Rajasthani language

| Rajasthani | |

|---|---|

| राजस्थानी રાજસ્થાની | |

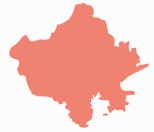

| Geographic distribution | Rajasthan, Malwa (MP) |

| Ethnicity | Rajasthanis |

Native speakers | 46 million[a][1] (2011 census)[1] |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | raja1256 |

| |

The Rajasthani languages are a branch of Western Indo-Aryan languages. They are spoken primarily in Rajasthan and Malwa, and adjacent areas of Haryana, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh in India. They have also reached different corners of India, especially eastern and southern parts of India, due to the migrations of people of the Marwari community who use them for internal communication.[3][4] There are also speakers in the Pakistani provinces of Punjab and Sindh. Rajasthani languages are also spoken to a lesser extent in Nepal, where they are spoken by 25,394 people according to the 2011 Census of Nepal.[5]

The term Rajasthani is also used to refer to a literary language mostly based on Marwari.[6]: 441

Geographical distribution

Most of the Rajasthani languages are chiefly spoken in the state of Rajasthan but are also spoken in Gujarat, Western Madhya Pradesh i.e. Malwa and Nimar, Haryana and Punjab. Rajasthani languages are also spoken in the Bahawalpur and Multan sectors of the Pakistani provinces of Punjab and Tharparkar district of Sindh. A distribution of the geographical area can be found in 'Linguistic Survey of India' by George A. Grierson.

Speakers

Standard Rajasthani or Standard Marwari, a version of Rajasthani, the common lingua franca of Rajasthani people and is spoken by over 25 million people (2011) in different parts of Rajasthan.[7] It has to be taken into consideration, however, that some speakers of Standard Marwari are conflated with Hindi speakers in the census. Marwari, the most spoken Rajasthani language with approximately 8 million speakers[7] situated in the historic Marwar region of western Rajasthan.

Classification

The Rajasthani languages belong to the Western Indo-Aryan language family. However, they are controversially conflated with the Hindi languages of the Central-Zone in the Indian national census, among other places[citation needed]. The main Rajasthani subgroups are:[8]

Languages and dialects

| Language[12] | ISO 639-3 | Scripts | No. of speakers[citation needed] | Geographical distribution[citation needed] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rajasthani | raj | Devanagari; previously Mandya;

Mahajani |

25,810,000[13] | Western and Northern part of Rajasthan |

| Marwari | mwr | Devanagari | 7,832,000 | Marwar region of Western Rajasthan |

| Malvi | mup | Devanagari | 5,213,000 | Malva region of Madhya Pradesh radesh and Rajasthan |

| Mewari | mtr | Devanagari | 4,212,000 | Mewar region of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh |

| Wagdi | wbr | Devanagari | 3,394,000 | Dungarpur and Banswara districts of Southern Rajasthan |

| Lambadi | lmn | Devanagari, Kannada script,

Telugu script |

4,857,819 | Banjaras of Maharashtra, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh |

| Hadauti | hoj | Devanagari | 2,944,000 | Hadoti region of southeastern Rajasthan |

| Nimadi | noe | Devanagari | 2,309,000 | Nimar region of west-central India within the state of Madhya Pradesh |

| Bagri | bgq | Devanagari, | 1,657,000 | Bagar region of Rajasthan, Punjab & Haryana.

In Rajasthan: Nohar-Bhadra, Anupgarh district, Hanumangarh district, Northern & Dungargarh tehsils of Bikaner district and Sri Ganganagar district; Taranagar, Sidhmukh, Rajgarh, Sardarshahar, Ratangarh, Bhanipura tehsils of Churu district, In Haryana: Sirsa district, Fatehabad district, Hisar district, Bhiwani district, Charkhi-dadri district, In Punjab: Fazilka district & Southern Muktsar district. |

| Ahirani | ahr | Devanagari | 1,636,000 | Khandesh region of north-west Maharashtra and also in Gujarat |

| Dhundhari | dhd | Devanagari | 1,476,000 | Dhundhar region of northeastern Rajasthan Jaipur, Sawai Madhopur, Dausa, Tonk and some parts of Sikar and karauli district |

| Gujari | gju | Takri, Pasto-Arabic | 122,800 | Northern parts of India and Pakistan as well as in Afghanistan |

| Dhatki | mki | Devanagri, Mahajani, Arabic | 210,000 | Pakistan and India (Jaisalmer and Barmer districts of Rajasthan and Tharparkar and Umerkot districts of Sindh) |

| Shekhawati | swv | Devanagari | 3,000,000 | the Shekhawati region of Rajasthan which comprises the southern Churu, Jhunjhunu, Neem-Ka-Thana and Sikar districts. |

| Godwari | gdx | Devanagari, Gujarati | 3,000,000 | Pali and Sirohi districts of Rajasthan and Banaskantha district of Gujarat. |

| Bhoyari/Pawari | Devanagari | 15,000-20,000 | Betul, Chhindwara, and Pandhurna districts of Madhya Pradesh, as well as Wardha district of Maharashtra.

It is exclusively spoken by the Pawar Rajputs (Bhoyar Pawar) who have migrated from Rajasthan and Malwa to Satpura and Vidarbha regions. | |

| Sahariya | Devanagari |

Official status

George Abraham Grierson (1908) was the first scholar who gave the designation 'Rajasthani' to the language, which was earlier known through its various dialects.

India's National Academy of Literature, the Sahitya Akademi,[14] and University Grants Commission recognize Rajasthani as a distinct language, and it is taught as such in Bikaner's Maharaja Ganga Singh University, Jaipur's University of Rajasthan, Jodhpur's Jai Narain Vyas University, Kota's Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University and Udaipur's Mohanlal Sukhadia University. The state Board of Secondary Education included Rajasthani in its course of studies, and it has been an optional subject since 1973. National recognition has lagged, however.[15]

In 2003, the Rajasthan Legislative Assembly passed a unanimous resolution to insert recognition of Rajasthani into the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India.[16] In May 2015, a senior member of the pressure group Rajasthani Bhasha Manyata Samiti said at a New Delhi press conference: "Twelve years have passed, but there has absolutely been no forward movement."[17]

All 25 Members of Parliament elected from Rajasthan state,[17] as well as former Chief Minister, Vasundhara Raje Scindia,[18] have also voiced support for official recognition of the language.[19]

In 2019 Rajasthan Government included Rajasthani as a language subject in state's open school system.[20]

A committee was formed by the Government in March 2023 to make Rajasthani an official language of the state after huge protests by the youths of Rajasthani Yuva Samiti.[21][22][23]

Grammar

Rajasthani is a head-final, or left-branching language. Adjectives precede nouns, direct objects come before verbs, and there are postpositions. The word order of Rajasthani is SOV, and there are two genders and two numbers.[24] There are no definite or indefinite articles. A verb is expressed with its verbal root followed by suffixes marking aspect and agreement in what is called a main form, with a possible proceeding auxiliary form derived from to be, marking tense and mood, and also showing agreement. Causatives (up to double) and passives have a morphological basis. It shares a 50%-65% lexical similarity with Hindi (this is based on a Swadesh 210 word list comparison). It has many cognate words with Hindi. Notable phonetic correspondences include /s/ in Hindi with /h/ in Rajasthani. For example /sona/ 'gold' (Hindi) and /hono/ 'gold' (Marwari). /h/ sometimes elides. There are also a variety of vowel changes. Most of the pronouns and interrogatives are, however, distinct from those of Hindi.[25]

- Use of retroflex consonants

The phonetic characteristics of Vedic Sanskrit, surviving in Rajasthani language, is the series of "retroflex" or "cerebral" consonants, ṭ (ट), ṭh (ठ), ḍ (ड), ḍh (ढ), and ṇ (ण). These to the Indians and Rajasthani are quite different from the "dentals", t (त), th (थ), d (द), dh (ध), n (न) etc. though many Europeans find them hard to distinguish without practice as they are not common in European languages. The consonant ḷ(ळ) is frequently used in Rajasthani, which also occurs in vedic and some prakrits, is pronounced by placing the tongue on the top of the hard palate and flapping it forward. In common with most other Indo-Iranian languages, the basic sentence typology is subject–object–verb. On a lexical level, Rajasthani has perhaps a 50 to 65 percent overlap with Hindi, based on a comparison of a 210-word Swadesh list. Most pronouns and interrogative words differ from Hindi, but the language does have several regular correspondences with, and phonetic transformations from, Hindi. The /s/ in Hindi is often realized as /h/ in Rajasthani – for example, the word 'gold' is /sona/ (सोना) in Hindi and /hono/ (होनो) in the Marwari dialect of Rajasthani. Furthermore, there are a number of vowel substitutions, and the Hindi /l/ sound (ल) is often realized in Rajasthani as a retroflex lateral /ɭ/ (ळ).

Phonology

Rajasthani has 11 vowels and 38 consonants. The Rajasthani language Bagri has developed three lexical tones: low, mid and high.[26]

Morphology

Rajasthani has two numbers and two genders with three cases. Postpositions are of two categories, inflexional and derivational. Derivational postpositions are mostly omitted in actual discourse.[27]

Syntax

- Rajasthani belongs to the languages that mix three types of case marking systems: nominative – accusative: transitive (A) and intransitive (S) subjects have similar case marking, different from that of transitive object (O); absolutive-ergative (S and O have similar marking, different from A), tripartite (A, S and O have different case marking). There is a general tendency existing in the languages with split nominal systems: the split is usually conditioned by the referents of the core NPs, the probability of ergative marking increasing from left to right in the following nominal hierarchy: first person pronouns – second person pronouns – demonstratives and third person pronouns – proper nouns – common nouns (human – animate – inanimate).[28] Rajasthani split case marking system partially follows this hierarchy:first and second person pronouns have similar A and S marking, the other pronouns and singular nouns are showing attrition of A/S opposition.

- Agreement: 1. Rajasthani combines accusative/tripartite marking in nominal system with consistently ergative verbal concord: the verb agrees with both marked and unmarked O in number and gender (but not in person — contrast Braj). Another peculiar feature of Rajasthani is the split in verbal concord when the participial component of a predicate agrees with O-NP while the auxiliary verb might agree with A-NP. 2. Stative participle from transitive verbs may agree with the Agent. 3. Honorific agreement of feminine noun implies masculine plural form both in its modifiers and in the verb.

- In Hindi and Punjabi only a few combinations of transitive verbs with their direct objects may form past participles modifying the Agent: one can say in Hindi:'Hindī sīkhā ādmī' – 'a man who has learned Hindi' or 'sāṛī bādhī aurāt' – 'a woman in sari', but *'kitāb paṛhā ādmī 'a man who has read a book' is impossible. Semantic features of verbs whose perfective participles may be used as modifiers are described in (Dashchenko 1987). Rajasthani seems to have less constrains on this usage, compare bad in Hindi but normal in Rajasthani.

- Rajasthani has retained an important feature of ergative syntax lost by the other representatives of Modern Western New Indo-Aryan (NIA), namely, the free omission of Agent NP from the perfective transitive clause.

- Rajasthani is the only Western NIA language where the reflexes of Old Indo-Aryan synthetic passive have penetrated into the perfective domain.

- Rajasthani as well as the other NIA languages shows deviations from Baker's 'mirror principle', that requires the strict pairing of morphological and syntactic operations (Baker 1988). The general rule is that the 'second causative' formation implies a mediator in the argument structure. However, some factors block addition of an extra agent into the causative construction.

- In the typical Indo-Aryan relative-correlative construction the modifying clause is usually marked by a member of the "J" set of relative pronouns, adverbs and other words, while the correlative in the main clause is identical with the remote demonstrative (except in Sindhi and in Dakhini). Gujarati and Marathi frequently delete the preposed "J" element. In Rajasthani the relative pronoun or adverb may also be deleted from the subordinate clause but – as distinct from the neighbouring NIA – relative pronoun or adverb may be used instead of correlative.

- Relative pronoun 'jakau' may be used not only in relative/correlative constructions, but also in complex sentences with "cause/effect" relations.[29]

Vocabulary

Categorisation and sources

These are the three general categories of words in modern Indo-Aryan: tadbhav, tatsam, and loanwords.[30]

Tadbhav

tadbhava, "of the nature of that". Rajasthani is a modern Indo-Aryan language descended from Sanskrit (old Indo-Aryan), and this category pertains exactly to that: words of Sanskritic origin that have demonstratively undergone change over the ages, ending up characteristic of modern Indo-Aryan languages specifically as well as in general. Thus the "that" in "of the nature of that" refers to Sanskrit. They tend to be non-technical, everyday, crucial words; part of the spoken vernacular. Below is a table of a few Rajasthani tadbhav words and their Old Indo-Aryan sources:

| Old Indo-Aryan | Rajasthani | Ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | ahám | hũ | [31] | |

| falls, slips | khasati | khisaknũ | to move | [32] |

| causes to move | arpáyati | ārpanũ | to give | [33] |

| attains to, obtains | prāpnoti | pāvnũ | [34] | |

| tiger | vyāghrá | vāgh | [35] | |

| equal, alike, level | samá | shamũ | right, sound | [36] |

| all | sárva | sau/sāb | [37] | |

Tatsam

tatsama, "same as that". While Sanskrit eventually stopped being spoken vernacularly, in that it changed into Middle Indo-Aryan, it was nonetheless standardised and retained as a literary and liturgical language for long after. This category consists of these borrowed words of (more or less) pure Sanskrit character. They serve to enrich Gujarati and modern Indo-Aryan in its formal, technical, and religious vocabulary. They are recognisable by their Sanskrit inflections and markings; they are thus often treated as a separate grammatical category unto themselves.

| Tatsam | English | Rajasthani |

|---|---|---|

| lekhak | writer | lakākh |

| vijetā | winner | vijetā |

| vikǎsit | developed | vikǎsāt |

| jāgǎraṇ | awakening | jāgān |

Many old tatsam words have changed their meanings or have had their meanings adopted for modern times. prasāraṇ means "spreading", but now it is used for "broadcasting". In addition to this are neologisms, often being calques. An example is telephone, which is Greek for "far talk", translated as durbhāṣ. Most people, though, just use phon and thus neo-Sanskrit has varying degrees of acceptance.

So, while having unique tadbhav sets, modern IA languages have a common, higher tatsam pool. Also, tatsams and their derived tadbhavs can also co-exist in a language; sometimes of no consequence and at other times with differences in meaning:

| Tatsam | Tadbhav | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| karma | Work—Dharmic religious concept of works or deeds whose divine consequences are experienced in this life or the next. | kām | work [without any religious connotations]. |

| kṣetra | Field—Abstract sense, such as a field of knowledge or activity; khāngī kṣetra → private sector. Physical sense, but of higher or special importance; raṇǎkṣetra → battlefield. | khetar | field [in agricultural sense]. |

What remains are words of foreign origin (videśī), as well as words of local origin that cannot be pegged as belonging to any of the three prior categories (deśaj). The former consists mainly of Persian, Arabic, and English, with trace elements of Portuguese and Turkish. While the phenomenon of English loanwords is relatively new, Perso-Arabic has a longer history behind it. Both English and Perso-Arabic influences are quite nationwide phenomena, in a way paralleling tatsam as a common vocabulary set or bank. What's more is how, beyond a transposition into general Indo-Aryan, the Perso-Arabic set has also been assimilated in a manner characteristic and relevant to the specific Indo-Aryan language it is being used in, bringing to mind tadbhav.

Perso-Arabic

India was ruled for many centuries by Persian-speaking Muslims, amongst the most notable being the Delhi Sultanate, and the Mughal dynasty. As a consequence Indian languages were changed greatly, with the large scale entry of Persian and its many Arabic loans into the Gujarati lexicon. One fundamental adoption was Persian's conjunction "that", ke. Also, while tatsam or Sanskrit is etymologically continuous to Gujarati, it is essentially of a differing grammar (or language), and that in comparison while Perso-Arabic is etymologically foreign, it has been in certain instances and to varying degrees grammatically indigenised. Owing to centuries of situation and the end of Persian education and power, (1) Perso-Arabic loans are quite unlikely to be thought of or known as loans, and (2) more importantly, these loans have often been Rajasthani-ized. dāvo – claim, fāydo – benefit, natījo – result, and hamlo – attack, all carry Gujarati's masculine gender marker, o. khānũ – compartment, has the neuter ũ. Aside from easy slotting with the auxiliary karnũ, a few words have made a complete transition of verbification: kabūlnũ – to admit (fault), kharīdnũ – to buy, kharǎcnũ – to spend (money), gujarnũ – to pass. The last three are definite part and parcel.

Below is a table displaying a number of these loans. Currently some of the etymologies are being referenced to an Urdu dictionary so that Gujarati's singular masculine o corresponds to Urdu ā, neuter ũ groups into ā as Urdu has no neuter gender, and Urdu's Persian z is not upheld in Rajasthani and corresponds to j or jh. In contrast to modern Persian, the pronunciation of these loans into Rajasthani and other Indo-Aryan languages, as well as that of Indian-recited Persian, seems to be in line with Persian spoken in Afghanistan and Central Asia, perhaps 500 years ago.[38]

| Nouns | Adjectives | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | n | f | |||||||||||||||||||||

| fāydo | gain, advantage, benefit | A | [39] | khānũ | compartment | P | [40] | kharīdī | purchase(s), shopping | P | [41] | tājũ | fresh | P | [42] | ||||||||

| humlo | attack | A | [43] | makān | house, building | A | [44] | śardī | common cold | P | [45] | judũ | different, separate | P | [46] | ||||||||

| dāvo | claim | A | [47] | nasīb | luck | A | [48] | bāju | side | P | [49] | najīk | near | P | [50] | ||||||||

| natījo | result | A | [51] | śaher | city | P | [52] | cījh | thing | P | [53] | kharāb | bad | A | [54] | ||||||||

| gusso | anger | P | [55] | medān | plain | P | [56] | jindgī | life | P | [57] | lāl | red | P | [58] | ||||||||

Lastly, Persian, being part of the Indo-Iranian language family as Sanskrit and Rajasthani are, met up in some instances with its cognates:[59]

| Persian | Indo-Aryan | English |

|---|---|---|

| marăd | martya | man, mortal |

| stān | sthān | place, land |

| ī | īya | (adjectival suffix) |

| band | bandh | closed, fastened |

| shamsheri | aarkshak | policeman |

Zoroastrian Persian refugees known as Parsis also speak an accordingly Persianized form of Gujarati.[60]

English

With the end of Perso-Arabic inflow, English became the current foreign source of new vocabulary. English had and continues to have a considerable influence over Indian languages. Loanwords include new innovations and concepts, first introduced directly through British colonial rule, and then streaming in on the basis of continued Anglophone dominance in the Republic of India. Besides the category of new ideas is the category of English words that already have Rajasthani counterparts which end up replaced or existed alongside. The major driving force behind this latter category has to be the continuing role of English in modern India as a language of education, prestige, and mobility. In this way, Indian speech can be sprinkled with English words and expressions, even switches to whole sentences.[61] See Hinglish, Code-switching.

In matters of sound, English alveolar consonants map as retroflexes rather than dentals. Two new characters were created in Rajasthani to represent English /æ/'s and /ɔ/'s. Levels of Rajasthani-ization in sound vary. Some words do not go far beyond this basic transpositional rule, and sound much like their English source, while others differ in ways, one of those ways being the carrying of dentals. See Indian English.

As English loanwords are a relatively new phenomenon, they adhere to English grammar, as tatsam words adhere to Sanskrit. That is not to say that the most basic changes have been underway: many English words are pluralised with Rajasthani o over English "s". Also, with Rajasthani having three genders, genderless English words must take one. Though often inexplicable, gender assignment may follow the same basis as it is expressed in Gujarati: vowel type, and the nature of word meaning.

| Loanword | English source |

|---|---|

| bâṅk | bank |

| phon | phone |

| ṭebal | table |

| bas | bus |

| rabbar | rubber |

| dôkṭar | doctor |

| rasīd | receipt |

| helo halo hālo |

hello |

| hôspiṭal aspitāl ispitāl |

hospital |

| sṭeśan ṭeśan |

railway station |

| sāykal | bicycle |

| rum | room |

| āis krīm | ice cream |

| esī | air conditioning |

| aṅkal1 | uncle |

| āṇṭī1 | aunt |

| pākīṭ | wallet |

| kavar | envelope |

| noṭ | banknote |

| skūl | school |

| ṭyuśan | tuition |

| miniṭ | minute |

| ṭikiṭ ṭikaṭ |

ticket |

| sleṭ | slate |

| hoṭal | hotel |

| pārṭī | political party |

| ṭren | train |

| kalekṭar | district collector |

| reḍīyo | radio |

- 1 These English forms are often used (prominently by NRIs) for those family friends and elders that are not actually uncles and aunts but are of the age.

Portuguese

The smaller foothold the Portuguese had in wider India had linguistic effects due to extensive trade. Rajasthani took up a number of words, while elsewhere the influence was great enough to the extent that creole languages came to be (see Portuguese India, Portuguese-based creole languages in India and Sri Lanka). Comparatively, the impact of Portuguese has been greater on coastal languages[62] and their loans tend to be closer to the Portuguese originals.[63] The source dialect of these loans imparts an earlier pronunciation of ch as an affricate instead of the current standard of [ʃ].[38]

| Rajasthani | Meaning | Portuguese |

|---|---|---|

| istrī | iron(ing) | estirar1 |

| mistrī2 | carpenter | mestre3 |

| sābu | soap | sabão |

| chābī | key | chave |

| tambāku | tobacco | tabaco |

| gobī | cabbage | couve |

| kāju | cashew | cajú |

| pāũ | bread | pão |

| baṭāko | potato | batata |

| anānas | pineapple | ananás |

| pādrī | father (in Catholicism) | padre |

| aṅgrej(ī) | English (not specifically the language) | inglês |

| nātāl | Christmas | natal |

- 1 "To stretch (out)".

- 2 Common occupational surname.

- 3 "Master".

Loans into English

1676, from Gujarati bangalo, from Hindi bangla "low, thatched house," lit. "Bengalese," used elliptically for "house in the Bengal style."[64]

1598, "name given by Europeans to hired laborers in India and China," from Hindi quli "hired servant," probably from koli, name of an aboriginal tribe or caste in Gujarat.[65]

Tank—

c.1616, "pool or lake for irrigation or drinking water," a word originally brought by the Portuguese from India, ult. from Gujarati tankh "cistern, underground reservoir for water," Marathi tanken, or tanka "reservoir of water, tank." Perhaps from Skt. tadaga-m "pond, lake pool," and reinforced in later sense of "large artificial container for liquid" (1690) by Port. tanque "reservoir," from estancar "hold back a current of water," from V.L. *stanticare (see stanch). But others say the Port. word is the source of the Indian ones.[66]

Writing system

In India, Rajasthani is written in the Devanagari script, an abugida which is written from left to right. Earlier, the Mahajani script, or Modiya, was used to write Rajasthani. The script is also called as Maru Gurjari in a few records. In Pakistan, where Rajasthani is considered a minor language,[67] a variant of the Sindhi script is used to write Rajasthani dialects.[68][69]

| Devanagari | Perso-Arabic | Latin | IPA |

|---|---|---|---|

| अ | — | a | ə |

| आ | ﺍ | ā | ɑ |

| इ | ـِ | i | ɪ |

| ई | ﺍیِ | ī | i |

| उ | ـُ | u | ʊ |

| ऊ | ﺍۇ | ū | u |

| अे | اے | e | e |

| ओ | ﺍو | o | o |

| औ | |||

| अं | — | ã | ə̃ |

| आं | ā̃ | ɑ̃ | |

| इं | ĩ | ɪ̃ | |

| ईं | ī̃ | ĩ | |

| उं | ũ | ʊ̃ | |

| ऊं | ū̃ | ũ | |

| एं | ẽ | ẽ | |

| ओं | õ | õ | |

| क | ک | k | k |

| ख | کھ | kh | kʰ |

| ग | گ | g | g |

| घ | گھ | gh | gʱ |

| च | چ | c | t͡ʃ |

| छ | چھ | ch | t͡ʃʰ |

| ज | ج | j | d͡ʒ |

| झ | جھ | jh | d͡ʒʰ |

| ट | ٹ | ṭ | ʈ |

| ठ | ٹه | ṭh | ʈʰ |

| ड | ڈ | ḍ | ɖ |

| ढ | ڈه | ḍh | ɖʰ |

| ॾ | ڏ | d̤ | ᶑ |

| ॾ़ | ڏه | d̤h | ᶑʰ |

| ण | ݨ | ṇ | ɳ |

| ण़ | ݨه | ṇh | ɳʰ |

| त | ت | t | t̪ |

| थ | تھ | th | t̪ʰ |

| द | د | d | d̪ |

| ध | ده | dh | d̪ʰ |

| न | ن | n | n |

| ऩ | نھ | nh | nʰ |

| प | پ | p | p |

| फ | پھ | ph | pʰ |

| ब | ب | b | b |

| भ | بھ | bh | bʰ |

| ॿ | ٻ | b̤ | ɓ |

| ॿ़ | ٻه | b̤h | ɓʰ |

| म | م | m | m |

| म़ | مھ | mh | mʰ |

| य | ےٜٜ | y | j |

| र | ر | r | ɾ |

| ड़ | رؕ | r̤ | ɽ |

| ढ़ | رؕه | r̤h | ɽʰ |

| ज़ | ز | z | z |

| ॼ़ | زه | zh | zʰ |

| ल | ل | l | l |

| ल़ | لھ | lh | lʰ |

| ळ | ݪ | ḷ | ɭ |

| व | v | ||

| श | ɕ | ||

| ष | ʂ | ||

| स | s | ||

| स़ | |||

| ह | ɦ | ||

| श्र | |||

| क्ष |

The letter 'ळ'(ɭ) is specially used in Rajasthani script. 'ल'(l) and 'ळ'(ɭ) have different sounds. The use of both has different meanings, like कालौ (black color) and काळौ (insane).

In Rajasthani language, there are sounds of palatal 'श'(sh) and nasal 'ष'(sh), but in Rajasthani script only dental 'स'(s) is used for them. Similarly, in Rajasthani script, there is no independent sign for 'ज्ञ'(gya), instead 'ग्य'(Gya) is written in its place. In Rajasthani script, there is no sound of the conjuncts, for example, instead of the conjunct letter 'क्ष'(ksh), 'च'(Ch), 'क'(ka) or 'ख'(kha) is written, like लखण (Lakhan) of लक्षमण (Lakshan), लिछमण (Lichhman) of लक्ष्मण (Lakshman) and राकस (Rakas) of राक्षस (Rakshas). In Rajasthani script, there is no separate symbol for the sound of 'ऋ'(Ri), instead 'रि'(Ri) is written instead of it, like रितु (Ritu) (season) instead of ऋतु (Ritu). In Rajasthani, there is no use of ligatures and ref. The whole of ref 'र्' (r) becomes 'र' (ra), for example, instead of 'धर्म' (dharm), 'धरम'(dharam), instead of 'वक्त'(vakt) (time), 'वगत'(vagat) or 'वखत'(vakhat) are written. Single quotation mark (') is also used to denote continuation sound like देख'र(dekha'r) हरे'क (hare'k)(every) etc. अे (e) and अै (ai) are written instead of ए(e) and ऐ (ai) like 'अेक'(ek)(one) in place of 'एक'(ek).

Writing styles

Old literary Rajasthani had two types of writing styles.

Dingal

A literary style of writing prose and poetry in Maru-Bhasa language. It is presented same in written and spoken form. Kushallabh's 'Pingali Shiromani', Giridhar Charan's 'Sagat Singh Raso' dedicated to Maharana Pratap's younger brother Shakti Singh has been written in Dingal language. It was also used in composition of Suryamal Misharan and Baankidas.[70] Dingal is literary genre of Charans and is written as couplets, songs and poems.

Pingal

It was used for writing poem only by Bhats and Ravs. It is an amalgamation of Brij Bhasha and Rajasthani languages.[71]

Literature

Prominent linguists

Linguists and their work and year: [Note: Works concerned only with linguistics, not with literature]

- Ram Karan Asopa: Dingal Sabdkosh (Dingal Dictionary) :Rajasthani and Marwari, 1890–1920

- George Macalister: Dhundhari and Shekhawati, 1892

- L. P. Tessitori: Rajasthani and Marwari, 1914–16

- George Abraham Grierson: Almost all the dialects of Rajasthani, 1920

- Kan Singh Parihar: English, Sanskrit, Hindi, Marwari, Rajasthani, 1940

- Saubhagya Singh Shekhawat Rajasthani, Rajasthani Shabd-Kosh part I Sanshodhan Parivardhan, 1945–present

- Suniti Kumar Chatterjee: Rajasthani, 1948–49

- Sita Ram Lalas: Rajasthani language, 1950–1970

- W.S. Allen: Harauti and Rajasthani, 1955–60

- Narottam Das Swami: Rajasthani and Marwari, 1960

- K. C. Agrawal: Shekhawati, 1964

- John D. Smith: Rajasthani, 1970–present

- J. C. Sharma: Gade lohar, Bagri or Bhili, Gojri, 1970–present

- Kali Charan Bahl: Rajasthani, 1971–1989

- Christopher Shackle: Bagri and Saraiki, 1976

- David Magier: Marwari, 1983

- Peter E. Hook: Rajasthani and Marwari, 1986

- Lakhan Gusain: all the dialects of Rajasthani, 1990–present

- Liudmila Khokhlova: Rajasthani and Marwari, 1990–present

- Anvita Abbi: Bagri, 1993

- Maxwell P Philips: Bhili, 2000–present.

- Gopal Parihar: Bagri, 2004–present

- Amitabh V. Dwivedi: Hadoti, 2015

- Gulab Chand: Hadoti, 2018

Sample text

The following is a sample text in High Hindi, of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (by the United Nations):

- Rajasthani in Devanagari Script

- अनुच्छेद १(एक):सगळा मिनख आजाद अर मरयादा अर अधिकारां मायं बरोबरी ले'र जलम लेवै। वै तरक अर बिवेक सु भरां होवै अर वानै भाईचारे री भावना सु एक बिजा सारुं काम करणौ चाहिजै।

- Hindi in Devanagari Script

- अनुच्छेद १(एक): सभी मनुष्य जन्म से स्वतन्त्र तथा मर्यादा और अधिकारों में समान होते हैं। वे तर्क और विवेक से सम्पन्न हैं तथा उन्हें भ्रातृत्व की भावना से परस्पर के प्रति कार्य करना चाहिए।

- Transliteration (ISO)

- anuccheda 1(eka):sagalā minakha jinama su sutaṁtara ara marayāda ara adhikārāṁ māyaṁ barobara hove। be tarka ara biveka su sampanna hai ara uṇone bhāyapana rī bhāvanā su eka bijā sāruṁ kāma karaṇo cāhijai

- Gloss (word-to-word)

- Article 1 (one) – All humans birth from independent and dignity and rights in equal are. They logic and conscience from endowed are and they fraternity in the spirit of each other towards work should.

- Translation (grammatical)

- Article 1 – All humans are born independent and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with logic and conscience and they should work towards each other in the spirit of fraternity.

Media

First newspaper published in Rajasthani was Rajputana Gazette published from Ajmer in 1885. First film made in Rajasthani was Nazrana in 1942. Stage app is first OTT platform in Rajasthani and Haryanvi and Gangaur TV is the first TV channel in Rajasthani.[72][73] All India Radio air and publish news in Rajasthani language.[74]

Language movement

A movement is ongoing in Rajasthan since independence of India to include Rajasthani language in the 8th schedule of the Indian constitution and making it the official language of the state of Rajasthan. In recent years the movement is getting rooted among the youths.

Challenges and Preservation Efforts

The Rajasthani language faces several issues, including:

- 1. Lack of Official Recognition

Despite being widely spoken, Rajasthani lacks official status in India. It is often classified under Hindi in government documents and the census, which undermines its distinct identity. This also means it is not listed in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, depriving it of the support and promotion that other scheduled languages receive.

- 2. Standardization Challenges

Rajasthani comprises numerous dialects, such as Marwari, Mewari, Shekhawati, and Hadoti, among others. The lack of a standardized form makes it difficult to unify and promote the language effectively and can lead to fragmentation in efforts to preserve and promote the language.

- 3. Educational Neglect

Rajasthani is not widely taught in schools. The educational system predominantly uses Hindi or English, leading to a decline in the younger generation's proficiency in their native tongue. This lack of formal education and institutional support further contributes to the erosion of the language.

- 4. Media Representation

There is limited representation of Rajasthani in mainstream media, including television, radio, and print. This lack of visibility reduces the language's presence in everyday life and its prestige among speakers.

- 5. Literary Development

Although Rajasthani has a rich literary tradition, contemporary literary output and publishing are limited. This affects the development and modernization of the language and hinders efforts to preserve its cultural heritage.

- 6. Economic and Social Pressures

Urbanization and migration often lead speakers to prioritize learning Hindi or English for better economic and social opportunities. This shift can lead to a decrease in the use of Rajasthani in daily life and a decline in language transmission to future generations.

- 7. Linguistic Erosion

As younger generations shift to Hindi or English, the transmission of Rajasthani to future generations is at risk, potentially leading to language erosion. In many families, younger generations are not learning Rajasthani at home, often due to the preference for more dominant languages.

Addressing these issues requires concerted efforts from the government, educational institutions, and cultural organizations to promote and preserve the Rajasthani language. Efforts to improve official recognition, standardize the language, enhance its presence in education and media, and support its literary and cultural development are crucial for its preservation and promotion.

Notes

- ^ 39 million in Rajasthan and 7 million in Madhya Pradesh

References

- ^ a b Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2023). Ethnologue: Languages of the World (26th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International.

- ^ Ernst Kausen, 2006. Die Klassifikation der indogermanischen Sprachen (Microsoft Word, 133 KB)

- ^ Strasser, Susan (16 December 2013). Commodifying Everything: Relationships of the Market. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-70685-1.

- ^ Kudaisya, Medha M.; Ng, Chin-Keong (2009). Chinese and Indian Business: Historical Antecedents. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-17279-1.

- ^ Central Bureau of Statistics (2014). Population monograph of Nepal (PDF) (Report). Vol. II. Government of Nepal.

- ^ Masica, Colin (1991), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- ^ a b c 2011 Census data censusindia.gov.in [dead link]

- ^ "Ethnologue.com: Ethnologue report for Rajasthani". Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ "Pakistan & Afghanistan – Carte linguistique / Linguistic map".

- ^ Gold, Ann Grodzins. A Carnival of Parting: The Tales of King Bharthari and King Gopi Chand as Sung and Told by Madhu Natisar Nath of Ghatiyali, Rajasthan. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3g500573/

- ^ "pg no 293,296".

- ^ "Browse by Language Family". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Angika". Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ "..:: Welcome to Sahitya Akademi – About us ::." sahitya-akademi.gov.in. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ "awards & fellowships-Akademi Awards". 28 August 2009. Archived from the original on 28 August 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ R. S. Gupta, Anvita Abbi, Kailash S. Aggarwal (1995). Language and the State Perspectives on the Eighth Schedule (1995 ed.). University of Michigan: Creative Books. pp. 92, 93, 94. ISBN 9788186318201.

{cite book}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Press Trust of India, "Sit-in for constitutional recognition of Rajasthani planned", 4 May 2015, The Economic Times. Accessed 22 April 2016.

- ^ Press Trust of India, "Vasundhara Raje flags off ‘Rajasthani language rath yatra’", 26 July 2015, The Economic Times. Accessed 22 April 2016

- ^ "Vasundhara Raje flags off 'Rajasthani language rath yatra'". The Economic Times. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ "Rajasthani language introduced in state's open school system". India Today. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ Bureau (18 March 2023). "Exercise begins for declaring Rajasthani second official language". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

{cite news}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Bureau (11 January 2023). "Demand gains momentum for making Rajasthani official language". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

{cite news}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Panel to see if Rajasthani can be 2nd official language of Rajasthan". The Times of India. 17 March 2023. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ "Facts about Gujarat".

- ^ Smith, John D (29 January 1992). "EPIC RAJASTHANI". Indo-Iranian Journal. 35 (2/3): 251–269. doi:10.1163/000000092790083642. JSTOR 24659527 – via JOSTOR.

- ^ Gusain 2000b

- ^ Gusain 2003

- ^ Dixon 1994.

- ^ "?" (PDF). Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ Snell, R. (2000) Teach Yourself Beginner's Hindi Script. Hodder & Stoughton. pp. 83–86.

- ^ Turner (1966), p. 44. Entry 992..

- ^ Turner (1966), p. 203. Entry 3856..

- ^ Turner (1966), p. 30. Entry 684..

- ^ Turner (1966), p. 502. Entry 8947..

- ^ Turner (1966), p. 706. Entry 12193..

- ^ Turner (1966), p. 762. Entry 13173..

- ^ Turner (1966), p. 766. Entry 13276..

- ^ a b Masica (1991), p. 75.

- ^ Platts (1884), p. 776.

- ^ Platts (1884), p. 486.

- ^ Platts (1884), p. 489.

- ^ Platts (1884), p. 305.

- ^ Tisdall (1892), p. 168.

- ^ Platts (1884), p. 1057.

- ^ Platts (1884), p. 653.

- ^ Tisdall (1892), p. 170.

- ^ Platts (1884), p. 519.

- ^ Platts (1884), p. 1142.

- ^ Tisdall (1892), p. 160.

- ^ Tisdall (1892), p. 177.

- ^ Platts (1884), p. 1123.

- ^ Tisdall (1892), p. 184.

- ^ Platts (1884), p. 471.

- ^ Tisdall (1892), p. 172.

- ^ Platts (1884), p. 771.

- ^ Tisdall (1892), p. 175.

- ^ Tisdall (1892), p. 169.

- ^ Platts (1884), p. 947.

- ^ Masica (1991), p. 71.

- ^ Tisdall (1892), p. 15.

- ^ Masica (1991), pp. 49–50.

- ^ Masica (1991), p. 49.

- ^ Masica (1991), p. 73.

- ^ Bungalow. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Coolie. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Tank. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ "Language policy, multilingualism and language vitality in Pakistan" (PDF). Quaid-i-Azam University. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "Goaria". Ethnologue. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ "Dhatki". Ethnologue. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ^ Ayyappappanikkar (1997). Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections. Sahitya Akademi. p. 453. ISBN 978-81-260-0365-5.

- ^ Mukherjee, Sujit (1998). A Dictionary of Indian Literature: Beginnings-1850. Orient Blackswan. p. 289. ISBN 978-81-250-1453-9.

- ^ "Rajasthani GEC channel 'Gangaur Television' makes its debut – Exchange4media". Indian Advertising Media & Marketing News – exchange4media. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Jha, Lata (27 November 2023). "Neeraj Chopra invests in regional OTT app Stage". mint. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "AIR News Rajasthani".

Sources

- Platts, John T. (John Thompson) (1884), A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English, London: W.H. Allen & Co.

- Tisdall, W.S. (1892), A Simplified Grammar of the Gujarati Language.

- Turner, Ralph Lilley (1966), A Comparative Dictionary of the Indo-Aryan Languages, London: Oxford University Press.