Assur were not regarded as divine themselves, but rather as servants of Assur's true king, the god Ashur, this connotation would have been ideologically problematic. It is possible that the seated figure in the Puzur-Ashur dynasty seals should be interpreted as Ashur, with the bald servant being led before him by a goddess being the Assyrian king.[93] Though the seated figure is not given any other visual markers of divinity (such as horns or other non-human body features), the symbolism alone could not theologically be applied by the Old Assyrians to anyone but Ashur.[94]

Shamshi-Adad I retained in his more absolute kingship certain aspects of the royal ideology of the Puzur-Ashur dynasty as well and a mix of the traditions can be seen in his royal seals from Assur. The inscription designated him as "Shamshi-Adad, beloved of Ashur, Išši'ak Aššur, son of Ila-kabkabu", similar to the inscriptions of the Puzur-Ashur dynasty kings, but the visual depiction of Shamshi-Adad himself was noticeably different. Depicted with brimmed headgear, a full beard and one raised hand and one hand close to his body, Shamshi-Adad is in his seal more similar to the rulers of the Old Babylonian Empire than the preceding rulers of Assur. The middle portion of his seal is not known due to the fragmentary nature of all known surviving impressions, which means that it is impossible to determine whether a seated figure was depicted there or not.[86]

Society

Population and culture

The distinct burial practices in Old Assyrian Assur suggests that a distinct Assyrian identity formed already in this period. Cultural practices such as burials, dress codes and foods are typically critical to the formation and maintenance of ethnic and cultural identities. Perhaps the distinct identity of the early city-state was reinforced by its frequent contact with foreigners through its trade network.[8] A verdict issued under one of the kings of the Puzur-Ashur dynasty decided that "Assyrians can sell gold among each other but, in accordance with the words of the stele, no Assyrian whosoever shall give gold to an Akkadian,[g] Amorite or Subaraean",[h] illustrating that the Assyrians viewed themselves as a distinct group.[95] Though Old Assyrian evidence concerning personal lives from Assur itself is limited, consisting of a few marriage contracts and wills, the extensive Old Assyrian cuneiform records found at Kültepe document not only the participation of the traders in the Assyrian trade network, but also their everyday life not only in Kültepe but also at home in Assur.[96]

There was no legal distinction between men and women during the Old Assyrian period and they had more or less the same legal rights.[95] Both men and women had to pay the same fines, could inherit property, participated in trade, bought, owned and sold houses and slaves, made their own last wills and were allowed to divorce their partners.[97] Society was instead divided into two main groups: slaves (subrum) and free citizens, referred to as awīlum ("men") or DUMU Aššur ("sons of Ashur"). Among the free citizens there was also a division into rabi ("big") and ṣaher ("small") members of the city assembly.[98]

Old Assyrian families

Marriages in Old Assyrian Assur were decided and arranged between the prospective groom or his family and the parents of the prospective bride; usually marriages took place at the time the bride-to-be reached adulthood.[97] Marriage gifts were customary; some texts mention that betrothals were broken off when no gifts were given. The dowry given to the bride belonged to her, not the husband, and was inherited by her children after her death. After the marriage was complete, wives moved in with their husbands, who were obliged to provide them with garments and food. Marriages were typically monogamous, but husbands were allowed to buy a female slave (sometimes chosen by the wife) in order to produce heirs in case his wife had not given birth to a child after being married for two or three years. This woman remained a slave, however, and was never seen as a second wife.[99] Old Assyrian families sometimes hired wet nurses (mušēniqtum), who were paid for their work. If a mother died, young children were entrusted to the care of other family members, such as her or her husband's grandparents or aunts and uncles.[100] Male and female children were raised differently. Girls typically lived with their mother, being taught to spin and weave and helping with daily tasks, whereas boys were taught by masters to read and write and then often followed their fathers to Anatolia to learn how to trade. The eldest daughter was sometimes consecrated to a god (presumably Ashur) as priestesses. Consecrated women were not allowed to marry but also became economically independent.[101]

During the long trading journeys, the wives of Assyrian traders often stayed home alone in Assur, managing households and raising children.[95] Often they had to, as the heads of the household, oversee gathering food and supplies, repairing the house and providing clothing for the children. Sometimes they had to live with their in-laws, not always successfully.[100] Because the Assyrian traders in Anatolia could be away for long periods of time, they were allowed to take second wives in Anatolia. This arrangement had certain rules, including that the two wives could not be of the same status (one had to be the aššatum, "main wife", and the other the amtum, "second wife"), they could not both live in the same region (one had to live in Assur and the other in Anatolia) and a third wife in one of the trading posts in-between Assur and Anatolia was not allowed. Both wives also had to be provided with food, wood and a house to live in.[99] Children born of the "second wife" may have had less rights in regards to inheritance than those of the "main wife".[102]

Most divorces recorded in the surviving texts were consensual and resulted from private discussions and arrangements. The high fines for divorce, up to 5 minas of silver, had to be paid by both the husband and wife and both were allowed to remarry afterwards. If a man grew to dislike his wife, he could return her to her family, but had to pay compensation. If the wife had behaved badly in some way, the husband could strip her of her possessions and chase her away. Divorces with the second wife in Anatolia were more common than divorces in Assur itself, resulting from their husbands retiring from trading and staying in Assur permanently. In these cases, the husband had to decide whether to take his children with him or not, and had to pay certain amounts of money depending on how many of the children he took. If a husband died, his children inherited his goods and had to take care of their mother. If there were no children, the wife kept her dowry for herself and was allowed to remarry. If the husband had written a will, his wife could also inherit his goods and estates.[103] If a man had died with unpaid debts, his sons became responsible for paying them before receiving their inheritance. Daughters held no responsibility for unpaid debts. Both sons and daughters, though primarily the sons, were responsible for caring for their elderly parents and after they died, were also responsible for organizing and paying for their funerals. After the funeral ceremony, there was an extended period of mourning. It was believed that the deceased lived on in the Ancient Mesopotamian underworld as ghosts and that they could appear in the dreams of their descendants. Deceased family members were often honored with prayers and offerings, a practice made easier since they were typically buried beneath the houses of their descendants and relatives.[104]

Slavery

Slavery was an important part of nearly every society in the Ancient Near East. In the Akkadian language, several terms were used for slaves, commonly wardum, though this term could confusingly also be used for (free) official servants, retainers and followers, soldiers and subjects of the king. Because many individuals designated as wardum in Old Assyrian texts are described as handling property and carrying out administrative tasks on behalf of their masters, many may have in actuality been free servants and not slaves in the common meaning of the term.[11] A number of wardum are however also recorded as being bought and sold.[105] All other terms used for slaves also had secondary or alternative meanings in other contexts:[105] for instance, the term subrum (used to refer to a collection of slaves)[106] could also mean utensils or livestock[105] and the term amtum (used for female slaves)[106] was the same word as the word used for second wives.[105] Another term that was sometimes used as a synonym for wardum was ṣuḫārum (female version ṣuḫārtum),[107] though this word could also be used to refer to a child.[105]

Though Old Babylonian texts frequently mention the geographical and ethnic origin of slaves, there is only a single known such reference in Old Assyrian texts, a slave girl explicitly being referred to as Subaraean, indicating that these aspects were not seen as very important.[107] There were two main types of slaves: chattel slaves, primarily foreigners who were kidnapped or who were spoils of war, and debt slaves, formerly free men and women who had been unable to pay off their debts. Many chattel slaves were Anatolians who had originated as debt slaves but had lost their right to redemption.[108] In some cases, Assyrian children were seized by authorities due to the debts of their parents and sold off into slavery when their parents were unable to pay.[97] Children born to slave women automatically became slaves themselves,[109] unless some other arrangement had been agreed to.[106]

Owning several slaves was considered a sign of wealth, similar to owning several houses; on average a male slave cost 30 shekels and a female slave 20 shekels. Typically slaves from Anatolia, where Assur had prominent trading colonies, were less expensive than slaves from Mesopotamia. Slaves were owned by both women and men, with many women being recorded as both purchasing and inheriting slaves of their own. Female slaves were tasked with cleaning, preparing meals and helping their owners in raising their children. At times, men engaged in sexual relations with their female slaves and they were sometimes forced to become pregnant and give birth to children on behalf of infertile owners. Some male slaves worked in the international trade as personnel in the trading caravans.[106] The major institutions in Assur, such as the city hall and temple of Ashur, owned slaves which were used for various maintenance duties. Slaves were sometimes sold to pay off debts,[106] and were sometimes taken by force by authorities as security for debts.[97]

Economy and trade

A major portion of the Old Assyrian population appears to have been involved in the international trade[96] and it was largely organized around family businesses: every family member had specific tasks to perform and many professional relationships were founded in family ties. This is also reflected by the vocabulary used when referring to businesses; the boss, who often stayed at home in Assur and did not travel to the trading colonies, was typically referred to as abum ("father"), partners were called aḫum ("brothers") and employees were called ṣūḫārū (younger family members). Enterprises were often called bētum ("house").[110] As can be gathered from hiring contracts and other records, the trade involved people of many different occupations, including porters, guides, donkey drivers, agents, traders, bakers and bankers.[106] In family-run businesses, the eldest son was typically the one to move to Kültepe and other trading colonies whereas the father stayed at home. The other sons, if there were any, could also be settled in the colonies and often helped with transporting the goods themselves. Women were also part of the businesses, particularly through weaving the textiles that their male relatives then sold.[111] The women themselves received the gold or silver payment for these textiles and could in many transactions represent their husbands and brothers.[112] Sons could after their father's deaths either inherit their father's business or choose to start their own enterprises.[111]

Some of the most common cuneiform tablets recovered from Kültepe are loan contracts, both within the Assyrian community or between the Assyrian traders and the locals. Non-commercial loans often consisted of small quantities of silver and were given out with interest; this interest amounted to 30% every year for Assyrians, though it was higher for the locals in the trading colonies. Loans usually had to be paid back within a short timespan, typically within a year, and successful repayment was marked by the loan contractor returning the cuneiform tablet recording the loan, sometimes alongside a receipt.[113]

Cuisine and diet

Evidence of what the citizens of Assur itself ate during the Old Assyrian period is very limited, consisting only of a few mentions in letters of wives buying barley and preparing bread and beer. By and large, food was prepared by the women. More detailed records of food are available from the cuneiform records at Kültepe, which establish that bread and beer were the main food and drink products (water as well, though this was taken for granted and is thus typically not mentioned in the texts). Two varieties of bread were eaten; sourdough bread and bread made only with water and flour. Animal fat and sesame oil were sometimes used in cooking. To enhance flavors, honey was sometimes added as a sweetener, and common herbs and spices included salt, cumin, coriander and mustard. Meat, often grilled or in stews, was also eaten, with records of Assyrians eating sheep, oxen, pork, shrimp and fish. Animals were often killed at home, but it was also possible to purchase pre-cut pieces of meat, either in Assur or by traders along the travel routes.[114]

Though beer and water were the primary drinks, the preserved texts also demonstrate a great appreciation for wine,[114] seen as a luxury commodity and called kerānum or, more rarely, karānum in Assyrian.[115] Wine was mainly made from grapes grown in Cappadocia,[114] though other sources existed as well, such as southern Anatolia or certain sites alongside the Euphrates river or Taurus Mountains.[116] When they drank beer, Assyrians typically also ate beer bread, made of crushed barley.[114] In certain situations, consumption of beer appears to have been formalized; the cuneiform texts found at Kültepe indicate that Old Assyrian traders bought and consumed beer when buying an animal, completing a journey, crossing a river, and when arranging meetings with important officials. It is also clear that guards and toll officials were paid not only in money, but were also regularly offered gifts such as beer. Wine appears to have been consumed in some ritualistic contexts, such as when swearing an oath to a deity.[117]

Language

The language used to inscribe the Assyrian tablets found in central Anatolia is generally referred to as Old Assyrian,[22][118] a Semitic language (i.e. related to modern Hebrew and Arabic) closely related to Babylonian, spoken in southern Mesopotamia.[42] Both Assyrian and Babylonian are generally regarded by modern scholars to be distinct dialects of the Akkadian language.[8][42][119][120] This is a modern convention as contemporary ancient authors considered Assyrian and Babylonian to be two separate languages;[120] only Babylonian was referred to as akkadûm, with Assyrian being referred to as aššurû or aššurāyu.[121] Though both were written with cuneiform script, the signs look quite different and can be distinguished relatively easily.[42]

Old Assyrian texts are for the most part limited to the early portion of the period, before the "Dark Age" from the 18th century BC onwards.[121] The signs used in the texts from these times are for the most part less complex than those used during the succeeding Middle and Neo-Assyrian periods and they were fewer in number, amounting to no more than 150–200 unique signs,[122] most of which were syllabic signs (representing syllables).[118] As letters sometimes include awkwardly shaped signs and spelling mistakes, it is likely that most preserved Old Assyrian texts were written by the authors themselves (and not hired scribes). Since some such letters are by women, it is evident that at least some women learned to read and write.[122] Due to the limited number of signs used, Old Assyrian is relatively easier to decipher for modern researchers than later forms of the language, though the limited number of signs also means that there are in cases several possible alternative phonetic values and readings.[118][123] This means that while it is easy to decipher the signs, many researchers remain uncomfortable with the language itself.[123] Though it was a more archaic variant of the later Assyrian language,[123] Old Assyrian also contains several words that are not attested in later periods, some being peculiar early forms of words and others being names for commercial terms or various textile and food products from Anatolia.[124]

Calendar

Like the calendars used by the early Egyptians and Arabs, the Old and Middle Assyrian calendar consisted of twelve months, each allotted three constellations (one constellation corresponding to a period of ten days). In Assyria, the months were named Ab sharrāni, Khubur, Ṣippum, Qarrātum, Tanmarta, Ti'inātum (or Sîn), Kuzallu, Allanātum, Bēlti-ekallim, Narmak Ashur sha sarrātim, Narmak Ashur sha kinātim and Makhur ilī. Several of the names demonstrate the astronomical origin of the calendar. For instance, Tanmarta was also used to refer to the heliacal rising of the star Sirius, Bēlti-ekallim was also the name of a goddess who was represented in the sky by the star Vega, and the name of the final month, Makhur ilī, means "meeting of the gods", probably in reference to conjunction of the moon and the Pleiades star cluster in the sky during this time.[125] The Assyrian calendar must have started in the autumn, at the time when the farmers ploughed the fields, sometime between September 23 (the September equinox) and December 21 (the winter solstice).[126]

The Old and Middle Assyrian calendar was not without its problems.[127] An extra week, a time-unit referred to as ḫamuštum, had to be added to the twelve thirty-day months. This appears to have normally been done in the form of adding an extra full month every four years.[126] Furthermore, eponym years did not always begin with the change of a year, but instead often coincided with stellar phenomena. If an eponym ended in the middle of a month, the next eponym also started with that month which means that sometimes the same month was repeated. As a result of its issues, the seasons over time moved backwards through the months of the Assyrian calendar by the speed of about one month every 120 years. In the 13th century BC, during the Middle Assyrian period, King Shalmaneser I had to adjust and correct the calendar, moving the months back to their original intended position.[127]

Religion

The Assyrians worshipped the same pantheon of gods as the Babylonians in southern Mesopotamia.[119] As known Old Assyrian texts are concerned mainly with trade, knowledge of Assyrian religion in the Old Assyrian period is not as detailed as in later periods.[128] The chief deity in Assur in the Old Assyrian period, and in later times as well, was the Assyrian national deity Ashur.[129][130] Though the deity and the city are commonly distinguished by modern historians through calling the god Ashur and the city Assur, both were inscribed in the exact same way in ancient times (Aššur). Because Old Assyrian documents sometimes appear to not differentiate between the city and the god, it is believed that Ashur is a deified personification of the city itself. Perhaps the site of the city, originating as a holy site prior to the city's construction and settled due to its strategic location came to gradually be regarded as divine in its own right at some point in the preceding Early Assyrian period.[13] Ashur's role as a deity was flexible and changed with the changing culture and politics of the Assyrians themselves. Though he would in later centuries be regarded as a god of war, guiding the Assyrian kings on their campaigns, he was in Old Assyrian times seen as a god of death and revival, related to agriculture.[131]

One of Ashur's main functions was also justice: it was believed that anyone who gave false testimony or unjust judgement in court would be struck down by "Ashur's dagger" (Patrum ša Aššur),[132][133] a weapon Assyrians had to take oaths on.[128][133] Women also took oaths on the "tambourine (huppum) of Ishtar".[128][133] Both of these objects were likely physical divine emblems in Assur.[133] The temples dedicated to Ashur in both Assur and the Assyrian trading colonies evidently included statues of the god and representations of his divine objects since one of the preserved texts describe thieves breaking into the Ashur temple in Kültepe and stealing Assur's dagger and a sun-disc that was placed on his chest.[133]

Ashur is frequently alluded to in surviving Old Assyrian texts and inscriptions. Assyrian texts from Kültepe show that Assyrians swore their oaths by "the City and the prince" or "the City and the lord", "prince" and "lord" probably meaning Ashur. In several texts, family members at home in Assur wrote to the traders in Kültepe that they ought to return to Assur and "come and see the eye of Ashur" or "seize Ashur's foot", suggesting that the god disapproved of his subjects leaving his city for too long periods of time only for the sake of monetary gain, even though there were sanctuaries dedicated to Ashur in all of the trading colonies as well.[134] Women were evidently greatly concerned with religion, recorded as making offerings, paying tribute to the gods and reminding their husbands of their duties to the gods.[128] In one text, two women wrote the following message to the prominent trader Imdu-ilum:[134]

Ashur warned you over and over again. You love money, (but) neglect your soul; can you not do Ashur's will in the City! Urgent! When you hear this message come and see Ashur's eye and save your soul![134]

In addition to Ashur, other prominent gods worshipped by the Assyrians of the Old period included the Sumerian weather-god Enlil, possibly because the weather-god had held a prominent role in the Hurrian pantheon. More prominent than Enlil was the Semitic weather-god Adad, whose name was also incorporated into about one tenth of the names of known individuals of the period. Equally prominent as Adad was the moon-god Sîn, whose name was also incorporated into about a tenth of all known Old Assyrian individuals, and who in later times became one of the major patron deities of the Assyrian royal family. Though names with Sîn are common, the presence of the name "Laban" in some Old Assyrian names indicates that Sîn was also sometimes worshipped under that name, otherwise used for him in the region corresponding to modern Lebanon.[136] Another prominent deity was the goddess Ishtar,[137] who had been worshipped at Assur since early in the preceding Early Assyrian period and was probably the original primary deity of the settlement.[138]

Few texts of purely religious nature (i.e. not just allusions in other texts) are known from the Old Assyrian period. Known Assyrian religious texts from this time include a poem describing an evil demon, the daughter of the sky-god Anu who was cast down to Earth by her father due to her evil schemes. This demon worked in mankind's favor, attacking those who behaved against the will of the gods and weakening dangerous animals, such as lions. Another text, specifically related to merchant activities, discusses a demon in the shape of a black dog who lies in wait for merchant caravans. This demon was possibly related in some form to the water-god Enki and might have embodied thirst.[130]

See also

Notes

- ^ The Old Assyrian period is generally regarded to end with the accession of Ashur-uballit I c. 1363 BC; the commonly used date is the end of the reign of his predecessor, Eriba-Adad I, c. 1364 BC (Assyrian regnal years were generally counted from the first full year as king).

- ^ Assur was not independent throughout the entire Old Assyrian period. In the 18th century BC, Assur was incorporated into the short-lived Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia under the Amorite king Shamshi-Adad I, ruled from Shubat-Enlil.[1] After Shamshi-Adad's death, Assur briefly remained under the control of his family, then ruling from Ekallatum.[2] At times, Assur also fell under the control of Mari, Elam and Babylon.[3] Later, c. 1430–1360 BC, Assur became a vassal state of the western Mitanni kingdom.[4]

- ^ Where applicable, this article follows the conventionally used middle chronology of Mesopotamian history

- ^ The Old Assyrian period is sometimes alternatively defined as covering a shorter timespan, from Puzur-Ashur I to the death of Ishme-Dagan I c. 1765 BC. After Ishme-Dagan's death, Assyria entered into a "Dark Age" lasting until the beginning of the Middle Assyrian period, with few known surviving sources.[5] In this division scheme, the period between the shortened Old Assyrian period and the Middle Assyrian period is sometimes referred to as the "Transition period".[6]

- ^ The name is alternatively read as "Kidin-Ninua", "under the protection of (the deity of) Nineveh", a name also with obscure political implications.[65]

- ^ In this respect, the Urplan Palace appears to be somewhat at odds with the role of the kings.[76] It is possible that the palace was constructed under the more autocratic Shamshi-Adad I, but that would place it at a later point in time than it is conventionally dated.[45]

- ^ Here referring to the people of southern Mesopotamia.[95]

- ^ The Hurrians who lived north of Assur.[95]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Garfinkle 2007, p. 67.

- ^ a b Reade 2001, p. 5.

- ^ a b Veenhof 2017, pp. 66, 68.

- ^ a b c d e Düring 2020, p. 42.

- ^ Veenhof 2003, p. 58.

- ^ a b Yamada 2017, p. 108.

- ^ a b Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Düring 2020, p. 39.

- ^ Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 21.

- ^ Nemirovsky, A (12 September 2020). Fast Way Upstairs: Transformation of Assyrian Hereditary Rulership in the Late Bronze Age. Springer International Publishing. p. 142. ISBN 9783030514372. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ a b de Ridder 2017, p. 49.

- ^ Michel 2017, pp. 81, 84.

- ^ a b Lambert 1983, pp. 82–85.

- ^ Frahm 2017b, p. 5.

- ^ Roux 1992, p. 187.

- ^ Aubet 2013, p. 276.

- ^ Veenhof 2003, p. 59.

- ^ Veenhof 2017, p. 57.

- ^ Veenhof 2017, p. 59.

- ^ a b c Lewy 1971, p. 754.

- ^ Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Düring 2020, p. 33.

- ^ a b Veenhof 2017, p. 60.

- ^ a b Radner 2015, p. 3.

- ^ Veenhof 2017, p. 62.

- ^ Lewy 1971, pp. 756–758.

- ^ Lewy 1971, p. 758.

- ^ a b Lendering 2006.

- ^ a b Lewy 1971, pp. 758–759.

- ^ a b Veenhof 2017, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chen 2020, p. 198.

- ^ a b Lewy 1971, p. 761.

- ^ Veenhof 2017, p. 63.

- ^ Lewy 1971, p. 762.

- ^ a b Lewy 1971, p. 740.

- ^ a b c d e f Düring 2020, p. 34.

- ^ Garfinkle 2007, p. 63.

- ^ Düring 2020, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Garfinkle 2007, p. 66.

- ^ Garfinkle 2007, p. 64.

- ^ Garfinkle 2007, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d e Radner 2015, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e Veenhof 2017, p. 65.

- ^ Van De Mieroop 2016, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Düring 2020, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e Veenhof 2017, p. 66.

- ^ Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 25.

- ^ Garfinkle 2007, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d e f g Garfinkle 2007, p. 69.

- ^ a b Veenhof 2017, p. 68.

- ^ a b Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 30.

- ^ Yamada 2017, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Yamada 2017, p. 109.

- ^ a b c d Reade 2001, p. 6.

- ^ Lewy 1971, p. 750.

- ^ a b c Yamada 2017, p. 112.

- ^ Chavalas 1994, p. 120.

- ^ Lewy 1971, p. 749.

- ^ Reade 2001, p. 7.

- ^ Bertman 2003, p. 81.

- ^ Frahm 2017, p. 191.

- ^ Brinkman 1998, p. 288.

- ^ a b Reade 2001, p. 8.

- ^ Bertman 2003, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d Yamada 2017, p. 113.

- ^ Lewy 1971, p. 748.

- ^ Yamada 2017, p. 110.

- ^ a b Düring 2020, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Yamada 2017, p. 114.

- ^ Düring 2020, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Garfinkle 2007, p. 70.

- ^ a b Düring 2020, p. 43.

- ^ Yamada 2017, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Veenhof 2017, p. 58.

- ^ a b c Düring 2020, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Düring 2020, p. 37.

- ^ Chen 2020, pp. 197–199.

- ^ Düring 2020, p. xvi.

- ^ Bertman 2003, pp. 81, 85, 89, 91, 92, 104.

- ^ a b Veenhof 2017, p. 70.

- ^ Veenhof 2017, p. 71.

- ^ a b Veenhof 2017, p. 72.

- ^ Veenhof 2017, p. 73.

- ^ Chavalas 1994, p. 117.

- ^ Bertman 2003, p. 103.

- ^ a b Eppihimer 2013, p. 49.

- ^ Veenhof 2017, pp. 66, 70.

- ^ Veenhof 2017, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Eppihimer 2013, p. 37.

- ^ Eppihimer 2013, p. 36.

- ^ Eppihimer 2013, p. 38.

- ^ Eppihimer 2013, p. 40.

- ^ Eppihimer 2013, p. 43.

- ^ Eppihimer 2013, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e Michel 2017, p. 81.

- ^ a b Michel 2017, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d Michel 2017, p. 84.

- ^ Michel 2017, pp. 81, 83.

- ^ a b Michel 2017, p. 85.

- ^ a b Michel 2017, p. 88.

- ^ Michel 2017, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Michel 2017, p. 86.

- ^ Michel 2017, p. 87.

- ^ Michel 2017, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e de Ridder 2017, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d e f Michel 2017, p. 83.

- ^ a b de Ridder 2017, p. 51.

- ^ de Ridder 2017, p. 56.

- ^ de Ridder 2017, p. 57.

- ^ Michel 2017, p. 91.

- ^ a b Michel 2017, p. 92.

- ^ Michel 2017, p. 94.

- ^ Michel 2017, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b c d Michel 2017, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Barjamovic & Fairbairn 2018, pp. 249, 251.

- ^ Barjamovic & Fairbairn 2018, p. 250.

- ^ Barjamovic & Fairbairn 2018, pp. 256–257.

- ^ a b c Luukko & Van Buylaere 2017, p. 315.

- ^ a b Garfinkle 2007, p. 54.

- ^ a b Luukko & Van Buylaere 2017, p. 313.

- ^ a b Luukko & Van Buylaere 2017, p. 314.

- ^ a b Michel 2017, p. 100.

- ^ a b c Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 111.

- ^ Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 112.

- ^ Lewy 1971, p. 769.

- ^ a b Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 238.

- ^ a b Lewy 1971, p. 770.

- ^ a b c d Michel 2017, p. 99.

- ^ Lambert 1983, p. 83.

- ^ a b Lewy 1971, p. 763.

- ^ Breasted 1926, p. 164.

- ^ Lewy 1971, p. 766.

- ^ a b c d e Veenhof & Eidem 2008, p. 103.

- ^ a b c Lewy 1971, p. 764.

- ^ "Cylinder seal British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ Lewy 1971, pp. 766–768.

- ^ Lewy 1971, p. 767.

- ^ Mallowan 1971, p. 300.

Bibliography

- Aubet, Maria Eugenia (2013). Commerce and Colonization in the Ancient Near East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51417-0.

- Barjamovic, Gojko; Fairbairn, Andrew (2018). "Anatolian Wine in the Middle Bronze Age". Die Welt des Orients. 48 (2): 249–284. doi:10.13109/wdor.2018.48.2.249. JSTOR 26606978. S2CID 167103254.

- Bertman, Stephen (2003). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518364-1.

- Breasted, James Henry (1926). The Conquest of Civilization. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers. OCLC 653024.

- Brinkman, J. A. (1998). K. Radner (ed.). The Prosopography of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Volume 1, Part II: B–G. The Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project.

- Chavalas, Mark (1994). "Genealogical History as "Charter": A Study of Old Babylonian Period Historiography and the Old Testament". In Millard, A. R.; Hoffmeier, James K.; Baker, David W. (eds.). Faith, Tradition, and History: Old Testament Historiography in Its Near Eastern Context. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-82-X.

- Chen, Fei (2020). Study on the Synchronistic King List from Ashur. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-43091-4.

- Düring, Bleda S. (2020). The Imperialisation of Assyria: An Archaeological Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-47874-8.

- Eppihimer, Melissa (2013). "Representing Ashur: The Old Assyrian Rulers' Seals and Their Ur III Prototype". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 72 (1): 35–49. doi:10.1086/669098. JSTOR 10.1086/669098. S2CID 162825616.

- Frahm, Eckart (2017). "The Neo-Assyrian Period (ca. 1000–609 BCE)". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-32524-7.

- Frahm, Eckart (2017). "Introduction". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-32524-7.

- Garfinkle, Steven J. (2007). "The Assyrians: A New Look at an Ancient Power". In Rubio, Gonzalo; Garfinkle, Steven J.; Beckman, Gary; Snell, Daniel C.; Chavalas, Mark W. (eds.). Current Issues and the Study of the Ancient Near East. Publications of the Association of Ancient Historians. Claremont: Regina Books. ISBN 978-1-930053-46-5.

- Lambert, W. G. (1983). "The God Aššur". Iraq. 45 (1): 82–86. doi:10.2307/4200181. JSTOR 4200181. S2CID 163337976.

- Lendering, Jona (2006). "The Assyrian King List". Livius. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- Lewy, Hildegard (1971). "Assyria c. 2600–1816 BC". In Edwards, I. E. S.; Gadd, C. J.; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume I Part 2: Early History of the Middle East (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07791-5.

- Luukko, Mikko; Van Buylaere, Greta (2017). "Languages and Writing Systems in Assyria". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-32524-7.

- Mallowan, Max E. L. (1971). "The Early Dynastic Period in Mesopotamia". In Edwards, I. E. S.; Gadd, C. J.; Hammond, N. G. L. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume I Part 2: Early History of the Middle East (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07791-5.

- Michel, Cécile (2017). "Economy, Society, and Daily Life in the Old Assyrian Period". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-32524-7.

- Van De Mieroop, Marc (2016). A History of the Ancient Near East (3rd ed.). Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

- Radner, Karen (2015). Ancient Assyria: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871590-0.

- Reade, J. E. (2001). "Assyrian King-Lists, the Royal Tombs of Ur, and Indus Origins". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 60 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1086/468883. JSTOR 545577. S2CID 161480780.

- de Ridder, Jacob Jan (2017). "Slavery in Old Assyrian Documents". In Kulakoğlu, Fikri; Barjamovic, Gojko (eds.). Subartu XXXIX: Kültepe International Meetings, Vol. II: Movement, Resources, Interaction. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. ISBN 978-2-503-57522-3.

- Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-012523-8.

- Veenhof, Klaas R. (2003). The Old Assyrian List of Year Eponyms from Karum Kanish and its Chronological Implications. Ankara: Turkish Historical Society. ISBN 979-975161546-5.

- Veenhof, Klaas R.; Eidem, Jesper (2008). Mesopotamia: The Old Assyrian Period. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis. Göttingen: Academic Press Fribourg. ISBN 978-3-7278-1623-9.

- Veenhof, Klaas R. (2017). "The Old Assyrian Period (20th–18th century BCE)". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-32524-7.

- Yamada, Shiego (2017). "The Transition Period (17th to 15th century BCE)". In E. Frahm (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-32524-7.