Rajasthani people

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 68,548,437 (2011)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Rajasthani, Hindi | |

| Religion | |

| Majority: Hinduism Minority: Islam and Jainism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Indo-Aryan peoples |

Rajasthani people or Rajasthanis are a group of Indo-Aryan peoples native to Rajasthan ("the land of kings"),[2] a state in Northern India. Their language, Rajasthani, is a part of the western group of Indo-Aryan languages.

History

| Part of a series on |

| Rajasthani people |

|---|

| Culture |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Notable people |

| Rajasthan Portal |

The first mention of the word Rajasthan comes from the works of George Thomas (Military Memories) and James Tod (Annals). Rajasthan literally means the Land of Kingdoms. However, western Rajasthan and eastern Gujarat were part of "Gurjaratra".[3] The local dialects of the time use the expression Rājwār, the place or land of kings, later Rajputana.[4][5]

Although the history of Rajasthan goes back as far as the Indus Valley civilisation, the foundation of the Rajasthani community took shape with the rise of Western Middle Kingdoms such as Western Kshatrapas. Western Kshatrapas (35-405 CE) were rulers of the western part of India (Saurashtra and Malwa: modern Gujarat, Southern Sindh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan). They were the successors to the Indo-Scythians who invaded the area of Ujjain and established the Saka era (with Saka calendar), marking the beginning of the long-lived Saka Western Satraps kingdom.[6] Saka calendar (also been adopted as Indian national calendar) is used by the Rajasthani community and adjoining areas such as Punjab and Haryana. With time, their social structures received stronger reorganisations, thus giving birth to several martial sub ethnic groups (previously called as Martial race but the term is now obsolete ). Rajasthanis emerged as major merchants during medieval India. Rajasthan was among the important centres of trade with Rome, eastern Mediterranean and southeast Asia.[7]

Romani people

Some claim that Romani people originated in parts of the Rajasthan. Indian origin was suggested based on linguistic grounds as early as 200 years ago.[8] The roma ultimately derives from a form ḍōmba ("man living by singing and music"), attested in Classical Sanskrit.[9] Linguistic and genetic evidence indicates the Romanies originated from the Indian subcontinent, emigrating from India towards the northwest no earlier than the 11th century.[citation needed] Contemporary populations sometimes suggested as sharing a close relationship to the Romani are the Dom people of Central Asia and the Banjara of India.[10]

Origin

Like other Indo-Aryan peoples, modern day Rajasthanis and their ancestors have inhabited Rajasthan since ancient times. The erstwhile state of Alwar, in north-eastern Rajasthan, is possibly the oldest kingdom in Rajasthan. Around 1500 BC, it formed a part of the Matsya territories of Viratnagar (present-day Bairat) encompassing Bharatpur, Dholpur, and Karauli.[11][better source needed]

Religion

Rajasthani society is a blend of predominantly Hindus with sizeable minorities of Muslims, Sikhs and Jains.

Hinduism

Shaivism and Vaishnavism is followed by majority of the people; however, Shaktism is followed in the form of Bhavani and her avatars are equally worshiped throughout Rajasthan.[12]

Meenas of Rajasthan till date strongly follow Vedic culture which usually includes worship of Bhainroon (Shiva) and Krishna as well as the Durga.[13]

The Charans worship various forms and incarnations of Shakti such as Hinglaj[14] or Durga, Avad Mata,[15] Karni Mata,[16] and Khodiyar.[17]

The Rajputs generally worship the Karni Mata, Sun, Shiva, Vishnu, and Bhavani (Goddess Durga).[18][19] Meerabai was an important figure who was devoted Krishna.

Bishnoi (also Vishnoi) is a stronge Vaishnava community which follow Vedic culture, found in the Western Thar Desert and northern parts of state and are devote followers of Vishnu and his consort Lakshami. They follow a set of 29 principles/commandments given by Sri Guru Jambheshwar (1451–1536) who founded the sect at Samrathal Dhora, Bikaner in 1485 and his teachings, comprising 120 shabads, are known as Shabadwani. As of 2019, there are an estimated 1500,000 Bishnoi residing in north and central India.[20]

The Gujars worship the Devnarayan, Shiva, and Goddess Bhavani.[21][22][23] Historically, the Gujars were Sun-worshipers and are described as devoted to the feet of the Sun-god.[23]

- Hinduism in Rajasthan

-

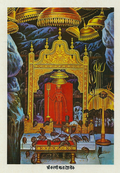

Shiva temple at Chittor Fort

-

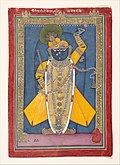

Krishna in the form of Shri Nathji

-

Bheruji Temple (Bhairava)

Islam

Rajasthani Muslims are predominantly Sunnis. They are mainly Meo, Mirasi, Khanzada, Qaimkhani, Manganiar, Muslim Ranghar, Merat, Sindhi-Sipahi, Rath, and Pathans.[24] Converts to Islam still maintained many of their earlier traditions. They share lot of socio-ritual elements. Rajasthani Muslim communities, after their conversion, continued to follow pre-conversion practices (Rajasthani rituals and customs) which is not the case in other parts of the country. This exhibits the strong cultural identity of Rajasthani people as opposed to religious identity.[25] According to 2001 census, Muslim population of Rajasthan is 4,788,227, accounting for around 9% of the total population.[26]

Other religions

Some other religions are also prevalent such as Buddhism, Christianity, Parsi religion and others.[19] Over time, there has been an increase in the number of followers of Sikh religion.[19] Though Buddhism emerged as a major religion during 321-184 BC in Mauryan Empire, it had no influence in Rajasthan for the fact that Mauryan Empire had minimal impact on Rajasthan and its culture.[27] Although Jainism is not that prevalent in Rajasthan today, Rajasthan and Gujarat areas were historically strong centres of Jainism in India.[28]

Castes and communities

Rajasthanis form an ethno-linguistic group that is distinct in its language, history, cultural and religious practices, social structure, literature, and art. However, there are many different castes and communities, with diversified traditions of their own. Major sub ethnic groups are Rajputs, Rajpurohits, Brahmans, Bishnois, Jats, Gurjars, Yadavs, Meenas, Berwas, Chamar, Charans, Meghwals, Malis, Kolis, Agrawals, Barnwals, Kumhars, Kumawat, etc.[29][30][31][32]

- Jats are traditionally a agricultural caste and are listed under Other Backward Class of Rajasthan State. In east Rajasthan Bharatpur[33] and Dholpur[34] were ruled by Jat rulers. Jats of these two districts were removed from central OBC list after a ruling by Supreme Court of India in 2015.[35] Rajasthan state government added them back in the state's other backward caste list but did not send the recommendation to central government, since they were removed by the Supreme Court.[36] Veer Tejaji is highly esteemed in Rajasthan as a folk deity and renowned for his bravery and status, he is frequently linked to the political and cultural narratives of the Jats.[37]

- Brahmin (alternately Brahman) are mostly Gaurs, Gurjar Gaurs, Paliwals, Dadheechs, Nagars, Vyasas, Pareeks, Rankawats,Audichya Brahmin, Saraswats, Sanadhyas, Shrimalis, Gargas, Abotis, Pushkarna Brahmins, Bhutia Brahmins. Brahmins, along with the Rajpurohit and Charan, are the only castes other than the Rajput who were granted jagirs in Rajasthan.[38]

- Rajputs are various patrilineal clans historically associated with warriorhood. An aristocratic class in Rajasthan, they are descendants of ancient ruling dynasties of the region. Rajput is a Forward or General caste in India except in the state of Karnataka where they are categoriesd as OBC Rajputs being a politically influential caste, they are categorised in Central Other Backward Class/OBC list by National Commission for Backward Classes[39][40] as well as Karnataka state Government's OBC list.[41]

- Rajpurohit is a caste with traditions similar to both Rajputs and Brahmins. They are the descendants of Saptrishis. They are engaged in diverse occupations like Gurus of Rajput kings, warriors, traders and jagirdars. Rajpurohit, along with the Brahmins and Charan, are the only castes other than the Rajput who were granted jagirs and were allowed to use the title thakur. Rajpurohits, Rajputs and Charan are considered to be identical for their political ideology.

- Charan is a caste engaging in diverse occupations like poets, litterateurs, as well as warriors, traders and jagirdars. Charan, along with the Brahmins, are the only castes other than the Rajput who were granted jagirs and were allowed to use the title thakur.[42][43][44]

- Sunar (alternately, Sonar or Swarnkar, Soni) is a community of people who work as goldsmiths.[45] The community is primarily Hindu, and found all over Rajasthan. The Sunar caste is in central[46][47][48] as well as the state[49] OBC list in Rajasthan.

- Bishnoi (also Vishnoi) is a Vaishnava community which follow Vedic culture and live in well organised social structure. Most of them are agricultural landowners, but many of them are opting for service sector. Also, Bishnois from south-western Rajasthan are business oriented people. Bishnois predominantly live the districts of Anupgarh, Sri Ganganagar, Hanumangarh, Bikaner, Jaisalmer, Barmer, Balotra, Sanchore, Jodhpur, Jodhpur rural, Phalodi, Pali but can also be found throughout Rajasthan in smaller numbers. They are categorised as a forward caste in all the states of India except in Rajasthan, where they are categorised under OBC.[49]

- Bania are the trading communities which includes Aggarwals, Barnwals, Khandelwals and Maheshwaris. Agarwals trace their origin to Agroha, a historic town near Hisar in Haryana and Barnwal (also spelled Baranwal, Burnwal, Varnwal, Warnwal or Barnawal) is an Indian toponymic Marwari surname from Baran in Rajasthan, India, while Khandelwal and Maheshwari communities are said to be originated from Khandela, near Jaipur. Baniya community is known for their excellent trading techniques and business acumen.

- Meghwal The Meghwal or Meghwar (also known as Megh and Meghraj) people live primarily in northwest India, with a small population in Pakistan. Their traditional occupation was agricultural farming.

- Khatik word is derived from the Sanskrit language word Khat. Khatik means "butcher". In ancient times the main profession of Khatik Caste was to slaughter and prepare sheep and goats. Found throughout India, the Khatik community began as hunters and butchers.

- Gurjars are historically, the Gujar caste is an animal rearing caste, this caste is included in the Backward Classes group in most of the states of India. They are also found in some states like Jammu and Kashmir and Himachal Pradesh in good number. They were added in criminal tribe by britishers for revolting against them in various parts which is one of the main reason they were left behind in education and this tribe is generally known for its bravery.

- Sain Nai mostly lives in Alwar, Dausa, Bharatpur, Jaipur & some other district of Rajasthan. They worship their kuldevi sati Narayani Mata (Temple in Alwar).[50]

- Seervi are mainly in agriculture business in Jodhpur and Pali District of Rajasthan. Major population of Seervi's are followers of Aai Mata which has main temple at Bilara. These days Seervi have migrated from Rajasthan to Southern part of India and became good business community.

- Kumawats are also found all over Rajasthan with majority in Jaipur, Pali, Bikaner, Jodhpur etc. . Kumawat are also called as Kheti Ghar Kumar as their main profession is related to agriculture and now even they are into business all over the country like Indore, Bangalore, Hyderabad, Chennai etc.

There are few other tribal communities in Rajasthan, such as Meena and Bhils. Meena ruled on Dhundhar near 10th century. The Ghoomar dance is one well-known aspect of Bhil tribe. Meena and Bhils were employed as soldiers by the Rajputs. During colonial rule, the British government declared 250 groups[51] which included Meenas, Gujars, etc.[52][53] as "criminal tribes". Any group or community that took arms and opposed British rule were branded as criminal by the British government in 1871.[54] This Act was repealed in 1952 by Government of India.[51] Sahariyas, the jungle dwellers, who are believed to be of Bhil origin, inhabit the areas of Kota, Dungarpur and Sawai Madhopur in the southeast of Rajasthan. Their main occupations include working as shifting cultivators, hunters and fishermen.[55][56] Garasias is a small Rajput tribe inhabiting Abu Road area of southern Rajasthan.[55][56]

There are a few other colourful folks, groups like those of Gadia Luhar, Banjara, Nat, Kalbelia, and Saansi, who criss-cross the countryside with their animals. The Gadia Luhars are said to be once associated with Maharana Pratap.[57]

Rajasthani literature

Scholars agree on the fact that during 10th-12th century, a common language was spoken in western Rajasthan and northern Gujarat. This language was known as Old Gujarati (1100 AD — 1500 AD) (also called Old Western Rajasthani, Gujjar Bhakha, Maru-Gurjar). The language derived its name from Gurjara and its people, who were residing and ruling in Punjab, Rajputana, central India, and various parts of Gujarat at that time.[58] It is said that Marwari and Gujarati has evolved from this Gurjar Bhakha later.[59] The language was used as a literary language as early as the 12th century. Poet Bhoja has referred to Gaurjar Apabhramsha in 1014 AD.[58] Formal grammar of Rajasthani was written by Jain monk and eminent scholar Hemachandra Suri in the reign of Chaulukya king Jayasimha Siddharaja. Rajasthani was recognised by the State Assembly as an official Indian language in 2004. Recognition is still pending from the government of India.[60]

First mention of Rajasthani literature comes from the 778 CE novel Kuvalayamala, composed in the town of Jalor in south-eastern Marwar by Jain acharya Udyotana Suri. Udyotan Suri referred it as Maru Bhasha or Maru Vani. Modern Rajasthani literature began with the works of Suryamal Misrana.[61] His most important works are the Vamsa Bhaskara and the Vira satsaī. The Vira satsaī is a collection of couplets dealing with historical heroes. Two other important poets in this traditional style are Bakhtavara Ji and Kaviraja Murari Dan. Apart from academic literature, there exists folk literature as well. Folk literature consists of ballads, songs, proverbs, folk tales, and panegyrics. The heroic and ethical poetry were the two major components of Rajasthani literature throughout its history. The development of Rajasthani literature, as well as virkavya (heroic poetry), from the Dingal language took form during the early formation of medieval social and political establishments in Rajasthan. Maharaja Chatur Singh (1879–1929) was a devotional poet from Mewar. His contributions were poetry style that was essentially a bardic tradition in nature. Another important poet was Hinglaj Dan Kaviya (1861–1948). His contributions are largely of the heroic poetry style.[62]

Developmental progression and growth of Rajasthani literature cand be divided into 3 stages[63]

| 900 to 1400 AD | The Early Period |

| 1400 to 1857 AD | Medieval Period |

| 1857 to present day | Modern Period |

Culture and tradition

Dress

Traditionally men wear earrings, apadravya, moustaches, dhotis, kurta, angarkha, and paggar or safa (headgear resembling a turban)( Safa wearing style,colour,etc. vary by caste, age factors,etc)(Different styles of Safa). Traditional chudidar payjama (puckered trousers) frequently replaces dhoti in different regions. Women wear dress according to their caste culture. Poshak is worn by Rajput, Rajpurohit and Charan women only(As per tradition). However, dress style changes with lengths and breaths of vast Rajasthan. Dhoti is worn in different ways in Marwar (Jodhpur area) or Shekhawati (Jaipur area) or Hadoti (Bundi area). Similarly, there are a few differences pagri and safa despite both being Rajasthani headgear. Mewar has the tradition of paggar, whereas Marwar has the tradition of safa.

Rajasthan is also famous for its amazing ornaments. From ancient times, Rajasthani people have been wearing jewellery of various metals and materials. Traditionally, women wore Gems-studded gold and silver ornaments. Historically, silver or gold ornaments were used for interior decoration stitched on curtains, seat cushions, handy-crafts, etc. Wealthy Rajasthanis used Gems-studded gold and silver on swords, shields, knives, pistols, cannon, doors, thrones, etc., which reflects the importance of ornaments in lives of Rajasthanis.[64]

Cuisine

Rich Rajasthani culture reflects in the tradition of hospitality which is one of its own kind. Rajasthan region varies from arid desert districts to the greener eastern areas. Varying degree of geography has resulted in a rich cuisine involving both vegetarian and non vegetarian dishes. Rajasthani food is characterised by the use of Jowar, Bajri, legumes and lentils, its distinct aroma and flavor achieved by the blending of spices including curry leaves, tamarind, coriander, ginger, garlic, chili, pepper, cinnamon, cloves, cardamom, cumin, and rosewater.

The major crops of Rajasthan are jowar, bajra, maize, ragi, rice, wheat, barley, gram, tur, pulses, ground nut, sesamum, etc. Millets, lentils, and beans are the most basic ingredients in food.

The majority of Hindu and Jain Rajasthanis are vegetarian. Rajasthani Jains do not eat after sundown and their food does not contain garlic and onions. Rajputs are usually meat eaters; however, eating beef is a taboo within the majority of the culture.[65][66]

Rajasthani cuisine has many varieties, varying regionally between the arid desert districts and the greener eastern areas. The most famous dish is Dal-Baati-Churma. It is a little bread full of clarified butter roasted over hot coals and served with a dry, flaky sweet made of gram flour, and Ker-Songri made with a desert fruit and beans.

Art

Music

Rajasthani Music has a diverse collection of musicians. Major schools of music includes Udaipur, Jodhpur, and Jaipur. Jaipur is a major Gharanas which is well known for its reverence for rare ragas. Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana is associated with Alladiya Khan (1855–1943), who was among the great singers of the late 19th and early 20th century. Alladiya Khan was trained both in Dhrupad and Khyal styles, though his ancestors were Dhrupad singers.[67] The most distinguishing feature of Jaipur Gharana is its complex and lilting melodic form.

Rajasthani paintings

The colourful tradition of Rajasthani people reflects in art of paintings as well. This painting style is called Maru-Gurjar painting. It throws light on the royal heritage of ancient Rajasthan. Under the Royal patronage, various styles of paintings developed, cultivated, and practised in Rajasthan, and painting styles reached their pinnacle of glory by 15th to 17th centuries. The major painting styles are phad paintings, miniature paintings, kajali paintings, gemstone paintings, etc. There is incredible diversity and imaginative creativity found in Rajasthani paintings. Major schools of art are Mewar, Marwar, Kishangarh, Bundi, Kota, Jaipur, and Alwar.

Development of Maru-Gurjar painting[68]

- Western Indian painting style - 700 AD

- Mewar Jain painting style - 1250 AD

- Blend of Sultanate Maru-Gurjar painting style - 1550 AD

- Mewar, Marwar, Dhundar, and Harothi styles - 1585 AD

Phad paintings ("Mewar-style of painting") is the most ancient Rajasthani art form. Phad paintings, essentially a scroll painting done on cloth, are beautiful specimen of the Indian cloth paintings. These have their own styles and patterns and are very popular due to their vibrant colours and historic themes. The Phad of God Devnarayan is largest among the popular Pars in Rajasthan. The painted area of God Devnarayan Ki Phad is 170 square feet (i.e. 34' x 5').[69] Some other Pars are also prevalent in Rajasthan, but being of recent origin, they are not classical in composition.[69] Another famous Par painting is Pabuji Ki Phad. Pabuji Ki Phad is painted on a 15 x 5 ft. canvas.[69] Other famous heroes of Phad paintings are Gogaji, Prithviraj Chauhan, Amar Singh Rathore, etc.[70]

Architecture

-

Interior shows stone work Adisvara temple

-

Jain temple at Ranakpur

-

Nagda Temple

-

Dev Somnath Temple

The rich tradition of Rajasthanis also reflect in the architecture of the region. There is a connecting link between Māru-Gurjara architecture and Hoysala temple architecture. In both of these styles, architecture is treated sculpturally.[71]

Occupation

Agriculture is the main occupation of Rajasthani people in Rajasthan. Major crops of Rajasthan are jowar, bajri, maize, ragi, rice, wheat, barley, gram, tur, pulses, ground nut, sesamum, etc. Agriculture was the most important element in the economic life of the people of medieval Rajasthan.[72] In early medieval times, the land that could be irrigated by one well was called Kashavah, which is a land that could be irrigated by one Knsha or leather bucket.[73] Historically, there were a whole range of communities in Rajasthan at different stages of economy, from hunting to settled agriculture. The Van Baoria, Tirgar, Kanjar, vagri, etc. were traditionally hunters and gatherers. Now, only the Van Baoria are hunters, while others have shifted to agriculture related occupations.[74] There are a number of artisans, such as Lohar and Sikligar. Lohar are blacksmiths while Sikligar do specific work of making and polishing of arms used in war. Now, they create tools used for agriculture.

Trade and business

Historically, Rajasthani business community (famously called Marwaris, Rajasthani: मारवाड़ी) conducted business successfully throughout India and outside of India. Their business was organised around the "joint-family system", in which the grandfather, father, sons, their sons, and other family members or close relatives worked together and shared responsibilities of business work.[75] The success of Rajasthanis in business, that too outside of Rajasthan, is the outcome of feeling of oneness within the community.[citation needed] Rajasthanis tend to help community members, and this strengthens the kinship bondage, oneness, and trust within community. Another fact is that they have the ability to adapt to the region they migrate. They assimilate with others so well and respect the regional culture, customs, and people.[76] It is a rare and most revered quality for any successful businessman. Today, they are among the major business classes in India. The term Marwari has come to mean a canny businessman from the State of Rajasthan. The Bachhawats, Birlas, Goenkas, Bajajs, Ruias, Piramels and Singhanias are among the top business groups of India. They are the famous marwaris from Rajasthan.[77]

Diaspora

The Marwari group of Rajasthanis have a substantial diaspora throughout India, where they have been established as traders.[78] Marwari migration to the rest of India is essentially a movement in search of opportunities for trade and commerce. In most cases, Rajasthanis migrate to other places as traders.[79]

Maharashtra

In Maharashtra (an ancient Maratha Desh), Rajasthanis are mainly merchants and own large to mid-sized business houses. Maheshwaris are mainly Hindus (some are also Jains), who migrated from Rājputāna in the olden days. They usually worship all Gods and Goddesses along with their village deities.[80]

Seervi

The Seervi are a khardiya rajput, living in the Marwar and Gorwar region of Rajasthan. Later this caste is found in greater numbers in Jodhpur and Pali districts of Rajasthan.The sirvis are followers of Aai Mataji. The Servi Clan is considered to be in front of the Rajput caste. Servi is a Kshatriya farming caste which was separated from the Rajputs about 800 years ago and was living in the Marwar and Gaudwar region of Rajasthan.[81]

Images

-

Carved elephants on the walls of Jagdish Temple that was built by Maharana Jagat Singh Ist in 1651 A.D.

-

The region surrounding Aravalli hills near Ranthambore, Rajasthan, India.

-

Detailed stone work, Karni Mata Temple, Bikaner Rajasthan.

-

Marble stone work, Jaisalmer Jain Temple, Rajasthan.

-

Seated Ganesha, sandstone sculpture from Rajasthan, India, 9th century, Honolulu Academy of Arts.

-

Yellow sandstone sculpture of a standing deity, 11th century CE, Rajasthan.

-

Armor coat, 18th century, Rajasthan.

-

Marble sculpture of a female, ca 1450, Rajasthan.

-

Bani Thani painting, Rajasthan.

-

Camel ride in sand dunes, Thar desert, Jaisalmer.

See also

References

- ^ https://apfstatic.s3.ap-south-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/Rajasthan_0.pdf?YvBqKD65v6PMQYrPTcZWuRzuqZNg1nww [bare URL]

- ^ The Territories and States of India By Tara Boland-Crewe, David Lea, pg 208

- ^ Ramesh Chandra Majumdar; Achut Dattatrya Pusalker, A. K. Majumdar, Dilip Kumar Ghose, Vishvanath Govind Dighe, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan (1977). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The classical age. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 153

- ^ R.K. Gupta; S.R. Bakshi (1 January 2008). Studies In Indian History: Rajasthan Through The Ages The Heritage Of Rajputs (Set Of 5 Vols.). Sarup & Sons. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-81-7625-841-8. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ John Keay (2001). India: a history. Grove Press. pp. 231–232. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0.

- ^ "The dynastic art of the Kushans, John Rosenfield, p 130

- ^ A brief history of India By Judith E. Walsh,43

- ^ Fraser, Angus (1 February 1995). Gypsies (Peoples of Europe) (2nd ed.). Blackwell, Oxford. ISBN 978-0-631-19605-1.

- ^ Cf. Ralph L. Turner, A comparative dictionary of the Indo-Aryan languages, p. 314. London: Oxford University Press, 1962-6.

- ^ Hancock, Ian (2002). Ame Sam e Rromane Džene/We are the Romani people. Univ of Hertfordshire Press. p. 13. ISBN 1-902806-19-0.

- ^ /de/India/rajasthan-people-society.aspx

- ^ The Jains By Paul Dundas, Pg 148

- ^ Kishwar, Madhu (1994). Codified Hindu Law. Myth and Reality. Economics and political weekly,.

- ^ Kothiyal, Tanuja (14 March 2016). Nomadic Narratives: A History of Mobility and Identity in the Great Indian Desert. Cambridge University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-107-08031-7.

Charans regard themselves as devotees of a goddess named Hinglaj, a mahashakti, who herself was a Charani born to Charan Haridas of Gaviya lineage in Nagar Thatta.

- ^ Müller, Friedrich Max (1973). German Scholars on India: Contributions to Indian Studies. Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office. p. 390.

This Avad is believed to be an incarnation of the mother and stands second in the Charan worship, the first being Durga.

- ^ Prabhākara, Manohara (1976). A Critical Study of Rajasthani Literature, with Exclusive Reference to the Contribution of Cāraṇas. Panchsheel Prakashan.

Karni : Presiding Deity of Rajputs and Cāraņas

- ^ Padma, Sree (3 July 2014). Inventing and Reinventing the Goddess: Contemporary Iterations of Hindu Deities on the Move. Lexington Books. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-7391-9002-9.

For Charans, Khodiyar is the kuldevi for obvious reasons. In her iconic images, her attire—long skirt, long jacket, and a scarf covering her head and front of the jacket—clearly reflects her Charan identity.

- ^ Schaflechner, Jürgen (2018). Hinglaj Devi: Identity, Change, and Solidification at a Hindu Temple in Pakistan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-085052-4.

Among the crowds are many Rajputs who link their community's existence, or survival, to the help of Karni Mata.

- ^ a b c "Our People". Government of Rajasthan. Archived from the original on 7 February 2008.

- ^ Akash Kapur, A Hindu Sect Devoted to the Environment, New York Times, 8 October 2010.

- ^ Daniel Neuman; Shubha Chaudhuri; Komal Kothari (2007). Bards, ballads and boundaries: an ethnographic atlas of music traditions in West Rajasthan. Seagull. ISBN 978-1-905422-07-4.

Devnarayan is worshiped as an avatar or incarnation of Vishnu. This epic is associated with the Gujar caste

- ^ Indian studies: past & present, Volume 11. Today & Tomorrow's Printers & Publishers. 1970. p. 385.

The Gujars of Punjab, North Gujarat and Western Rajasthan worship Sitala and Bhavani

- ^ a b Lālatā Prasāda Pāṇḍeya (1971). Sun-worship in ancient India. Motilal Banarasidass. p. 245.

- ^ Muslim Communities of Rajasthan, ISBN 1-155-46883-X, 9781155468839

- ^ Rajasthan, Volume 1 By K. S. Singh, B. K. Lavanta, Dipak Kumar Samanta, S. K. Mandal, Anthropological Survey of India, N. N. Vyas, p 19

- ^ Indian Census 2001 – Religion Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Land and people of Indian states and union territories:Rajasthan by Gopal K. Bhargava, Shankarlal C. Bhatt, p 18

- ^ Jainism: the world of conquerors, Volume 1 By Natubhai Shah, p 68

- ^ "Rajasthan polls: It's caste politics all the way - Times of India". The Times of India.

- ^ "Rajasthan's castes were first classified by British - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ "In poll battle for Rajasthan, BJP fights Rajput woes". The Economic Times. 30 November 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ "Rajput population in Rajasthan - Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ Pradhan, Ram Chandra (1985). Colonialism in India: Roots of Underdevelopment. Prabhat Prakashan. ISBN 9789352664344.

- ^ Rizvi, S. H. M. (1987). Mina, the Ruling Tribe of Rajasthan: Socio-biological Appraisal. B.R. Publishing Corporation. p. 29. ISBN 9788170184478.

- ^ Khan, Hamza (19 November 2020). "Rajasthan: Jats seek central OBC quota, threaten stir". The Indian Express. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "Jats of Two Rajasthan Districts Demand Reservation Under Central OBC Quota". The Wire. 20 November 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ^ "Veer Tejaji Maharaj: वीर तेजाजी महाराज की वो अमर गाथा जिसके चलते वो बन गए जाट समाज के आराध्य देव". Zee News Hindi (in Hindi). Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ Saksena, B. S. (1965). "The Phenomenon Of Feudal Loyalty : A Case Study In Sirohi State". The Indian Journal of Political Science. 26 (4): 121–128. ISSN 0019-5510. JSTOR 41854129.

Among jagirdars, all were not Rajputs. Jagirs were also granted to Charans and Brahmins. They were also known as thakurs.

- ^ "Central OBC list, Karnataka". National Commission for Backward Classes. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ "PDF - National OBC list for Karnataka" (PDF).

- ^ "CASTE LIST Government Order No.SWD 225 BCA 2000, Dated:30th March 2002". KPSC. Karnataka Government. Archived from the original on 20 September 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ Palriwala, Rajni (1993). "Economics and Patriliny: Consumption and Authority within the Household". Social Scientist. 21 (9/11): 47–73. doi:10.2307/3520426. ISSN 0970-0293. JSTOR 3520426.

Charans are a caste peculiar to Gujarat and Rajasthan and their ranking is controversial. In Rajasthan, they were bards and 'literateurs', but also warriors and jagirdars, holders of land and power over men; the dependents of Rajputs, their equals and their teachers. There were no Rajputs in this village, though one of my original criteria in selecting a study village was the presence of Rajputs. On my initial visit and subsequently, I was assured of this fact vis-a-vis Panchwas and introduced to the thakurs, who in life-style, the practice of female seclusion, and various reference points they alluded to appeared as Rajputs. While other villagers insisted that Rajputs and Charans were all the same to them, the Charans, were not trying to pass themselves off as Rajputs, but indicating that they were as good as Rajputs if not ritually superior.

- ^ Saksena, B. S. (1965). "The Phenomenon Of Feudal Loyalty : A Case Study In Sirohi State". The Indian Journal of Political Science. 26 (4): 121–128. ISSN 0019-5510. JSTOR 41854129.

Among jagirdars, all were not Rajputs. Jagirs were also granted to Charans and Brahmins. They were also known as thakurs.

- ^ Transaction and Hierarchy: Elements for a Theory of Caste. Routledge. 9 August 2017. ISBN 978-1-351-39396-6.

Charans received lands in jagir for their services, and in parts of Marwar, certain Charan families were effectively Darbars.

- ^ People of India: Uttar Pradesh (Volume XLII) edited by A Hasan & J C Das page 1500 to 150

- ^ "National Commission for Backward Classes". www.ncbc.nic.in.

- ^ "National Commission for Backward Classes" (PDF). www.ncbc.nic.in. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "National Commission for Backward Classes" (PDF). www.ncbc.nic.in. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ a b "List of Caste OBC". Government of Rajasthan Social Justice and Empowerment Department. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ Jibraeil: "Position of Jats in Churu Region", The Jats - Vol. II, Ed Dr Vir Singh, Delhi, 2006, p. 223

- ^ a b The Indian constitution--: a case study of backward classes by Ratna G. Revankar, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1971, pp.239

- ^ (India), Rajasthan (1968). "Rajasthan [district Gazetteers].: Alwar".

{cite journal}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Sen, Snigdha (1992). The historiography of the Indian revolt of 1857. Punthi-Pustak. ISBN 978-81-85094-52-6.

- ^ J. J. Roy Burman (2010). Ethnography of a denotified tribe: the Laman Banjara. Mittal Publications. p. 8. ISBN 978-81-8324-345-2.

- ^ a b "Rajasthan Tribes - Tribes of Rajasthan India - Rajasthan Tribals".

- ^ a b "Tribal Areas of Rajasthan - Villages of Rajasthan". www.travel-in-rajasthan.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2006.

- ^ Merlin A. Taber; Sushma Batra (1996). Social strains of globalization in India: case examples. New Concepts. p. 152.

- ^ a b K. Ayyappapanicker (1997). Medieval Indian literature: an anthology, Volume 3. Sahitya Akademi. p. 91. ISBN 978-81-260-0365-5.

- ^ Ajay Mitra Shastri; R. K. Sharma; Devendra Handa (2005). Revealing India's past: recent trends in art and archaeology. Aryan Books International. p. 227. ISBN 978-81-7305-287-3.

It is an established fact that during 10th-11th century.....Interestingly the language was known as the Gujjar Bhakha..

- ^ Casting Kings: Bards and Indian Modernity by JEFFREY G. SNODGRASS, p 20

- ^ Suryamal Misrama:britannica

- ^ History of Indian Literature: .1911-1956, struggle for freedom By Sisir Kumar Das, p 188

- ^ Medieval Indian literature: an anthology, Volume 3 By K. Ayyappapanicker, Sahitya Akademi, p 454

- ^ Rajasthan, Part 1 By K. S. Singh, p 15

- ^ Naravane, M. S. (1999). The Rajputs of Rajputana: a glimpse of medieval Rajastha. APH Publishing. pp. 184(see pages 47–50). ISBN 9788176481182.

- ^ Serving Empire, Serving Nation by Glenn J. Ames, The University of Toledo, Pg 26

- ^ Tradition of Hindustani music By Manorma Sharma, p 49

- ^ Art and artists of Rajasthan by R.K. Vaśishṭha

- ^ a b c Painted Folklore and Folklore Painters of India. Concept Publishing Company. 1976.

- ^ Indian Murals and Paintings By Nayanthara S, p 15

- ^ The legacy of G.S. Ghurye: a centennial festschrift By Govind Sadashiv Ghurye, A. R. Momin, p-205

- ^ Rajasthan through the Ages the Heritage of By R.K. Gupta, p 56

- ^ Rajasthan studies by Gopi Nath Sharma

- ^ Rajasthan, Volume 1, Anthropological Survey of India, p 19

- ^ The rise of business corporations in India By Shyam Rungta, p 165

- ^ Business history of India By Chittabrata Palit, Pranjal Kumar Bhattacharyya, p 278, 280

- ^ History, Religion and Culture of India By S. Gajrani

- ^ Singh, Lavania, Samanta, Mandal, Vyas (1998). People of India: Rajasthan. Popular Prakashan. p. xxvii-xxviii. ISBN 978-81-7154-769-2.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Business history of India By Chittabrata Palit, Pranjal Kumar Bhattacharyya, p 280

- ^ People of India: Maharashtra, Volume 2 By Kumar Suresh Singh, B. V. Bhanu, Anthropological Survey of India

- ^ "PeopleGroups.org - Sirvi of India". Peoplegroups.org. Retrieved 3 March 2022.[permanent dead link]

External links

- People of Rajasthan Government of Rajasthan

- Some Myths that every Rajasthani has to deal in rest of the part of India People from Rajasthan migrate to different parts of India for the purpose of business, work, Education etc. and during their stay outside they experience various myths about their native place that are prevalent in the rest of India. Those myths are clarified here with reasons.

- "Jaisalmer Ayo! Gateway of the Gypsies" sheds light on the lifestyle, culture and politics of nomadic life in Rajasthan as it followsa group of snake charmers, storytellers, musicians, dancers and blacksmiths as they make their way across the Thar Desert to Jaisalmer.